The Treasury Department recently touted strong business investment in the years following the pandemic-driven recessionA recession is a significant and sustained decline in the economy. Typically, a recession lasts longer than six months, but recovery from a recession can take a few years. and pointed to the Biden administration’s industrial policies in the InflationInflation is when the general price of goods and services increases across the economy, reducing the purchasing power of a currency and the value of certain assets. The same paycheck covers less goods, services, and bills. It is sometimes referred to as a “hidden tax,” as it leaves taxpayers less well-off due to higher costs and “bracket creep,” while increasing the government’s spending power. Reduction Act (IRA) and CHIPS Act as key drivers.

The Treasury Department is right to highlight the importance of capital investment. Investment drives long-run growth and prosperity. It makes workers more productive, raising both overall economic productivity and worker wages. And generally, private investment carries a higher rate of return than public investment, making the private sector a key driver of growth.

But Treasury’s conclusions regarding the relevant policy drivers have some problems. The baseline used to measure overall investment growth is suspect, the underlying increase in industry-specific investment might not translate to overall productivity growth, and the analysis ignores broader, pro-investment policies at play.

Treasury’s Choice of Baseline Is Suspect

The Treasury analysis compares actual business investment with projections from the Blue Chip Economic Indicators monthly survey of economic forecasters for major firms and institutions. Treasury selected the October 2022 survey for its baseline, which estimated investment would grow at a 0.5 percent annualized rate in 2023. In actuality, investment grew at a much higher 4.3 percent rate in 2023. The selection of the October 2022 survey as a baseline for investment is arbitrary and potentially misleading. October 2022 was the bleakest month of the survey’s economic forecasts, as inflation then was showing little sign of abating. Contrastingly, the Blue Chip Economic Indicator surveys in early 2022 predicted investment growth of more than 4 percent in 2023, in line with the actual results.

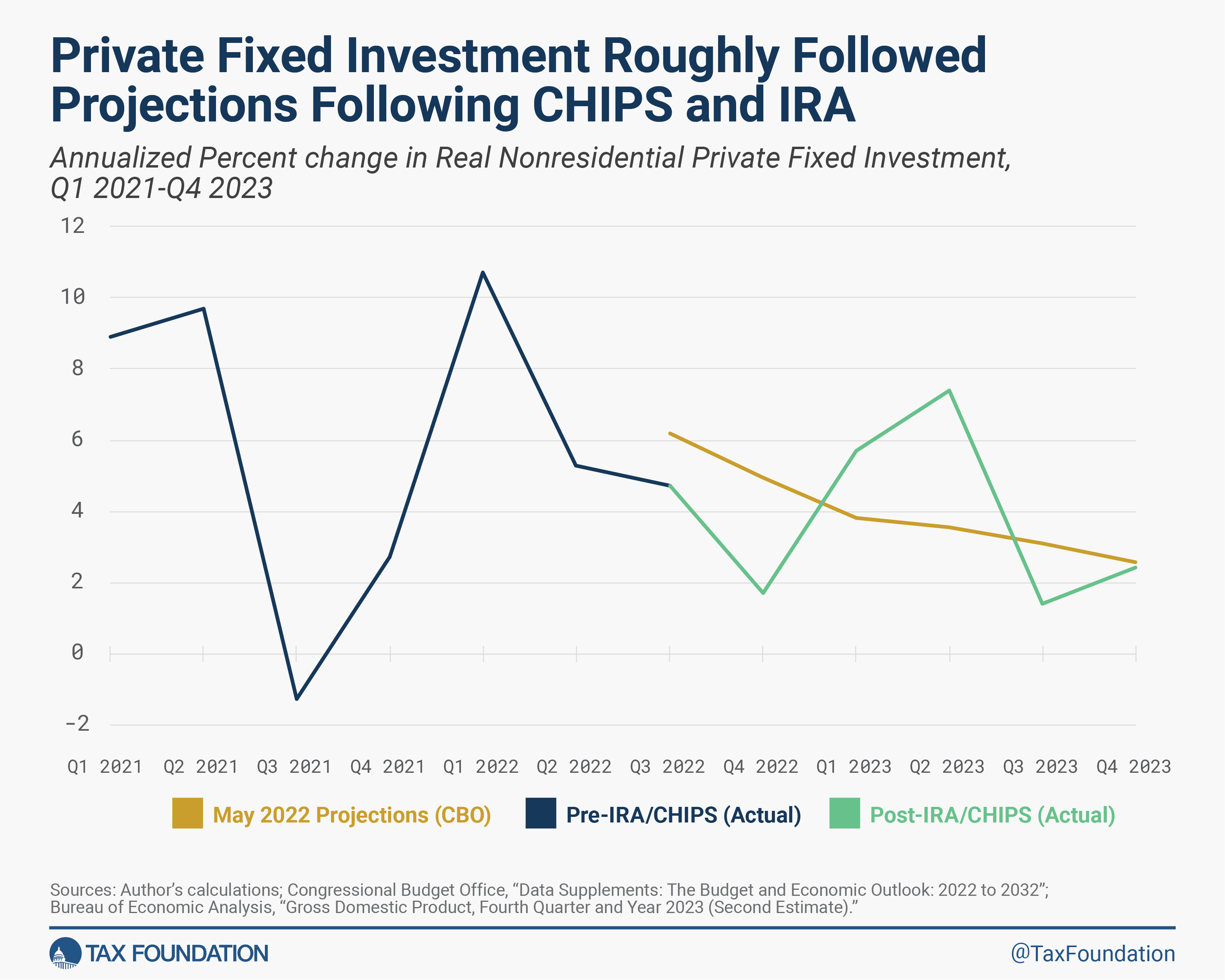

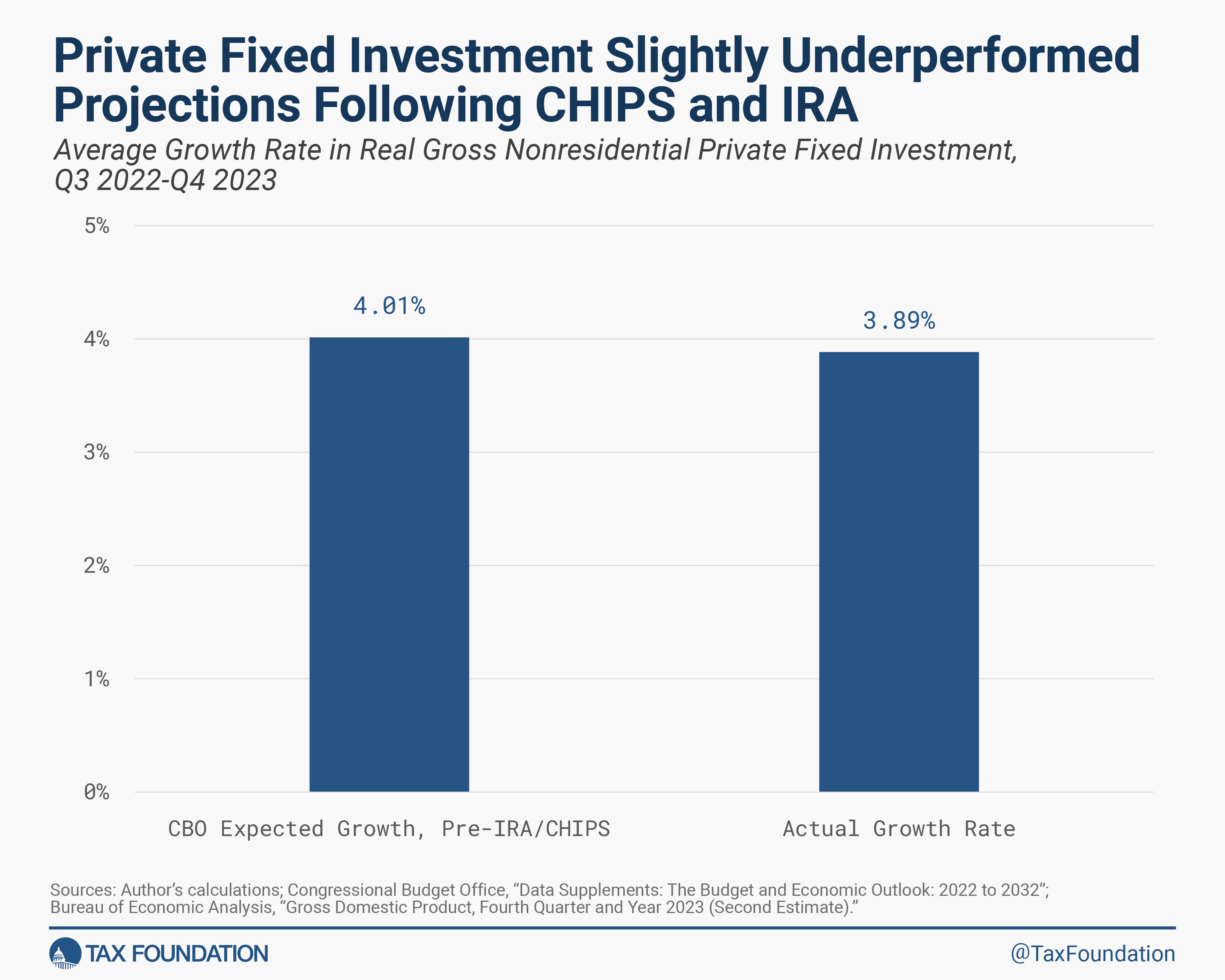

For an alternate baseline comparison, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) publishes detailed economic outlook projections twice a year, and the May 2022 version projected average annualized investment growth of 4.0 percent from Q3 2022 to Q4 2023. Over the same period, investment actually grew by 3.9 percent—ever so slightly below the most recent pre-IRA/CHIPS CBO economic outlook.

This CBO-based counterfactual is not ironclad proof the CHIPS Act and the Inflation Reduction Act did not increase nonresidential fixed investment—plenty of other factors in 2022 and 2023 put downward and upward pressure on investment, most notably interest rate hikes and rising energy prices. However, it is a more reasonable counterfactual baseline than projections from October 2022, a few months after enactment of the major bills that also happens to feature the lowest investment projection of the year.

Industry-Specific Investment Might Not Equal Overall Productivity Growth

While investment has grown, that growth has been heavily concentrated in a few industries. When looking at Bureau of Economic Analysis data on real nonresidential fixed investment between Q3 2022 and Q4 2023, manufacturing structures investment is responsible for roughly 40 percent of the growth. When looking at the change in all private fixed investment, manufacturing structures investment is responsible for an even larger share of the growth over the same period, due to a slowdown in residential housing construction. And as the Treasury Department highlights, the increase in manufacturing construction investment is heavily concentrated in computer, electrical, and electronic manufacturing. This fact raises two major concerns.

For one, some of the investment surge in electronics manufacturing predates the CHIPS Act and the Inflation Reduction Act. Supply chain disruptions driven by both the pandemic and the post-pandemic surge in demand led many companies to diversify their supply chains and reinvest in the United States. Investment in computer, electronic, and electrical manufacturing structures rose from $11.6 billion in the 12 months preceding August 2021 to $43.5 billion in the 12 months preceding August 2022 (although after adjusting for the rising cost of materials over the same timeframe, the increase is less extreme). The Cato Institute recently cataloged how a large share of major investment projects were announced before the CHIPS Act and the Inflation Reduction Act.

The other concern is that high spending may not translate to real production. In the case of the Census’s Value of Construction Put in Place data set, the value includes both hard costs, like raw materials and construction labor, and soft costs, like overhead and office expenses, related to the project. For one, hard costs have grown much faster than general inflation, which the Treasury Department acknowledges. The soft costs, meanwhile, could mean the “investment” numbers are reflective of high compliance challenges and navigating red tape rather than work being done. While we expect some substantial construction time for major projects like semiconductor fabs to get built, if the many anecdotes regarding delays, shortages, and extensive regulatory compliance work are reflective of the broader trends, it may mean a serious disconnect.

Furthermore, even if construction is completed, the investment could ultimately prove unproductive. Both CHIPS and the IRA aim to shift investment by subsidizing specific industries, making projects that would have a negative expected return without a subsidy suddenly viable. However, those projects may have been economically unviable for a reason. Regulatory hurdles and a shortage of specialized workers (among other factors) may mean little in terms of output generated from subsidized semiconductor fabs or new clean energy projects.

Now, both pieces of legislation may have justifications that are not related to greater overall productivity gains. CHIPS is about competition with China and supply chain diversification and the Inflation Reduction Act is about climate change (though competition with China is also part of the puzzle). But the jury is still out on whether CHIPS and the Inflation Reduction Act will successfully meet those objectives, too—and that will not be clear for some time.

Broad Investment Incentives Are Needed

CHIPS and the IRA could perhaps be justified on idiosyncratic national security or climate grounds. But they are not substitutes for broad economic policymaking. The vast majority of manufacturing industries, not to mention industries outside of the manufacturing sector, do not benefit from the new policies. The American economy is broad and multifaceted, and targeting one or a couple of industries with support is not a recipe for shared economic growth. Increasing investment incentives across the board is.

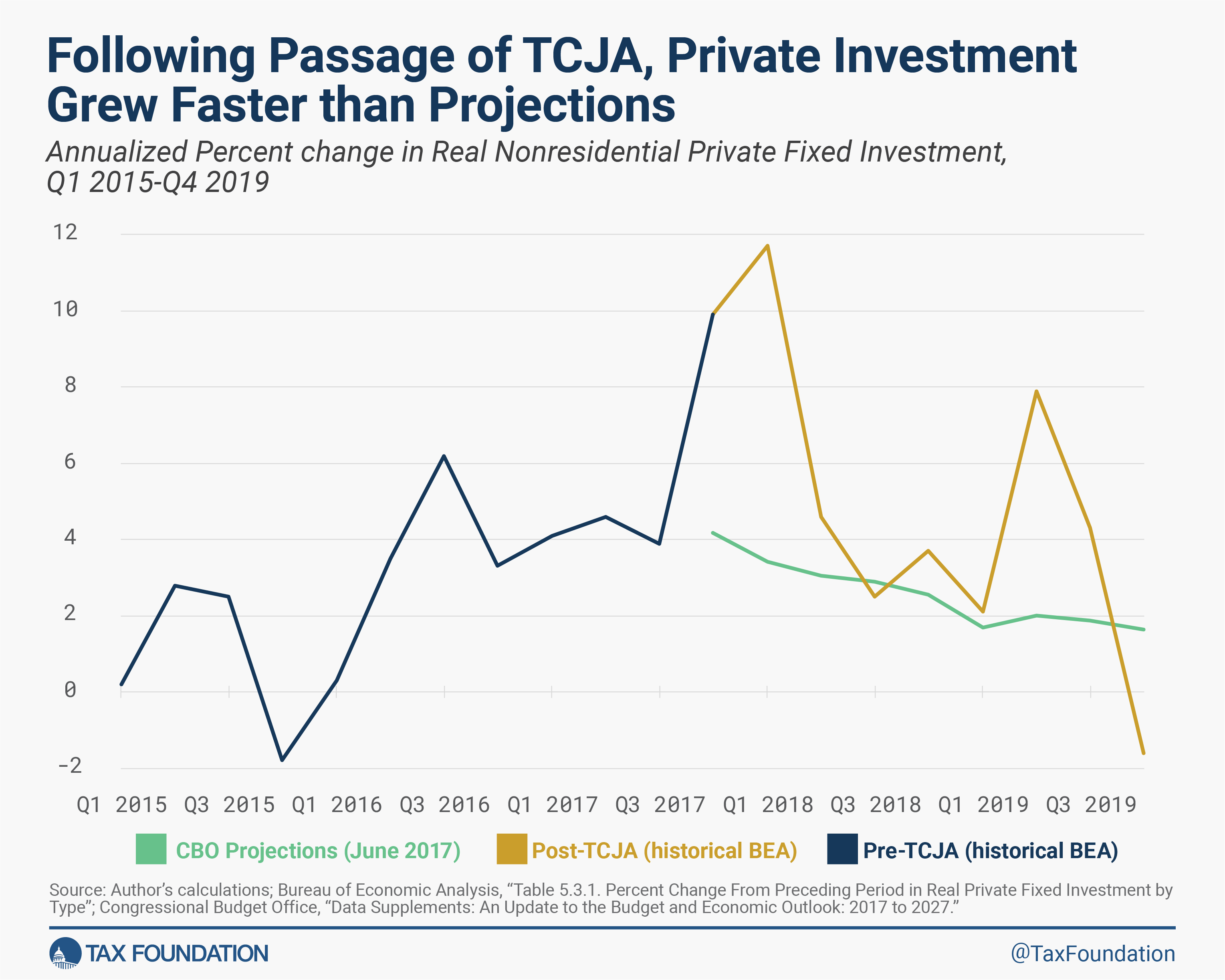

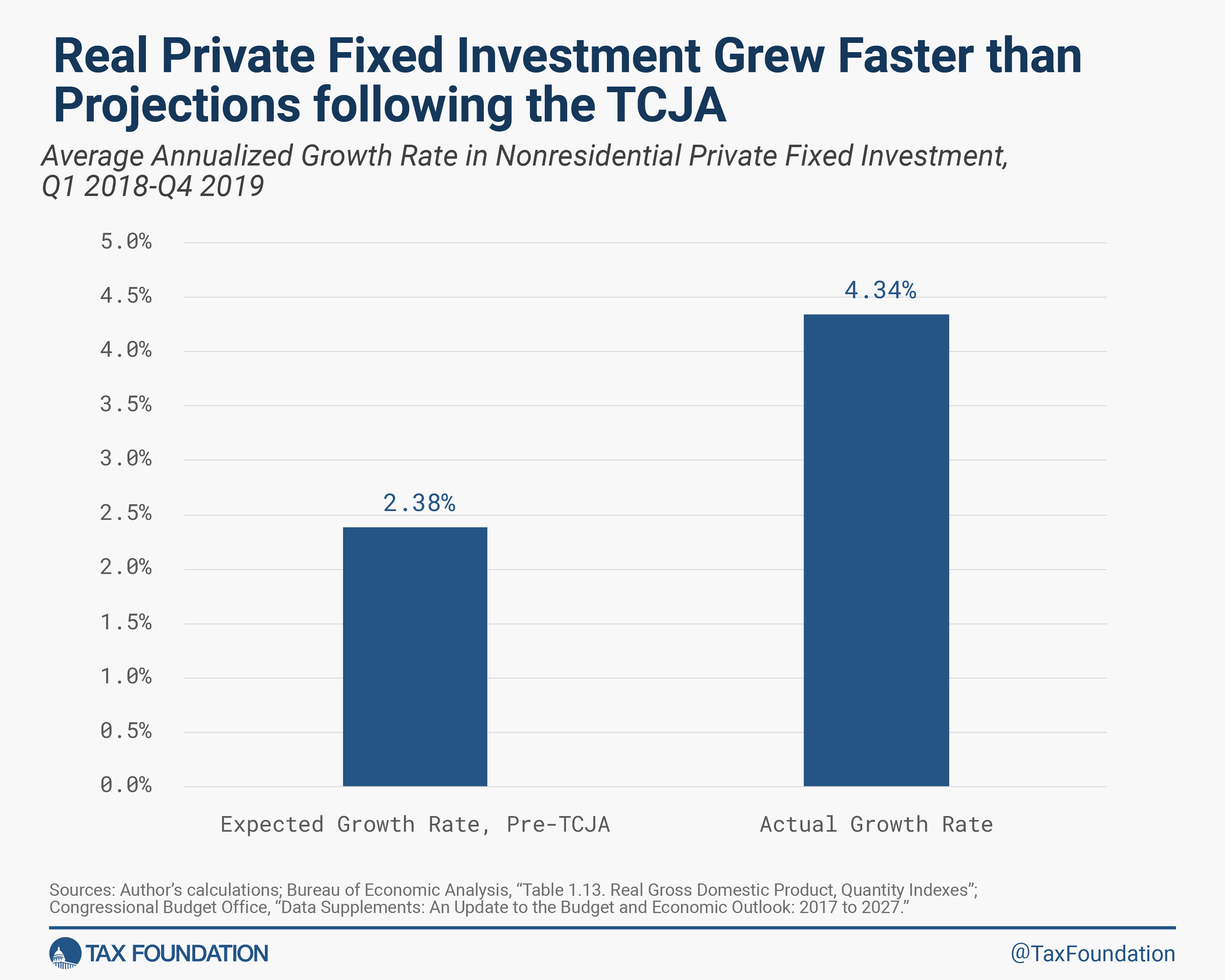

The post-TCJA economy illustrates this well. Instead of dramatically changing the returns to capital for one industry, the TCJA increased investment incentives across the board, predominantly due to the lower corporate taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. rate and 100 percent bonus depreciationBonus depreciation allows firms to deduct a larger portion of certain “short-lived” investments in new or improved technology, equipment, or buildings in the first year. Allowing businesses to write off more investments partially alleviates a bias in the tax code and incentivizes companies to invest more, which, in the long run, raises worker productivity, boosts wages, and creates more jobs. for short-lived assets. Investment well outpaced pre-law projections in the eight quarters following the law. And recent academic work has confirmed the role these broad tax changes played in driving new investment growth.

Furthermore, the economy was still benefitting from the TCJA’s broadly improved tax environment coming out of the pandemic. During the recovery from the Great Recession, the corporate tax rate was 35 percent. During the post-COVID recovery, the corporate tax rate was 21 percent. Businesses could fully deduct the cost of equipment purchases for the entirety of 2021 and 2022, with access to 80 percent bonus depreciationDepreciation is a measurement of the “useful life” of a business asset, such as machinery or a factory, to determine the multiyear period over which the cost of that asset can be deducted from taxable income. Instead of allowing businesses to deduct the cost of investments immediately (i.e., full expensing), depreciation requires deductions to be taken over time, reducing their value and discouraging investment. in 2023, while during most of the Great Recession recovery, companies only had access to 50 percent bonus depreciation (except between September 2010 and the end of 2011).

The US economy is strong. But many proposals, such as raising the corporate tax rate to 28 percent, would reverse some of the gains we have made in recent years. Even with the status quo, we’re left with a tax code that can thwart investment in general while providing offsetting subsidies for favored, or connected, industries.

Share this article