TaxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. policy can influence business decisions in a variety of ways, some more easily influenced than others. One decision that the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 impacted is where companies choose to hold their intellectual property (IP). International trade data shows a significant shift of IP assets into the U.S. in 2017. However, if lawmakers change those tax policies and raise the cost of holding IP in the U.S., IP could start flowing abroad once again.

Intellectual property is a key driver in the current economy. Among other things, intellectual property includes patents for life-saving drugs and vaccines and software that runs applications on phones and computers.

Though IP can be incredibly valuable and support very profitable enterprises, in many cases it is simply a formula or lines of computer code. That makes it relatively easy for companies to choose where they put their IP; governments often use tax incentives to attract IP to their jurisdiction.

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act implemented several policies that made the U.S. more attractive as a location for IP, including lowering the corporate tax rate to 21 percent to be competitive with other countries.

It also introduced a new tax on foreign income in the form of Global Intangible Low-Tax Income (GILTI). This ensured that companies would pay a 10.5 to 13.125 percent rate (sometimes higher) on income from overseas. If a U.S. company moved IP out of the U.S. seeking a lower tax rate, then GILTI could require that company to pay additional taxes to the U.S. government.

In addition, and as a counterbalance to GILTI, the 2017 reform reduced the tax rate further on Foreign Derived Intangible Income (FDII), or income from exports related to IP held in the U.S., to 13.125 percent.

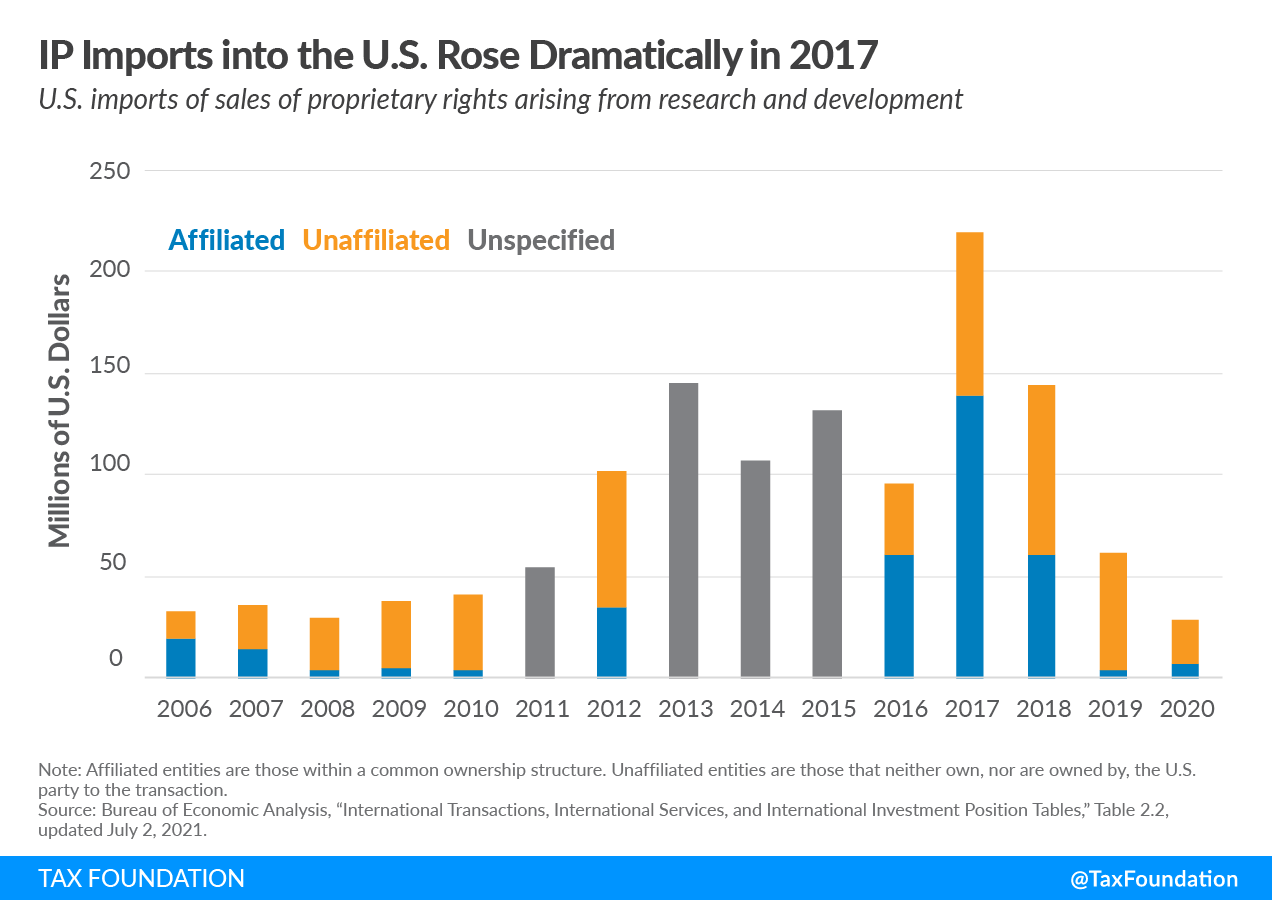

Companies responded to this by bringing an increased amount of IP assets into the U.S. In the five years prior to that tax reform, the U.S. imported an average of $116 million in IP rights each year according to data from the Bureau of Economic Analysis. In 2017, however, IP imports jumped to $219 million, a nearly 130 percent increase over the 2016 level and an 88 percent increase over the previous five-year average.

Additionally, 63 percent of those imports were from affiliated entities. This means that the imports into the U.S. came from related entities abroad.

While there was a large increase in IP imports around the time of tax reform, IP exports have continued apace, growing at a relatively consistent rate of 30 percent each year. In fact, IP exports have exceeded imports even since tax reform. In 2020, IP exports exceeded imports by $227 million, though the growth rate of those exports does not appear to have been impacted by tax reform.

In recent years, the vast majority (79 percent in 2018) of IP exports are to unrelated entities abroad rather than IP simply being sold to a foreign affiliate of a U.S. company. While incentives for bringing IP back into the U.S. appear to have changed, there is clearly a still growing foreign demand for IP developed in the U.S.

One country where U.S. companies have had a lot of IP-related activity in is Ireland. Recently, the Irish Finance Ministry released a report with data showing that patterns of payments for IP services (royalties) changed dramatically starting in 2020. Prior to 2020, royalty payments often went from Ireland to other offshore jurisdictions with very low or no corporate income taxes. In 2020, new Irish rules came into effect that removed benefits for business structures around IP and low-tax jurisdictions. Since the start of 2020, a significant share of royalty payments has gone directly from Ireland to the U.S.

While the BEA data do not directly mirror the data recently published by the Irish Ministry of Finance, they do show a 24 percent increase in exports associated with royalty payments from Ireland to the United States in 2020.

FDII does not only provide a tax benefit to exporters that move their IP to the U.S.—exporters that have kept their IP in the U.S. over the years also benefit from the reduced tax rate.

The pairing of GILTI and FDII was intended to balance the incentives for companies between foreign and domestic tax rates on IP income. However, that balance may change.

President Biden has proposed several corporate tax increases, including a higher corporate tax rate and higher GILTI taxes, as well as the replacement of FDII with a tax subsidy for research and development. The latter proposal has not been fully specified but would potentially shift the tax benefit away from the location of IP to the location of research and development activities.

Senators Ron Wyden (D-OR), Sherrod Brown (D-OH), and Mark Warner (D-VA) have also proposed changing FDII to be more in line with the location of innovative activities rather than the location of IP.

Until more details are released, it is unclear how these proposals will impact the incentives for companies that develop IP in the U.S. to keep that IP here or whether it will be more advantageous for companies to innovate elsewhere. Our current modeling of the Biden plan, which excludes the unspecified R&D subsidy, indicates the plan would reduce incentives to locate IP in the U.S.

As policymakers navigate the various options for changing FDII or the tax treatment of research and development, it is important to ensure that the U.S. remains an attractive place for companies to develop novel innovations that create significant value.

Share this article