One of the inviolate principles of good tax policy is permanence. In order for taxpayers to properly comply with the tax code, and plan their personal and business decisions around it, they must know that the tax system will not be subject to frequent changes. Thus, lawmakers have an obligation to make tax policies as permanent as possible and avoid arbitrary sunsets or retroactive provisions.

Sadly, what is good in theory is not always feasible in practice. Senate lawmakers faced a dilemma in having to balance the multiple goals of crafting a tax reform plan that maximized economic growth, delivered middle-class tax cuts, and comported with an internal Senate rule, the Byrd Rule. This rule, named after the late West Virginia Senator Robert Byrd, prohibits tax and spending bills from increasing the federal deficit beyond the ten-year budget window.

The Byrd Rule is intended to prevent budget gimmicks that circumvent the budget resolutions by back-loading tax cuts so that they may meet the ten-year revenue mandates in the budget resolutions but deliver big tax cuts later. Unfortunately, the effect of the Byrd Rule is to make many permanent tax changes difficult to enact.

To comply with the Byrd Rule, the Finance Committee faced a choice: It could sunset all or some of the tax cuts at the end of ten years, in the same way that the 2001 and 2003 tax cuts were designed to expire in 2011 and 2013, or offset those future tax cuts by raising other taxes or closing additional loopholes.

None of these options are optimal. The first option violates the principle of tax permanence, while the second option has the potential of undermining the economic growth that the tax bill is attempting to achieve. So on what basis should lawmakers make this decision?

The Finance Committee made the right decision in choosing the economy over optics and politics. The Chairman’s Mark makes the corporate rate cut and the international provisions permanent, but sunsets most the individual provisions in 2025, thus giving the public the impression the Committee favors big business over regular taxpayers.

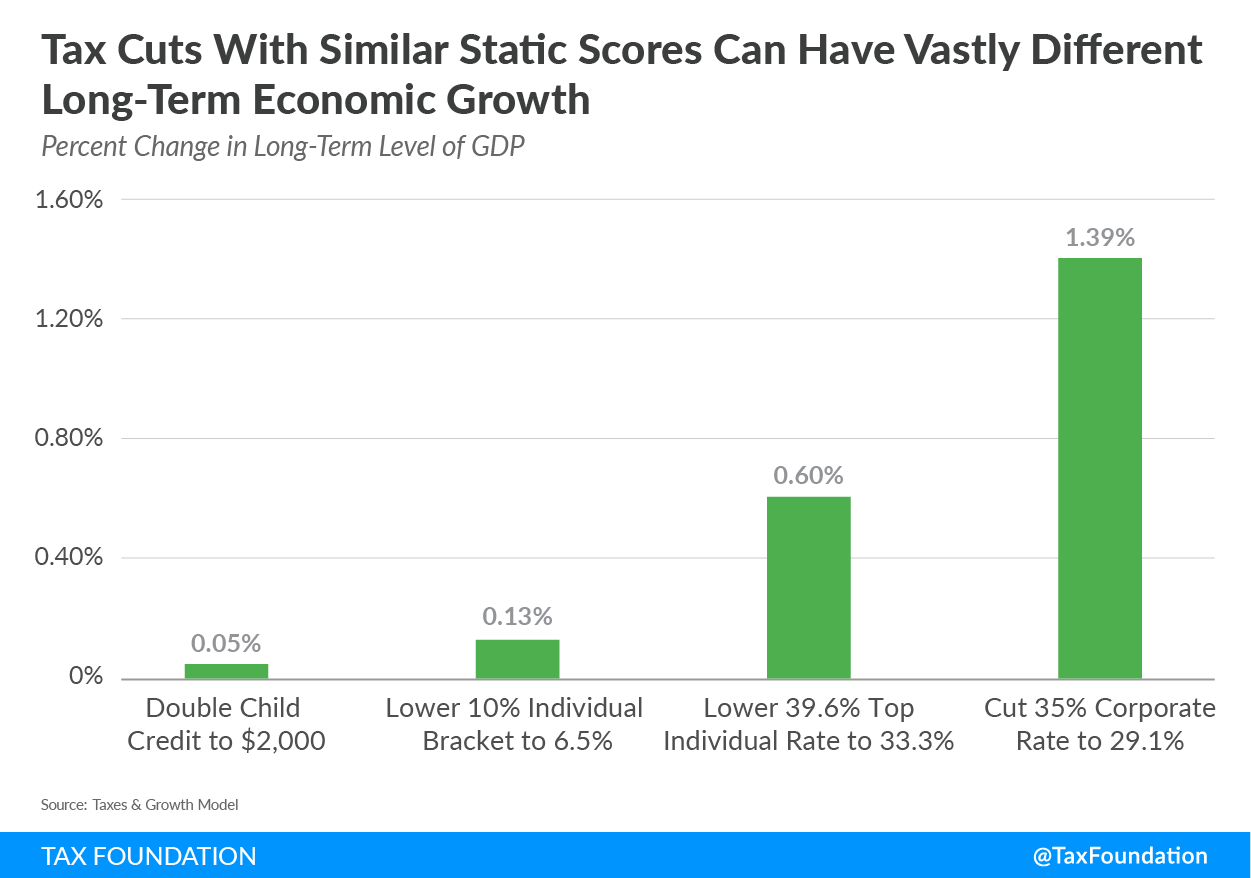

But this illustrates the paradox of tax reform. As we can see in the chart below, the tax policies that do most for economic growth—such as the corporate rate cut—are the least politically popular, while the tax cuts that do less for growth—child tax credits and individual rate cuts—are the most politically popular.

The chart shows the results of a thought experiment in which Tax Foundation economists used our Taxes and Growth (TAG) Macroeconomic Tax Model to measure the growth effects of four tax policies with the same static revenue loss. Doubling the child credit to $2,000 produces the least amount of growth because it does the least to incentivize people to work, save, and invest. Cutting the lowest individual tax bracket produces a bit more growth, but because it benefits taxpayers at every income level its marginal effect on work incentives are minimal.

Of the individual tax cuts in this exercise, cutting the top marginal rate produces the most growth because it does impact work, investment, and savings decisions at the margin—especially for taxpayers with business income. By contrast, cutting the corporate tax rate produces many times the growth, because it lowers the cost of capital which, in turn, leads to higher capital investment and higher GDP.

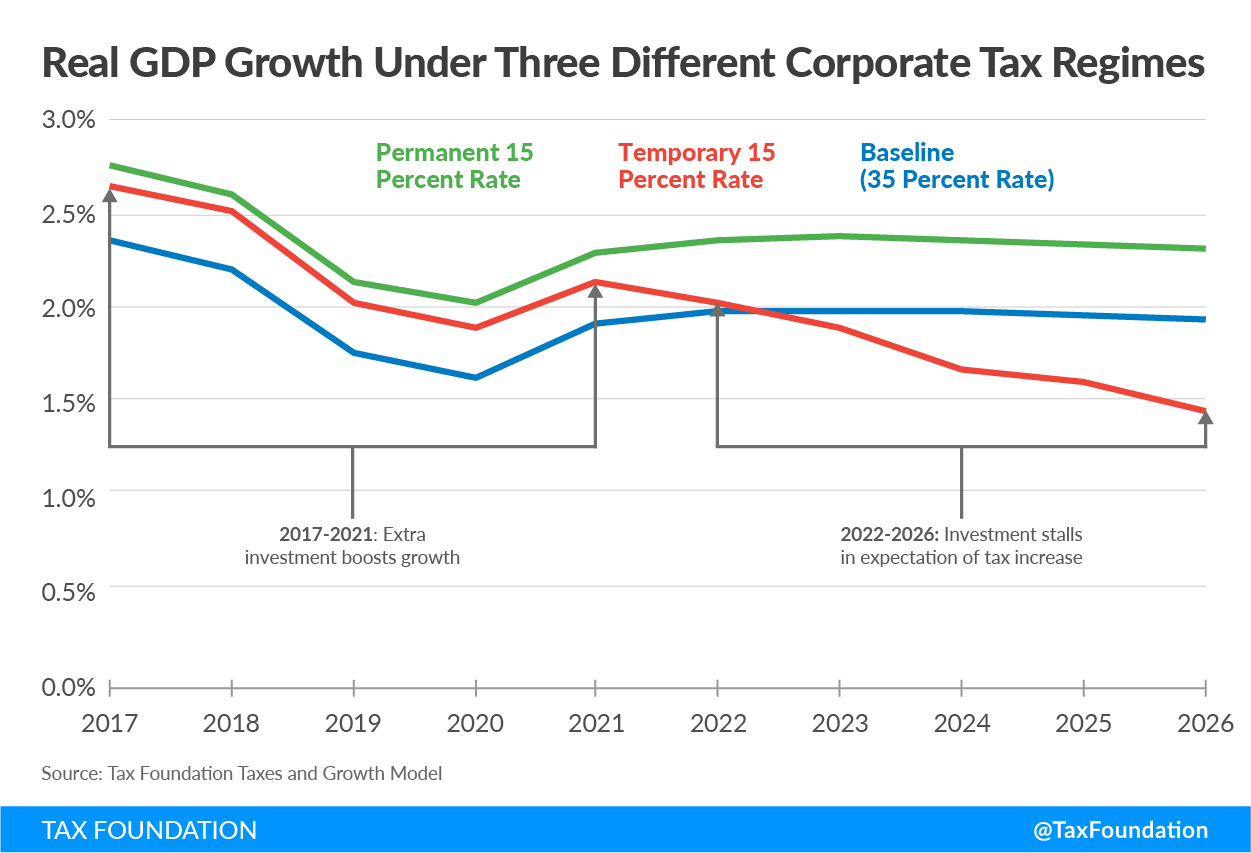

However, the growth impact of a corporate rate cut only occurs if the policy is permanent. Tax Foundation economists also simulated the effects of a temporary corporate rate cut to 15 percent compared to the effects of a permanent rate cut, and the baseline estimates under current law. The results are shown in the nearby chart.

A permanent corporate rate reduction reduces the cost of capital and makes new investments worthwhile that otherwise would not have been. Under estimates from the TAG model from earlier this year, a permanent cut to 15 percent would boost investment substantially, which allows a sustained period of higher growth. Such a policy adds about 0.39 percentage points to GDP growth per year over a decade, eventually resulting in a GDP that is 3.9 percent larger than the baseline scenario after ten years. This additional 3.9 percent level adjustment to GDP remains for as long as the policy stays in effect; more investments are profitable, and therefore, the nation is richer.

A temporary corporate rate reduction looks similar at first: it initially produces more investment and growth. However, the effect is never as strong as for the permanent cut. Worse, the improvements to growth fade considerably. The increase in GDP peaks in the sixth year, with a grand total of 1.37 percent added to GDP over all six years. Then, growth from the seventh year on is actually slower than it would have been with no tax cut at all. By the end of the tenth year and the sunset of the policy, GDP is only 0.14 percent larger than it would have been without the tax cut.

These estimates are a bit out of date; the latest version of the TAG model now finds a slightly smaller economic effect from lowering the corporate rate. However, the relative magnitudes are the real story here: cutting the corporate tax rate on a temporary basis does not produced lasting economic benefits, like a permanent rate cut would.

The lesson is very clear: the only way to boost the economy for the long term is to make the business tax reforms permanent.

Permanence is somewhat less critical on the individual nonbusiness side of the code, where wages are the largest component of income. Decisions on hours worked are made on short time horizons. There is relatively little economic damage from turning the ordinary tax rates, brackets, and the standard deductions into annual “extenders.” Assuming Congress intends them to be permanent, it can extend them periodically for a year or two at a time, or whenever a strong 60-vote majority can support a permanent extension under normal order.

The one exception to this is the provision in the Chairman’s Mark that sunsets the 17.4 percent deduction for pass-through business income. The economic benefits of that provision will taper off as the expiration date nears.

Permanence should be the goal of any tax reform plan. People need to have some certainty about taxes as they make economic decisions. This is especially important in planning business investment decisions, where actions today affect income over many years. Uncertainty about business taxes can make or break plans to expand factories, farms, rails lines, and mines, or develop commercial and residential real estate.

Permanence is also critical for reform of the international tax area, where firms must decide where to build production facilities, how to structure their global businesses, and where to register intellectual property. These are tax rules and business decisions that cannot readily be reversed.

Like it or not, the Byrd Rule is one of the key factors in shaping how Senators are constructing their tax reform plan. And, although the Rule was intended to prevent gimmickry, it is having the unintended consequence of pitting good tax policy against good economics. Given these choices, the Finance Committee was right to make the most pro-growth policies permanent, and sunset the ones that will do less economic harm if they need to be renewed in a few years.

Share this article