Yesterday, we released a report that looks at the statewide taxation of vapor products (also known as electronic cigarettes). As we point out, the sale of vapor products grew by 23 percent in 2014, and some project that vapor products will surpass traditional cigarettes in consumption over the next decade. This leaves policymakers with the challenge of determining exactly how or whether these emerging products should be taxed.

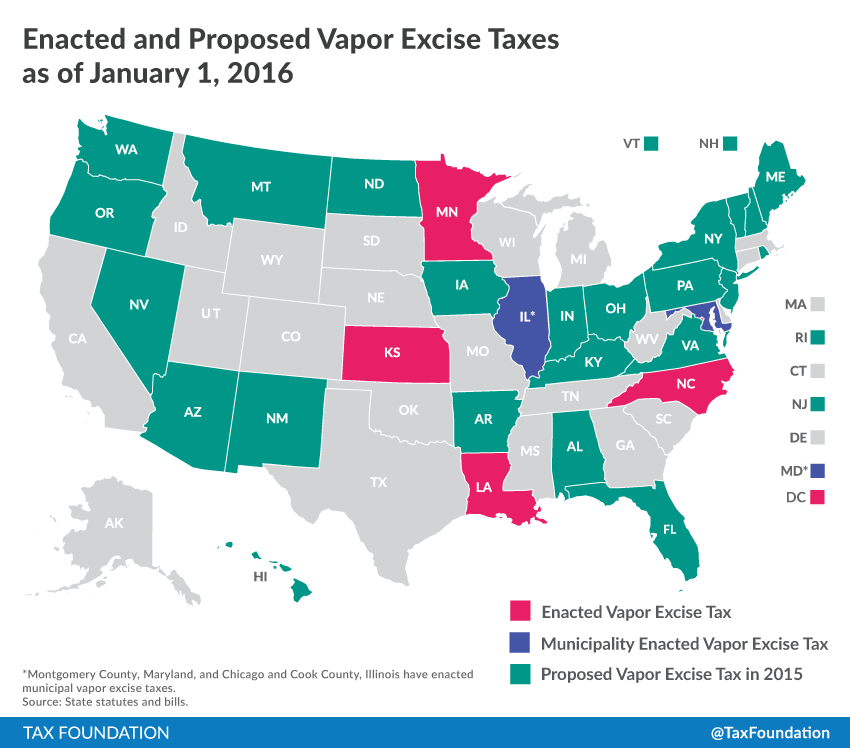

In the 2015 legislative session, at least 25 states and the District of Columbia considered legislation to taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. vapor products, either as part of a budget proposal or as a stand-alone bill. Ultimately, Louisiana, Kansas, and the District of Columbia enacted such legislation, bringing the total number of states taxing vapor products to five. Additionally, Montgomery County, Maryland, and Cook County and the City of Chicago in Illinois enacted vapor taxes in 2015.

Minnesota and North Carolina began taxing vapor products in 2012 and 2014, respectively. Each of these enacted levies varies in structure and were put in place under different circumstances.

Minnesota was the first state to begin taxing vapor products. On October 22, 2012, the state’s Department of Revenue issued a revenue notice stating that electronic cigarettes, as a “product containing, made, or derived from tobacco” and intended for consumption, fell under the definition of “other tobacco products,” a tax category that in many states includes pipe tobacco, chewing tobacco, and snuff. As a result, they are now taxed at the rate of 95 percent of their wholesale price. In addition to being the first state to tax vapor products, Minnesota remains the only state to do so administratively rather than legislatively.

North Carolina, the second state to tax vapor products, took a different approach. In 2014, the state legislature enacted legislation taxing vapor products at a rate of 5 cents per milliliter of nicotine fluid.

In the 2015 session, Kansas and Louisiana followed suit, adopting variations on the North Carolina approach of taxing by volume. Both states were prompted to impose vapor taxes to help close budget shortfalls; Kansas faced a deficit of nearly $600 million, while Louisiana stared down a $1.6 billion shortfall.

Vapor products are sufficiently new that states are just beginning to grapple with questions of if, and how, to tax them. Their apparent similarity to traditional cigarettes, despite significant areas of divergence, has complicated this debate.

But vapor products and traditional cigarettes work and are measured in fundamentally different ways, and as a result should not be taxed in the same way. Additionally, research demonstrates that vapor products are significantly less harmful than traditional cigarettes, and have potential to serve as a means of tobacco harm reduction.

A sound approach to the taxation of vapor products would avoid discriminating between disposable and rechargeable vapor products; it would avoid extending punitive tax rates from traditional cigarettes to vapor products, and would not hinder consumer opportunities for the use of vapor products as a method of smoking cessation. For more policy insight on vapor products, read our whole report here.

Share this article