Today, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) released model rules for the global minimum tax (also known as Pillar 2). These rules are designed to apply to multinational companies with more than €750 million in total global revenues and place a minimum effective tax rate of 15 percent on those company’s profits.

In the coming days, countries will be considering how to incorporate these rules into their national taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. codes. The rules are complex, and some countries may opt to put them in place on top of preexisting rules for taxing multinational companies. However, countries should also consider ways to reform their existing rules in response to the minimum tax.

The global minimum tax rules do not require any changes in domestic tax law. The approach is voluntary, but if enough countries do enact the rules, then even countries that do not adopt them should evaluate their tax policies with an eye toward simplification, revenue-neutral reforms, and policies that support investment which would not be eroded by the minimum tax.

Many jurisdictions around the world offer tax preferences or structure their tax rules in such a way that allow companies to be taxed at rates below the 15 percent rate envisioned by the minimum tax.

The global minimum tax can create problems for those policies, however. For example, let’s say a large multinational company headquartered in Country A makes an investment in Country B which is eligible for a 10-year corporate tax holiday. Even though the profits from the investment will not be taxed by Country B, the global minimum tax would allow Country A to apply the minimum rate of 15 percent to those profits.

Country B may choose to change its tax holiday policy to tax those profits locally rather than allowing the tax revenue to go to Country A. If Country B applies a high corporate tax rate to companies that are not eligible for a tax holiday, the additional revenue from shutting down the preferential policy could support a more general tax reform (broadening the base and lowering the rates, as the mantra goes).

Not all tax policies will follow such a straightforward analysis, however, and the model rules are only helpful in assessing policies to the extent that they result in effective tax rates below 15 percent for large multinational companies.

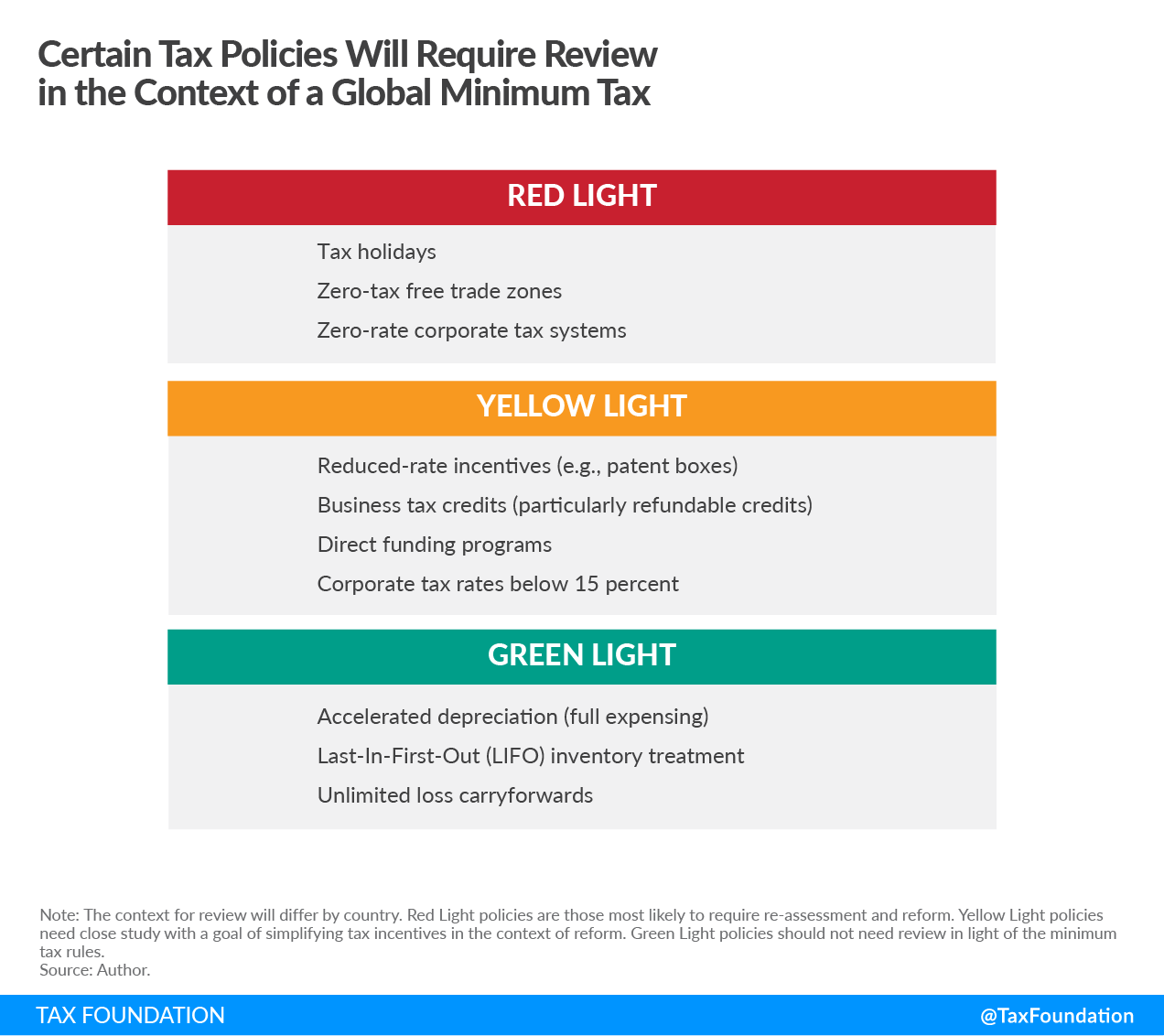

With the risk of oversimplifying, I have developed a rough categorization of the policies that countries will most likely choose to change in the context of the minimum tax rules. Policies facing a Red Light are primarily those that provide a zero effective tax rate. Yellow Light policies provide reduced effective tax rates below 15 percent but not zero. Green Light policies are those that reduce the cost of investment while not triggering the minimum tax unless the general corporate tax rate is very low.

Though the list below is not comprehensive, policymakers can use this framework to prioritize the type of evaluations which will be necessary to determine the direction tax policy should take when the minimum tax rules are in place. Once that evaluation is complete, policies that generally promote investment in fixed assets and local hiring should be prioritized because they will align with the areas where the minimum tax provides meaningful carveouts.

Even in the context of the global minimum tax, countries can and should pursue principled, competitive, and pro-growth policies that provide sufficient revenue while minimizing economic distortions.

Red Light

- Tax holidays

- Zero-tax free trade zones

- Zero-rate corporate tax systems

Countries that have rules that provide a zero tax rate on business profits either through tax holidays, free trade zones, or because there is no corporate tax face a clear choice in the context of the global minimum tax.

As the example above described, countries can choose to change their policies and collect revenue themselves (potentially in the context of a broader reform) or they can allow a foreign jurisdiction to collect the revenue associated with the 15 percent minimum effective rate.

The choices may be easier for jurisdictions that have a general corporate tax that applies outside of tax holidays or certain zones than for countries that do not operate a corporate tax at all.

The latter will need to assess whether the additional revenue will be worth the administrative costs of establishing new rules and systems for collecting a tax that they had previously chosen to not have as part of their laws. In our recent report, we noted that 15 jurisdictions around the world do not have a corporate income tax.

Yellow Light

- Reduced-rate incentives (e.g., patent boxes)

- Business tax credits (particularly refundable credits)

- Direct funding programs

- Corporate tax rates below 15 percent

This category of policies will likely prove more challenging for governments to assess in view of the global minimum tax.

If a country has a patent box rate of 10 percent (and the patent boxA patent box—also referred to as intellectual property (IP) regime—taxes business income earned from IP at a rate below the statutory corporate income tax rate, aiming to encourage local research and development. Many patent boxes around the world have undergone substantial reforms due to profit shifting concerns. complies with OECD guidelines), it might be assumed that the country should just raise the patent box rate to 15 percent or repeal it altogether. However, if the country has a general corporate tax rate of 25 percent, a company could have some of its profits subject to the 10 percent patent box rate and the rest subject to the general 25 percent rate. Even in that case, one option which should be considered is to repeal the patent box and reduce the corporate tax rate for an overall revenue-neutral reform.

Nineteen OECD countries have a policy that provides either an exemption or lower rate for income from certain patented technology, and in each case the applicable rate is lower than 15 percent. However, Italy has already opted to remove its patent box in favor of new deductions for research and development costs.

Under the global minimum tax model rules, refundable tax credits and direct funding will increase the income of a company and lower the measured effective tax rate. If a company benefiting from these policies is in a jurisdiction with a low enough corporate tax rate, the size of the credits and funding have the potential to push a company below the overall 15 percent effective tax rate threshold.

There will also be a need to assess general business tax credits since a country providing tax credits for certain activities may find that the companies receiving those credits are simply paying additional tax elsewhere.

Countries that have tax rates below 15 percent should consider whether to put the new rules in place just for the large companies targeted by the minimum tax or raise the general corporate tax rate. In a recent study, we highlighted 20 jurisdictions that operate a corporate tax rate below 15 percent (but greater than zero).

Ireland is expected to adopt the minimum tax rules for large multinationals while leaving its 12.5 percent rate in place for all other businesses.

The Yellow Light policies will be tricky to evaluate because they will depend on many factors, including the overall corporate tax rate, the number of companies benefiting from the preferences, and the ambition of lawmakers to undertake a general reform that could eliminate or trim multiple preferential policies with a goal of improving the tax system overall.

Green Light

- Accelerated depreciationDepreciation is a measurement of the “useful life” of a business asset, such as machinery or a factory, to determine the multiyear period over which the cost of that asset can be deducted from taxable income. Instead of allowing businesses to deduct the cost of investments immediately (i.e., full expensing), depreciation requires deductions to be taken over time, reducing their value and discouraging investment. (full expensingFull expensing allows businesses to immediately deduct the full cost of certain investments in new or improved technology, equipment, or buildings. It alleviates a bias in the tax code and incentivizes companies to invest more, which, in the long run, raises worker productivity, boosts wages, and creates more jobs. )

- Last-In-First-Out (LIFO) inventory treatment

- Unlimited loss carryforwards

The global minimum tax rules do not mean that all business tax policies need to be rethought. In fact, the way the rules calculate the minimum tax rate matters a great deal. The rules use the concepts of deferred tax assets and loss carryforwards that allow some important features of good tax systems to be outside the zone of policies that might need to be reconsidered.

These policies include accelerated depreciation (or full expensing) of assets like the rules that are currently in place in the U.S. and Canada. Super-deductions for business investment as in the UK would also be spared. Many countries use capital cost allowances to spur investment during economic downturns. The policy response to the pandemic has seen eight OECD countries adopt accelerated depreciation in certain circumstances.

Last-In-First-Out (LIFO) inventory deductions allow companies to deduct the cost of inventory at the price of the most recently acquired items and therefore help mitigate the impacts of volatile prices or inflationInflation is when the general price of goods and services increases across the economy, reducing the purchasing power of a currency and the value of certain assets. The same paycheck covers less goods, services, and bills. It is sometimes referred to as a “hidden tax,” as it leaves taxpayers less well-off due to higher costs and “bracket creep,” while increasing the government’s spending power. . This lowers the tax cost of acquiring inventory. Fourteen OECD countries allow businesses to use LIFO for tax purposes.

Finally, policies that allow companies to carry their losses forward for an unlimited time would not need to be reevaluated. The model rules specifically allow loss carryforwards. This allows the tax rules to minimize the likelihood that a business will get caught by the minimum tax rules simply because it is in the start-up phase with significant up-front costs. As with capital allowances, many countries loosened their loss deduction policies in response to the pandemic.