While there is still plenty of work to be done to get unemployed Americans back to work, the U.S. economy as a whole is now recovering strongly from the pandemic-induced economic downturn, outperforming forecasts from earlier in the year and outperforming most other developed countries. The Atlanta Federal Reserve’s “nowcast” indicates that the U.S. economy grew at an annual rate of 35.2 percent in the third quarter—an estimate that has increased considerably in recent months as economic indicators come in better than expected.

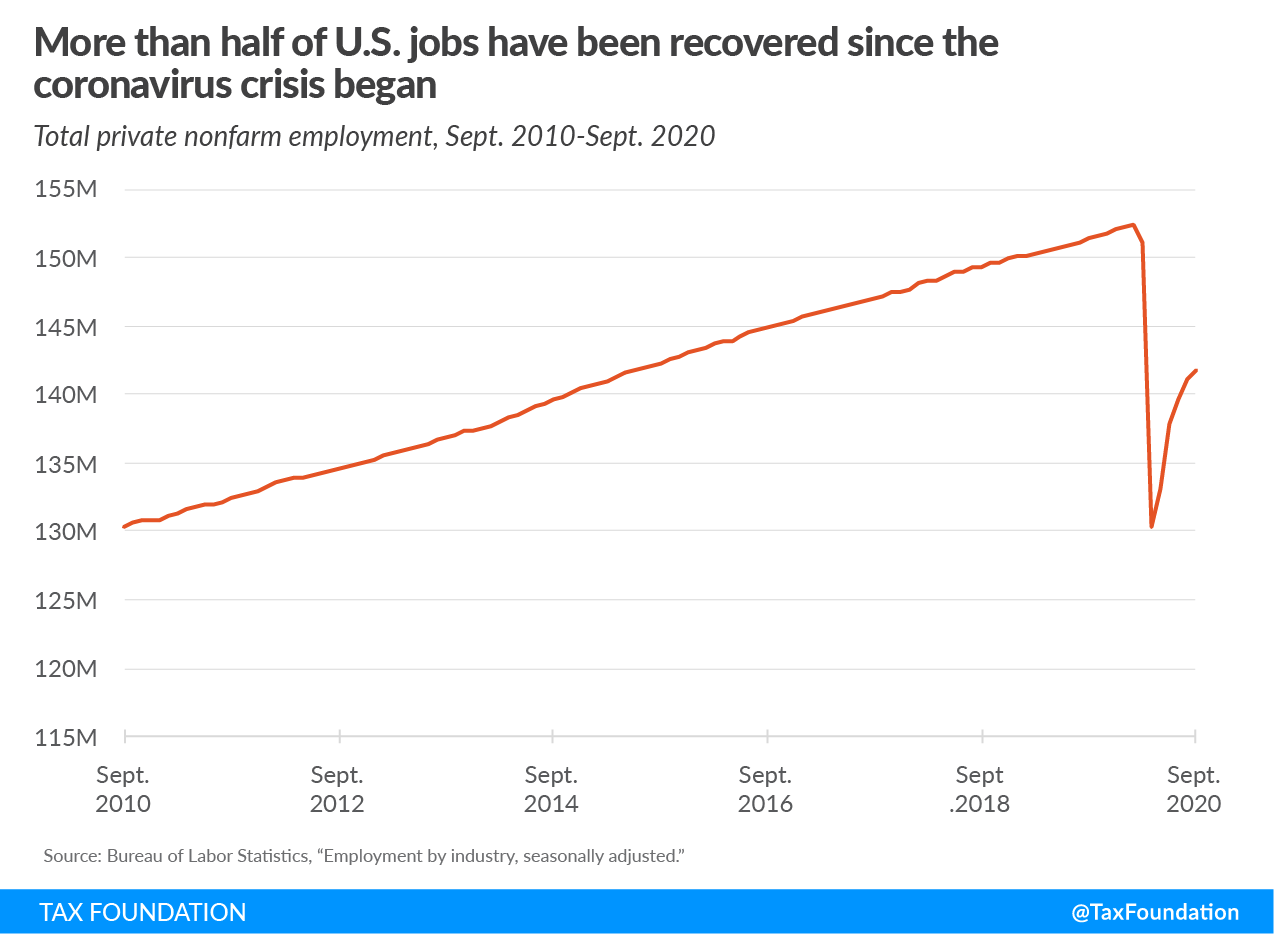

More than half of the 22 million jobs lost in March and April have been regained (see Figure 1), though gains have not been proportional. Most forecasters continue to anticipate a decline in GDP for the year as a whole due to the severe contraction in the first half, but those estimates have improved considerably as well. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) projects that the U.S. economy will shrink 3.8 percent in 2020—about half the decline the OECD forecast in June and a smaller contraction than the OECD currently projects for most developed countries.

This bounceback of the U.S. economy can be attributed to multiple factors, including accommodative policy by the Federal Reserve and fiscal measures enacted during the crisis, which helped bolster liquidity and consumption. At the same time, some sectors have experienced a boom thanks to changing conditions that have allowed certain companies to prosper despite the pandemic and recessionA recession is a significant and sustained decline in the economy. Typically, a recession lasts longer than six months, but recovery from a recession can take a few years. .

One underappreciated factor may be the TaxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), which instituted a number of pro-growth measures including a reduction in the corporate tax rate from 35 percent to 21 percent beginning in 2018, substantially reducing the tax burden on business investment and boosting after-tax earnings.

At the time of its passage, we forecast that the TCJA would boost GDP growth by nearly a half percentage point in 2020, largely due to a multiyear process of building up the capital stock in response to a lower marginal tax rate on capital, leading to a more productive and more highly paid workforce. This marginal effect still works even now that investment plans for many businesses have radically changed in light of the pandemic (e.g., retailers needed to suddenly build out the capability to sell remotely and deliver), and the TCJA made more of those new investment plans viable.

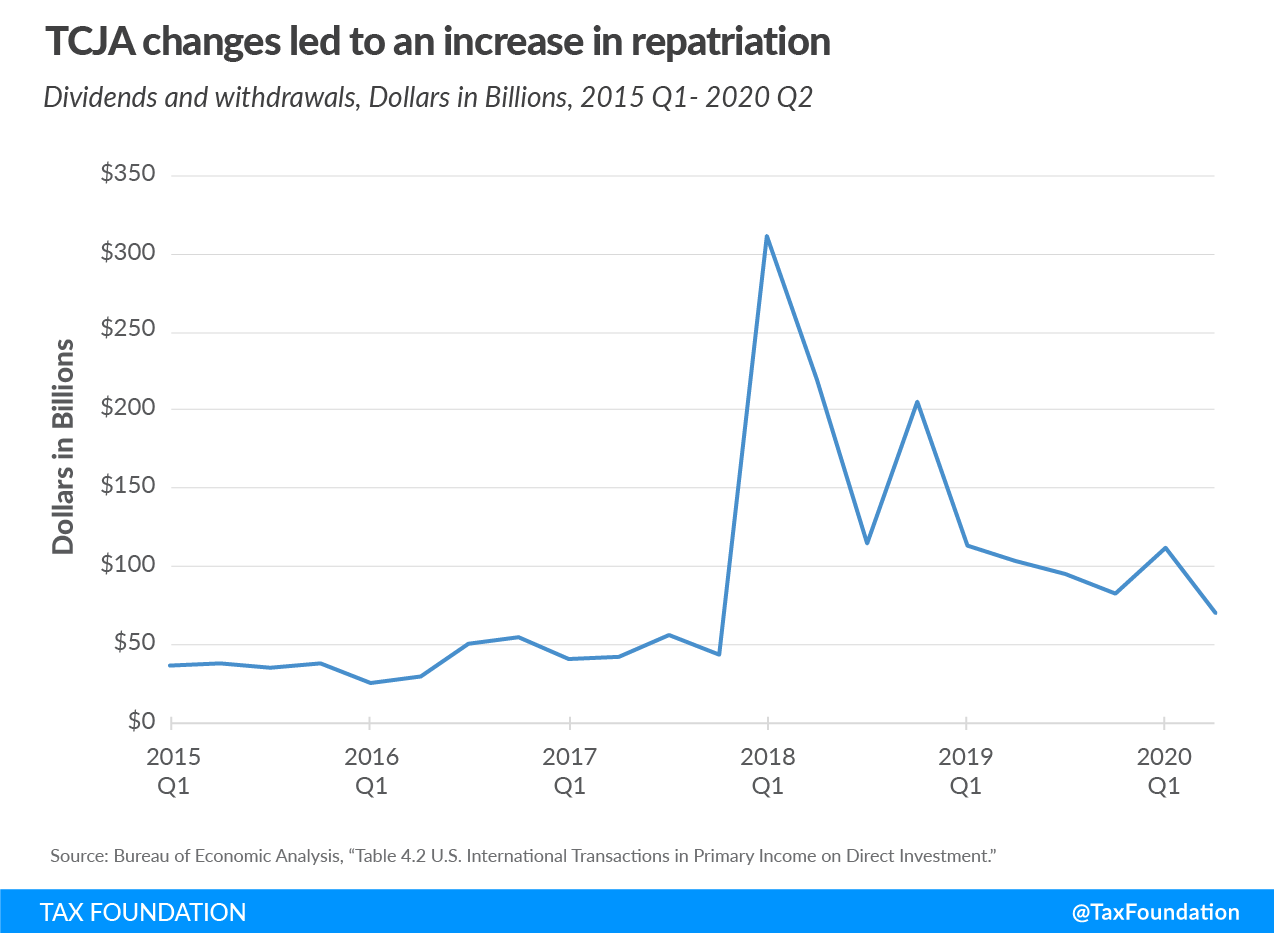

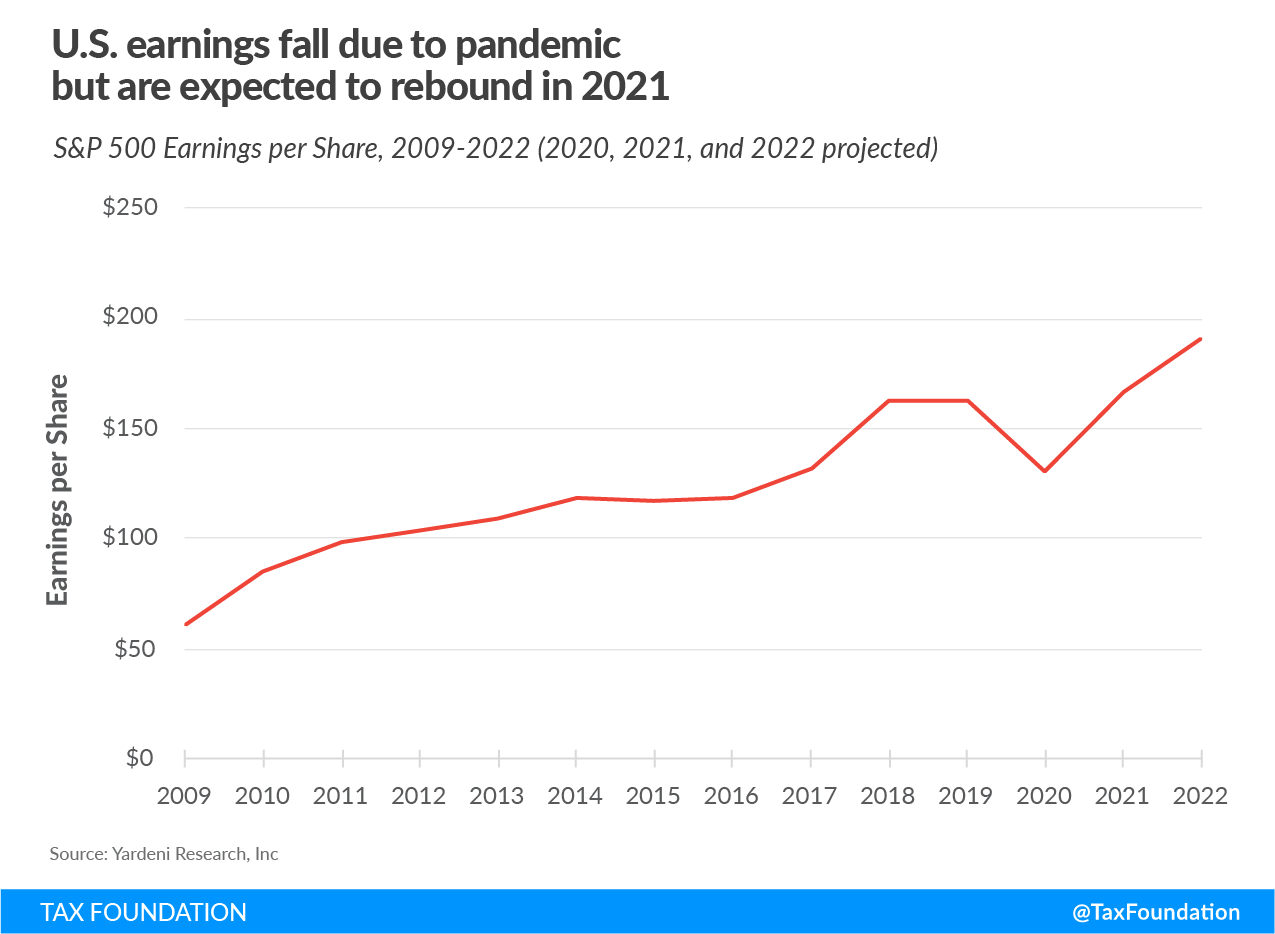

Perhaps as important to the economic recovery this year has been the TCJA’s boost to corporate after-tax earnings and liquidity leading up to the pandemic. This was largely due to the lower corporate tax rate and changes to the international tax system that reduced the incentive to keep earnings abroad, leading to a sharp increase in repatriation, the process by which companies bring overseas earnings back to the United States (see Figure 2). The earnings of S&P 500 companies rose 22.7 percent in 2018, the first full year the TCJA went into effect, and essentially remained at that level in 2019 (see Figure 3). Earnings are expected to fall 20 percent this year in the wake of the pandemic before rebounding 27 percent next year to about the same level of 2019.

While increased repatriationRepatriation is the process by which multinational companies bring overseas earnings back to the home country. Prior to the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), the US tax code created major disincentives for US companies to repatriate their earnings. Changes from the TCJA eliminate these disincentives. and higher earnings from existing investments are not the drivers of future growth, they do help firms bridge revenue gaps through the crisis from a liquidity standpoint. The same is true of households, which also have relatively strong balance sheets when compared to the Great Recession of 2007 to 2009, largely due to the fiscal measures the government enacted at the start of the current crisis.

The rebound in earnings and the broader economy is good news in that it appears to be staving off the anticipated “wave of bankruptcies” related to the pandemic and its aftermath. While there have been a number of high-profile corporate bankruptcies this year, particularly in the hard-hit oil and gas and retail sectors, most of those occurred before the economy started to recover in the third quarter. Bankruptcies tend to be a lagging indicator, and the relief provided by Congress that lasted through the summer likely suppressed the number of bankruptcies we would have otherwise seen over the spring and summer.

The ongoing recovery is beating expectations, but the economy is not out of the woods. The latest bankruptcy filings through September indicate an uptick for small businesses, and many expect an increase given the lapse in federal aid. The latest unemployment numbers indicate many households are still struggling and the number of people in poverty is on the rise.

All of this suggests that further fiscal relief should be targeted accordingly and policies such as increasing marginal tax rates on capital or labor should be avoided as they may undercut a nascent economic recovery.

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

Subscribe