See our updated 2021 post, Which States Are Taxing Forgiven PPP Loans?

The federal government is offering small businesses a lifeline in the form of loans that can be forgiven if they use the money for specified purposes (like payroll, rent and mortgage payments, group health benefits, and utilities) and retain their employees. The federal government will not count a fully or partially forgiven loan as taxable income. States might, unless policymakers act.

Under federal law, loan forgiveness generally counts as taxable incomeTaxable income is the amount of income subject to tax, after deductions and exemptions. Taxable income differs from—and is less than—gross income. , and states almost invariably incorporate this provision into their own codes. The Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act, however, expressly excludes the forgiveness of small business loans under the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) from this provision. Since states generally follow federal treatment of debt discharge, they would be expected to incorporate this exception as well—but only if they conform to the most recent version of the Internal Revenue Code (IRC), which includes the exception.

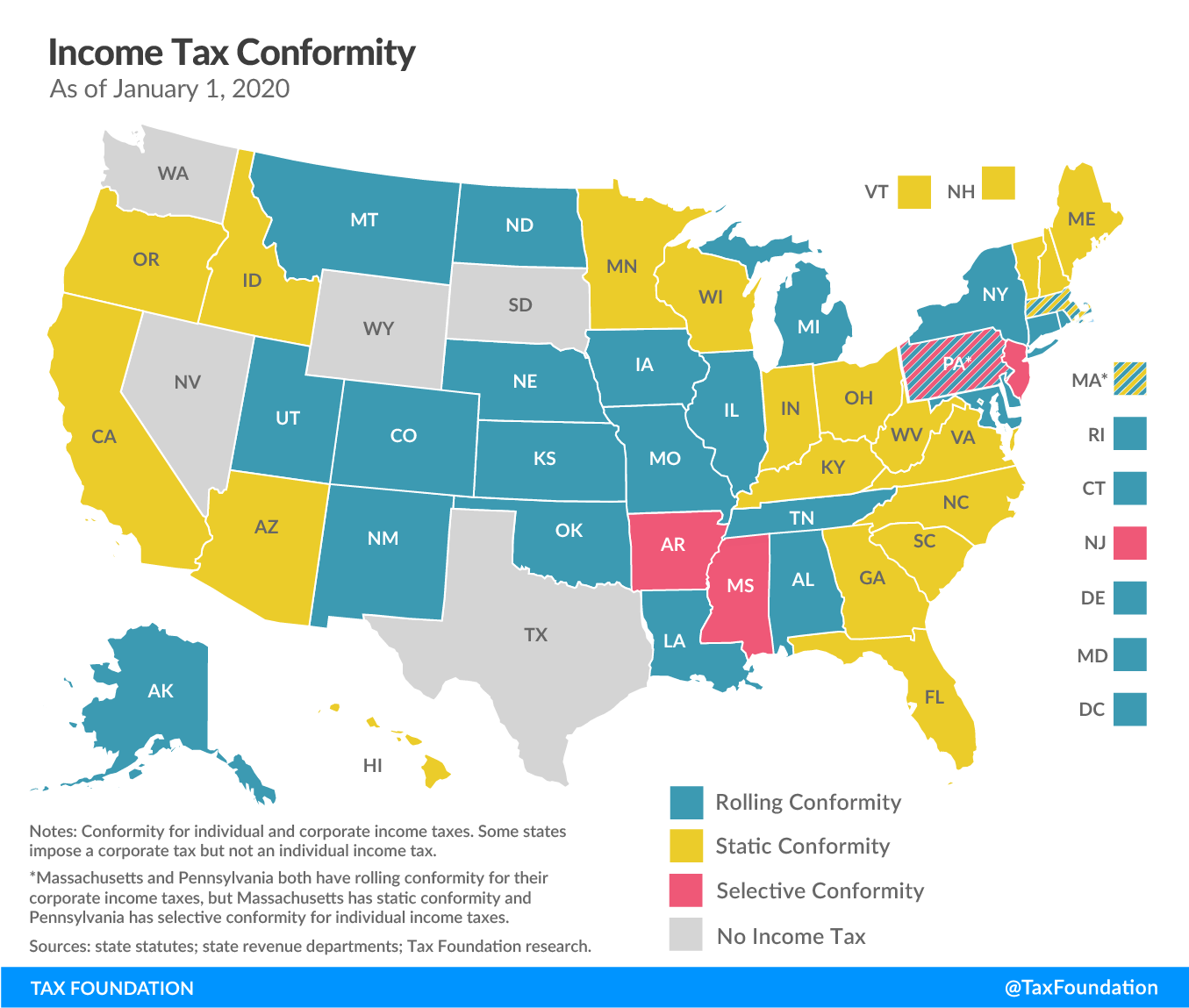

Many states have what is called static or fixed date conformity, where they include large swaths of the IRC by reference, but not as it exists right now; rather, as it existed as of some specific date, often the end of the previous calendar year. Each year, lawmakers must vote to update their conformity date—and sometimes they don’t.

States with what is known as rolling conformity are set; they will not tax the forgiveness of federal loans under the PPP unless lawmakers in those states adopt a law expressly doing so. But with static conformity states, it all depends on if and when they update their conformity.

Given early adjournments, many states are already behind. Typically, these states would use the 2020 legislative sessions to conform to the IRC as it existed at the end of the 2019 taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. year (the one on which businesses and individuals are now making final payments). In some cases, this simply didn’t happen.

Although this is less than ideal, federal tax changes between 2018 and 2019 were relatively modest. The lack of conformity increases compliance costs, since businesses and individuals must make adjustments on their state forms that effectively account for what the federal tax code looked like a year earlier. (This is much more complex for businesses than it is for individuals, particularly those with relatively straightforward tax liability.) But it becomes especially important when major changes are made to the federal tax code, as after the enactment of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) in late 2017, or now, after the tax changes in the CARES Act.

The sooner businesses know what to expect, the better, but ultimately, businesses won’t owe state taxes on forgiven PPP loans if their states conform before final calendar year 2020 tax returns are due next year. If, however, states fail to conform by then, small businesses might be left with an unexpected tax burden.

Unfortunately, a few states are notorious about not updating their conformity dates. California’s conformity date is still stuck in 2015. Wisconsin uses a 2017 conformity date. New Hampshire just brought its conformity date into the present after several years of neglect. And Massachusetts’ individual (but not corporate) income tax still uses the IRC as it existed in 2005. It’s not uncommon for states to fall a year or two behind—but this year it matters, for PPP loans and other provisions related to the CARES Act.

If states fail to update their conformity date to a date after the implementation of the CARES Act or otherwise make express provision for its exclusion from the tax base, they will wind up taxing this federal lifeline to small businesses. Most probably do not intend to do so; many may be entirely unaware of the potential. But it’s an important reason for states not to lose sight of the importance of keeping their IRC conformity up-to-date, or better yet, joining the 21 states (and the District of Columbia) with rolling conformity for both individual and corporate income taxes.

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

Subscribe