Don’t expect data centers to blossom in the plains of Kansas: a new data center’s effective taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. rate in the state is 21 times what would be paid by a new manufacturer with similar profits. In the median state, that data center would face only one-quarter the tax burden it does in Kansas. Meanwhile, newly-established manufacturers—eligible for a host of tax incentives—get a remarkably good deal in Kansas, with effective tax rates of about 3 percent, while more mature firms, once the incentives run out, face the burdens seven times (labor-intensive manufacturers) to eight times (capital-intensive manufacturers) higher, worst in the nation.

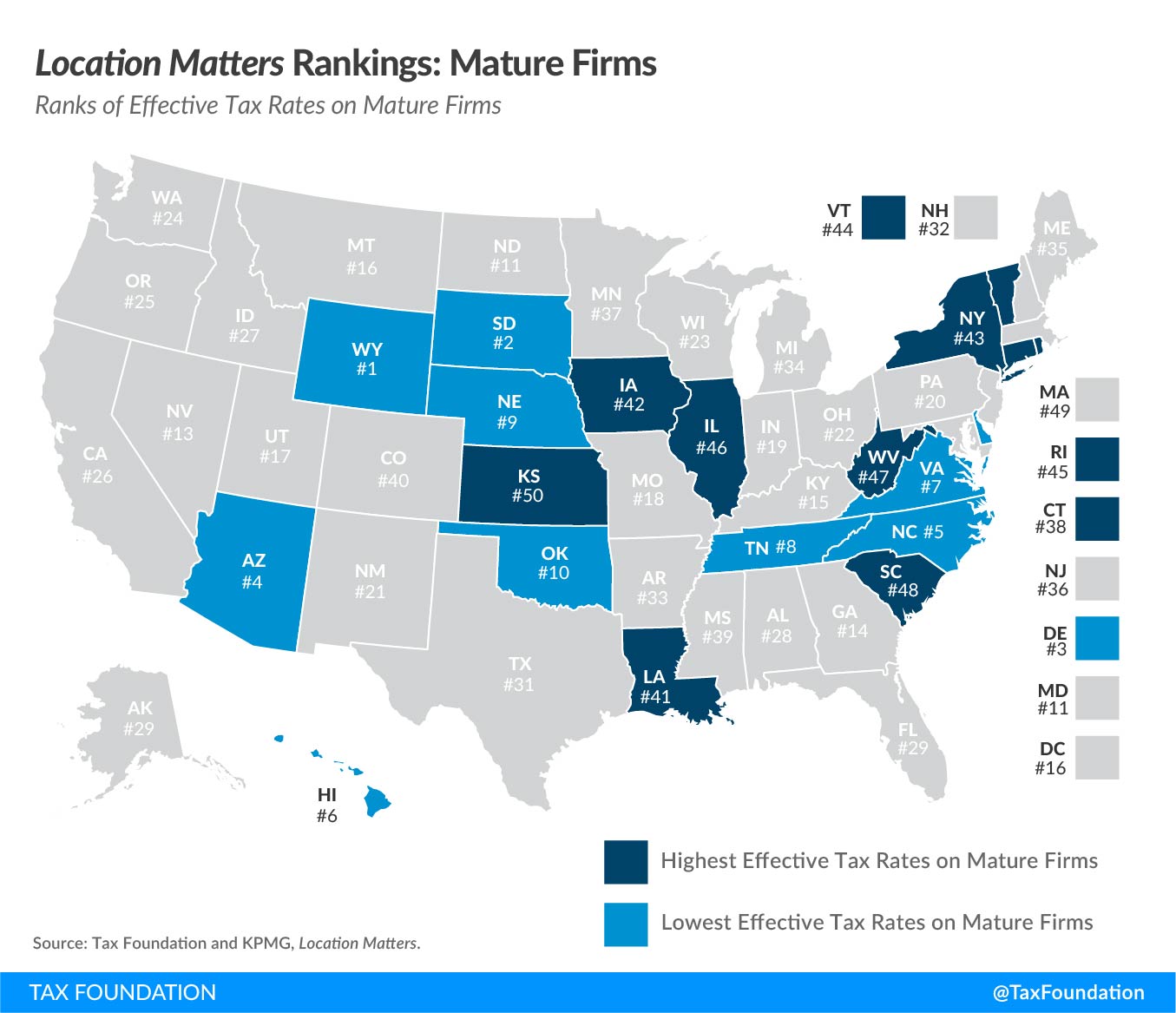

Kansas represents an extreme example of a broader phenomenon, one illustrated state-by-state with the third edition of our Location Matters: The Tax Costs of Doing Business, released today. Location Matters takes eight model firms—corporate headquarters, manufacturers, technology centers, data centers, and more—and runs their taxes in all 50 states. In fact, we do it twice: once for new firms, eligible for many tax incentives, and again as mature firms, once many of those incentives have run out. The story that emerges is a complex one, but all the more important for it.

Location Matters is not a publication with a single narrative. It is an account of tax complexity and the ways that tax structure affect competitiveness. For policymakers, it represents an opportunity to explore the seemingly more arcane tax provisions that can have a significant impact on business tax burdens, and to discover how their tax code—often completely by accident—picks winners and losers.

The book is available in PDF format, and state- and firm-specific results can be browsed in our interactive edition. Here are a few observations that emerge from the study:

- Tax structure and tax bases matter as much as, or even more than, tax rates. If the sales tax base includes business inputs, for instance, or the property tax base includes machinery, equipment, and inventory, or the corporate income tax is magnified by service sourcing rules which increase in-state taxation, tax burdens can be much higher than statutory tax rates alone would indicate. While many states with low tax rates do well in Location Matters—North Carolina, with its 2.5 percent corporate income taxA corporate income tax (CIT) is levied by federal and state governments on business profits. Many companies are not subject to the CIT because they are taxed as pass-through businesses, with income reportable under the individual income tax. rate and top five ranking for both new and mature firms is a clear example—neighboring South Carolina performs dreadfully (48th for mature firms) due to exceedingly high business property taxA property tax is primarily levied on immovable property like land and buildings, as well as on tangible personal property that is movable, like vehicles and equipment. Property taxes are the single largest source of state and local revenue in the U.S. and help fund schools, roads, police, and other services. burdens and a poor structure that overtaxes business activity.

- Traditional corporate income taxes are only a small fraction of companies’ overall tax burden. Although the corporate income tax is often considered the “business tax,” it can be dwarfed, for many operations, by other taxes, especially property taxes (on real, tangible, and even intangible property) and sales taxes (which often fall on intermediate business transactions). For mature research and development (R&D) facilities, for instance, corporate income and similar business-specific taxes only accounted for 11 percent of tax liability overall. Income tax incentives for their new counterparts, meanwhile, are so intensive that in aggregate, new R&D firms have negative corporate income tax liability while still having meaningful overall tax burdens in most states.

- Tax burdens are nonneutral both within and across firms. Every business’s exposure to the tax code is unique. Even if two firms post identical profits, many factors contribute to the calculation of their tax bills: their labor costs, the value of their real and tangible property, whether their inputs are subject to sales taxA sales tax is levied on retail sales of goods and services and, ideally, should apply to all final consumption with few exemptions. Many governments exempt goods like groceries; base broadening, such as including groceries, could keep rates lower. A sales tax should exempt business-to-business transactions which, when taxed, cause tax pyramiding. , apportionment, service sourcing, the availability of economic development incentives, and so much more. That’s how a mature data center can face a 1 percent effective tax rate in Nebraska but a 21 percent rate in neighboring Kansas, and how Nebraska—which barely taxes data centers—can hit a new distribution center with nearly a 44 percent effective tax rate on its in-state activity. Nonneutrality shows up across states within a given firm type and within states across firm types (or across new and mature firms).

- Incentives for new firms come at a cost. Many states roll out the red carpet to attract new businesses, but that often means neglecting their existing firms, saddling them with high tax burdens. All the incentives in the world, moreover, may not be enough to attract a firm with long time horizons if their tax burden will be anomalously high once the incentives run out. In Ohio, a distribution center pays two and a half times as much once the incentives run out, even though a new firm is engaging in more taxable activity (purchasing potentially taxable machinery and equipment, and with its tangible property at its lowest levels of depreciationDepreciation is a measurement of the “useful life” of a business asset, such as machinery or a factory, to determine the multiyear period over which the cost of that asset can be deducted from taxable income. Instead of allowing businesses to deduct the cost of investments immediately (i.e., full expensing), depreciation requires deductions to be taken over time, reducing their value and discouraging investment. ).

In the coming weeks, we plan to use Location Matters as a jumping-off point to explore each of these observations in greater depth. For now, we invite you to explore our new study and see how your state compares.

Launch Locations Matters Interactive Web Tool

Share this article