When Applied Materials announced it was moving to the Netherlands a couple weeks ago, it was merely the latest in a long line of U.S. corporations fleeing the developed world’s most burdensome corporate tax. The New York Times notes some of the recent corporate moves:

Reincorporating in low-taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. havens like Bermuda, the Cayman Islands or Ireland — known as “inversions” — has been going on for decades. But as regulation has made the process more onerous over the years, companies can no longer simply open a new office abroad or move to a country where they already do substantial business.

Instead, most inversions today are achieved through multibillion-dollar cross-border mergers and acquisitions. Robert Willens, a corporate tax adviser, estimates there have been about 50 inversions over all. Of those, 20 occurred in the last year and a half, and most of those were done through mergers.

When Applied Materials announced its deal for Tokyo Electron, it said that its effective tax rate would drop to 17 percent from 22 percent as a result. For a company that had nearly $2 billion in profit in 2011, that amounts to savings of about $100 million a year.

Last year, the Eaton Corporation, a power management company from Cleveland, acquired Cooper Industries, based in Ireland, for $13 billion, and reincorporated there. The company expects to save $160 million a year as a result of the move.

In July, Omnicom, the large New York advertising group, agreed to merge with Publicis Groupe, its French rival, in a $35 billion deal. The new company will be based in the Netherlands, resulting in savings of about $80 million a year.

Also in July, Perrigo, a pharmaceutical company from Allegan, Mich., said it would acquire Elan, an Irish drug company, for $6.7 billion. Perrigo will also reincorporate in Ireland, bringing its effective tax rate to 17 percent from 30 percent, and saving the company an estimated $150 million a year, much of it in taxes.

Ireland’s 12.5 percent corporate tax rate is a big draw for some companies. Earlier in the year, Actavis, based in Parsippany, N.J., bought Warner Chilcott, a drug maker with headquarters in Dublin, and said it would reincorporate in Ireland, leading to an estimated $150 million in savings over two years.

Some other recent corporate inversions include Aon, which moved from Chicago to London in 2012, and Ensco PLC, which moved from Dallas to London in 2009. In addition to Ensco PLC, a slew of oil and gas companies moved abroad over the last 15 years, including Nabors Industries, Halliburton, Foster Wheeler, Noble Corporation, Transocean, Rowan Companies, and Weatherfield International.

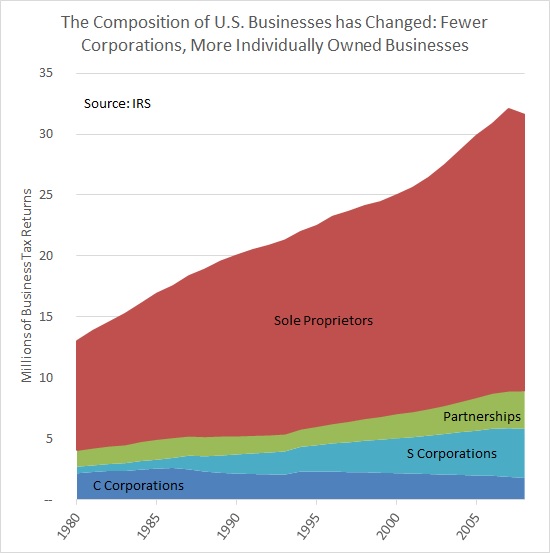

If not moving abroad, many U.S. businesses have been moving to the individual tax code, where they are taxed once on profits that are passed-through to owners, rather than twice through the corporate tax and shareholder taxes. The end result is there are now fewer corporations than at any time since the 1970s. The chart below shows standard C corporations peaked in 1986 at 2.6 million, and declined to 1.8 million as of 2008, according to the IRS. Preliminary IRS data indicates the number of C corporations dropped further to 1.6 million as of 2010. The trend shows no sign of slowing down.

It calls into question the notion of “revenue-neutral” corporate tax reform. How can we expect fewer and fewer corporations to generate the same amount of tax revenue? Shouldn’t we be more concerned about the decline of the corporate sector, and the decline of corporate investment?

Follow William McBride on Twitter

Share this article