One of the most important provisions in the new House GOP tax plan is the disallowance of the business deduction for net interest expense. While this is not the sort of taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. provision that most individuals handle on a day-to-day basis, it is important for the way businesses are run and financed, and worthy of consideration.

The plan explains the provision here:

Under this Blueprint, job creators will be allowed to deduct interest expense against any interest income, but no current deduction will be allowed for net interest expense. Any net interest expense may be carried forward indefinitely and allowed as a deduction against net interest income in future years.

This post is intended to explain briefly why interest was deductible before, and why lawmakers are now rethinking that policy.

The basic idea is that if interest received is “income” then interest payments are a kind of anti-income, or an expense that should be deductible. There’s a variety of places where the tax code does this; for example, in the treatment of alimony payments. If you taxed alimony income and didn’t deduct alimony payments, then the same unit of salary or wage income would be taxed two times.

The same is true in our treatment of business-to-business payments. If Netflix pays Disney some money for the rights to some movies, then Netflix gets to deduct that money, and it’s counted as income for Disney. So naturally, if Netflix has a loan, its payments to the lender should be deductible expenses, and the lender should pay taxes, right?

Maybe not. Here’s why the House GOP plan is beginning to consider the issue differently:

A system that adds a deduction and requires income reporting of that deductible expense is inevitably going to allow more creative tax planning strategies than one that doesn’t. In the case of alimony income, for example, people likely overreport their deductions and underreport their income. Corporate tax planning is a bit more complicated than this, but it develops a similar issue, where the hole in the tax baseThe tax base is the total amount of income, property, assets, consumption, transactions, or other economic activity subject to taxation by a tax authority. A narrow tax base is non-neutral and inefficient. A broad tax base reduces tax administration costs and allows more revenue to be raised at lower rates. created by the interest deduction ends up being far larger than the taxes on interest income coming in.

A key thing to remember here is that not all lenders actually pay taxes on interest income in the U.S., because some lenders aren’t subject to U.S. taxes on interest income. An example of this might be a large university endowment, or a large foreign fund.

This is especially important because the U.S. has an unusually high corporate income taxA corporate income tax (CIT) is levied by federal and state governments on business profits. Many companies are not subject to the CIT because they are taxed as pass-through businesses, with income reportable under the individual income tax. rate. One common strategy for U.S. businesses is to use leverage (borrowing) substantially, in order to have a lot of deductible interest payments to count against its income. Then, you try to make those interest payments to someone who would have a lower marginal tax rateThe marginal tax rate is the amount of additional tax paid for every additional dollar earned as income. The average tax rate is the total tax paid divided by total income earned. A 10 percent marginal tax rate means that 10 cents of every next dollar earned would be taken as tax. , which saves money overall on the scheme. This is a means for profit shifting, the phenomenon where corporate income is reported less in jurisdictions with higher tax rates.

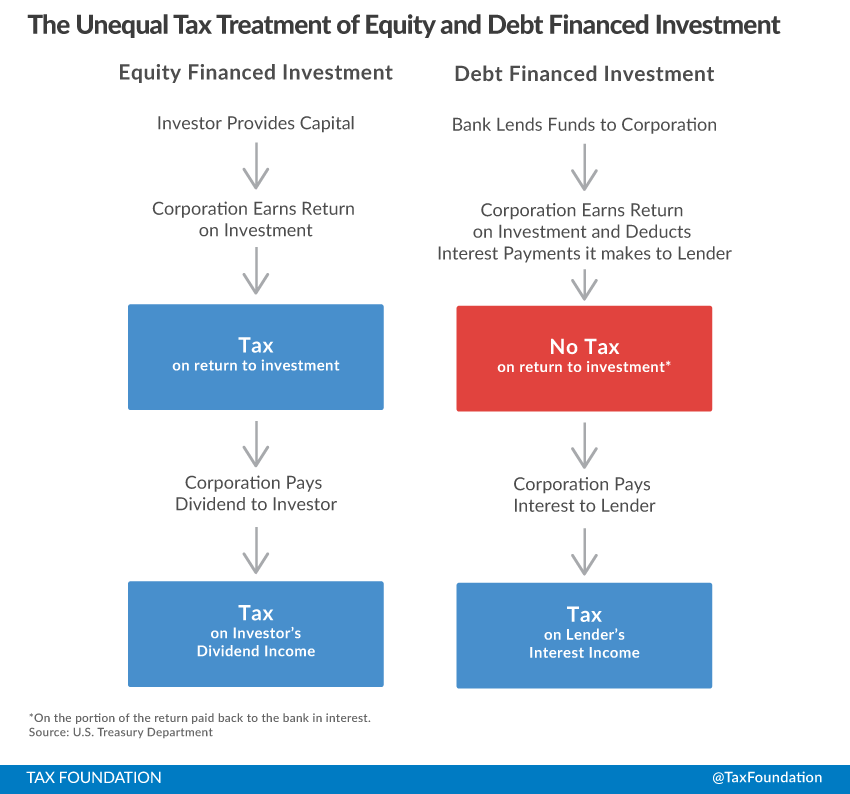

Another reason to consider this change is that dividend payments, a different kind of corporate financing, are not deductible. Economists call this the bias of debt finance over equity finance. As a recent Tax Foundation report describes it:

When a corporation wants to fund a new project it can either finance it through equity (issue of new stock) or it can borrow money. There are many non-tax reasons that a corporation would choose one funding mechanism over another, but the current tax code treats debt financing more favorably than equity financing. Specifically, there are two layers of taxation on equity financing and only one layer of taxation on debt financing.

Suppose a corporation decides to raise money to purchase a machine by issuing new stock. When this investment earns a profit the corporation needs to pay the corporate income tax. It then needs to compensate the original investors, so the corporation distributes the after-tax earnings as dividends. The investors then need to pay tax on the dividends they receive from the corporation. This equity-financed project nets two layers of tax, one at the corporate level and one at the shareholder level.

In contrast, the corporation could finance the same investment by borrowing money. When the corporation earns a profit from a debt-financed investment, it needs to pay the corporate income tax on its profits. But before the corporation pays its income tax, it needs to pay its lender back a portion of what it borrowed, plus interest. Under current law, corporations are able to deduct interest payments they make to lenders against their taxable incomeTaxable income is the amount of income subject to tax, after deductions and exemptions. For both individuals and corporations, taxable income differs from—and is less than—gross income. . Thus, profits derived from the debt-financed investment do not face a corporate level tax on the portion of the profit that is paid back in interest. The lender then receives the interest as income and needs to pay tax on it. The debt-financed project only nets a single layer of tax at the debt holder’s level.

Here’s a diagram of this current property of the tax code. It is definitely a bias or asymmetry worth reconsidering:

A description of the House plan from the Speaker’s office confirms the House was considering the issues described above:

The elimination of deductions for net interest helps to equalize the tax treatment of different types of financing and reduces tax-induced distortions in investment financing decisions. Providing neutrality takes the tax code out of marginal business decisions, letting market forces more efficiently allocate investment where it is most productive. It also eliminates a tax-based incentive for businesses to increase their debt load beyond the amount dictated by normal business conditions. A business sector that is leveraged beyond what is economically rational is more risky than a business sector with a more efficient debt-to-equity composition.

Several tax plans in the 2016 presidential campaign have considered elimination of the interest deduction, including Sen. Marco Rubio’s, which eliminated individual taxes so as to create a single layer of taxation, and former Gov. Jeb Bush’s, which kept two layers of taxation on both debt and equity investment. However, other lawmakers, such as Sen. Orrin Hatch, are looking to correct the same bias from another direction: by allowing a new deduction for dividends paid.

Share this article