This week, the Congressional Research Service (CRS) released a report on preliminary observations of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA). The report provides a broad overview of many of the effects on the economy that one could expect from the TCJA regarding output (GDP), investment, federal revenues, effective taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. rates, wages, repatriationRepatriation is the process by which multinational companies bring overseas earnings back to the home country. Prior to the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), the US tax code created major disincentives for US companies to repatriate their earnings. Changes from the TCJA eliminate these disincentives. , international capital flows, and the incentive for corporations to invert. It analyzes each of these effects with economic data and evaluates whether the TCJA has met expectations.

Ultimately, the report concludes that there isn’t much evidence that the law has had a significant effect on the economy so far. Unsurprisingly, the report has garnered a lot of attention, especially from those who are already skeptical of the TCJA. It is seen as further evidence that the law has not lived up to its expectations.

While some will find the report’s arguments striking, many of the conclusions are not that different than those already reached by other organizations, including the Tax Foundation. The TCJA was expected to be a large tax cut with modest effects on the economy, especially in the first year. Some conclusions in the report, however, imply a more pessimistic assessment of the law’s effect on the economy than what other groups have projected. For one, the report argues that there were small (or no) first-year growth effects. However, the evidence for these conclusions is not particularly strong.

What We Already Knew

Although the report comes to stronger conclusions than it probably should, much of its arguments are very similar to what many groups have been making and match up with many existing projections—including those made by the Tax Foundation.

The report shows that federal revenues declined in 2018, relative to what revenues would have been in the absence of the TCJA, and that the decline is very close to what the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projected. A loss in revenue, especially in the first year, is not surprising. The size of the tax cut in 2018 was significant. In addition, the dynamic effects were expected to be modest in the first year. In fact, the Tax Foundation estimated the federal revenue would fall by more than $200 billion after accounting for a slightly larger economy in 2018.

The report also argues that economic data doesn’t indicate that there has been a surge in wages immediately following the TCJA. This is not surprising either. The way in which the law is projected to increase wages is through an increase in productivity through “capital deepening,” or an increase in the U.S. capital stock per worker. This effect takes time because the adjustment in the capital stock isn’t instant, nor is the bidding process that pushes up wages.

The report also argues that the bonuses that followed the passage of the TCJA were not significant and most of the cash went back to shareholders in the form of buybacks. This also makes sense. There was a good theoretical reason to think the windfall from repatriation and the tax cut on old capital would flow primarily to shareholders through buybacks over workers. As the report states, workers are paid their marginal product. Without immediate changes to worker productivity, one should not expect a corporate tax cut would go to workers. Rather, many bonus announcements may have been efforts to improve public relations, or ways to time deductions in order to maximize tax savings.

Some Weaker Evidence on Output and Investment

Where the report seems to diverge with many mainstream projections is in its conclusion that the TCJA has produced little to no increase in output (GDP) and its argument that investment has not increased as was expected. However, these conclusions are too strong given the evidence.

The first section of the report deals with the TCJA’s effect on output and investment. Overall, the piece argues that 2018 data from the Bureau of Economic Analysis’s National Income and Product Accounts (NIPA) show that the TCJA has probably had a “relatively small (if any) first-year effect on the economy.” It also states that the economy probably grew much less than most groups projected.

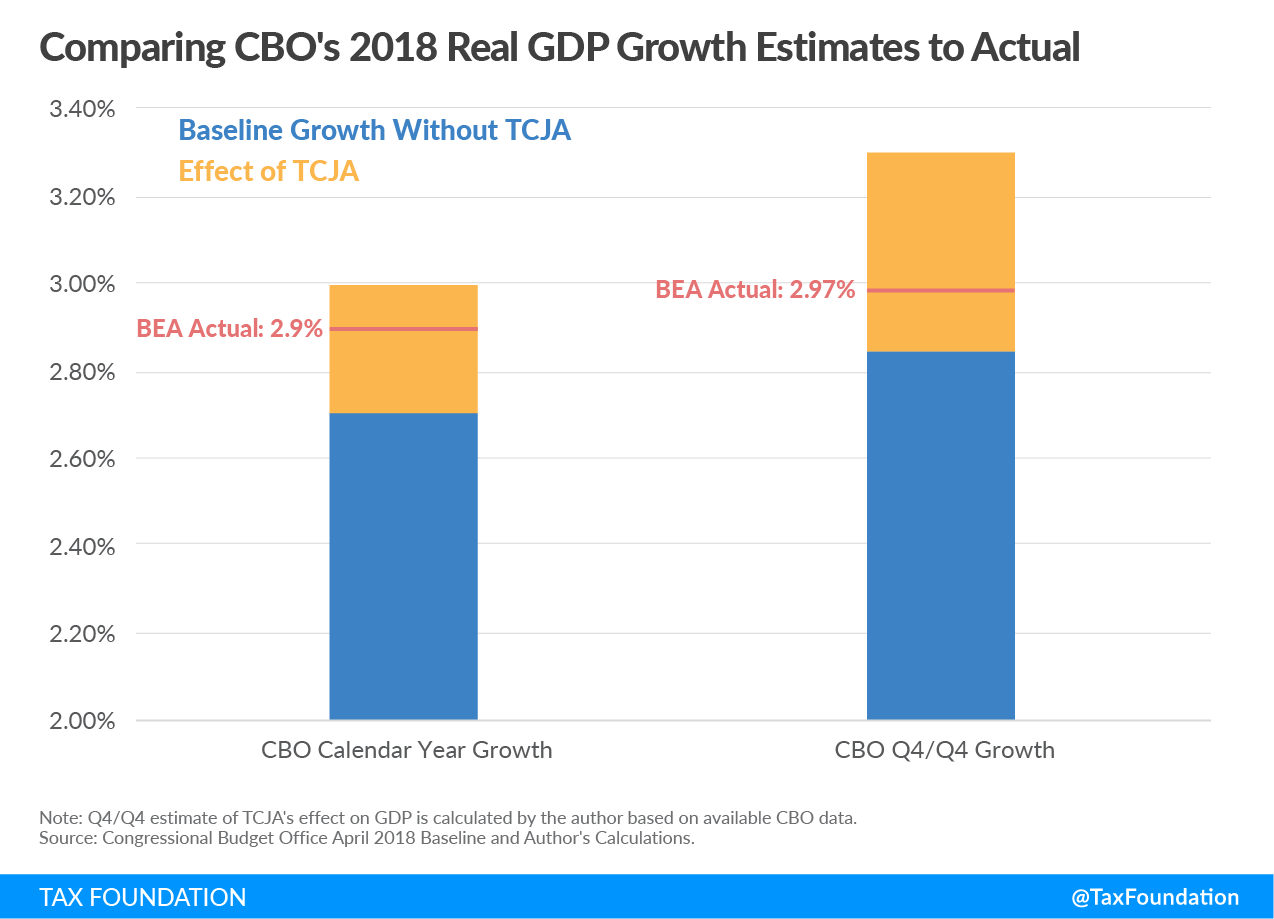

It makes this argument by comparing the CBO’s projection of growth in real GDP from Q4 2017 to Q4 2018 of 3.3 percent to NIPA’s calendar-year real GDP growth of 2.9 percent. Given that the CBO projected that 0.3 percent of GDP growth in 2018 would be due to the tax law, this implies that growth without the tax law would be 3 percent. As such, output undershot projections, which suggests the tax law had little to no effect in 2018.

However, it appears that CRS mixed up CBO projections in its analysis. CBO’s +0.3 percent growth estimate for 2018 is a calendar-year estimate (the average over all four quarters of 2018), not a Q4/Q4 estimate. CBO’s calendar-year estimate for 2018 was 3 percent (Page 10). This implies that without the tax law, GDP growth over this period would have been 2.7 percent, not 3 percent as the report states. This suggests CBO was only off by 0.1 percent and that growth was close to projections (Figure 1).

CBO didn’t produce a Q4/Q4 TCJA projection for 2018, but by extrapolating between CBO’s 2018 and 2019 TCJA projections (+0.3 and +0.6) (Page 115), the growth projection could be around 0.45 percent in Q4 of 2018. This implies a 2018 Q4/Q4 growth of 2.85 percent without the TCJA (3.3 percent minus 0.45 percent). According to BEA’s NIPA, actual 2018 Q4/Q4 growth was 2.97 percent. Looking at Q4/Q4 growth also implies CBO was off in its projection, but growth still ended up higher than CBO’s implied baseline without the TCJA.

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

SubscribeIn addition, the CRS report states that investment did increase after the passage of the TCJA. However, it argued, the increased investment did not reflect the incentive effects present in the law, calling into question whether there is much of a supply-side effect. According to the report, the U.S. economy did experience growth in Intellectual Property (IP, 7.7 percent), equipment (7.5 percent), and structures (5 percent) in 2018. However, the report argues that you should expect investment in IP to fall, not increase, and that investment in structures should increase more than equipment.

The report comes to this conclusion by calculating the change in the user cost of capital for each asset. The user cost of capital is the required gross return necessary to provide a fixed return to savers, after covering both taxes and depreciationDepreciation is a measurement of the “useful life” of a business asset, such as machinery or a factory, to determine the multiyear period over which the cost of that asset can be deducted from taxable income. Instead of allowing businesses to deduct the cost of investments immediately (i.e., full expensing), depreciation requires deductions to be taken over time, reducing their value and discouraging investment. . It finds that structures saw the largest reduction in the cost of capital, followed by equipment. It also argues that IP saw an increase in its user cost.

While investment growth doesn’t line up well with CRS’s calculation of the incentive effects of the law, investment seems to line up better with CBO’s estimates of the incentive effects (Table 1). CBO calculates the effective marginal tax rate (METR) for each type of asset in its baseline under current law and prior law. A METR measures the tax burden on marginal investment, or those that breakeven in present value. It is a measure of the incentive effect of tax policy on investment decisions. In contrast with CRS, it found that equipment saw the largest reduction in the METR, followed by IP, then buildings.

If you were to convert the CBO’s METRs into service prices, structures would still see the largest percentage reduction, followed by equipment. However, the big difference is that CBO’s estimates of the METR imply a reduction in the service price for intellectual property. As such, it would be less surprising that IP investment increased.

| Equipment | Structures (Excluding Residential Property) | Intellectual Property | Homeowner Occupied Housing | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Source: CBO April 2018 Baseline and Bureau of Economic Analysis NIPA Table 1.1.6. | ||||

|

Prior Law Marginal Tax Rate |

13.42% | 25.66% | -1.98% | -2.37% |

|

Current Law Marginal Tax Rate |

5.25% | 20.77% | -7.64% | 6.78% |

|

Difference |

-8.2% | -4.9% | -5.7% | 9.2% |

|

2018 Real Investment Growth |

7.5% | 5.0% | 7.7% | -0.3% |

It is also worth noting that the CBO calculated the METR for homeowner occupied housing. This type of investment saw a large increase in its effective tax rate. Consequently, the U.S. economy experienced a 0.3 percent decline in residential structure investment in 2018.

Lastly, it is possible that the law does produce more-than-expected investment in equipment and intellectual property in the first few years of the law. This is because the tax treatment for these assets are set to change (and more so than the treatment of buildings). After 2022, 100 percent bonus depreciation is set to phase down and ultimately expire. And after 2021, research and development will need to be amortized over five years instead of expensed. The result is that both assets will experience a tax increase. Thus, the incentive is for companies to invest more than usually before 2022 and 2023 before the tax increases apply.

Is Any Macro Data Convincing?

More generally, looking at data on economic aggregates is not particularly helpful in causal analysis. Just because the economy grew at 2.9 percent and investment in IP grew at 7.7 percent in 2018, doesn’t mean any specific policy is responsible. We don’t really know what the economy would look like in another universe in which everything is the same but we had not enacted the TCJA. Other policies that could affect the economy, such as tariffs, make causal analysis difficult.

Sometimes the best we have is CBO’s baseline projections to compare to, but even those are imperfect. CBO uses a model to estimate what it thinks the economy will look like over the next decade given current law and other factors. And while the CBO does a great job, things can change in as little as one year from when they make their projections. As a result, the baseline may not actually reflect what the world would have looked like under an alternate policy regime.

Overall, the CRS report does provide a good overview of many of the ways in which analysts believed the TCJA would impact the economy. Some of its conclusions are similar to those that others have made about the law, including the Tax Foundation. However, some conclusions the report made are too strong given available evidence.

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

Subscribe