Key Findings:

- The Tobacco TaxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. Equity Act would double taxes on cigarettes and equalize rates on all other tobacco and nicotine products to match the new higher cigarette rate.

- The increase would result in substantial increases on chewing tobacco (2,034 percent), pipe tobacco (1,651 percent), and snuff (over 1,677 percent). Vapor products, which are not currently taxed at the federal level, would also be taxed at the level of cigarettes.

- The increase could raise $112 billion over the 10-year budget window, but a large portion of the new tax burden would fall on low-income Americans, as consumption of tobacco is more common in this group. Moreover, the tax baseThe tax base is the total amount of income, property, assets, consumption, transactions, or other economic activity subject to taxation by a tax authority. A narrow tax base is non-neutral and inefficient. A broad tax base reduces tax administration costs and allows more revenue to be raised at lower rates. is increasingly narrow given the decades long decline in tobacco consumption.

- Tobacco products are taxed at multiple levels and with several levies. As a result of the federal increase, a pack-a-day smoker in New York state making $15,000 a year will pay almost 20 percent of his income in taxes on tobacco consumption.

- States stand to lose around $689 million in revenue from excise taxes on tobacco products due to the tax increase’s impact on consumption.

- Tax pyramidingTax pyramiding occurs when the same final good or service is taxed multiple times along the production process. This yields vastly different effective tax rates depending on the length of the supply chain and disproportionately harms low-margin firms. Gross receipts taxes are a prime example of tax pyramiding in action. will result in steep price increases in states with ad valorem (price-based) taxes on tobacco products, as federal increases are multiplied by the state level tax. Significant price increases can exacerbate issues with illicit trade.

- Tax parity between the most harmful tobacco products and least harmful nicotine products would hurt smokers’ ability to switch from cigarettes, which is a problem for public health.

Introduction

Federal tobacco taxes have not increased for over a decade. This year, a proposal, the Tobacco Tax Equity Act, from Senator Richard Durbin (D-IL) is gaining traction. [1] The proposal would increase rates on cigarettes by 100 percent and increase the rates on all other tobacco and nicotine products to achieve parity with the rate on cigarettes.

While a doubling of the cigarette tax yields a high rate, tax equity across products results in increases on other tobacco products that are significantly higher. The rate on chewing tobacco increases more than 2,000 percent, and the rates on pipe tobacco and snuff over 1,600 percent each. Vapor products, which have not been taxed at the federal level thus far, would be taxed at a rate equal to cigarettes, but the budget punts the design of this tax to the Department of Treasury.[2] In addition to the one-time increase, the rates would be indexed to inflationInflation is when the general price of goods and services increases across the economy, reducing the purchasing power of a currency and the value of certain assets. The same paycheck covers less goods, services, and bills. It is sometimes referred to as a “hidden tax,” as it leaves taxpayers less well-off due to higher costs and “bracket creep,” while increasing the government’s spending power. , which means they would automatically increase every year.[3]

| Product | Current Rate | Proposed Rate | Increase in Percent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cigarettes | $50.33 per thousand | $100.66 per thousand | 100% |

| Small Cigars | $50.33 per thousand | $100.66 per thousand | 100% |

| Large Cigars | 52.75 percent of manufacturer price but not more than 40.26 cents. | $49.56 per pound and a proportionate tax at the same rate on all fractional parts of a pound but not less than 10.066 cents per cigar | N/A |

| Chewing Tobacco | 50.33 cents per pound | $10.74 per pound | 2,034% |

| Snuff | $1.51 per pound | $26.84 per pound | 1,677% |

| Pipe Tobacco | $2.8311 per pound | $49.56 per pound | 1,651% |

| Roll-Your-Own Tobacco | $24.78 per pound | $49.56 per pound | 100% |

| Discrete Single-Use Unit | N/A | $100.66 per thousand | N/A |

| Vapor Products | N/A | TBD by the Department of Treasury | N/A |

|

Note: The term “discrete single-use unit” means any product containing, made from, or derived from tobacco or nicotine that is not intended to be smoked, and is in the form of a lozenge, tablet, pill, pouch, dissolvable strip, or other discrete single-use or single-dose unit. Source: Internal Revenue Code, 26 U.S. Code § 5701, S.1314, Tobacco Tax Equity Act of 2021. |

|||

The last time the federal excise taxAn excise tax is a tax imposed on a specific good or activity. Excise taxes are commonly levied on cigarettes, alcoholic beverages, soda, gasoline, insurance premiums, amusement activities, and betting, and typically make up a relatively small and volatile portion of state and local and, to a lesser extent, federal tax collections. on tobacco was increased was in 2009 to pay for a children’s health insurance programs. While the federal tax has not changed for 12 years, the average tax paid by consumers has increased significantly. Including the last federal increase, the average combined state and federal excise tax rate on tobacco has increased by more than 80 percent (the average state excise tax rate increased 65 percent between 2009 and 2021). The rate of inflation over that period is roughly 25 percent. Moreover, smoking has been declining at historic rates. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), as of 2019, 14.0 percent of American adults smoke.[4] In 2009, that figure was 20.6 percent.[5]

This analysis examines revenue potential, impact on tobacco consumers, impact on state revenue, and issues surrounding tax design.

Tax Design and Revenue Estimate

The first question to be answered when designing an excise tax is how to define the appropriate tax base. For most excise taxes, the base should be the harm or cost-causing element because that best internalizes a negative externalityAn externality, in economic terms, is a side effect or consequence of an activity that is not reflected in the cost of that activity, and not primarily borne by those directly involved in said activity. Externalities can be caused by either the production or consumption of a good or service and can be positive or negative. . Examples include the amount of tobacco plant intended for smoking, the alcohol content of a beverage, and sports bets’ monetary value. In other cases, where the tax is employed as a user feeA user fee is a charge imposed by the government for the primary purpose of covering the cost of providing a service, directly raising funds from the people who benefit from the particular public good or service being provided. A user fee is not a tax, though some taxes may be labeled as user fees or closely resemble them. , the tax base should be the best available proxy for use. For instance, consumption of motor fuel acts as a proxy for drivers’ use of public roads.[6] The federal tobacco tax generally does a good job at targeting externalities because it taxes quantity.

The next question is about tax rates, which is where the proposal fails. Equalizing tax rates between cigarettes and other tobacco products—both combustible and non-combustible—makes little sense if the tax is intended to internalize externalities associated with consumption. Harm to the user should be reflected by the tax rate, as social costs associated with consumption are lower for less harmful products. Taxing according to harm has the added benefit of allowing consumers to understand a product’s harm profile by using the price.

Rather than protecting public health, high excise taxes on lower-risk tobacco products jeopardize public health by pushing consumers back to smoking combustible products. If the policy goal of high taxes on cigarettes is to encourage cessation, taxation of other tobacco and nicotine products must be considered a part of that policy design.[7]

Lawmakers can make sure that the least harmful products are cheaper than the most harmful products by adhering to excise tax principles and levying a tax rate based on the negative externalities and associated costs. That strategy is utilized in some states, which have introduced provisions in their tax code cutting tax rates in half if the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) classifies a product with a modified risk tobacco product (MRTP) order.[8] These provisions should be encouraged and considered at the federal level.

According to Tax Foundation estimates, the tax increases would raise $112 billion over 10 years. The bulk of the revenue, $74.8 billion, is from the doubling of cigarette taxes. The tax on vapor products would raise roughly $15 billion over 10 years.[9]

| Product | Revenue over 10 years |

|---|---|

| Cigarettes | $74.8 billion |

| Other Tobacco Products | $21.9 billion |

| Vapor Products | $15.3 billion |

| Total | $112 billion |

|

Source: Author’s calculations. |

|

While the increase will raise substantial revenue, excise taxes should not be considered a stable revenue source, since they are so narrowly imposed.[10] Decades of declining use means that tobacco taxes generally raise less revenue with each passing year. In addition, the narrow tax base exposes the revenue to non-tax-related regulatory policy. For example, the FDA has recently announced its intent to ban the sale of menthol cigarettes nationwide.[11] If the lesson out of Massachusetts is any indication, such a ban, which would criminalize the sale of over a third of the current national market, could have a massive impact on revenue generation.[12] Massachusetts has collected roughly 25 percent less revenue since imposing a menthol ban in June 2020,[13] and while Massachusetts has to contend with smuggling of menthol cigarettes from other states where they are still legal, a federal ban would likely lead to a rise in international smuggling of menthol cigarettes.

Although tobacco taxes (and other excise taxes) have historically been a general fund revenue tool, revenue from excise taxes should be allocated to cover societal costs related to consumption.[14] This means, to cite a few examples, health costs related to smoking, infrastructure costs associated with driving, and costs related to enforcing bans of driving under the influence and regulating the sale of alcohol. In the President’s plan, the revenue is allocated to pay for the spending in the American Family Plan Act.

Regressivity

A large portion of this new tax burden will be paid by lower-income Americans. By itself, the fact that some excise taxes have regressive effects is no argument against levying them—a user-pays system or the internalization of meaningful externalities can be good policy—but the effect does illustrate the importance of not relying on regressive excise taxes for general fund revenue. It also underscores that trying to maximize revenue generation from excise taxes can carry adverse effects.

Not all excise taxes are created equal: for some excise taxes, the regressivity is exacerbated by disproportionate consumption patterns, and not just that low-income households consume more of their income overall. For instance, smoking incidence grows as income declines, which means that tobacco excise taxes are unusually regressive. According to one report, 26.5 percent of American adults making less than $25,000 a year smoke, but only 9.3 percent of American adults making more than $75,000 smoke.[15]

As Table 3 shows, excise tax burden on highways, air travel, and alcohol generally follows the income distribution by income group. This is truer for taxes on air travel and less so for highway and alcohol taxes. Tobacco taxes, however, stand out. Although the nominal tax burden does increase with income, it is much flatter than the other categories, and thus more regressive as a percentage of income.

| Highway | Air Travel | Alcohol | Tobacco | Income distribution | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lowest quintile | 4.2% | 4.5% | 3.5% | 15.9% | 3.1% | |

| Second quintile | 10.5% | 7.0% | 8.6% | 18.3% | 8.3% | |

| Middle quintile | 17.1% | 14.1% | 17.2% | 18.1% | 14.1% | |

| Fourth quintile | 23.4% | 21.6% | 23.9% | 20.1% | 22.7% | |

| Top quintile | 44.4% | 52.4% | 46.7% | 27.3% | 51.9% | |

| Total | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | |

|

Note: aggregates may not equal 100% due to rounding. Sources: Urban Brookings Tax Policy Center, “Who bears the burden of federal excise taxes?” https://www.taxpolicycenter.org/briefing-book/who-bears-burden-federal-excise-taxes; and U.S. Census Bureau, “Income and Poverty in the United States: 2019,” Sept. 15, 2020, https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2020/demo/p60-270.html. |

||||||

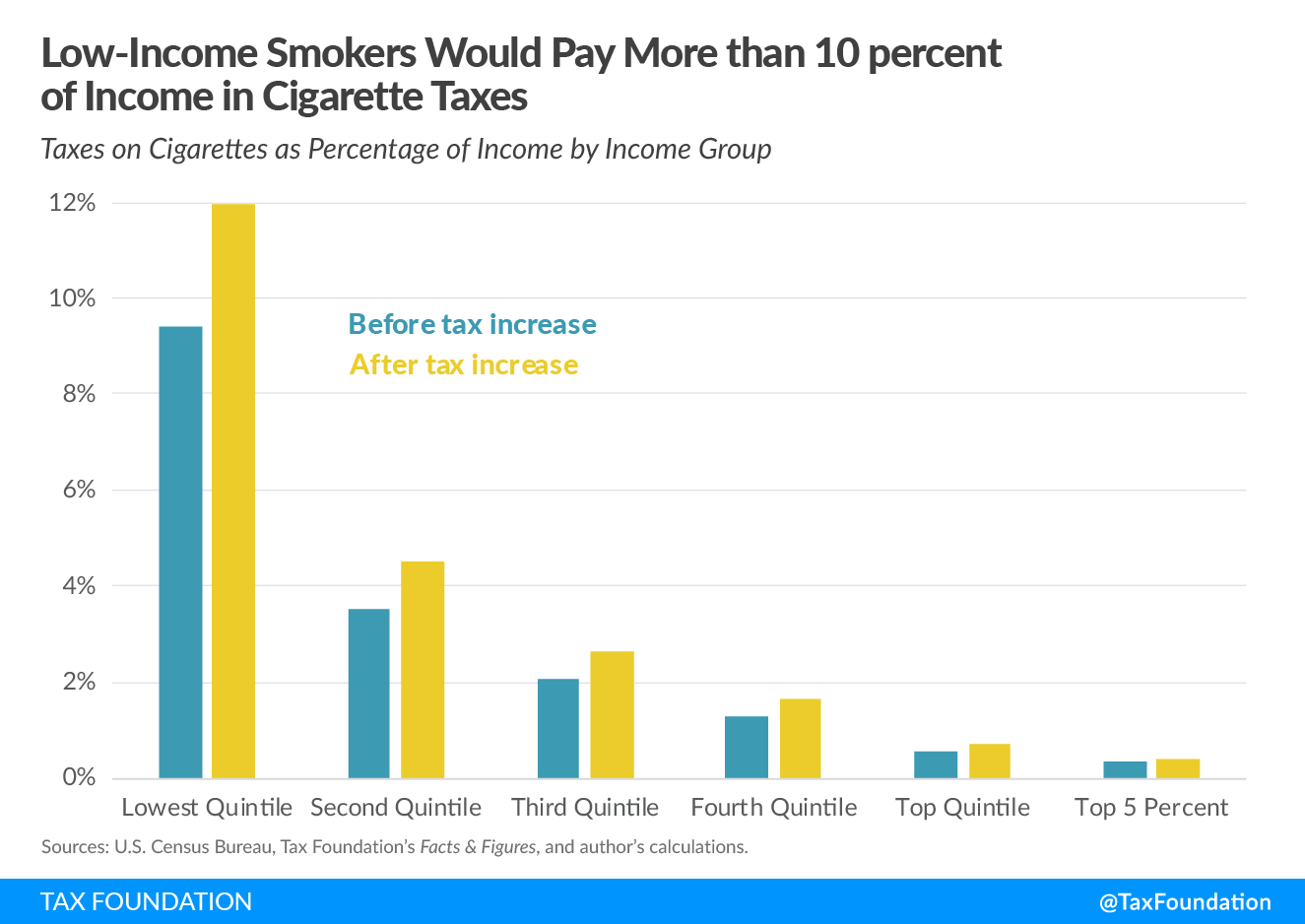

This distribution of tax burden impacts how excise tax increases affect taxpayers. The proposed increase to the federal tobacco tax would negatively impact the lowest quintile’s after-tax income by 0.51 percent whereas the top quintile would only see a 0.051 percent decline in after-tax incomeAfter-tax income is the net amount of income available to invest, save, or consume after federal, state, and withholding taxes have been applied—your disposable income. Companies and, to a lesser extent, individuals, make economic decisions in light of how they can best maximize their earnings. —one-tenth of the impact.

Another way to show this regressive effect is in actual tax burden. As mentioned above, the Tax Foundation estimates that the increase of tobacco taxes would raise approximately $112 billion in federal revenue over 10 years. If that additional burden is distributed similar to the existing burden, the lowest quintile would pay $17.8 billion more in federal taxes on tobacco and the top quintile would pay $30.6 billion more in federal taxes on tobacco. While the top quintile pays more actual tax, they also earn 51.9 percent of total income. Comparatively, Americans in the lowest quintile earn 3.1 percent of total income. Additional taxes paid by the lowest quintile are 58 percent of the additional taxes paid by the top quintile, but income is only 6 percent of the top quintile’s.

Using the figures in the different quintiles makes it possible to illustrate the difference in tax burden for taxpayers. Before a tax increase, a taxpayer making around $15,000 (mean income in the lowest quintile) would pay $90 annually in federal cigarette taxes, and a taxpayer making $254,000 would pay $127 annually. After a federal increase, those numbers rise to $150 and $254, respectively. Even this, however, does not tell the whole story. Far from everyone in each quintile uses tobacco products, which means the impact on the individual consumer will be much higher.

Moreover, the federal excise tax is not the only tax levied on tobacco products. All states and many localities levy additional excise taxes, and most states levy the general sales taxA sales tax is levied on retail sales of goods and services and, ideally, should apply to all final consumption with few exemptions. Many governments exempt goods like groceries; base broadening, such as including groceries, could keep rates lower. A sales tax should exempt business-to-business transactions which, when taxed, cause tax pyramiding. on the products as well. In addition, tobacco companies pay settlement agreement money to the states.[16] These costs are, similar to excise taxes, passed onto consumers.

When purchasing a pack of cigarettes, the average cigarette smoker currently pays:

- $1.01 in federal excise tax,

- $1.91 in state excise tax,

- $0.66 in master settlement cost, and

- $0.36 in average state sales tax[17]

For a pack-a-day smoker that translates to roughly $1,435 per year in taxes on cigarettes, but the proposal would increase that total to $1,823 per year. For low-income Americans, these figures represent a significant portion of their income, and the majority of smokers have lower incomes.[18]

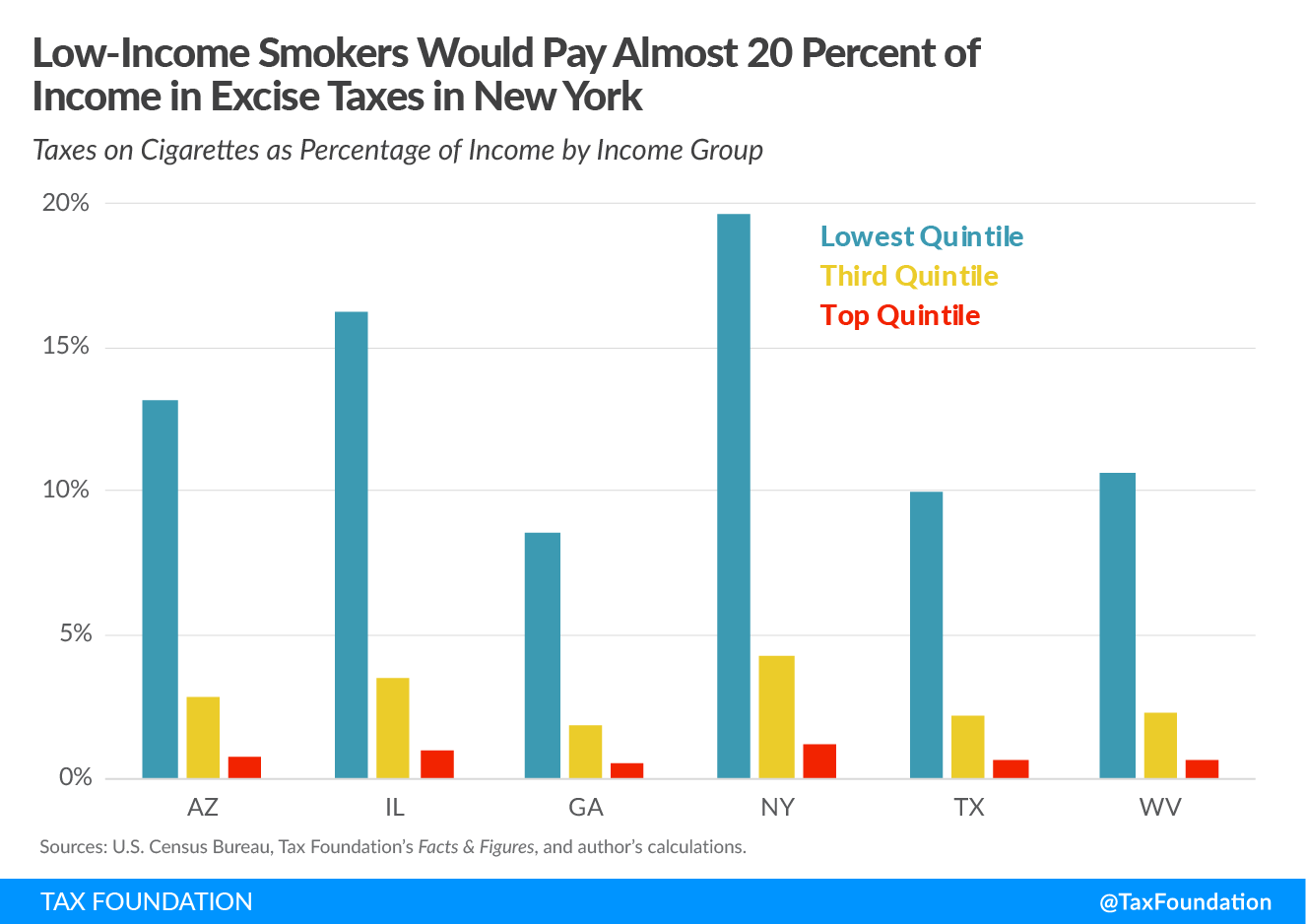

State by state, these figures differ based on the rate of the excise taxes levied by the state. For instance, in a high-tax state like New York, a pack-a-day smoker making $15,000 pays roughly 17 percent of his income in tobacco taxes at current tax levels, but this would increase to 19.6 percent if federal cigarette taxes double. It would be even worse in New York City, where low-income smokers would pay close to 24 percent of their income in tobacco taxes. In a low-tax state like Georgia, the rates are 5.9 percent and 8.5 percent, respectively.

| State | State excise tax | Total tax paid per pack before federal increase | Tax per year for pack-a-day smoker before federal increase | Total tax paid per pack after federal increase | Tax per year for pack-a-day smoker after federal increase | Difference in annual tax payments after increase | Rate as percentage of income for a smoker making $15,000 a year after tax Increase |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arizona | $2.00 | $4.32 | $1,575.54 | $5.41 | $1,974.85 | $399.31 | 13.2% |

| Georgia | $0.37 | $2.42 | $884.84 | $3.51 | $1,280.48 | $395.64 | 8.5% |

| Illinois | $2.98 | $5.54 | $2,023.57 | $6.65 | $2,428.20 | $404.63 | 16.2% |

| New York | $4.35 | $6.95 | $2,534.99 | $8.04 | $2,935.05 | $400.06 | 19.6% |

| Texas | $1.41 | $3.63 | $1,325.05 | $4.72 | $1,723.90 | $398.84 | 11.5% |

| West Virginia | $1.20 | $3.29 | $1,201.05 | $4.37 | $1,593.66 | $392.61 | 10.6% |

|

Sources: Tax Foundation’s Facts & Figures, and author’s calculations. |

|||||||

The following is an illustration of the same states comparing the effective rates as a percentage of income for smokers in the lowest quintile, middle quintile, and top quintile. Although impact on the individual smoker differs based on state, the regressivity of the tax is a recurring theme across all 50 states and the District of Columbia, and it is hard to reconcile with President Biden’s pledge to not raise taxes on Americans earning less than $400,000.

State Tax Collections and Tax Pyramiding

Having multiple levels of taxation impacts tobacco consumers, but it also impacts state collections. Because consumption is affected by retail price, a federal tax hike, which would translate to increased retail prices and a decline in consumption, can impact the revenue generated by state governments.

If the federal government doubles taxes on a pack of 20 cigarettes, and this increase were passed on to consumers, state governments would in aggregate raise roughly $689 million less in revenue from excise taxes on cigarettes in the first full year after implementation.[19] In addition, when taxpayers pay more in tobacco taxes, they pay less in other taxes like income and payroll taxes. This effect is known as the Income and Payroll Offset. Generally, additional revenue generated by increased excise taxes is reduced by around 25 percent as a result of this offset.[20]

| Example of Impact of Federal Excise Tax Increase on State Excise Revenue in Arizona, Illinois, and Washington, 2020 Data | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State | Cigarette tax revenue 2020 | Current retail price | Federal tax increase | Simulated revenue after increase | Difference |

| Arizona | $275,350,000 | $7.70 | $1.01 | $263,990,641 | $11,359,359 |

| Illinois | $796,118,000 | $9.16 | $1.01 | $768,327,245 | $27,790,755 |

| Washington | $331,349,000 | $8.94 | $1.01 | $319,475,078 | $11,873,922 |

|

Note: Elasticity assumed at -0.3, tax increase assumed to be passed to consumer. Price effect of increased general sales tax included but local taxes and Income and Payroll Offset are excluded. Sources: U.S. Census Bureau, “State Government Tax Tables”; William Orzechowski and Robert Walker, The Tax Burden on Tobacco: Historical Compilation 54 (February 2020); author’s calculations. |

|||||

The preceding is only an illustration of the effect on cigarette consumption, but excise tax design in many states could spell bigger trouble for other tobacco products. All but three states levy their tax on other tobacco products on an ad valorem basis, and these ad valorem taxes will result in additional pyramiding after federal increases.

As an example, Massachusetts levies a 210 percent tax on wholesale value on smokeless tobacco. Dip, which under the bill would be taxed at $26.84 per pound, would in Massachusetts be multiplied by the additional 210 percent state tax.

Today, dip is federally taxed at $1.51 per pound, which translates to $4.68 per pound after adding the 210 percent state tax in Massachusetts. With the proposed increase, the tax burden in Massachusetts would be $83.20 per pound, because Massachusetts’ tax would be imposed on a price that includes the higher federal tax. This is an increase of 1,677 percent.

An increase of that size would result in a standard can of 1.2 ounces carrying a tax of $6.24 in pure excise taxes before markups, sales taxes, and fees. That is versus $0.35 for a 1.2 ounce can today. Such a substantial tax increase is likely to translate to a dramatic increase of retail prices in the state.

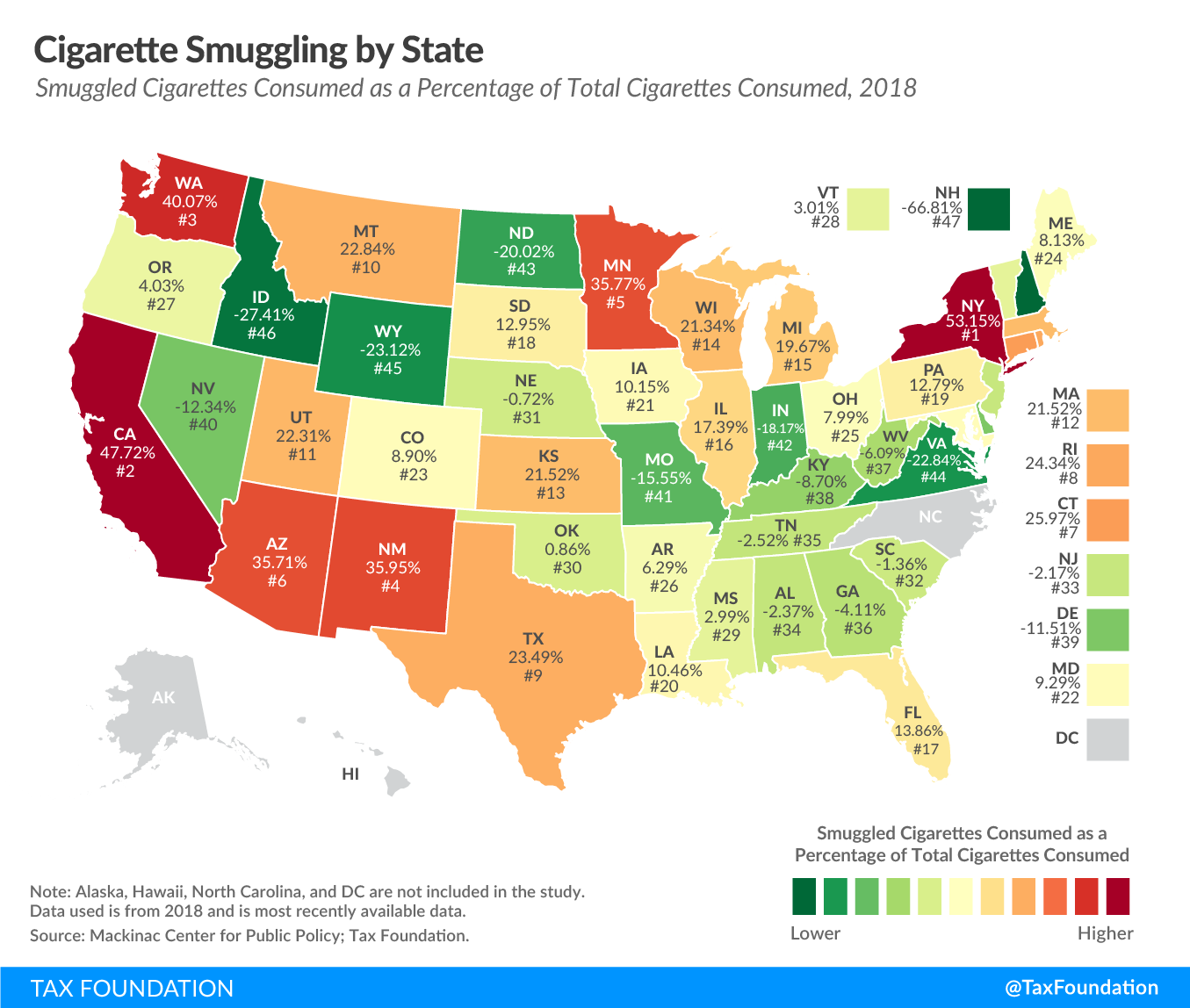

These problems of pyramiding and increasing costs can exacerbate issues surrounding illicit trade (which could further reduce state tax collections). Illicit trade with tobacco products is a global multibillion-dollar operation, which often involves some of the world’s worst criminals.[21] In the U.S., the states that suffer the most from smuggled tobacco products are those where cheaper products are easily available.[22]

Impact of New Vapor Tax

From a pure public health standpoint, the rationale for taxing all nicotine products, and not just traditional tobacco products, is not very strong. It is generally believed beneficial for society every time a smoker becomes a vaper. While more research relating to the potential harm-reduction qualities of vapor products is needed, for now, the consensus is that vapor products are less harmful than traditional combustible tobacco products.[23] Public Health England, an agency of the English Ministry for Health, concludes that vapor products are 95 percent less harmful than cigarettes.[24]

Before discussing the trade-offs in nicotine tax policy design, it is important to introduce the concept of harm reduction. This is the notion that it is more practical to reduce harm associated with use of certain goods rather than to attempt to eliminate it completely through bans or punitive levels of taxation. This concept is relevant because vapor products are less harmful than combustible tobacco products. Combine that with the fact that about 70 percent of America’s 34 million smokers are interested in quitting, but only have a success rate of about 7 percent (10 percent among younger smokers[25]), and vapor products—even if unhealthy in their own right—are highly attractive as an alternative to smoking. The main reason for the low success rate in smoking cessation is the addictive nature of nicotine. To put it simply: it is very difficult to quit.

Consequently, vapor products could be a key tool in the fight against tobacco-related morbidity and mortality. Protecting access to harm-reducing vapor products is connected to excise tax design as nicotine-containing products are substitute goods. One study found that a vapor excise tax of $1.65 per milliliter of liquid would drive 2.5 million people back to smoking. [26]

Another publication looked at cessation behaviors in the context of a tax increase on vapor products and found that 32,400 smokers in Minnesota were deterred from quitting cigarettes after the state implemented a 95 percent excise tax on vapor products.[27] The substitution effect is also evident looking at the smoking rates in the U.S. There is some correlation, and likely partial causality, between recent growth in the vapor market and the pace at which the cigarette market is declining. While vaping has been growing in many states, the decline in smoking has accelerated—especially among teens and young adults.

As mentioned previously, the federal government recognizes the harm reducing potential of certain tobacco products through the FDA’s Modified Risk Tobacco Product (MRTP) application lane. A product granted an MTRP order has proven to benefit the health of the population as a whole.[28] Any product with such an order has, in other words, been proven to have fewer negative externalities associated with consumption. Tax rates should reflect this. On way to do this is to include triggers that cut the tax rate for products which obtain MRTP orders—something several states already do.[29]

To the extent that legislators do choose to tax nicotine products, they should design a principled excise regime. For a new category like vapor product, the first step is clear definitions. Unfortunately, the proposal leaves it up to the Department of Treasury to define the product and design the tax base.

Any tax of vapor products should be specific, based on quantity. The obvious choice is to tax the liquid based on volume (e.g., a certain amount per ml). However, designing a neutral tax is not as simple as it may seem given that vapor products are not all similar. Closed systems typically have higher nicotine content than open systems.[30] Thus, legislators could consider establishing a tiered system, where open refillable systems are taxed at a lower rate than closed systems, with different rates designed to equalize taxation and keep it neutral, not introduce unnecessary disparities.

The level (dollar amount) of the excise tax should reflect the harm of nicotine products relative to traditional tobacco products. Recently, the Royal College of Physicians released a report recommending a tax of 5 percent relative to the tax on combustible tobacco. To illustrate how that would work in the context of this proposal: if a pack of cigarettes is taxed at $2.00, the vapor products tax should be $0.10 per pod for closed systems, since a pod is a substitute for one pack of cigarettes.[31] For open products, a lower rate could make sense to account for the difference in consumption method (pod often contains much less liquid than non-pod systems).

Of course, vapor products are not the only disruptive product on the nicotine market. Discrete single-use units (nicotine pouches), small non-tobacco-containing pouches that consumers place in their mouth; heated tobacco products, tobacco products without combustion; and snus, pasteurized oral tobacco, have all grown market share over the last few years. Taxation of these products should follow the same principles as the taxation of vapor products. If they are proven to reduce risk associated with nicotine consumption, they should be taxed at lower rates. Below is a quick guide to appropriate tax base choices.

| Product | Design |

|---|---|

| Vapor Products | Specific per milliliter (potentially bifurcated) |

| Snus | Specific per ounce |

| Discrete Single-Use Unit | Specific per ounce |

| Heated tobacco | Specific by weight or quantity |

|

Source: Author’s analysis. |

|

As a revenue tool rather than a public health tool, the vapor products tax might be tempting. Some of the decline in revenue from traditional tobacco can be made up by taxing other nicotine consumers more. However, assuming the rationale for taxing tobacco involved considerations beyond mere revenue (and it should), the harm-reduction potential of vapor products may advise against this. Even a revenue rationale still leaves questions around the justification for targeting a single product and group of consumers for revenue.

Reasonable Reform

There are legitimate reasons to update parts of the current tax code. For instance, the current inequities between pipe tobacco and roll-your-own tobacco and between small and large cigars make little sense since the externalities associated with use are close to identical. This inequity has produced a virtually nonexistent market for roll-your-own, as consumers simply use pipe tobacco instead. According to the Government Accountability Office (GAO), market shifts stemming from flawed tax design have resulted in between $2.5 billion and $3.9 billion in lost federal revenue between 2009 and 2018.[32] Fixing these problems or imposing moderate adjustments would solve problems while limiting risks of unintended consequences such as additional illicit trade and discouraging smokers from switching.

However, the proposal’s intent of achieving parity across a wide product portfolio containing non-combustible and non-tobacco products goes too far and would hurt consumer access to harm-reducing products. Moreover, doubling the cigarette excise tax rate moves the rate far beyond internalizing externalities. It is not aligned with the health costs of smoking and is not intended to be; it is, primarily, a source of additional revenue, and must be evaluated in those terms.

Conclusion

Footing smokers with a tax of $112 billion to pay for non-smoking-related expenses is not advisable. The tax is not only highly regressive, it also can result in unintended consequences. Because of the tax parity between the most harmful tobacco products and the least harmful nicotine products, smokers will be discouraged from switching, which would be a public health loss. The significant price increases that would result from the increase could also further increase illicit trade, which is already a huge problem in many states.

Federal lawmakers should not consider tobacco excise taxes a stable revenue source for long-term spending, and they should remember that increases at the federal level will impact state tax collections negatively.

Excise taxes are legitimate when certain negative externalities associated with a type of transaction or type of consumption can be identified, and they can work well to establish user-fee systems. Lawmakers looking to generate stable revenue for general recurring spending priorities, however, should raise that through broad-based taxes at low rates instead.

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

Subscribe| State | State excise tax | Total tax paid per pack before federal increase | Tax per year for pack-a-day smoker before federal increase | Total tax paid per pack after federal increase | Tax per year for pack-a-day smoker after federal increase | Difference in annual tax payments after increase | Rate as percentage of income for a smoker making $15,000 a year after tax Increase |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AL | $0.68 | $2.84 | $1,038.19 | $3.95 | $1,440.83 | $402.64 | 9.6% |

| AK | $2.00 | $3.84 | $1,403.13 | $4.87 | $1,778.27 | $375.14 | 11.9% |

| AZ | $2.00 | $4.32 | $1,575.54 | $5.41 | $1,975.16 | $399.62 | 13.2% |

| AR | $1.15 | $3.44 | $1,255.27 | $4.55 | $1,658.98 | $403.71 | 11.1% |

| CA | $2.87 | $5.27 | $1,923.55 | $6.37 | $2,324.19 | $400.65 | 15.5% |

| CO | $0.84 | $2.99 | $1,092.35 | $4.08 | $1,489.46 | $397.11 | 9.9% |

| CT | $4.35 | $6.68 | $2,437.58 | $7.75 | $2,829.64 | $392.06 | 18.9% |

| DE | $2.10 | $3.77 | $1,376.05 | $4.78 | $1,744.70 | $368.65 | 11.6% |

| DC | $4.98 | $7.29 | $2,662.24 | $8.36 | $3,053.01 | $390.77 | 20.4% |

| FL | $1.34 | $3.48 | $1,269.41 | $4.56 | $1,664.16 | $394.75 | 11.1% |

| GA | $0.37 | $2.42 | $ 884.84 | $3.51 | $1,280.48 | $395.64 | 8.5% |

| Hl | $3.20 | $5.30 | $1,933.39 | $6.35 | $2,318.40 | $385.02 | 15.5% |

| ID | $0.57 | $2.60 | $ 948.69 | $3.67 | $1,339.57 | $390.88 | 8.9% |

| IL | $2.98 | $5.54 | $2,023.57 | $6.65 | $2,428.20 | $404.63 | 16.2% |

| IN | $1.00 | $3.10 | $1,130.16 | $4.18 | $1,524.62 | $394.46 | 10.2% |

| IA | $1.36 | $3.49 | $1,272.83 | $4.57 | $1,667.06 | $394.23 | 11.1% |

| KS | $1.29 | $3.53 | $1,289.62 | $4.63 | $1,690.30 | $400.69 | 11.3% |

| KY | $1.10 | $3.14 | $1,144.64 | $4.21 | $1,535.41 | $390.77 | 10.2% |

| LA | $1.08 | $3.35 | $1,222.18 | $4.45 | $1,625.92 | $403.75 | 10.8% |

| ME | $2.00 | $4.09 | $1,491.86 | $5.15 | $1,880.78 | $388.93 | 12.5% |

| MD | $3.75 | $5.87 | $2,142.31 | $6.94 | $2,533.08 | $390.77 | 16.9% |

| MA | $3.51 | $5.80 | $2,118.71 | $6.88 | $2,510.40 | $391.69 | 16.7% |

| MI | $2.00 | $4.11 | $1,500.32 | $5.18 | $1,891.09 | $390.77 | 12.6% |

| MN | $3.65 | $6.02 | $2,196.96 | $7.10 | $2,593.11 | $396.15 | 17.3% |

| MS | $0.68 | $2.77 | $1,009.49 | $3.85 | $1,404.20 | $394.71 | 9.4% |

| MO | $0.17 | $2.27 | $ 829.87 | $3.37 | $1,228.93 | $399.06 | 8.2% |

| MT | $1.70 | $3.37 | $1,230.05 | $4.38 | $1,598.70 | $368.65 | 10.7% |

| NE | $0.64 | $2.73 | $ 995.69 | $3.81 | $1,389.93 | $394.23 | 9.3% |

| NV | $1.80 | $4.06 | $1,481.87 | $5.15 | $1,880.86 | $398.99 | 12.5% |

| NH | $1.78 | $3.45 | $1,259.25 | $4.46 | $1,627.90 | $368.65 | 10.9% |

| NJ | $2.70 | $4.91 | $1,793.74 | $5.99 | $2,186.73 | $392.98 | 14.6% |

| NM | $2.00 | $4.26 | $1,553.61 | $5.35 | $1,951.13 | $397.52 | 13.0% |

| NY | $4.35 | $6.95 | $2,534.99 | $8.04 | $2,935.05 | $400.06 | 19.6% |

| NC | $0.45 | $2.51 | $ 917.87 | $3.60 | $1,312.25 | $394.38 | 8.7% |

| ND | $0.44 | $2.51 | $ 915.61 | $3.59 | $1,309.92 | $394.31 | 8.7% |

| OH | $1.60 | $3.77 | $1,376.30 | $4.85 | $1,771.60 | $395.30 | 11.8% |

| OK | $2.03 | $3.70 | $1,350.50 | $4.71 | $1,719.15 | $368.65 | 11.5% |

| OR | $1.33 | $3.00 | $1,095.00 | $4.01 | $1,463.65 | $368.65 | 9.8% |

| PA | $2.60 | $4.81 | $1,754.05 | $5.88 | $2,146.07 | $392.02 | 14.3% |

| RI | $4.25 | $6.64 | $2,422.51 | $7.72 | $2,816.96 | $394.46 | 18.8% |

| SC | $0.57 | $2.68 | $ 978.14 | $3.77 | $1,374.29 | $396.15 | 9.2% |

| SD | $1.53 | $3.65 | $1,332.92 | $4.73 | $1,725.17 | $392.24 | 11.5% |

| TN | $0.62 | $2.85 | $1,040.18 | $3.96 | $1,444.04 | $403.86 | 9.6% |

| TX | $1.41 | $3.63 | $1,325.05 | $4.72 | $1,723.90 | $398.84 | 11.5% |

| UT | $1.70 | $3.89 | $1,421.65 | $4.98 | $1,816.81 | $395.16 | 12.1% |

| VT | $3.08 | $5.32 | $1,940.51 | $6.39 | $2,332.16 | $391.65 | 15.5% |

| VA | $0.60 | $2.63 | $ 961.19 | $3.70 | $1,350.96 | $389.77 | 9.0% |

| WA | $3.03 | $5.52 | $2,014.72 | $6.62 | $2,417.40 | $402.68 | 16.1% |

| WV | $1.20 | $3.29 | $1,201.05 | $4.37 | $1,593.66 | $392.61 | 10.6% |

| WI | $2.52 | $4.63 | $1,689.33 | $5.69 | $2,078.00 | $388.67 | 13.9% |

| WY | $0.60 | $2.59 | $ 945.78 | $3.66 | $1,334.08 | $388.30 | 8.9% |

|

Notes: Mean income of $15,286 used for effective rate in lowest income quintile. Sources: U.S. Census Bureau, William Orzechowski and Robert Walker, The Tax Burden on Tobacco: Historical Compilation 54 (February 2020), Tax Foundation’s Facts & Figures, and author’s calculations. |

|||||||

| State | Cigarette tax revenue 2020 | Current retail price | Federal tax increase | Retail price after increase | Simulated revenue after increase | Difference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AL | $160,234,000 | $6.09 | $1.01 | $7.10 | $152,227,636 | $8,006,364 |

| AK | $42,905,000 | $9.90 | $1.01 | $10.91 | $41,591,847 | $1,313,153 |

| AZ | $275,350,000 | $7.70 | $1.01 | $8.71 | $263,990,641 | $11,359,359 |

| AR | $159,421,000 | $6.51 | $1.01 | $7.52 | $151,596,763 | $7,824,237 |

| CA | $1,708,582,000 | $8.41 | $1.01 | $9.42 | $1,642,593,113 | $65,988,887 |

| CO | $139,993,000 | $6.25 | $1.01 | $7.26 | $133,041,575 | $6,951,425 |

| CT | $322,776,000 | $10.37 | $1.01 | $11.38 | $312,807,006 | $9,968,994 |

| DE | $106,785,000 | $7.34 | $1.01 | $8.35 | $102,376,845 | $4,408,155 |

| DC | $25,094,000 | $10.73 | $1.01 | $11.74 | $24,347,041 | $746,959 |

| FL | $992,778,000 | $6.62 | $1.01 | $7.63 | $945,044,401 | $47,733,599 |

| GA | $159,616,000 | $5.62 | $1.01 | $6.63 | $150,983,305 | $8,632,695 |

| Hl | $102,445,000 | $9.62 | $1.01 | $10.63 | $99,103,130 | $3,341,870 |

| ID | $33,580,000 | $5.96 | $1.01 | $6.97 | $31,788,434 | $1,791,566 |

| IL | $796,118,000 | $9.16 | $1.01 | $10.17 | $768,327,245 | $27,790,755 |

| IN | $361,033,000 | $6.16 | $1.01 | $7.17 | $342,244,796 | $18,788,204 |

| IA | $173,944,000 | $6.59 | $1.01 | $7.60 | $165,542,897 | $8,401,103 |

| KS | $117,028,000 | $6.60 | $1.01 | $7.61 | $111,361,931 | $5,666,069 |

| KY | $360,712,000 | $6.10 | $1.01 | $7.11 | $341,904,617 | $18,807,383 |

| LA | $235,890,000 | $6.29 | $1.01 | $7.30 | $224,104,493 | $11,785,507 |

| ME | $120,611,000 | $7.59 | $1.01 | $8.60 | $115,567,819 | $5,043,181 |

| MD | $323,680,000 | $7.49 | $1.01 | $8.50 | $309,910,524 | $13,769,476 |

| MA | $477,366,000 | $10.00 | $1.01 | $11.01 | $462,093,253 | $15,272,747 |

| MI | $785,451,000 | $7.34 | $1.01 | $8.35 | $751,360,304 | $34,090,696 |

| MN | $502,452,000 | $9.37 | $1.01 | $10.38 | $485,213,525 | $17,238,475 |

| MS | $105,223,000 | $5.88 | $1.01 | $6.89 | $99,489,496 | $5,733,504 |

| MO | $72,999,000 | $5.43 | $1.01 | $6.44 | $68,919,813 | $4,079,187 |

| MT | $64,436,000 | $7.24 | $1.01 | $8.25 | $61,739,300 | $2,696,700 |

| NE | $48,383,000 | $6.02 | $1.01 | $7.03 | $45,837,098 | $2,545,902 |

| NV | $166,468,000 | $7.17 | $1.01 | $8.18 | $159,022,406 | $7,445,594 |

| NH | $199,476,000 | $7.15 | $1.01 | $8.16 | $191,022,681 | $8,453,319 |

| NJ | $560,200,000 | $8.25 | $1.01 | $9.26 | $538,437,076 | $21,762,924 |

| NM | $79,834,000 | $7.49 | $1.01 | $8.50 | $76,451,610 | $3,382,390 |

| NY | $949,631,000 | $10.86 | $1.01 | $11.87 | $922,177,081 | $27,453,919 |

| NC | $235,350,000 | $5.66 | $1.01 | $6.67 | $222,058,940 | $13,291,060 |

| ND | $19,646,000 | $5.73 | $1.01 | $6.74 | $18,564,620 | $1,081,380 |

| OH | $831,477,000 | $6.93 | $1.01 | $7.94 | $793,119,106 | $38,357,894 |

| OK | $372,123,000 | $7.54 | $1.01 | $8.55 | $357,168,986 | $14,954,014 |

| OR | $187,697,000 | $6.82 | $1.01 | $7.83 | $179,357,969 | $8,339,031 |

| PA | $1,139,442,000 | $8.45 | $1.01 | $9.46 | $1,096,437,772 | $43,004,228 |

| RI | $129,026,000 | $10.24 | $1.01 | $11.25 | $124,968,627 | $4,057,373 |

| SC | $134,978,000 | $5.90 | $1.01 | $6.91 | $127,704,135 | $7,273,865 |

| SD | $40,899,000 | $7.06 | $1.01 | $8.07 | $39,076,332 | $1,822,668 |

| TN | $216,307,000 | $5.86 | $1.01 | $6.87 | $204,345,350 | $11,961,650 |

| TX | $1,130,873,000 | $6.72 | $1.01 | $7.73 | $1,077,195,090 | $53,677,910 |

| UT | $84,845,000 | $7.30 | $1.01 | $8.31 | $81,139,495 | $3,705,505 |

| VT | $58,010,000 | $9.08 | $1.01 | $10.09 | $55,971,526 | $2,038,474 |

| VA | $131,964,000 | $6.34 | $1.01 | $7.35 | $125,377,999 | $6,586,001 |

| WA | $331,349,000 | $8.94 | $1.01 | $9.95 | $319,475,078 | $11,873,922 |

| WV | $153,015,000 | $6.47 | $1.01 | $7.48 | $145,488,912 | $7,526,088 |

| Wl | $523,557,000 | $8.07 | $1.01 | $9.08 | $503,043,495 | $20,513,505 |

| WY | $15,149,000 | $6.03 | $1.01 | $7.04 | $14,362,550 | $786,450 |

| Total | $16,466,201,000 | $7.42 | $1.01 | $8.43 | $15,777,075,684 | $689,125,316 |

|

Note: Elasticity assumed at -0.3, tax increase assumed to be passed to consumer. Price effect of increased general sales tax included but local taxes and Income and Payroll Offset are excluded. Sources: U.S. Census Bureau, “State Government Tax Tables”; William Orzechowski and Robert Walker, The Tax Burden on Tobacco:Historical Compilation54 (February 2020); author’s calculations. |

||||||

[1] Congress.gov, “S.1314: Tobacco Tax Equity Act of 2021,” https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/senate-bill/1314.

[2] ibid.

[3] Inflation adjustments can make sense if a tax rate is at an appropriate level that captures externalities. That is not the case for these rates.

[4] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “Current Cigarette Smoking Among Adults in the United States,” Dec. 10, 2020, https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/fact_sheets/adult_data/cig_smoking/index.htm.

[5] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “Vital Signs: Current Cigarette Smoking Among Adults Aged ≥18 Years — United States, 2009,” Sept. 10, 2010, https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5935a3.htm#:~:text=In%202009%2C%20an%20estimated%2020.6,17.9%25)%20(Table).

[6] This particular tax base may become obsolete in the near future. For a discussion on modernizing transportation taxes, see Ulrik Boesen, “Who Will Pay for the Roads?” Tax Foundation, Aug. 25, 2020, https://www.taxfoundation.org/road-funding-vehicle-miles-traveled-tax/.

[7] More on substitutive effects between tobacco and nicotine products in the section about the vapor tax.

[8] The FDA recognizes harm reduction by granting different levels of authorization to market tobacco products—Premarket Tobacco Application (PMTA) and Modified Risk Tobacco Product Application (MRTP). Lawmakers should take advantage of the rigorous analysis conducted by the FDA in connection with these applications to understand harm profile and tax rates. See Stephanie L. Redus, “PMTA And MRTPA Review Process,” U.S. Food and Drug Administration, Apr. 6, 2017, https://www.fda.gov/media/104674/download.

[9] This estimate makes several assumptions about elasticity, consumption trends, and tax base design (on the vapor component). Estimate assumes elasticity of -0.3 for cigarettes and -0.6 for other tobacco and nicotine products, a negative consumption trend for cigarettes, and tax increases passed on to consumers.

[10] Ulrik Boesen and Tom VanAntwerp, “How Stable is Cigarette Tax Revenue?” Tax Foundation, May 3, 2021,

https://www.taxfoundation.org/cigarette-tax-revenue-tool/.

[11] U.S. Food and Drug Administration, “FDA Commits to Evidence-Based Actions Aimed at Saving Lives and Preventing Future Generations of Smokers,” Apr. 29, 2021, https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-commits-evidence-based-actions-aimed-saving-lives-and-preventing-future-generations-smokers.

[12] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “Tobacco Brand Preferences,” May 18, 2020, https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/fact_sheets/tobacco_industry/brand_preference/index.htm.

[13] Ulrik Boesen, “Massachusetts Flavored Tobacco Ban Has Severe Impact on Tax Revenue,” Tax Foundation, Jan. 19, 2021, https://www.taxfoundation.org/massachusetts-flavored-tobacco-ban/.

[14] Ulrik Boesen, “Excise Tax Application and Trends,” Tax Foundation, Mar. 16, 2021, https://www.taxfoundation.org/excise-taxes-excise-tax-trends/#Design.

[15] America’s Health Rankings, “Annual Report,” United Health Foundation, December 2020, https://www.americashealthrankings.org/explore/annual/measure/Smoking/population/Smoking_LT_25k/state/ALL.

[16] The Master Settlement Agreement refers to the settlements paid by tobacco manufacturers after the 1998 court case involving the largest tobacco manufacturers and 46 states. See Public Law Health Center, “Master Settlement Agreement,” accessed, May 24, 2021, https://www.publichealthlawcenter.org/topics/commercial-tobacco-control/commercial-tobacco-control-litigation/master-settlement-agreement.

[17] All states with a general sales tax except Oklahoma levy that tax on retail sales of cigarettes.

[18] Truth Initiative, “Why are 72% of smokers from lower-income communities?”Jan. 24, 2018,

[19] Assuming 100 percent of price increase is passed on to consumers. Calculated using data from the U.S. Census Bureau, “2019 State Government Tax Tables,” and an elasticity effect of -0.3.

[20] Joint Committee on Taxation, “The Income and Payroll TaxA payroll tax is a tax paid on the wages and salaries of employees to finance social insurance programs like Social Security, Medicare, and unemployment insurance. Payroll taxes are social insurance taxes that comprise 24.8 percent of combined federal, state, and local government revenue, the second largest source of that combined tax revenue. Offset to Changes in Excise Tax Revenues,” Dec. 23, 2011, https://www.jct.gov/publications/2011/jcx-59-11/.

[21] See generally Department of State, “The Global Illicit Trade in Tobacco: A Threat to National Security,” December 2015, https://www.2009-2017.state.gov/documents/organization/250513.pdf.

[22] Ulrik Boesen, “Cigarette Taxes and Cigarette Smuggling by State, 2018,” Tax Foundation, Nov. 24, 2020, https://www.taxfoundation.org/cigarette-taxes-cigarette-smuggling-2020/.

[23] David J. K. Balfour, DSc, Neal L. Benowitz, MD, Suzanne M. Colby, PhD, Dorothy K. Hatsukami, PhD, Harry A. Lando, PhD, Scott J. Leischow, PhD, Caryn Lerman, PhD, Robin J. Mermelstein, PhD, Raymond Niaura, PhD, Kenneth A. Perkins, PhD, Ovide F. Pomerleau, PhD, Nancy A. Rigotti, MD, Gary E. Swan, PhD, Kenneth E. Warner, PhD, and Robert West, PhD, “Balancing Consideration of the Risks and Benefits of E-Cigarettes,” American Journal of Public Health, Aug. 19, 2021, 1-12, https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2021.306416.

[24] Public Health England, “ E-cigarettes around 95% less harmful than tobacco estimates landmark review,” Aug. 19, 2015, https://www.gov.uk/government/news/e-cigarettes-around-95-less-harmful-than-tobacco-estimates-landmark-review.

[25] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “Current Cigarette Smoking Among Adults in the United States,” Nov. 18, 2019, https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/fact_sheets/adult_data/cig_smoking/index.htm.

[26] Michael F. Pesko, Charles J. Courtemanche, and Johanna Catherine Maclean, “The Effects of Traditional Cigarette and E-Cigarette Taxes on Adult Tobacco Product Use,” Journal of Risk and Uncertainty 60 (July 24, 2020), https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11166-020-09330-9.

[27] Henry Saffer, Daniel L. Dench, Michael Grossman, and Dhaval M. Dave, “E-Cigarettes and Adult Smoking: Evidence from Minnesota,” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 26589, December 2019, https://www.nber.org/papers/w26589.

[28] U.S. Food & Drug Administration, “Modified Risk Tobacco Products,” July 20, 2021, https://www.fda.gov/tobacco-products/advertising-and-promotion/modified-risk-tobacco-products.

[29] Ulrik Boesen, “Colorado Tobacco Tax Bill Includes Positive Change,” Tax Foundation, June 11, 2020, https://taxfoundation.org/colorado-tobacco-tax-bill-includes-positive-change/.

[30] Closed system: These systems are normally sold as pods or cartridges. The best-known product within the category is JUUL. Closed tank systems normally have higher nicotine levels per milliliter to allow for consuming the desired amount of nicotine in shorter sessions. Open system: A vapor product that allows the consumer to manually refill the liquid and have more freedom in voltage and nicotine levels.

[31] A pod corresponds to a pack of cigarettes; see Royal College of Physicians, “Smoking and health 2021, A Coming of Age for Tobacco Control?” May 2021, 13, https://www.rcplondon.ac.uk/projects/outputs/smoking-and-health-2021-coming-age-tobacco-control.

[32] United States Government Accountability Office, Tobacco Taxes: Market Shifts toward Lower-Taxed Products Continue to Reduce Federal Revenue, June 2019, https://www.gao.gov/assets/700/699804.pdf.

Share this article