Key Findings:

- TaxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. triggers, a series of tax reductions or tax policy changes implemented over time subject to meeting pre-established revenue (or similar) targets, are an increasingly popular mechanism for phasing in tax reform measures subject to revenue availability.

- Well-designed triggers limit the volatility and unpredictability associated with any change to revenue codes, and can be a valuable tool for states seeking to balance the economic impetus for tax reform with a governmental need for revenue predictability. Some triggers are designed to target a certain degree of revenue growth, while others operate within a framework of overall reductions or seek to maintain revenue neutrality.

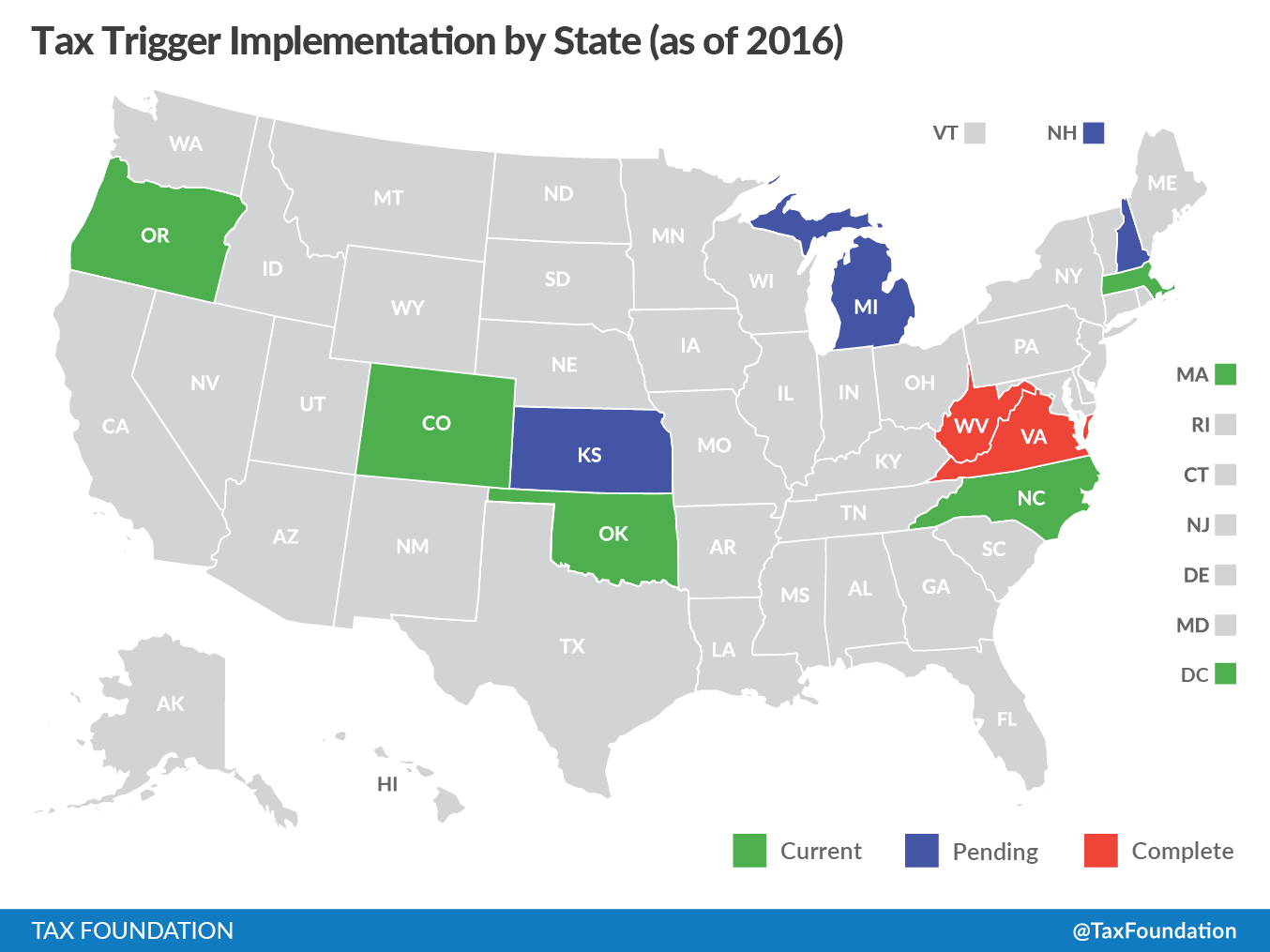

- Eleven states and the District of Columbia have turned to tax triggers to implement contingent tax rate reductions or other reforms in recent years, but the designs of these triggers have varied widely.

- Baselines, benchmarks, exclusions, and implementation mechanisms all require careful consideration in tax trigger design. Well-designed triggers specify baseline revenue levels and establish meaningful benchmarks which mitigate the influence of year-over-year revenue volatility.

Introduction

When North Carolina legislators committed to comprehensive tax reform in 2013, they broadened tax baseThe tax base is the total amount of income, property, assets, consumption, transactions, or other economic activity subject to taxation by a tax authority. A narrow tax base is non-neutral and inefficient. A broad tax base reduces tax administration costs and allows more revenue to be raised at lower rates. s and eliminated exemptions to fund rate reductions—but then turned to “tax triggers” to implement a schedule of further rate cuts, as revenue permitted, in subsequent years. In the District of Columbia, council members decided to link the scope of planned tax reform to revenue availability as the reform process unfolded. Seeking a lower individual income taxAn individual income tax (or personal income tax) is levied on the wages, salaries, investments, or other forms of income an individual or household earns. The U.S. imposes a progressive income tax where rates increase with income. The Federal Income Tax was established in 1913 with the ratification of the 16th Amendment. Though barely 100 years old, individual income taxes are the largest source of tax revenue in the U.S. rate, Massachusetts policymakers opted for a gradual phase-in of rate cuts, proceeding only when revenue growth was more than sufficient to absorb the rate change. And in West Virginia, a desire to prepare for future economic downturns was joined with efforts to make the state’s tax system more competitive through legislation providing corporate income taxA corporate income tax (CIT) is levied by federal and state governments on business profits. Many companies are not subject to the CIT because they are taxed as pass-through businesses, with income reportable under the individual income tax. rate reductions contingent on the size of the state’s rainy day fund.

In each of these cases, and many others, states turned to triggers as a way to implement or phase in tax rate reductions or other tax reform measures as revenues permitted. Tax triggers are a new take on an old concept: contingent enactment of a legislative provision. States have long relied upon bills with contingent enactment clauses, providing that certain features of new legislation shall only be operative if certain conditions are met. Tax triggers build on this model, making tax reform measures contingent on state revenues meeting or exceeding established targets.

Tax triggers can help ensure revenue stability and limit the uncertainty associated with changes to the tax code while providing an efficient way for states to dedicate some portion of revenue growth to tax relief.[1] States are increasingly turning to tax triggers as a component of tax reform measures. As tax trigger designs proliferate, the opportunity arises to examine the different parameters and mechanisms states have employed, and to develop best practices for future tax triggers.

Well-designed triggers ensure that benchmarks reflect meaningful revenue growth, rather than capturing a rebound from a year of weak revenues or the effects of inflationInflation is when the general price of goods and services increases across the economy, reducing the purchasing power of a currency and the value of certain assets. The same paycheck covers less goods, services, and bills. It is sometimes referred to as a “hidden tax,” as it leaves taxpayers less well-off due to higher costs and “bracket creep,” while increasing the government’s spending power. . They also avoid undue time constraints which can derail, rather than delay, the implementation of a program of contingent reforms. When properly constructed, tax triggers serve as a valuable mechanism for implementing responsible tax reform.

This paper reviews the design of existing state tax triggers and suggests a framework for analysis, distilling the many structural variations into four broad categories: benchmarks, baselines, exclusions, and mechanisms. It then offers some preliminary observations on optimizing tax trigger design to achieve intended legislative purposes.

Tax Triggers in the States

In recent years, eleven states and the District of Columbia have turned to tax triggers to implement contingent tax rate reductions and other reforms, or to issue taxpayer refunds. Tax cut phase-ins through trigger mechanisms are currently underway in five states and the District of Columbia, while triggers have been adopted for future years in another four states. Two states have fully implemented the contingent tax changes anticipated under their triggers.

Benchmarks vary greatly across states. Some states rely on year-to-year revenue changes, while others establish baselines. Some devote surplus revenues to tax relief, while others set revenue growth limitations. Several use projected revenue, while others rely upon prior-year collection figures. A few tie triggers to specific years, while others leave them open-ended. Some account for inflation, while others employ triggers pegged to nominal values.

The mechanisms states employ to implement tax reforms once triggered are nearly as varied as the benchmarks they establish. Many states institute a schedule of specified reductions: for instance, reducing the corporate income tax rate from 6.0 to 5.5 percent once a certain revenue threshold is reached. Others promulgate rate reductions by formula, calculating the size of the tax cut based on the amount of revenue subject to the trigger. States which offer one-year refunds in lieu of long-term reform may utilize credits to return surplus revenues to taxpayers.

The taxpayer refund provisions embodied in Colorado’s Taxpayer Bill of Rights and Oregon’s “kicker” are not true triggers in the sense that they do not implement any permanent change in state tax codes. They do, however, provide contingent single-year tax relief, in the form of tax creditA tax credit is a provision that reduces a taxpayer’s final tax bill, dollar-for-dollar. A tax credit differs from deductions and exemptions, which reduce taxable income, rather than the taxpayer’s tax bill directly. s and temporary tax reductions, predicated on state revenues exceeding certain thresholds. As such, they are considered here by way of comparison with more traditional tax triggers.

As Table 1 shows, seven states and the District of Columbia have adopted triggers with statutory schedules, while four states’ triggers are driven by formula. In two of the formula states, tax triggers initiate a one-year tax refundA tax refund is a reimbursement to taxpayers who have overpaid their taxes, often due to having employers withhold too much from paychecks. The U.S. Treasury estimates that nearly three-fourths of taxpayers are over-withheld, resulting in a tax refund for millions. Overpaying taxes can be viewed as an interest-free loan to the government. On the other hand, approximately one-fifth of taxpayers underwithhold; this can occur if a person works multiple jobs and does not appropriately adjust their W-4 to account for additional income, or if spousal income is not appropriately accounted for on W-4s. rather than implementing a permanently lower rate.

|

State |

Tax |

Benchmarks |

Method |

Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

CO |

PIT |

Revenue exceeds inflation + pop. growth + excess revenue cap |

Refund |

Current |

|

DC |

PIT |

Mid-year revenue estimate exceeds initial revenue estimate |

Schedule |

Current |

|

CIT |

Mid-year revenue estimate exceeds initial revenue estimate |

Schedule |

Current |

|

|

Estate Tax |

Mid-year revenue estimate exceeds initial revenue estimate |

Schedule |

Current |

|

|

KS |

PIT |

2.5% year-over-year revenue growth |

Formula |

Pending |

|

CIT Surtax |

2.5% year-over-year revenue growth (after PIT repeal) |

Formula |

Pending |

|

|

CIT |

2.5% year-over-year revenue growth (after surtaxes equalized) |

Formula |

Pending |

|

|

MA |

PIT |

2.5% inflation-adjusted year-over-year revenue growth |

Schedule |

Current |

|

MI |

PIT |

Inflation-adjusted revenue growth (statutory proportion) |

Formula |

Pending |

|

MO |

PIT |

GF revenue exceeds highest of past 3 years by $150M |

Schedule |

Pending |

|

NH |

CIT |

Combined GF & education trust fund revenue exceeds $4.64B |

Schedule |

Pending |

|

VAT |

Combined GF & education trust fund revenue exceeds $4.64B |

Schedule |

Pending |

|

|

NC |

CIT |

Revenue exceeds statutory benchmarks |

Schedule |

Current |

|

OK |

PIT |

Projections adequate to reduce rates on revenue-neutral basis |

Schedule |

Current |

|

OR |

PIT |

Revenue exceeds projections by at least 2% |

Refund |

Current |

|

VA |

Fuel Tax |

Absence of federal remote sales tax authority by given date |

Schedule |

Complete |

|

WV |

CIT |

Rainy Day Fund at 10% of budgeted GF revenue |

Schedule |

Complete |

Colorado

In Colorado, taxpayer refunds—though not permanent rate reductions—are enshrined in the state constitution via the state’s Taxpayer Bill of Rights (TABOR), which requires voter approval for tax increases and institutes refunds when state revenues exceed the rate of inflation and population growth. A voter-approved revision permits the state to retain excess revenue up to a cap designed to address a downward ratchet effect, whereby revenues recovering from an economic downturn could trigger a refund, even though revenues remained flat or even down over a multiyear period.

The state’s TABOR refund provisions are a tax trigger of sorts, but do not fit the narrower definition, inasmuch as they do not result in a sustained reduction in any tax rate. Colorado law spells out fifteen refund mechanisms, taken sequentially until surplus revenues are exhausted, including:

- A temporary reduction of the individual and corporate income tax rates from 4.63 percent to 4.5 percent in the subsequent tax year;

- A six-tier “sales taxA sales tax is levied on retail sales of goods and services and, ideally, should apply to all final consumption with few exemptions. Many governments exempt goods like groceries; base broadening, such as including groceries, could keep rates lower. A sales tax should exempt business-to-business transactions which, when taxed, cause tax pyramiding. refund,” which is actually distributed by formula through the individual income tax;

- The activation of the state’s Earned Income Tax Credit, which is only available in years with adequate TABOR refunds;[2] and

- Twelve other credits, exemptions, reductions, and refunds triggered by achieving statutorily-defined threshold amounts.[3]

The Colorado TABOR limits the growth of government and provides tax refunds, but it does so in a complex and unpredictable way. The state funnels tax refunds through any of fifteen mechanisms—and only in certain years—rather than using some portion of revenue growth to pay down permanent reductions in tax rates, thus foregoing much of the benefit associated with more predictable reductions in tax liability.

District of Columbia

In 2014, the District of Columbia approved a tax reform package which reduced corporate and individual income tax rates, adopted more generous standard deductions and personal exemptions, and expanded the Earned Income Tax Credit, among other changes. Additional tax reform priorities were made contingent upon midyear annual revenue estimates exceeding preliminary annual revenue estimates, with any additional monies in fiscal years 2015 and 2016[4] funneled into implementation of as many as seventeen tax reform provisions, addressed in order of priority. Broadly speaking, these provisions can be summarized as:

- Reducing individual income tax rates across multiple brackets;

- Cutting the corporate income tax, known as the business franchise tax;

- Raising the estate taxAn estate tax is imposed on the net value of an individual’s taxable estate, after any exclusions or credits, at the time of death. The tax is paid by the estate itself before assets are distributed to heirs. threshold; and

- Increasing the standard deductionThe standard deduction reduces a taxpayer’s taxable income by a set amount determined by the government. It was nearly doubled for all classes of filers by the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) as an incentive for taxpayers not to itemize deductions when filing their federal income taxes. and personal exemption.[5]

Rather than using triggers to reduce tax rates gradually in the out years, the District of Columbia’s tax plan conditions a portion of the tax cuts intended for implementation over a two-year period on rising revenue projections. Triggers are used, essentially, to determine the size and scope of intended cuts—their extent driven by revenue availability—rather than to phase in planned reductions over time.

Kansas

In 2013, Kansas adopted a substantial—and highly controversial—package of tax cuts, which were severed from corresponding spending reductions during legislative deliberation. In addition to steep initial cuts,[6] the tax package also contained a series of triggers for further reductions. In 2015, the trigger mechanisms were revised and the trigger dates moved back to accommodate the failure of adequate revenue to materialize.[7]

As currently structured, implementation of tax triggers is scheduled to begin on or after fiscal year 2020. Upon commencement of the triggers package, in any year when general fund receipts, less payments to the state retirement system, exceed the previous year’s receipts by at least 2.5 percent, the treasurer is to calculate the amount of tax rate reduction made possible by the additional revenue and apply the reduced rates to the next tax year, proceeding tax by tax in the following order:

- Individual income tax eliminated;

- SurtaxA surtax is an additional tax levied on top of an already existing business or individual tax and can have a flat or progressive rate structure. Surtaxes are typically enacted to fund a specific program or initiative, whereas revenue from broader-based taxes, like the individual income tax, typically cover a multitude of programs and services. on corporations reduced to the point that, when combined with the corporate income tax, the aggregate rate is at or below the combined corporate income tax and surtax imposed on banking institutions;

- Surtaxes on corporations, banking institutions, and trust companies reduced proportionately until wholly eliminated;

- Normal taxes on corporations, banking institutions, and trust companies reduced proportionately.

By pegging triggers to year-over-year revenue growth, without regard to any static baseline, Kansas could trigger tax cuts without any meaningful economic growth, a critical drawback. For instance, if revenues declined by 3 percent in year one and then recovered in year two, two-year revenue growth could be flat, but year-over-year growth would be sufficient to trigger a tax cut. Conversely, if revenue grew by 2 percent every year for a decade, no tax cuts would ever be triggered.[8]

Massachusetts

In 2000, Massachusetts voters ratified a phase-in of tax cuts designed to reduce the state’s individual income tax rate from 5.95 to 5.0 percent over three years,[9] but the reductions were frozen by the legislature in 2002 at a rate of 5.3 percent. As a compromise, the legislature agreed to allow further reductions to a 5.0 percent rate to proceed, but only after a series of increases to the personal exemption had been implemented, and at a pace of 0.05 percent per year, contingent upon state tax revenues having grown at least 2.5 percent faster than the rate of inflation. The legislature also dictated that revenue growth must be against the baseline, meaning that any midyear legal or administrative changes would be factored out of the calculation, and that revenue growth must be sustained for each of three consecutive quarters, relative to the corresponding quarter in the prior fiscal year.[10]

Under the 2002 law, the resumption of tax cuts could have begun as early as 2008, but due to the recessionA recession is a significant and sustained decline in the economy. Typically, a recession lasts longer than six months, but recovery from a recession can take a few years. , the state did not begin attaining benchmarked revenue goals until 2011, triggering a reduction to 5.25 percent for the 2012 tax year. A cut was not triggered in 2013,[11] but further reductions have followed in each subsequent year, with the tax rate standing at 5.1 percent as of 2016.[12]

Michigan

As part of a larger tax reform package enacted in 2015, which increased fuel taxes and expanded property taxA property tax is primarily levied on immovable property like land and buildings, as well as on tangible personal property that is movable, like vehicles and equipment. Property taxes are the single largest source of state and local revenue in the U.S. and help fund schools, roads, police, and other services. credits for low- and moderate-income taxpayers, Michigan is set to begin implementing income tax reductions beginning in fiscal year 2023.[13] Although several states have delayed implementation until several years after enactment, Michigan’s eight-year deferral is unusual in its length.

Following any year in which there is inflation-adjusted general fund/general purpose revenue growth, the individual income tax rate is to be reduced by an amount calculated by an equation which captures a portion of cumulative inflation-adjusted revenue growth over fiscal year 2021 collections. The income tax rate would be reduced proportionately by the amount which the prior year’s general fund revenue exceeded inflation-adjusted fiscal year 2021 revenue, multiplied by a statutorily set adjustment factor of 1.425 and divided by total income tax revenue.[14] Competing legislation would have utilized year-over-year revenue growth rather than a cumulative measure of inflation to trigger tax cuts.[15]

Missouri

As part of a modest package of tax reductions, Missouri legislators enacted a schedule of incremental individual income tax reductions, designed to reduce the top marginal rate from 6.0 percent to 5.5 percent over five or more years.[16] The legislation establishes rate reductions of 0.1 percent per year, contingent on the previous year’s net general revenue collections exceeding the highest amount of net general revenue collected in any of the three prior fiscal years by at least $150 million, beginning on or after 2017.[17] The first reduction will be delayed at least one year, since the state’s budget director has certified that revenue targets were not met.[18]

Missouri’s individual income tax currently features ten brackets, with the top marginal rate of 6.0 percent imposed on all income above $9,000. Achieving the 5.5 percent target rate would consolidate the top two rates, with the resulting top rate kicking in at $8,000 in current dollars. Beginning in 2017, bracket widths will also be adjusted for inflation.

New Hampshire

Resolution of a budget impasse in New Hampshire came when the governor and legislators agreed to subject a portion of legislatively-favored tax relief to a trigger mechanism to ensure revenue adequacy. The state’s business profits tax (a corporate income tax) was cut from 8.5 to 8.2 percent in 2016,[19] while the business enterprise tax (a value-added tax) rate declined from 0.75 percent to 0.72 percent. Subsequent reductions in 2018, however, will only proceed if the combined fiscal years 2016-2017 biennial unrestricted general and education trust fund revenues exceed $4.64 billion.[20]

Should this threshold be met, the business profits tax will fall to 7.9 percent, while the business enterprise tax further declines to 0.675 percent. Notably, the contingent second round of reductions can only be triggered in 2018. If biennial revenues do not meet the target amount, the current tax rates will remain in place indefinitely.

North Carolina

Spurred by an economic shift away from the state’s traditional manufacturing and agricultural sectors, North Carolina adopted comprehensive tax reform in 2013. That year’s legislation saw substantial individual income, corporate income, and sales tax reform, along with the repeal of the estate tax, relying on triggers for some of the corporate income tax reductions.[21]

The 2013 legislation cut the corporate income tax rate from 6.9 percent to 6.0 percent while broadening the tax base by reducing certain tax credits and exemptions, and scheduled a further reduction to 5.0 percent in 2014. Subsequent reductions, however, were made contingent on achieving statutorily-set revenue targets. Initially, the law established that if net general fund tax collections for the 2015 fiscal year exceeded $20.2 billion, the tax rate would be reduced by one percentage point, with a similar provision in place should revenue exceed $20.975 billion in fiscal year 2016.[22]

Notably, these changes did not have to be triggered sequentially. The rate would stand at 4.0 percent—a 1 percentage point reduction—both in a scenario where the first year but not the second year benchmark was achieved, and one where the state hit the second year target after falling short the first year. A reduction to 3.0 percent would, of course, require meeting or exceeding the established benchmarks in both years.

In 2015, after the first triggered reduction had been implemented, the General Assembly adopted further reforms, including an additional individual income tax rate reduction. Believing that these tax changes would delay reaching $20.975 billion in revenue, the legislature removed the timeline, stipulating that the second triggered reduction would be implemented whenever net general fund revenues exceeded the benchmark figure, whether in fiscal year 2016 or thereafter.[23] The adjustment notwithstanding, robust revenue growth has North Carolina on track to certify the 3.0 percent rate for the 2017 tax year.

Oklahoma

Oklahoma is in the process of individual income tax reductions culminating in a 4.85 percent rate, down from an initial rate of 5.25 percent. Reductions were designed to proceed in two stages, with an intermediate reduction to 5.0 percent in 2016 or the first year thereafter in which projected general revenues at a 5.0 percent rate exceeded projected general revenues for 2014.[24]

This threshold was met, and the second cut could be triggered in 2018 or any subsequent year should that year’s projected general fund revenues exceed the prior year projection by a sum sufficient to permit the rate cut on a revenue neutral basis or better. A decline in severance tax revenue as energy markets contract, however, may delay implementation of the tax cut’s second and final phase.

Most tax triggers rely on actual revenue, not projections. By relying exclusively on year-over-year general fund balance projections, triggers like those employed in Oklahoma have the potential to trigger tax cuts in a year when revenue declines unexpectedly. Conversely, by relying on fund balances, the Oklahoma triggers are susceptible to legislative gamesmanship, in which expenditures are pre-authorized or diverted to postpone an otherwise scheduled tax cut even in good years.[25] Although the use of revenue forecasts can permit a more prospective approach, they introduce greater uncertainty, particularly where current projections are compared to past projections, and not to actual revenues.

Oregon

Most tax triggers result in permanent rate reductions. Oregon, by contrast, provides refunds in the form of a tax credit in years subsequent to those in which biennial revenues exceed forecasted revenues by 2 percent or more.[26] An expenditure growth limitation measure more than a true tax trigger, the Oregon tax surplus credit, commonly known as the “kicker,” is designed to return excess revenue—which is to say, revenue beyond that which was anticipated and budgeted for—to the taxpayers, provided the excess is at least 2 percent above projection.[27]

Oregon’s “kicker” dates to 1979, but the method of refund has changed over the years. Through 1994, refunds were offered through tax credits, but from 1995 through 2011 they were issued as checks. Beginning with the 2012 tax year, the tax credits approach was readopted to reduce administrative costs.[28] The “kicker” is refundable, meaning that it can result in a refund if the amount exceeds a filer’s tax liability, but to claim it, the individual must have paid taxes the previous year.[29]

Because the credit is keyed to revenue over projection, and not year-over-year growth or revenue growth against some other baseline, it is possible for taxpayers not to receive a credit subsequent to years with considerable revenue growth (provided revenue projections anticipated that growth), and also possible for taxpayers to receive the “kicker” in years of economic contraction, so long as the revenue decline was not as steep as forecasters predicted. The effect of the tax credit is not to limit growth to a certain amount, but rather to return surpluses to the taxpayer, whatever expenditures were in a given year.

Virginia

A transportation funding plan adopted in 2013 contained what might be loosely construed as a tax trigger, though, unlike most triggers, this proposal contained a contingent provision for a tax increase. Among other changes, the legislation shifted a portion of infrastructure expenditures onto a sales tax increase and converted a motor fuel excise taxAn excise tax is a tax imposed on a specific good or activity. Excise taxes are commonly levied on cigarettes, alcoholic beverages, soda, gasoline, insurance premiums, amusement activities, and betting, and typically make up a relatively small and volatile portion of state and local and, to a lesser extent, federal tax collections. imposed at a rate of 17.5 cents per gallon into a 3.5 percent tax on the average wholesale price of gasoline.[30]

The legislation also anticipated additional revenue from sales taxes on remote transactions, and contained a contingent enactment clause for a provision stipulating that the rate would increase to 5.1 percent should Congress fail to enact the Marketplace Fairness Act or similar legislation permitting states to tax remote sales by 2015.[31] No such federal legislation has been enacted, triggering the motor fuel tax increase in January 2015.[32],[33]

West Virginia

In 2008, West Virginia embarked on a project of tax reform in an effort to reduce the state’s high and regionally uncompetitive business tax rates. At the time, the corporate income tax stood at 8.75 percent and a corporate franchise tax was imposed at a rate of 0.55 percent.

The franchise tax was set on a phase-down path, with the rate scheduled to decline each year before being repealed entirely as of the 2015 tax year.[34] This phase-down can be distinguished from tax triggers, because, while the reductions were implemented over time, the tax changes were not contingent upon meeting any benchmarks. Simultaneously, however, the legislature authorized a series of contingent reductions in the corporate income tax using tax triggers designed to ensure that the state maintained adequate reserves.[35]

Beginning with an immediate rate reduction from 8.75 percent to 8.5 percent for the 2009 tax year, the state committed to further reductions to 7.75 percent in 2012, 7.0 percent in 2013, and 6.5 percent in 2014,[36] with each reduction contingent on the combined balance in the state’s two rainy day funds[37] equaling or exceeding 10 percent of the budgeted general fund revenue for the subsequent fiscal year. Had rainy day fund balances fallen short of this benchmark in any given year, the entire schedule would have been pushed back one year. Ultimately, however, the state reached all of its targets, and the corporate income tax cuts went into effect on schedule.[38]

|

(a) Colorado’s TABOR only triggers temporary rate reductions in the year subsequent to revenue thresholds being exceeded. (b) The District of Columbia’s schedule of triggered reforms also includes a reduction in the rate of the new middle income bracket as well as increases to the personal exemption. (c) Kansas’s corporate income tax is generally represented as having a top rate of 7.0 percent, consisting of the 4.0 percent plus a 3.0 percent business surtax. The surtaxes on select business types can exceed 3.0 percent, and the state’s scheduled tax reductions anticipate reducing all surtaxes to 3.0 percent before reducing the remainder of the surtax and the corporate income tax in concert. (d) Michigan does not specify a final target rate, but rather permits continued rate reductions so long as revenues continue to meet targets. Kansas’s provisions are similar, but we indicate them as having a target of “full repeal” because triggers for each tax are delineated sequentially, such that the individual income tax must be repealed fully before business surtaxes are reduced to parity with corporate income taxes, at which time both surtaxes and corporate income taxes are to be cut in tandem up to full repeal. |

|||||

|

State |

Tax |

Initial |

Current |

Target |

Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

CO (a) |

PIT |

4.63% single rate |

4.63% single rate |

4.50% single rate |

Current |

|

DC (b) |

PIT |

8.95% > $350,000 |

8.95% > $1,000,000 |

8.95% > $1,000,000 |

Current |

|

CIT |

9.40% single rate |

9.20% single rate |

8.25% single rate |

Current |

|

|

Estate Tax |

$1 million exemption |

$2 million exemption |

$2 million exemption |

Current |

|

|

KS (c) |

PIT |

4.60% top rate |

4.60% top rate |

Full repeal |

Pending |

|

CIT Surtax |

Various rates (3%+) |

Various rates (3%+) |

Full repeal |

Pending |

|

|

CIT |

4.00% top rate |

4.00% top rate |

Full repeal |

Pending |

|

|

MA |

PIT |

5.30% |

5.10% |

5.00% |

Current |

|

MI (d) |

PIT |

4.25% |

4.25% |

Indefinite |

Pending |

|

MO |

PIT |

6.00% top rate |

6.00% top rate |

5.50% top rate |

Pending |

|

NH |

CIT |

8.20% |

8.20% |

7.90% |

Pending |

|

VAT |

0.75% |

0.75% |

0.675% |

Pending |

|

|

NC |

CIT |

5.00% |

4.00% |

3.00% |

Current |

|

OK |

PIT |

5.25% |

5.00% |

4.85% |

Current |

|

OR |

PIT |

9.99% top rate |

9.99% top rate |

Refund Credit |

Current |

|

VA |

Fuel Tax |

3.10% excise |

5.10% excise |

5.10% excise |

Complete |

|

WV |

CIT |

8.50% |

6.50% |

6.50% |

Complete |

Elements of Tax Trigger Design

States’ experimentation with a variety of frameworks for tax triggers permits comparisons, suggests various improvements, and facilitates at least a provisional sketch of best practices. Broadly speaking, there are four distinct design components of tax triggers: benchmarks, baselines, exclusions, and implementation mechanisms. Benchmarks are the thresholds that must be attained to trigger a tax change, while baselines are the ex-ante standard against which they are measured. Exclusions are any elements defined as existing outside of the benchmarks, and the implementation mechanism is the provision that gives force to the trigger, commencing the triggered reform.

Benchmarks

By definition, tax triggers involve the contingent implementation of planned tax policy changes subsequent to the state meeting established benchmarks, typically defined in terms of exceeding given revenue thresholds. How states define these thresholds, however, can vary substantially, and even subtle differences can influence trigger implementation.

Some states, like Kansas and Massachusetts, require a certain amount of year-over-year growth to trigger a tax reduction, rather than relying on growth against an established baseline. The potential shortcoming of relying on single-year revenue changes is that it can introduce a downward ratchet effect, where recovery from a year of revenue decline can trigger a tax cut even if revenue levels are stagnant or even down over a longer timeframe. If, for instance, qualified revenues declined from $10 billion to $9.5 billion in year one, then partially recovered to $9.8 billion in year two, the second year’s recovery would be adequate to trigger a tax cut contingent on 2.5 percent year-over-year revenue growth, even though revenues remain below their initial level.

Conversely, most other states set benchmarks that are impervious to such fluctuations. Some, like New Hampshire and North Carolina, established set revenue thresholds that must be attained before any tax reduction could be triggered, while Missouri sought to mitigate the effect of short-term revenue declines by requiring that general fund revenue exceed the highest level of the past three years by at least $150 million.

States may choose to establish a base year and then require revenues to exceed its inflation-adjusted collections by a given amount as a condition of implementation, ensuring that the benchmark reflects actual revenue growth over the period established by trigger legislation. A particularly conservative approach could involve requiring revenues to exceed thresholds for successive years to ensure that revenue increases are sustained, and not the result of one year of strong revenue growth.

Benchmarks may be set in terms of nominal dollars or as percentage growth, and may optionally be adjusted for inflation. They may be serial (e.g., 2 percent growth in a given year) or cumulative (e.g., revenues at least 2 percent ahead of inflation-adjusted ex ante collections). For longer-term or open-ended triggers, a population adjustment may also be warranted, though such a provision is less pertinent for tax changes designed to be triggered over a small number of years. An optimal benchmark might rely on inflation-adjusted revenue growth measured as a percentage over an established baseline revenue figure, plus any exclusions designed to permit the state to retain a portion of new revenues.

Baselines

All benchmarks require a baseline, whether implicit or explicit. Triggers which specify discrete revenue targets have an implicit baseline, while those relying on some measure of percentage growth must establish one explicitly. In either case, however, the measure of revenue must be defined. General fund revenue is the most common measure, though some states include non-general fund revenue or favor a measure of all tax revenue, while Oklahoma, Oregon, and the District of Columbia use revenue projections rather than, or in concert with, actual collections.

The District of Columbia’s tax triggers compare mid-year revenue estimates to preliminary estimates to determine the scope of tax reforms to be undertaken in a given year. Oregon, which refunds surplus revenues to taxpayers, subtracts projected revenues (upon which budgets are based) from actual collections to determine the level of tax relief provided. Oklahoma, atypically, is predicated on year-over-year increases in projected (rather than actual) revenue, which has the potential to trigger tax cuts in a year featuring unanticipated revenue shortfalls.

While the District of Columbia offers an intriguing model for an appropriate use of revenue projections in tax triggers, most well-structured triggers rely on actual revenue collections for preceding years, avoiding the possibility that a mistaken—or possibly even politically-driven—estimate could result in implementation of tax cuts after a period of economic contraction.

Exclusions

Most tax triggers adopt some threshold requirement before revenue growth is adequate to activate any tax provisions, but states differ in whether a tax cut, once triggered, is designed to dedicate all or some portion of new revenue to tax relief. It is easiest to envision exclusions as separate from adjustments for inflation or population change, as these seek to maintain neutrality across years, whereas exclusions are intended to retain some portion of new revenue, after adjustments.

West Virginia’s corporate income tax trigger is predicated on the state’s rainy day fund standing at no less than 10 percent of budgeted general fund revenues, while Kansas’s pending triggers exclude payments to the state retirement system in calculating revenue growth. Oregon, which provides taxpayer refunds, ties them to surpluses rather than revenue growth, while the rate triggers in North Carolina were designed to permit the state to retain a portion of new revenues. Once Michigan’s triggers go into effect, they will return a formula-driven share of inflation-adjusted revenue growth to taxpayers in the form of rate reductions, while allowing the remainder to accrue to the public fisc.

Exclusions can establish that the state retains some percentage of additional revenues, rather than dedicating the full amount to tax relief. Similarly, they can require that rainy day funds or pensions be funded at certain levels, or exclude such deposits from measures of revenue growth. In some states, such provisions can contribute meaningfully to fiscal health, whereas in others—particularly for triggers implemented relatively quickly—they may be unnecessary.

Implementation Mechanisms

Benchmarks for tax triggers can be tied to specific years or left date indeterminate. A number of states, including Kansas and Oklahoma, along with the District of Columbia, require benchmarks to be met by a given date. Failure to achieve a benchmark on schedule could, in some states, derail remaining triggers. Conversely, under a 2015 revision to the state’s triggers, North Carolina established a specific revenue target with no expiration date, though legislators were confident that it would be achieved quickly.

Tax triggers linked to specific years risk forestalling long-term reform if benchmarks are not achieved in a single year, while the benchmarks established for open-ended triggers can erode in value over time. An ideal tax trigger design might avoid linking benchmarks to specific years, but employ inflation indexingInflation indexing refers to automatic cost-of-living adjustments built into tax provisions to keep pace with inflation. Absent these adjustments, income taxes are subject to “bracket creep” and stealth increases on taxpayers, while excise taxes are vulnerable to erosion as taxes expressed in marginal dollars, rather than rates, slowly lose value. and desired exclusions to ensure that legislative intent is preserved through the passage of time.

Finally, the tax reductions promulgated through triggers can be implemented by formula or according to a rate reduction schedule. Under the former technique, the amount of any reduction is calculated based on revenue availability—dedicating all or some portion of the revenue to tax cuts—while in the latter scenario, a specific plan of rate reductions is carried out as revenue availability permits. Michigan, for instance, will calculate the size of future tax cuts based on a statutorily-established proportion of inflation-adjusted revenue growth, while many other states, like West Virginia, reduce rates by a given amount each year in which revenue targets are met. Either approach can be effective within a well-designed tax trigger framework.

Criticisms of Tax Triggers

Most criticisms of the use of tax triggers can be distilled into the critique leveled by Michael Leachman of the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, who noted that “[i]f you have a tax based on a blind formula, that formula doesn’t know when the next recession might hit or when another need might arise in the state.”[39] This observation, while true, is equally true of all tax rates, since unchanging rates are similarly unable to respond to recessions or revenue needs. This is, ultimately, the responsibility of legislators, who retain the ability to postpone or reverse triggered tax cuts, just as they have the ability to raise taxes in other circumstances.

Opponents do, however, raise valuable points in their critique of triggers which rely on poor measures of revenue adequacy, failing to establish a meaningful baseline or setting benchmarks which measure growth poorly. Relying exclusively on revenue forecasts (the approach embodied by the Oklahoma triggers) or leaning on year-over-year revenue changes without establishing a baseline (as Kansas intends) represent mistakes to be avoided. Frequently, criticisms of tax triggers are focused on these specific approaches.[40] Tax triggers are intended to promote certainty and ensure revenue stability through a program of incremental tax reforms, and poor structures can undermine these goals.

Notably, critiques of tax triggers tend to center on poorly-structured triggers, rather than the concept itself. Well-designed triggers introduce greater flexibility and responsiveness into the tax code, while codifying a commitment to improving tax policy, offering a prudent way to address any uncertainties during the implementation of tax reform measures.

Distinguishing Tax Triggers from Tax and Expenditure Limitations

Although tax triggers are indisputably an instrument of tax limitation, they tend to be distinct from an older concept, tax and expenditure limitations (TELs), which impose caps on appropriations or, in limited cases, revenues. The earliest TELs were often devised as property tax limitations, including the initiative that sparked the “taxpayer revolt” of the late 1970s and early 1980s, California’s Proposition 13. Over time, states began to adopt similar provisions restricting tax and revenue growth more generally.[41]

Twenty-eight states currently have tax and expenditure limitations in place,[42] but with limited exceptions, evidence of their effectiveness is slight.[43] Most studies find that their provisions are easily circumvented,[44] and empirical studies rarely show any statistically significant effect on revenue or expenditure growth.[45]

Several TELs restrict revenues through the budget process, for instance by limiting budgeted revenues to a certain percentage of state personal income. Procedures vary when revenue projections under existing tax regimes exceed limitation formulas, with requirements ranging from depositing surplus revenues into a rainy day fund to providing taxpayer refunds or rebates for the excess amount.[46]

Unlike true tax triggers, TELs do not result in permanent changes in tax rates or structure, at most initiating a tax refund or temporarily lower rate. As such, they generally lack the effectiveness or significance of tax triggers. Nevertheless, a few state provisions which can most properly be understood as TELs, including the Colorado Taxpayer Bill of Rights, contain provisions for automatic reductions of tax liability and blur the lines between TELs and tax triggers, hence their inclusion in the scope of this paper.

Conclusion

Well-structured tax triggers help states phase in tax reform while ensuring revenue stability. As such, they are a valuable tax reform tool, addressing concerns about revenue maintenance or offering greater revenue certainty even in scenarios where revenue cuts are desired. Not all rate reductions require triggers, but the assurances they provide can be very attractive.

Just as notable as the implementation of tax cuts using tax triggers is that trigger mechanisms have, in fact, postponed tax reductions in cases where revenue failed to exceed benchmarks—examples of triggers working effectively just as much as when they phase in tax relief.

As with the tax reform provisions they can help implement, the effectiveness of tax triggers depends on their design. All frameworks for contingent implementation of tax reform are not alike, and prudence demands that policymakers carefully consider which benchmarks, baselines, exclusions, and implementation mechanisms are appropriate to the circumstances, rather than treating all tax triggers as interchangeable, or regarding them as an afterthought in tax reform considerations.

Well-designed triggers specify baseline revenues and adjust benchmarks for inflation, or, if of a shorter duration, set out specific revenue figures as benchmarks. Optimally, triggers are not constrained to a particular year or years, but rather permit tax reforms to be phased in over time as inflation-adjusted revenue targets are met. They may also reserve some portion of revenue growth to rainy day and pension funds, or permit a share of it to accrue to the state as additional unrestricted revenue. Such an approach may have particular value if reductions are indefinite and open-ended, continuing whenever revenues warrant, rather than culminating in a statutorily-established final rate.

When care is taken in their design, tax triggers are increasingly proving a highly valuable tool for those seeking tax reform coupled with revenue stability. As additional states turn to tax triggers as a component of tax reform plans, there is every opportunity to learn from the examples of the states which have already adopted such measures, and to develop triggers that incorporate best practices gleaned from them.

[1] A brief discussion of how older tax and expenditure limitation (TEL) regimes differ from tax triggers can be found later in this paper. Budgetary provisions that permit but do not require refunds or temporary rate reductions, like Ohio’s Income Tax Reduction Fund program, are excluded from this analysis.

[2] C.R.S.A. §§ 39-22-627, 39-22-120, and 39-22-123.5.

[3] Kate Watkins, “TABOR Refund Mechanisms,” Colorado Legislative Council Staff Memorandum, Jan. 4, 2009, https://www.colorado.gov/pacific/sites/default/files/TABOR%20Refund%20Mechanisms%20-%20Descriptions%20and%20Prioritization.pdf, 5.

[4] Less the first $181 million in additional projected revenue in FY 2015, which was to be recognized as FY 2016 revenue.

[5] DC ST § 47-181.

[6] Kansas’s tax cut package also exempted pass-through income from all income taxation, narrowing the tax base and creating new opportunities for tax arbitrage. See, e.g., Scott Drenkard, “Kansas’ Pass-Through Carve-Out: A National Perspective,” Testimony, Kansas House Committee on Taxation, Mar. 15, 2016, https://taxfoundation.org/article/kansas-pass-through-carve-out-national-perspective.

[7] 2015 Kansas Laws Ch. 99 (H.B. 2109).

[8] K.S.A. § 79-32,269.

[9] Massachusetts Secretary of the Commonwealth’s Office, “The Official Massachusetts Information for Voters: The 2000 Ballot Questions,” 2000, https://www.sec.state.ma.us/ele/elepdf/IFV2000.pdf, 8-9.

[10] M.G.L.A. 62 § 4.

[11] Michael Norton, “Massachusetts State Income Tax Cut Scheduled for Jan. 1 Won’t Happen,” [Massachusetts] State House News Service, Nov. 15, 2012, http://www.masslive.com/politics/index.ssf/2012/11/massachusetts_state_income_tax.html.

[12] Nicole Kaeding, “State Individual Income Tax Rates and Brackets for 2016,” Tax Foundation Fiscal Fact No. 500, Feb. 8, 2016, https://taxfoundation.org/article/state-individual-income-tax-rates-and-brackets-2016.

[13] State of Michigan, Act No. 180 [S.B. 414], Public Acts of 2015, 98th Legislature, Regular Session of 2015, Nov. 10, 2015.

[14] M.C.L.A. 206.51.

[15] Michigan House Fiscal Agency, “Road Funding Package – Preliminary Analysis,” Nov. 3, 2015, http://www.legislature.mi.gov/documents/2015-2016/billanalysis/House/pdf/2015-HLA-4370-F222A839.pdf.

[16] Like Kansas, Missouri also made changes to the treatment of pass-through income, though Missouri offered a 25 percent deduction (once fully phased in) rather than a complete exemption. See, e.g., Scott Drenkard, “Missouri’s 2014 Tax Cut: Minimal and Slow with a Small Business Gimmick,” Tax Foundation Fiscal Fact No. 431, May 14, 2014, https://taxfoundation.org/article/missouri-s-2014-tax-cut-minimal-and-slow-small-business-gimmick.

[17] V.A.M.S. 143.011.

[18] Maria Koklanaris, “Missouri Income Tax Cuts on Hold After State Misses Revenue Targets,” State Tax Notes, July 6, 2016, http://www.taxnotes.com/state-tax-today/individual-income-taxation/missouri-income-tax-cuts-hold-after-state-misses-revenue-targets/2016/07/06/18533981.

[19] N.H. Rev. Stat. § 77-A:2

[20] N.H. Rev. Stat. § 77-E:2.

[21] Liz Malm, “North Carolina House, Senate, and Governor Announce Tax Agreement,” Tax Foundation Tax Policy Blog, July 15, 2013, https://taxfoundation.org/blog/north-carolina-house-senate-and-governor-announce-tax-agreement.

[22] General Assembly of North Carolina, North Carolina Session Laws 2013-316 (H.B. 998).

[23] N.C.G.S.A. § 105-130.3C.

[24] 68 Okl. St. Ann. § 2355.1F-G.

[25] Scott Drenkard, “Keep an Eye on the Trigger Mechanism in Oklahoma’s Tax Cut,” Tax Foundation Tax Policy Blog, May 13, 2014, https://taxfoundation.org/blog/keep-eye-trigger-mechanism-oklahoma-s-tax-cut.

[26] Since 2012, surplus revenue from the corporate income tax has been excluded, and is instead deposited in the State School Fund. See Oregon Department of Revenue, “2015 Kicker Credit,” http://www.oregon.gov/DOR/press/Documents/kicker_fact_sheet.pdf, 2.

[27] O.R.S. § 291.349.

[28] Oregon Department of Revenue, “2015 Kicker Credit.”

[29] OAR 150-291.349.

[30] Virginia General Assembly, H.B. 2313 of 2013.

[31] Id.

[32] Jenna Portnoy, “Va. Gas TaxA gas tax is commonly used to describe the variety of taxes levied on gasoline at both the federal and state levels, to provide funds for highway repair and maintenance, as well as for other government infrastructure projects. These taxes are levied in a few ways, including per-gallon excise taxes, excise taxes imposed on wholesalers, and general sales taxes that apply to the purchase of gasoline. Set to Increase After Congress Fails to Pass Online Sales Tax Bill,” The Washington Post, Nov. 27, 2014, https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/virginia-politics/va-gas-tax-set-to-increase-after-congress-fails-to-pass-online-sales-tax-bill/2014/11/27/609952ea-74fa-11e4-9d9b-86d397daad27_story.html.

[33] Several other states, including Wisconsin, committed to contingent individual income tax rate reductions had Congress adopted the Marketplace Fairness Act or something substantially similar during the 2013-2015 biennial budget period. These may be considered a class of tax trigger, but they have since expired without implementation. See, e.g., Paul Demery, “Wisconsin would cut income taxes if a federal online sales tax law passes,” Internet Retailer, July 2, 2013, https://www.internetretailer.com/2013/07/02/wisconsin-would-cut-income-if-us-online-sales-tax-law-passes.

[34] W. Va. Code, § 11-23-6.

[35] Elia Peterson and Liz Malm, “West Virginia to Reduce Corporate Income Tax Rate,” Tax Foundation Tax Policy Blog, Oct. 3, 2013, https://taxfoundation.org/blog/west-virginia-reduce-corporate-income-tax-rate.

[36] W. Va. Code, § 11-24-4.

[37] The Revenue Shortfall Reserve Fund, from which the governor may borrow funds to make timely payments during shortfalls and can be tapped by the legislature during fiscal crises, and the Revenue Shortfall Reserve Fund—Part B, which may only be used in fiscal emergencies, and only after all monies in the former account have been expended. See West Virginia State Budget Office, “About the Rainy Day Fund,” http://www.budget.wv.gov/reportsandcharts/Pages/default.aspx#AboutRainy.

[38] Lyman Stone, “West Virginia Reduces Franchise Tax, Corporate Income Tax,” Tax Foundation Tax Policy Blog, Jan. 22, 2014, https://taxfoundation.org/blog/west-virginia-reduces-franchise-tax-corporate-income-tax.

[39] Elaine Povich, “ ‘Triggers’ Cut State Taxes; But Are They Good Policy?” Stateline, The Pew Charitable Trusts, Nov. 16, 2015, http://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/blogs/stateline/2015/11/16/triggers-cut-state-taxes-but-are-they-good-policy.

[40] See, e.g., Norton Francis, “Oklahoma Pulls the Trigger on an Unaffordable Tax Cut,” Tax Policy Center, Jan 5, 2015, http://www.taxpolicycenter.org/taxvox/oklahoma-pulls-trigger-unaffordable-tax-cut.

[41] Steven Deller and Judith Stallmann, “Tax ExpenditureTax expenditures are a departure from the “normal” tax code that lower the tax burden of individuals or businesses, through an exemption, deduction, credit, or preferential rate. Expenditures can result in significant revenue losses to the government and include provisions such as the earned income tax credit (EITC), child tax credit (CTC), deduction for employer health-care contributions, and tax-advantaged savings plans. Limitations and Economic Growth,” Marquette Law Review, 90:497 (2007): 497-500.

[42] National Association of State Budget Officers, “Budget Processes in the States,” Spring 2015, http://www.nasbo.org/sites/default/files/2015%20Budget%20Processes%20-%20S.pdf, 61-64.

[43] See, e.g., Matthew Mitchell, “T.E.L. It Like It Is: Do State Tax and Expenditure Limits Actually Limit Spending?” Mercatus Center at George Mason University Working Paper No. 10-71, Dec. 2010, http://mercatus.org/sites/default/files/publication/TEL%20It%20Like%20It%20Is.Mitchell.12.6.10.pdf.

[44] See, e.g., Joseph Mengedoth and Santiago Pinto, “Show and TEL: Are Tax and Expenditure Limitations Effective?” Econ Focus, 19, no. 2 (2015): 36-39.

[45] Benjamin Zycher, “State and Local Spending: Do Tax and Expenditure Limits Work?,” American Enterprise Institute, May 2013, http://www.aei.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/-state-and-local-spending-do-tax-and-expenditure-limits-work_152855963641.pdf, 3.

[46] See, e.g., National Association of State Budget Officers, “Budget Processes in the States,” 61-62.