A constitutional amendment (ACA-22) pending before the California Assembly would more than double the state’s corporate income taxA corporate income tax (CIT) is levied by federal and state governments on business profits. Many companies are not subject to the CIT because they are taxed as pass-through businesses, with income reportable under the individual income tax. rate, yielding the nation’s highest rate–an astonishing 18.84 percent, up from the current rate of 8.84 percent. Assemblyman Kevin McCarty (D), one of the lead sponsors of the amendment, characterized it as “middle class taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. justice” and argued that given federal rate reductions, corporations could afford to pay more in California taxes.

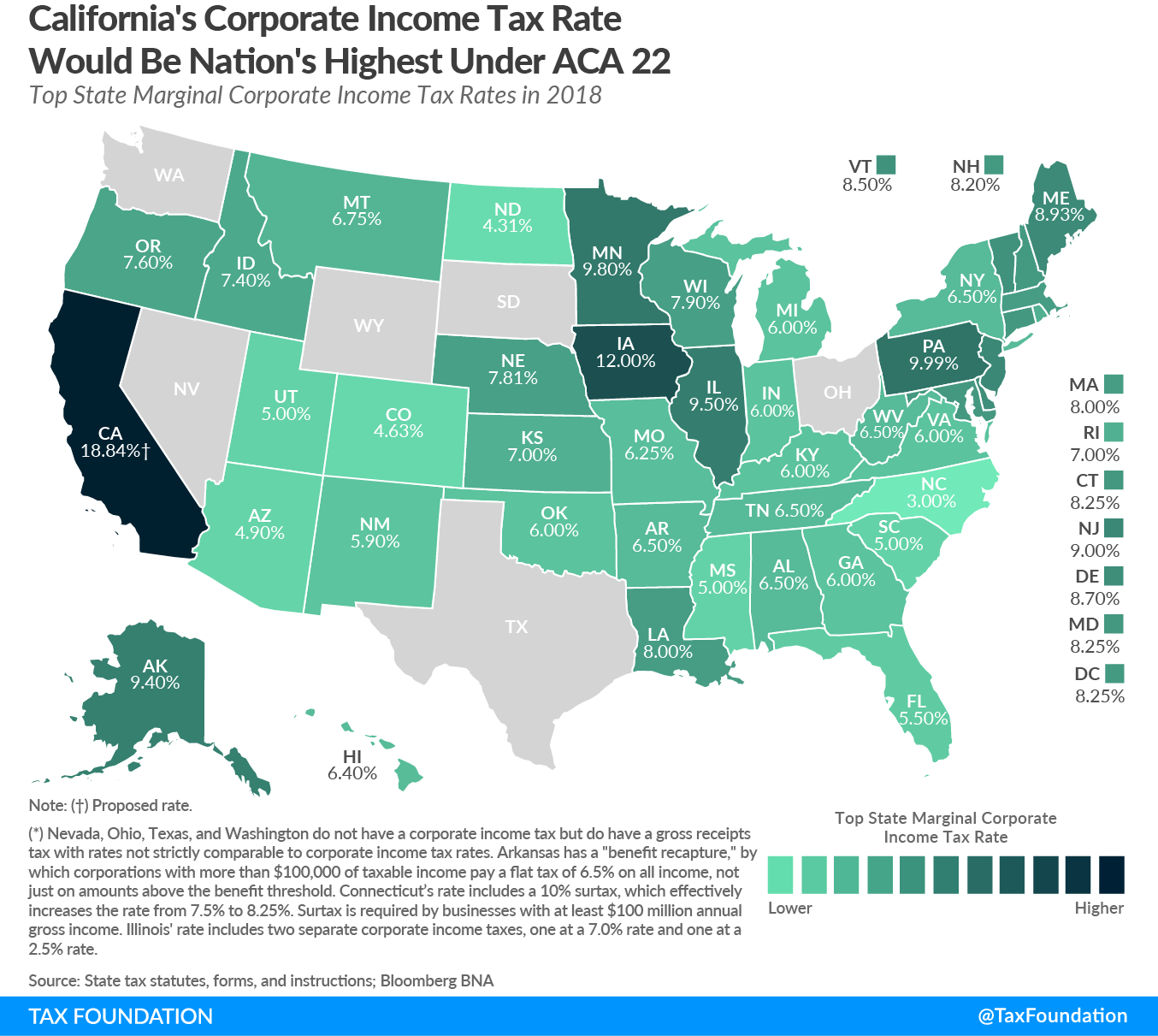

A lot more, evidently: the new top marginal corporate rate in California, imposed on all business income above $1 million, would be 90 percent of the federal rate of 21 percent. Nationally, the average top marginal corporate income tax rate is currently 6.5 percent, and the median is 6.3 percent. The proposed California rate would be three times the current median rate.

Only one rate currently hits double digits, and that’s Iowa’s 12 percent corporate rate, which is partly ameliorated by a deduction worth 50 percent of federal taxes paid. The second-highest rate is Pennsylvania’s 9.99 percent—and again, California is contemplating a rate of 18.84 percent.

The recent federal rate reduction, from 35 to 21 percent, brings the U.S. corporate income tax rate in line with the average rate among developed nations. The lower rate not only makes the U.S. a more attractive destination for corporate investment, but also expands the overall scope of investment opportunities, since lower costs (including tax costs) mean that a greater number of projects will be viable.

For the most part, states are now competing to secure their share of that additional investment, whether their voters and elected officials liked the overall thrust of the new tax law. Under ACA-22, California would effectively be saying “no thanks.”

Assemblyman McCarty characterizes it as simply taking back a portion of the federal cut, which is true on its own, but the result would be that California becomes markedly less competitive than its peers. With lower federal rates, the rate disparities among states suddenly take on greater significance for companies, and an 18.84 percent top corporate rate in California wouldn’t stack up very well against Oregon’s 7.6 percent or Arizona’s 4.9 percent, let alone against Nevada and Washington, both of which forgo corporate income taxes altogether. (Both, however, do impose gross receipts taxA gross receipts tax, also known as a turnover tax, is applied to a company’s gross sales, without deductions for a firm’s business expenses, like costs of goods sold and compensation. Unlike a sales tax, a gross receipts tax is assessed on businesses and apply to business-to-business transactions in addition to final consumer purchases, leading to tax pyramiding. es, which have their own set of issues.)

California’s current 8.84 percent rate hasn’t drained the state of businesses; California boasts 54 Fortune 500 companies, one of three states with 50 or more (joining New York and Texas). There are plenty of reasons why businesses might want to be located in California even though costs (taxes and otherwise) are high. Even now, however, we’re seeing an exodus toward lower-tax jurisdictions. What began as a trickle is now a steady stream. At 18.84 percent? It could be a torrent.

Governor Jerry Brown (D) has made headlines for sounding a pessimistic note in an era of economic expansion. “What’s out there is darkness, uncertainty, decline, and recessionA recession is a significant and sustained decline in the economy. Typically, a recession lasts longer than six months, but recovery from a recession can take a few years. ,” he warned legislators while presenting his budget, expressing his concern that the good times may be near an end. Even if one isn’t quite so pessimistic, it’s hard to dispute this concern: “California has a very volatile tax system. It means that money comes in very generously, very buoyantly, but it goes out the same way.”

This is true, and it’s largely because of the state’s heavy taxes on corporations and high earners. Corporate income taxes are particularly volatile. Even in a recession, most people will still earn wages and still engage in consumption, so individual income taxAn individual income tax (or personal income tax) is levied on the wages, salaries, investments, or other forms of income an individual or household earns. The U.S. imposes a progressive income tax where rates increase with income. The Federal Income Tax was established in 1913 with the ratification of the 16th Amendment. Though barely 100 years old, individual income taxes are the largest source of tax revenue in the U.S. and sales taxA sales tax is levied on retail sales of goods and services and, ideally, should apply to all final consumption with few exemptions. Many governments exempt goods like groceries; base broadening, such as including groceries, could keep rates lower. A sales tax should exempt business-to-business transactions which, when taxed, cause tax pyramiding. collections can only drop so far, but many businesses may post net losses and thus have no corporate tax liability whatsoever. Under ACA 22, California would double down on one of its most volatile revenue streams in an attempt to increase collections by $17 billion a year.

How significant is that? If collections in other states held constant, California’s new corporate income tax collections would account for more than a quarter of the total of state corporate income tax revenues nationwide. California has a lot of business activity, but not that much. And if California’s corporate tax burden nearly tripled (from about $10 billion to $27 billion a year), it stands to reason that there would be a lot less business activity to tax.

Companies make their location and investment decisions based on a variety of factors: workforce, education, quality of life, cost of living, taxes, and more. Taxes are a factor, but far from the only one. But if California’s corporate rate rivals most national rates, while other states continue to offer far more attractive tax systems, the rate rises greatly in importance. Companies willing to put up with an 8.84 percent rate because of what California has to offer might well reconsider if that rate is jacked up to 18.84 percent.

On our State Business Tax Climate Index, which measures tax structure, California would slip from 48th to a projected 49th overall were this amendment ratified, with its corporate income tax component rank plummeting from 32nd to 46th. The corporate income tax rate is only one variable of 114 in an analysis focused on a wide range of structural issues, but an 18.84 percent rate would set California so far apart that the component result is dramatic.

More important, though, is the dramatic effect on California. The Sacramento Bee’s editorial board got it right:

“[I]t is a tin-eared attempt by McCarty, D-Sacramento, and [cosponsor Phil] Ting, D-San Francisco, to resist President Donald Trump and congressional Republicans who approved a massive federal tax cut for corporations. It’s especially ill-timed when Gov. Jerry Brown anticipates sufficient tax revenue to maintain a $13.5 billion reserve fund this year.

“[…] There’s plenty broken with California’s tax structure. But its 8.84 percent corporate tax rate is already relatively high compared with other states. Bills that blindly seek to soak big business and the rich at a time of budget surplus solve nothing.”

Errata: An earlier version of those post stated that Pennsylvania’s 9.99 percent corporate net income tax was higher than Iowa’s 12 percent corporate income tax after accounting for Iowa’s partial federal deductibility. This was in error, though other elements of Pennsylvania’s corporate code (particularly the state’s newly adverse treatment of capital investment) may result in a higher effective rate in Pennsylvania.