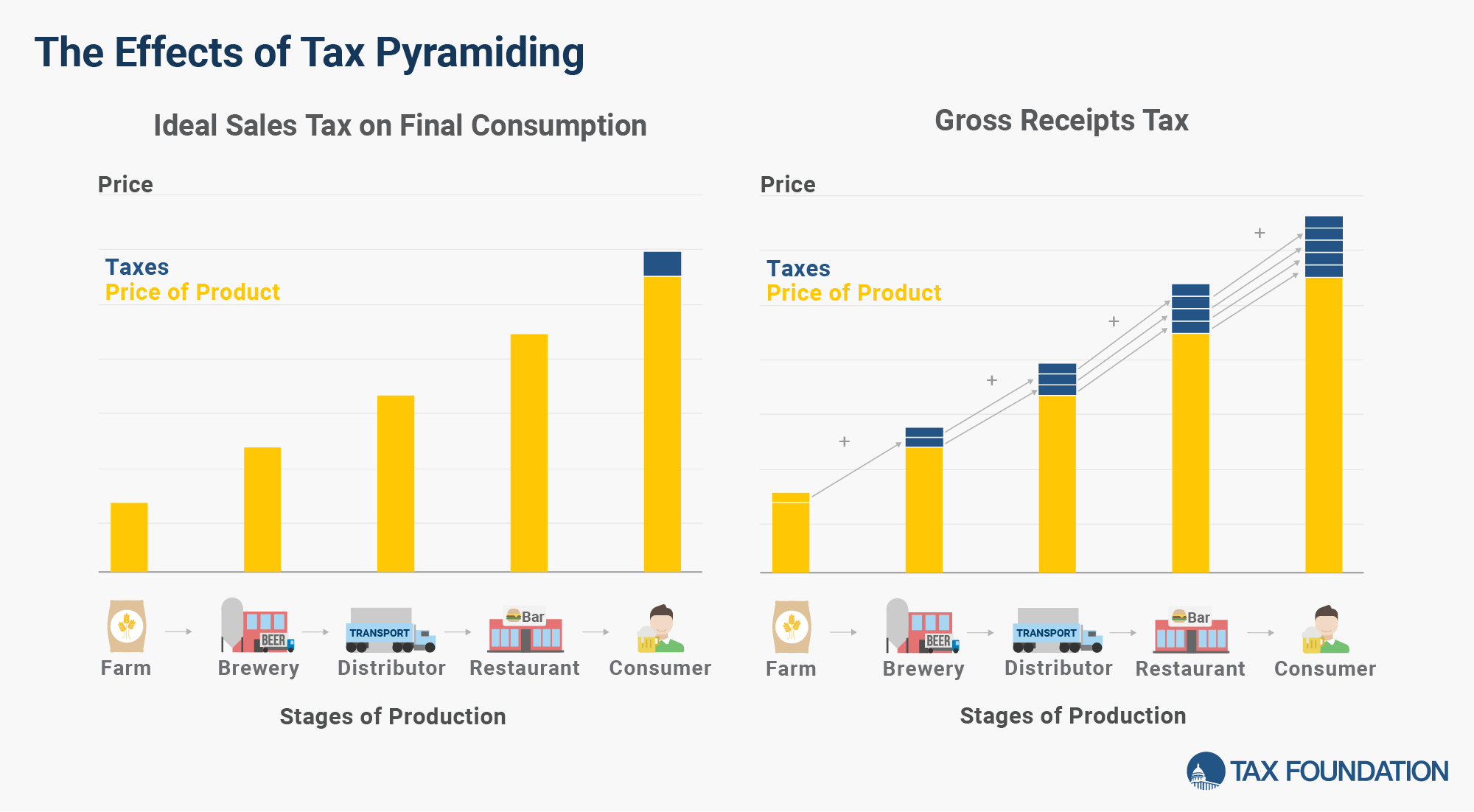

Tax pyramiding occurs when the same final good or service is taxed multiple times along the production process. This yields vastly different effective tax rates depending on the length of the supply chain and disproportionately harms low-margin firms. Gross receipts taxes are a prime example of tax pyramiding in action.

What Is the Impact of Tax Pyramiding?

Tax pyramiding causes a number of inefficient economic outcomes. It increases effective tax rates in a nontransparent way, as the tax rate is applied to the same economic value multiple times, imputing a greater cost of tax at each stage of production. Under a gross receipts tax, also known as a turnover tax, businesses at each stage of production will only see a relatively low statutory rate of taxation because previous taxes have already been factored into the cost of the product or service at each stage of production. Neither businesses nor consumers will be able to transparently see that the price of a product or service is higher than it would otherwise be had there not been multiple layers of tax at earlier production stages. The amount of the tax that is passed along to the purchaser is determined by how sensitive the purchaser is to the increase in price; sellers will be more inclined to raise prices on buyers who are less likely to reduce their purchases by switching to alternatives that are less affected by the tax.

Under a gross receipts tax, the degree of tax pyramiding in an industry will depend on how many production stages occur before a good or service is consumed. A gross receipts tax incentivizes firms to vertically integrate production processes in order to avoid multiple levels of taxation.

What Is an Example of Tax Pyramiding?

Consider the process required to produce a dresser in a jurisdiction which imposes a gross receipts tax. When a logger sells wood to a lumberyard, the gross receipts tax would be applied to the receipt collected by the logger. The logger may raise the price of the product to accommodate the tax, which shifts the cost of the tax onto the lumberyard. When the lumberyard processes the wood into lumber and sells it to a furniture manufacturer, the price paid would include the already-taxed value provided by the logger and would add the next layer of tax on the new transaction. A tax would be applied again when a furniture store buys the dresser from the manufacturer, and once more when a consumer purchases the dresser from the furniture store. Thus, the production of a dresser would generate multiple levels of taxable transactions that impose a greater effective tax rate on the final consumer than what is apparent in the statutory tax rate.

Contrast the tax pyramiding process with a well-designed sales tax. In the case of a dresser, the business-to-business transactions needed to produce the dresser would not be taxed. The tax would only be applied once, when the final retail consumer purchases the dresser, and thus no tax pyramiding occurs.

Stay updated on the latest educational resources.

Level-up your tax knowledge with free educational resources—primers, glossary terms, videos, and more—delivered monthly.

Subscribe