Last week, Senator Ron Wyden (D-OR) introduced the “Providing Real Opportunities for Growth to Rising Entrepreneurs for Sustained Success” (PROGRESS) Act, which contains two new tax credits intended to increase investment in smaller businesses and help them grow. However, the legislation may incentivize firms to remain below the tax credit eligibility threshold, make the taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. code less neutral, shift net investment away from slightly larger firms, and slow firm growth.

Plan Structure

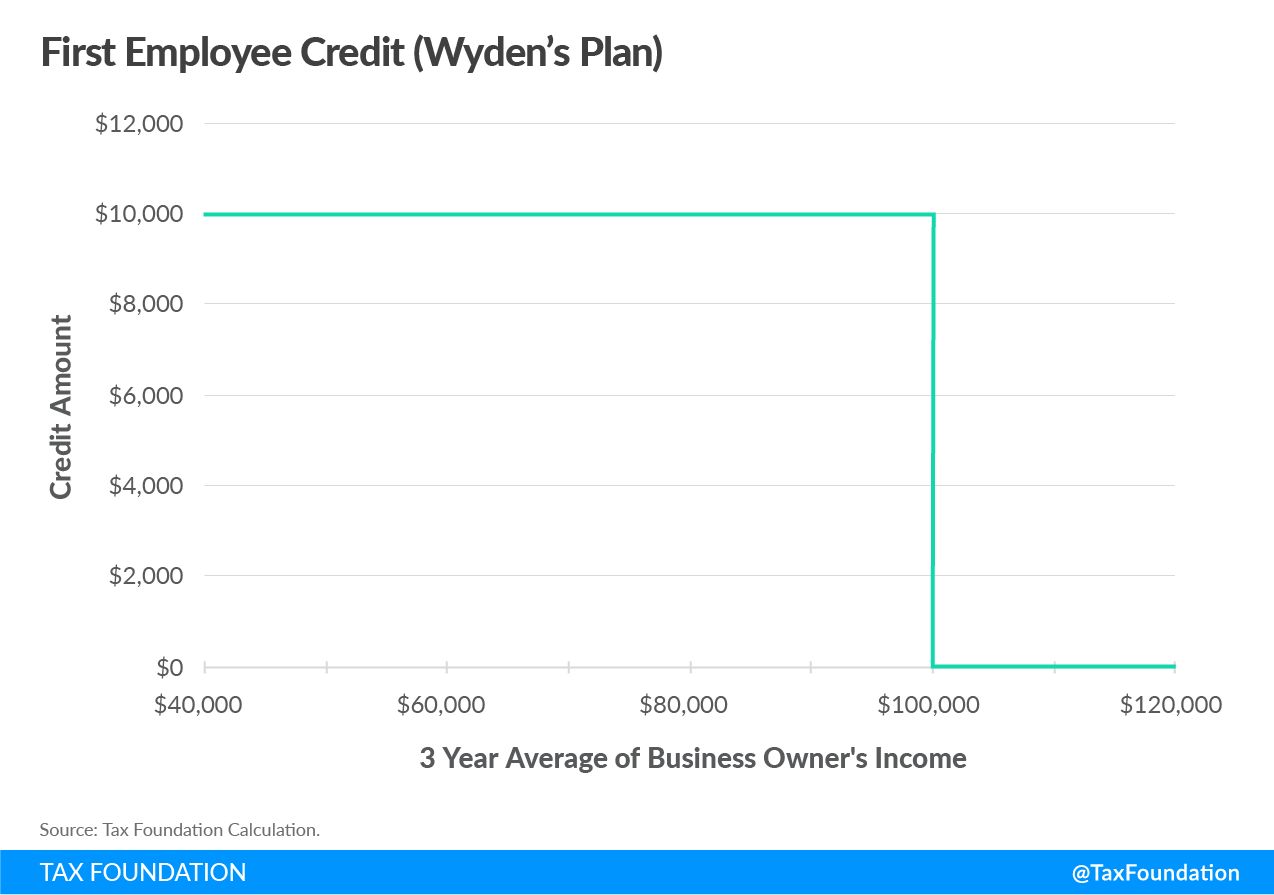

The “first employee credit” would allow certain small businesses owned by individuals earning less than an average of $100,000 ($200,000 filing jointly) over the last three years to claim a 25 percent credit against their income or payroll tax liability on all eligible W-2 wage expenses. The credit amount would be limited to $10,000 in a single tax year, with a lifetime limit of $40,000. Qualified businesses may also apply the tax creditA tax credit is a provision that reduces a taxpayer’s final tax bill, dollar-for-dollar. A tax credit differs from deductions and exemptions, which reduce taxable income rather than the taxpayer’s tax bill directly. against employer-side payroll taxA payroll tax is a tax paid on the wages and salaries of employees to finance social insurance programs like Social Security, Medicare, and unemployment insurance. Payroll taxes are social insurance taxes that comprise 24.8 percent of combined federal, state, and local government revenue, the second largest source of that combined tax revenue. liability if the firm lacks taxable income.

The PROGRESS Act also includes an “investor credit” against an investor’s income tax liability equal to 50 percent of a qualified investment, limited to 10 percent in a single tax year and a lifetime credit limitation of $50,000.[1] Small businesses eligible for investment must also have majority owners earning less than an average of $100,000 ($200,000 filing jointly) over the last three years. Additionally, if a business takes the employee credit, the business cannot also deduct the claimed wages for income tax. Otherwise, businesses would receive two tax benefits from the same wages.

Tax credits reduce tax liability dollar-for-dollar (while deductions reduce taxable incomeTaxable income is the amount of income subject to tax, after deductions and exemptions. Taxable income differs from—and is less than—gross income. ). Refundable tax credits allow taxpayers to receive a benefit if the credit amount exceeds their tax liability. By contrast, nonrefundable credits reduce taxable liability until the liability reaches zero. The bill limits the first employee credit and the investor credit in scope and eligibility. For example, the first employee credit is not refundable if the claimed credit exceeds payroll tax liability.

For businesses, tax credits are more valuable than equivalent deductions, since they reduce what the business owes overall rather than reducing income subject to a firm’s marginal income tax rate. Hence, a business eligible for the credit would need to determine whether, in its specific circumstances, the proposed credit or the existing deduction is more valuable.

Watch out for that Cliff

The first employee credit contains a tax cliff on firms which earn more than an average of $100,000 over the last three years. Because the credit lacks any phaseout beyond $100,000, firms just above the threshold are not eligible for any part of the credit. In effect, firms under the threshold are disincentivized from earning income above $100,000, since each dollar would be subject to higher marginal tax rates. Additionally, firms above the threshold do not qualify for any of the tax benefits provided in the legislation. To illustrate, imagine a firm which claims the maximum credit of $10,000 on all eligible W-2 wages as its gross incomeFor individuals, gross income is the total of all income received from any source before taxes or deductions. It includes wages, salaries, tips, interest, dividends, capital gains, rental income, alimony, pensions, and other forms of income. For businesses, gross income (or gross profit) is the sum of total receipts or sales minus the cost of goods sold (COGS)—the direct costs of producing goods, including inventory and certain labor costs. reaches $40,000 (Figure 1). Once the firm’s gross revenue exceeds $100,000, it receives no benefit for each dollar earned. Moreover, the credit creates uncertainty as to whether an individual year’s earnings will impact the trailing three-year average.

The proposal could be improved by creating a credit phaseout period so that the size of the tax credit gradually decreases as income increases beyond $100,000. Including a phaseout would increase the credit’s cost in forgone revenue but reduce the distortions created by the eligibility cliff. A phaseout makes the credit available for firms above the threshold, reduces the marginal tax rateThe marginal tax rate is the amount of additional tax paid for every additional dollar earned as income. The average tax rate is the total tax paid divided by total income earned. A 10 percent marginal tax rate means that 10 cents of every next dollar earned would be taken as tax. for firms at the threshold, and makes the tax code more neutral with respect to the benefit. However, a phaseout would increase the marginal tax rate on losing the benefit throughout the phaseout. Thus, the phaseout effectively “spreads out” the cliff over a range of income.

The investor credit also creates a tax cliff. By limiting the credit’s eligibility to small firms, the policy encourages a shift from investment in small firms just over the threshold to smaller firms just under the threshold. It is possible that net investment would not increase but merely shift between similarly sized firms whose assets fall near the threshold. Further, the credit structure violates economic neutrality by treating small firms more favorably than medium or large-sized firms. Ideally, the tax code should treat businesses and income consistently rather than giving preferential tax treatment to smaller firms.

On net, the total amount of investment may not grow but instead be redirected. To improve the proposal, the investor credit could be phased out, reducing the tax cliff but leaving the shifting investment effects unaddressed.

Conclusion

Senator Wyden’s proposal seeks to aid smaller firms by providing new tax credits for employee wages paid and investment contributions. However, the legislation includes significant tax cliffs which may redirect and reduce investment in small to medium-sized firms as taxpayers respond to incentives. Policymakers could look at other tax proposals to assist small firms while preserving neutral tax treatment of businesses regardless of size.

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

Subscribe[1] All credit amounts are indexed to inflationInflation is when the general price of goods and services increases across the economy, reducing the purchasing power of a currency and the value of certain assets. The same paycheck covers less goods, services, and bills. It is sometimes referred to as a “hidden tax,” as it leaves taxpayers less well-off due to higher costs and “bracket creep,” while increasing the government’s spending power. .

Share this article