The United Kingdom has been cited as an example of a country that has cut its corporate tax rate, but has not lost any revenue: a corporate cut that “paid for itself.” Some have argued that this should inform the U.S. taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. reform debate. Specifically, corporate tax reform efforts in the United States shouldn’t try to offset any potential corporate tax cut with base broadening.

It is true that the UK didn’t lose revenue after significantly cutting its corporate tax rate. However, it’s not true that those rate cuts were self-financing. The UK broadened the corporate tax base, which offset potential revenue loss from the rate cut.

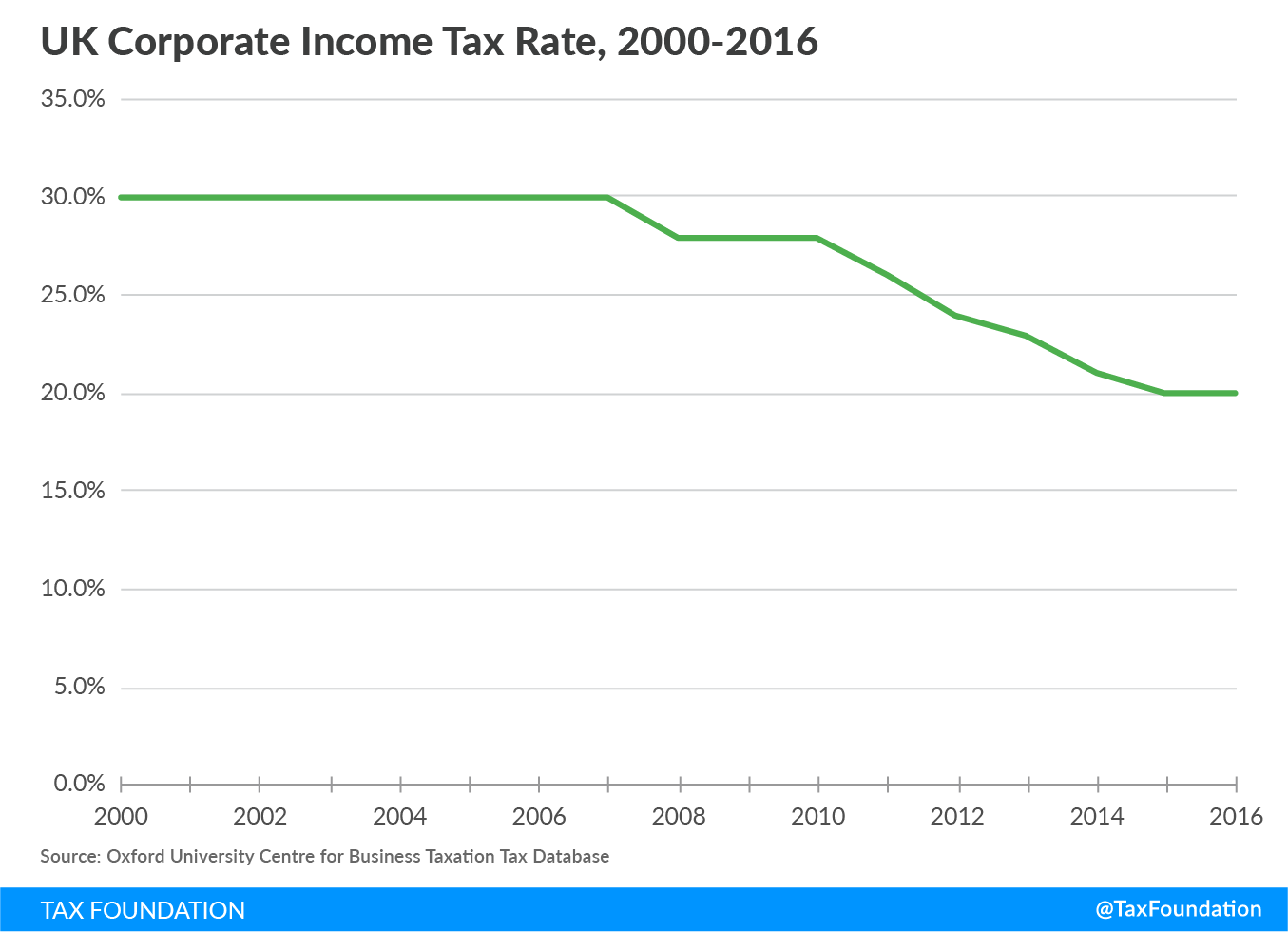

In the late 2000s and into the 2010s, the United Kingdom enacted a number of corporate tax cuts. It cut its corporate income taxA corporate income tax (CIT) is levied by federal and state governments on business profits. Many companies are not subject to the CIT because they are taxed as pass-through businesses, with income reportable under the individual income tax. several times, moved to a territorial tax systemTerritorial taxation is a system that excludes foreign earnings from a country’s domestic tax base. This is common throughout the world and is the opposite of worldwide taxation, where foreign earnings are included in the domestic tax base. , which exempts foreign corporate income from domestic taxation, and enacted a “patent boxA patent box—also referred to as intellectual property (IP) regime—taxes business income earned from IP at a rate below the statutory corporate income tax rate, aiming to encourage local research and development. Many patent boxes around the world have undergone substantial reforms due to profit shifting concerns. ,” which provides a special lower rate on profits attributable to intellectual property. The corporate rate cut was significant. The chart below show that the rate fell from 30 percent in 2007 to 20 percent in 2016 according to Oxford University Centre for Business Taxation’s Tax Database.

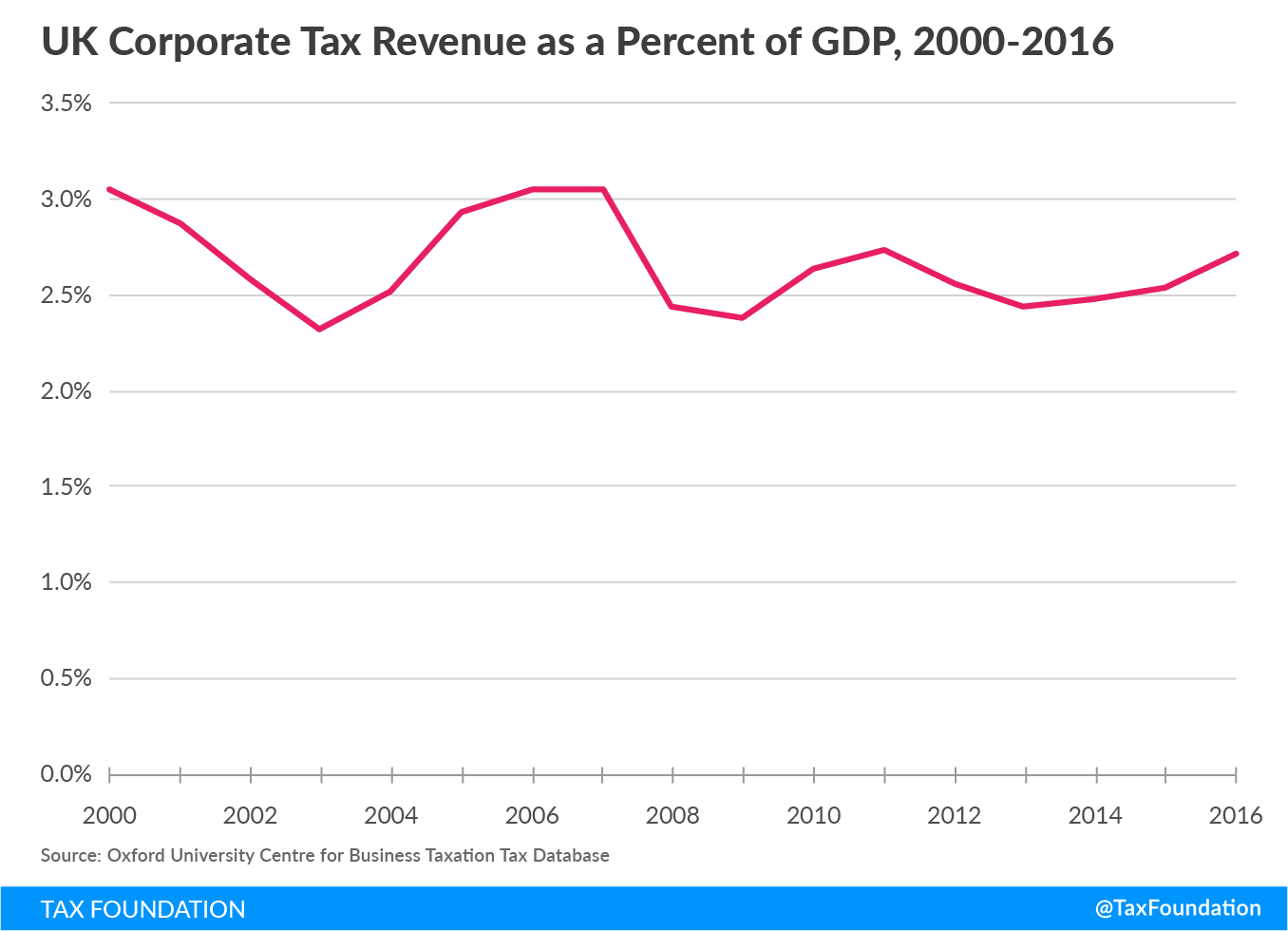

While the corporate rate fell, corporate tax revenues did not. Per data from Her Majesty’s Revenue & Customs (UK’s Treasury Department), corporate tax revenues in the United Kingdom have hovered between a little more than 3 percent of GDP and 2.4 percent of GDP. The most notable period is between 2008 and 2016. After an initial decline in revenue in 2008, revenues were relatively constant at around 2.5 percent of GDP, climbing to 2.7 percent of GDP in 2016.

This simple comparison shows why some believe that the UK’s corporate tax cut was self-financing. The lower corporate tax and the shift to a territorial tax system made the UK so attractive that corporate profits flooded back to the UK. The expanded base of taxable corporate profits made up for the lower rate, leaving revenues relatively unchanged.

It is true that corporate revenues in the United Kingdom were relatively stable after it cut its corporate tax rate and corporate revenues were higher than expected. However, there were other reforms that offset the corporate tax cuts. Chiefly, the United Kingdom made legislative changes that broadened the corporate tax base over the same period. The reform lengthened asset lives for capital investments and enacted anti-base erosion provisions. These changes ultimately helped pay for the corporate rate reduction.

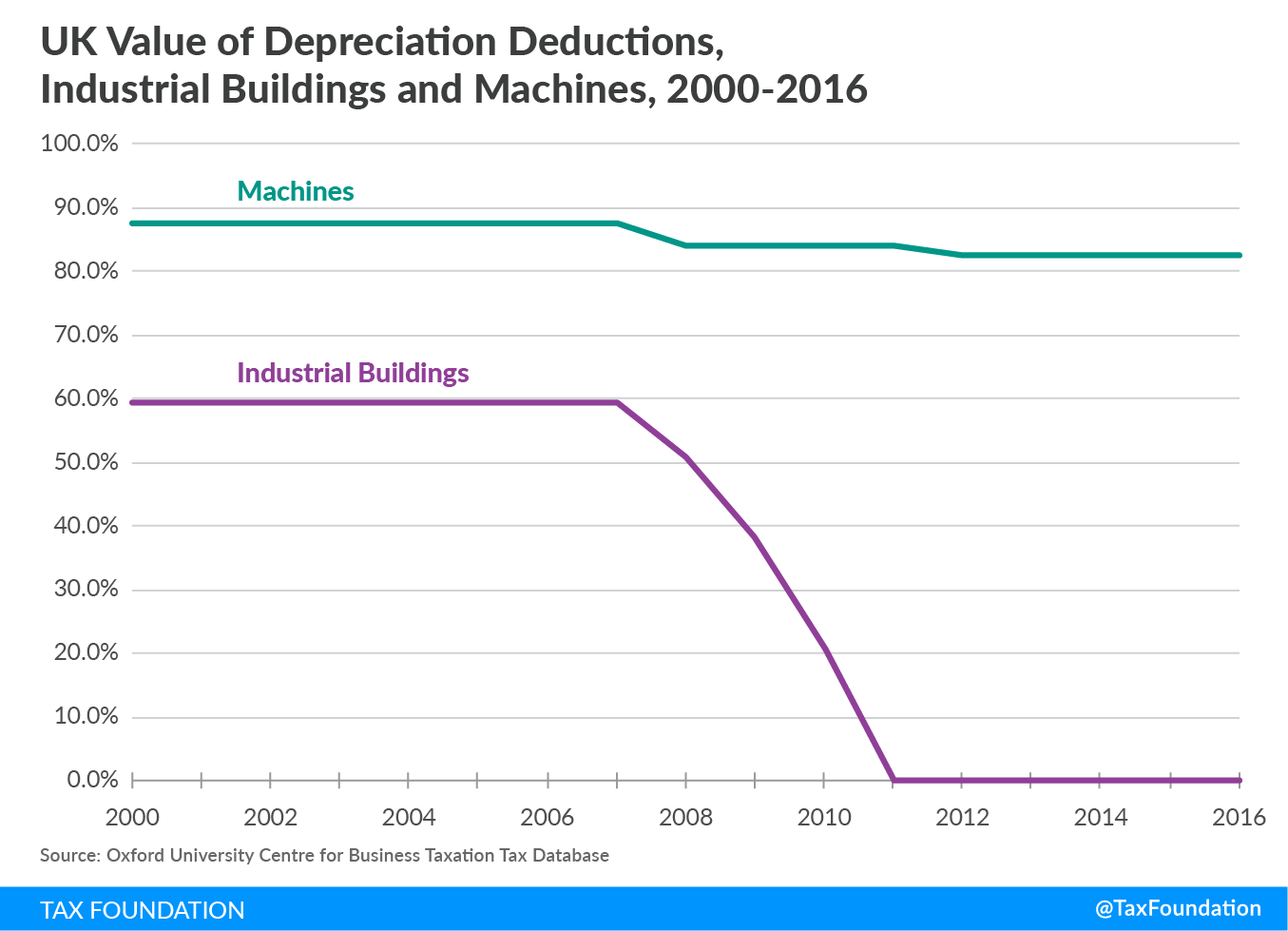

The most significant change the United Kingdom made to its corporate tax baseThe tax base is the total amount of income, property, assets, consumption, transactions, or other economic activity subject to taxation by a tax authority. A narrow tax base is non-neutral and inefficient. A broad tax base reduces tax administration costs and allows more revenue to be raised at lower rates. is its treatment of capital investments. Corporations that make capital investments are required to deduct the costs of these investments over a number of years according to a schedule. Asset lives vary by type of assets and countries vary in how quickly they allow companies to depreciate them. The longer capital assets are written off, the more corporations need to pay and the more the government collects in tax over the life of an investment. This is because deductions made over time lose value due to both inflation and the time value of money.

Between 2008 and 2013, the United Kingdom reduced the value of deductions for machines and industrial buildings. The present value deduction (the percent of the cost of an investment a company can deduct over its life) for machines fell from 87.5 percent to 84 percent from 2008 to 2012. Over the same period, industrial buildings fell from 59.2 percent to zero. This means that corporations cannot write off the cost of investing in buildings over time at all!

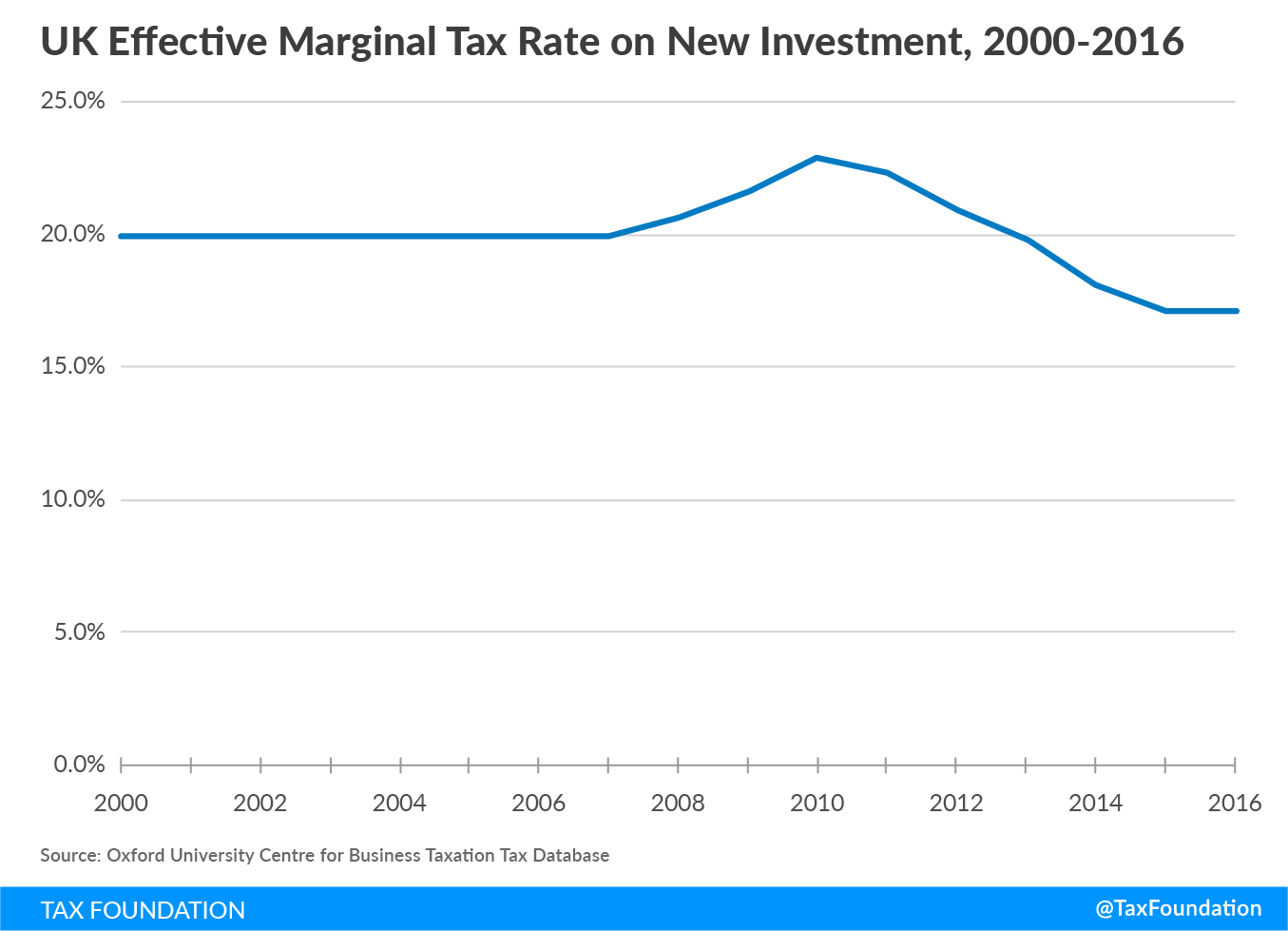

Not only did these legislative changes to the UK’s corporate tax base help offset the revenue impact of cutting its corporate tax rate, it also potentially offset the economic benefit as well. The length of time an asset needs to be written off impacts the taxes an investment faces on the margin. Longer asset lives increase the tax even as the statutory tax rate falls. According to Oxford University Centre for Business Taxation, the UK’s effective marginal tax rate (EMTR) on new investment actually climbed from around 20 percent in 2007 to 23 percent in 2010 even as the corporate rate declined by five percentage points. Overall, the EMTR only fell by three percentages points from 2007 and 2016, from 20 percent to 17 percent, while the statutory corporate tax fell by 10 percentage points.

It’s worth noting that many countries made the trade of longer asset lives for lower statutory rates. Capital allowances are less generous in developed countries than they were thirty years ago.

Tax reform should focus on reducing the corporate tax rate. A high statutory corporate tax rate encourages profit shifting and discourages investment. However, lawmakers should be realistic about the trade-offs that are required to get to a lower rate. The UK’s experience tells us two things:

- First, it is very unlikely that a corporate tax cut would be self-financing. The UK cut its rate significantly, which was beneficial and probably didn’t lose as much revenue as the official estimates implied. However, it is very likely the rate cut would have resulted in lost revenue if not for the base-broadening measures they passed concurrently. If anything, this shows that lawmakers in the United States should take seriously the need to offset reductions in the corporate tax even if they should expect some revenue reflow from greater economic growth and reduced profit shiftingProfit shifting is when multinational companies reduce their tax burden by moving the location of their profits from high-tax countries to low-tax jurisdictions and tax havens. .

- Second, how you broaden the tax base matters. The base broadeners the UK used to offset the corporate tax cut’s revenue loss also offset a lot of the potential economic benefit of having a lower statutory tax rate. This is the trade-off the former Chairman of Ways and Means, Dave Camp made in his 2014 tax reform proposal and is why both the Joint Committee on Taxation and the Tax Foundation found that the plan would have a small impact on the economy even though it cut the corporate rate by 10 percentage points. This contrasts with the House GOP Blueprint, which would bring the corporate rate down without significantly reducing corporate revenue or lengthening asset lives and discouraging domestic investment.

Read more about the United Kingdom’s corporate tax cut

Share this article