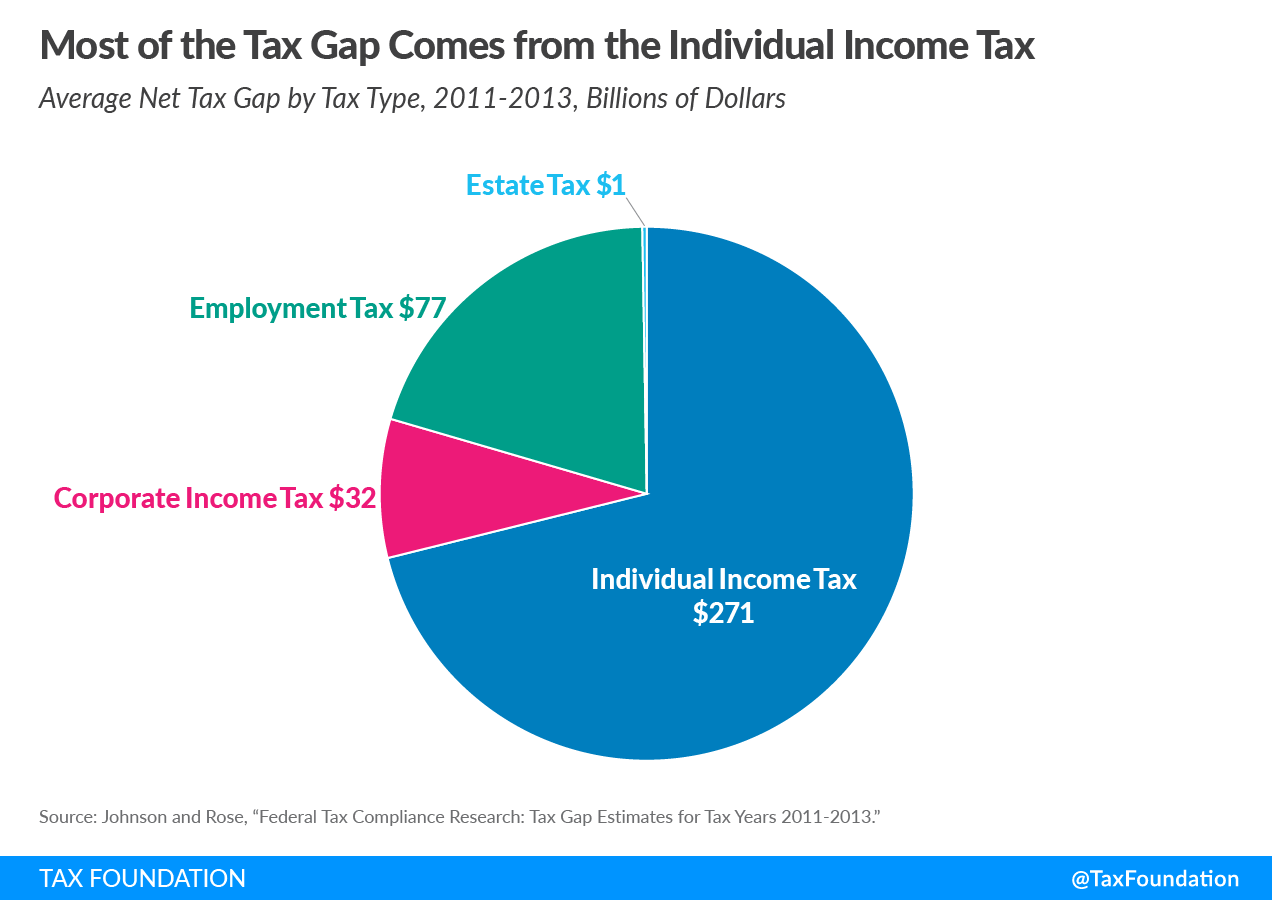

The tax gap is the difference between taxes legally owed and taxes collected. The gross tax gap in the U.S. accounts for at least $441 billion in lost revenue each year, according to the latest estimate by the IRS (2011 to 2013), suggesting a voluntary taxpayer compliance rate of 83.6 percent. The net tax gap is calculated by subtracting late tax collections from the gross tax gap: from 2011 to 2013, the average net gap was around $381 billion.

What Drives the Gap?

The majority of the tax gap comes from the individual income tax: of the $381 billion average net gap, about $271 billion could be attributed to the personal income tax. Within the personal income tax, the gap is heavily concentrated in taxes owed on income not subject to withholding or reporting requirements.

There are a few driving factors behind the tax gap. Tax complexity may be one factor because taxpayers must navigate tax rules and forms to properly report income and calculate the taxes they owe and often make errors. Americans spend over 8.1 billion hours on tax compliance. There is evidence that complexity drives a large part of the tax gap for self-employed workers and independent contractors, as these taxpayers may not know how to properly report and remit income and self-employment tax. High compliance burdens could also end up reducing “tax morale,” roughly defined as the willingness of taxpayers to voluntarily comply fully.

Reducing the Tax Gap

Some tax gap will always exist. However, reducing the gap would improve trust in the tax system, as taxpayers would know that others are following the same set of rules, and generate revenue without raising tax rates or broadening the tax base. On the other hand, certain efforts to reduce tax nonpayment with more aggressive IRS action and regulation could end up imposing major compliance costs for taxpayers.

Policymakers should consider both the tax gap and compliance costs for taxpayers. Some policies could help reduce both. For example, a simpler, more economically sound tax code would be both easier for taxpayers to comply with and for the IRS to administer. On the more technical side, improvements to the IRS’s information technology could help them better allocate existing enforcement resources to returns more likely to be underpaid. Alternatively, while broadly increasing audit rates could raise revenue, it could also lead to many audits for taxpayers that did pay their proper liability.

Stay updated on the latest educational resources.

Level-up your tax knowledge with free educational resources—primers, glossary terms, videos, and more—delivered monthly.

Subscribe