Key Findings

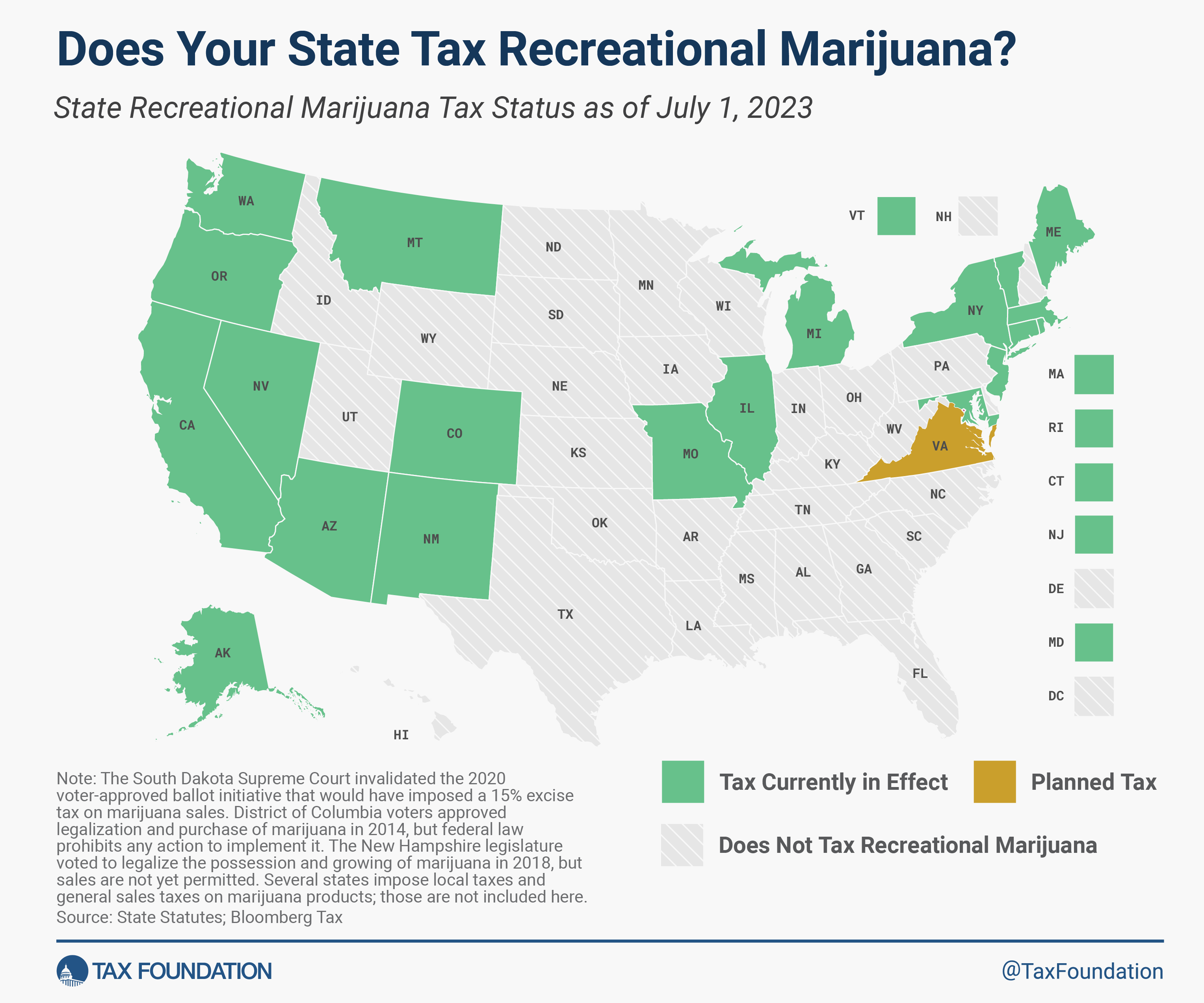

- Twenty-one states now taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. recreational marijuana (also known as cannabis)—Alaska, Arizona, California, Colorado, Connecticut, Illinois, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Missouri, Montana, Nevada, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, Oregon, Rhode Island, Vermont, Virginia, and Washington.

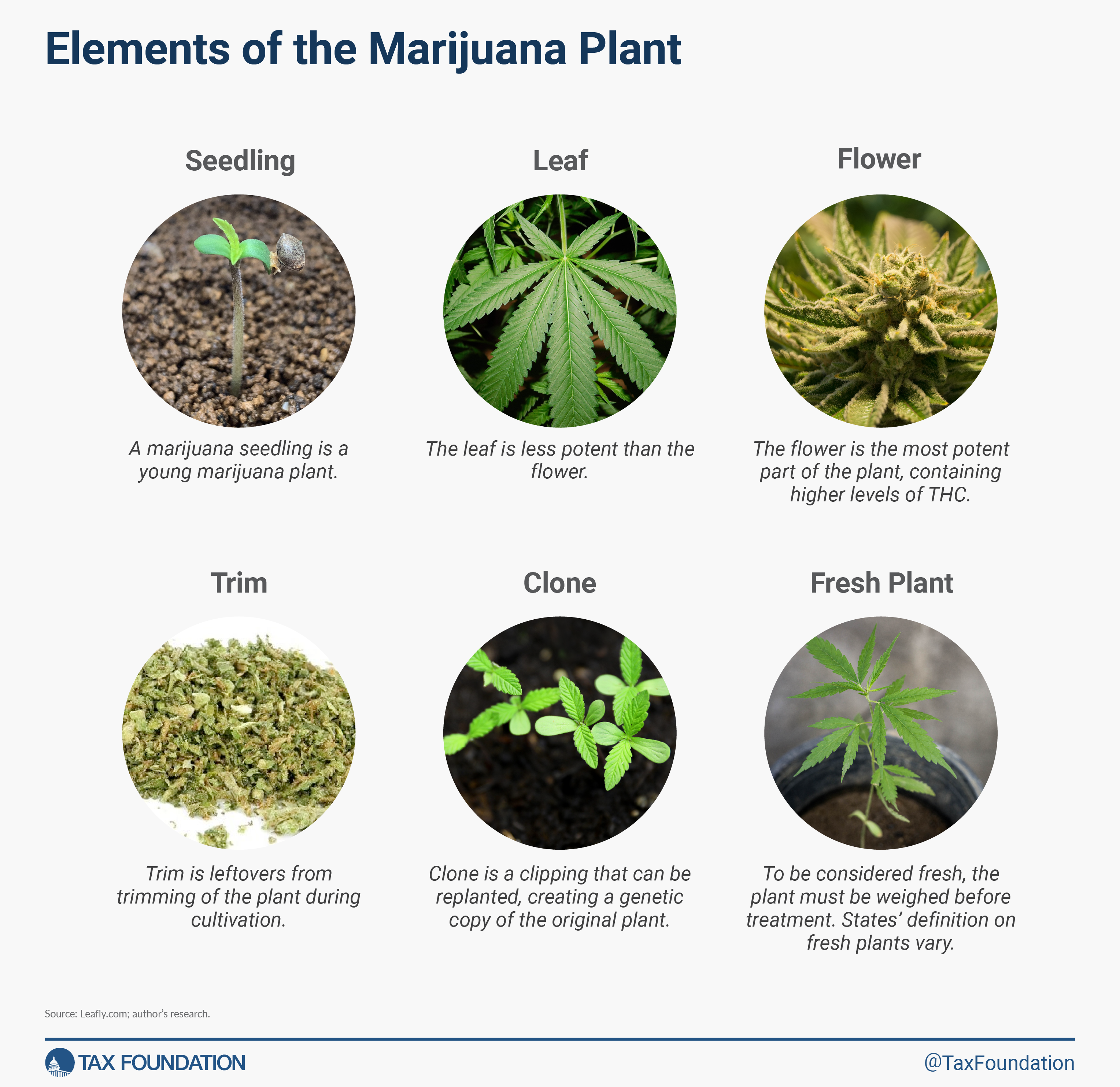

- The unique issues raised by cannabis taxation created a wide variety of tax designs. These include ad valorem rates applied at the wholesale and retail levels, and ad quantum taxes levied separately on cannabis seeds, flower (mature and immature), leaves, trim, clones, whole plants, concentrates, and edibles. These rates can vary by tetrahydracannibol (THC) content in the product.

- The experience of taxed legal cannabis markets demonstrates that tax rates should be low enough to allow legal markets to undercut, or at least gain price parity with, the illicit market.

- The revenue potential from cannabis is substantial. States collected nearly $3 billion in marijuana revenues in 2022. Nationwide legalization could generate $8.5 billion annually for all states.

- Tax consistency across jurisdictions will be important if interstate commerce is legalized.

- Potency-based taxation is ideal. Until testing becomes less costly, however, a weight-based tax or a hybrid weight-based tax based on a limited number of potency categories is the most effective tax design.

Introduction

Marijuana taxation is one of the hottest policy issues in the United States. Twenty-one states have implemented legislation to legalize and tax recreational marijuana sales: Alaska, Arizona, California, Colorado, Connecticut, Illinois, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Missouri, Montana, Nevada, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, Oregon, Rhode Island, Vermont, Virginia, and Washington.

Marijuana markets operate under a unique legal framework. Federally, marijuana is classified as a Schedule I substance under the Controlled Substances Act, making the drug illegal to consume, grow, or dispense. States that have legalized consumption and distribution do not actively enforce the federal restrictions.

Among the many effects this creates, each state market becomes a silo. Marijuana products cannot cross state borders, so the entire process (from seed to smoke) must occur within a single state. This unusual situation, along with the novelty of legalization, has resulted in a wide variety of tax designs.[1]

In this paper, we explore cannabis taxation. We discuss why marijuana should be taxed and the various strengths and weaknesses of different tax designs. We then analyze lessons learned from recreational marijuana taxes across the U.S. states. Several of these lessons can inform tax reform in states that already tax recreational cannabis and help form a blueprint for both the adoption of taxes in other states and federal policy. We conclude with a summary of best practices for marijuana taxation.

What Is Cannabis and Why Tax It?

Marijuana is derived from the cannabis sativa or hemp plant. Cannabis sativa has long been an agricultural crop grown across the United States for use as industrial hemp. There are more than 25,000 different products that use industrial hemp across a variety of sectors.[2] Marijuana plants differ from industrial hemp not only in look but also in the amount of THC present in the plant.

THC is the main psychoactive compound and is generally used to define the potency of the marijuana product, even though other compounds in the plant may influence the user. Industrial hemp generally has less than 0.3 percent THC, whereas marijuana plants contain substantially higher levels. Marijuana material prepared from the flowering tops or leaves usually contains 0.5–5.0 percent THC and cannabis plants grown under controlled hydroponic conditions generally contain 9-25 percent THC.[3]

The marijuana plant has several components, each with varying qualities, THC potency, and uses. Separate markets have developed for the plant to be sold in different stages of development depending on the intended use by the consumer. Some of the most popular elements of the marijuana plant are illustrated in Figure 1.

Marijuana is intoxicating, causing behavioral changes and potential long-term negative health effects. These characteristics prompted its prohibition and, where legalized, product-specific “sin” excise taxes. Marijuana intoxication is dose-related, and the amount absorbed by the body varies by the route of administration and the concentration of the source being used.[4] Marijuana is commonly smoked due to the rapid onset of symptoms, but marijuana can also be eaten (e.g., brownies) or drunk (e.g., marijuana tea).

The academic literature on cannabis is very young, without a consensus on the external harms of cannabis consumption. This lack of consensus increases the difficulty of identifying a socially optimal tax design.

Cannabis Tax Designs

The design of an excise taxAn excise tax is a tax imposed on a specific good or activity. Excise taxes are commonly levied on cigarettes, alcoholic beverages, soda, gasoline, insurance premiums, amusement activities, and betting, and typically make up a relatively small and volatile portion of state and local and, to a lesser extent, federal tax collections. is important. Well-designed taxes generate revenue with far less societal impact than poorly designed taxes.

Perhaps the closest markets from which to mirror public policy for cannabis are the well-established taxes on alcohol and tobacco. However, cannabis markets have not evolved a standardized product like tobacco, where taxes can be levied by stick (cigarette) or pack, nor is the intoxicating ingredient (THC) as easily measured as alcohol content for an appropriately targeted tax.

The resulting tax landscape is chaotic, lacking an academically supported consensus foundation for tax policy. Certain states apply specific taxes, others apply ad valorem taxes, and some states apply a hybrid approach that uses both.

Price

Ad valorem taxes add a percentage tax to the price of a transaction. Price-based taxes can be applied at any location in the supply chain, but are most commonly applied to either wholesale transactions or retail sales.

The most attractive feature of price-based taxes is that they are relatively simple to administer. Forty-five states already administer a general sales taxA sales tax is levied on retail sales of goods and services and, ideally, should apply to all final consumption with few exemptions. Many governments exempt goods like groceries; base broadening, such as including groceries, could keep rates lower. A sales tax should exempt business-to-business transactions which, when taxed, cause tax pyramiding. , and cannabis can simply be added to the existing tax baseThe tax base is the total amount of income, property, assets, consumption, transactions, or other economic activity subject to taxation by a tax authority. A narrow tax base is non-neutral and inefficient. A broad tax base reduces tax administration costs and allows more revenue to be raised at lower rates. . A separate excise tax is somewhat more administratively costly, but not much. In those states, the infrastructure and procedural systems are already in place for price-based tax collections and remissions. The compliance costs associated with incorporating another ad valorem tax are marginal.

Price-based taxes also capture a relatively consistent percentage of overall spending in the market. The rates do not need to be adjusted for inflationInflation is when the general price of goods and services increases across the economy, reducing the purchasing power of a currency and the value of certain assets. The same paycheck covers less goods, services, and bills. It is sometimes referred to as a “hidden tax,” as it leaves taxpayers less well-off due to higher costs and “bracket creep,” while increasing the government’s spending power. or for most changes in consumer behavior.

Price-based taxes result in higher tax payments on more expensive products, generally—but imperfectly—resulting in higher payments for (presumably higher-priced) more potent and premium products that are more commonly purchased by consumers with higher incomes.

Price-based taxes have two major drawbacks. First, from a theoretical perspective, the social harms of cannabis consumption aren’t caused by the price of the product, but rather by the quantity of the product consumed. While price and quantity are related, a poorly targeted tax runs the risk of failing to accomplish its goals (both raising revenue and marginally deterring consumption) if market dynamics shift.

Second, revenue from ad valorem taxes can be highly volatile. In a market system, prices rapidly adjust to changing market conditions. As prices adjust, so would any tax revenues tied to those prices.

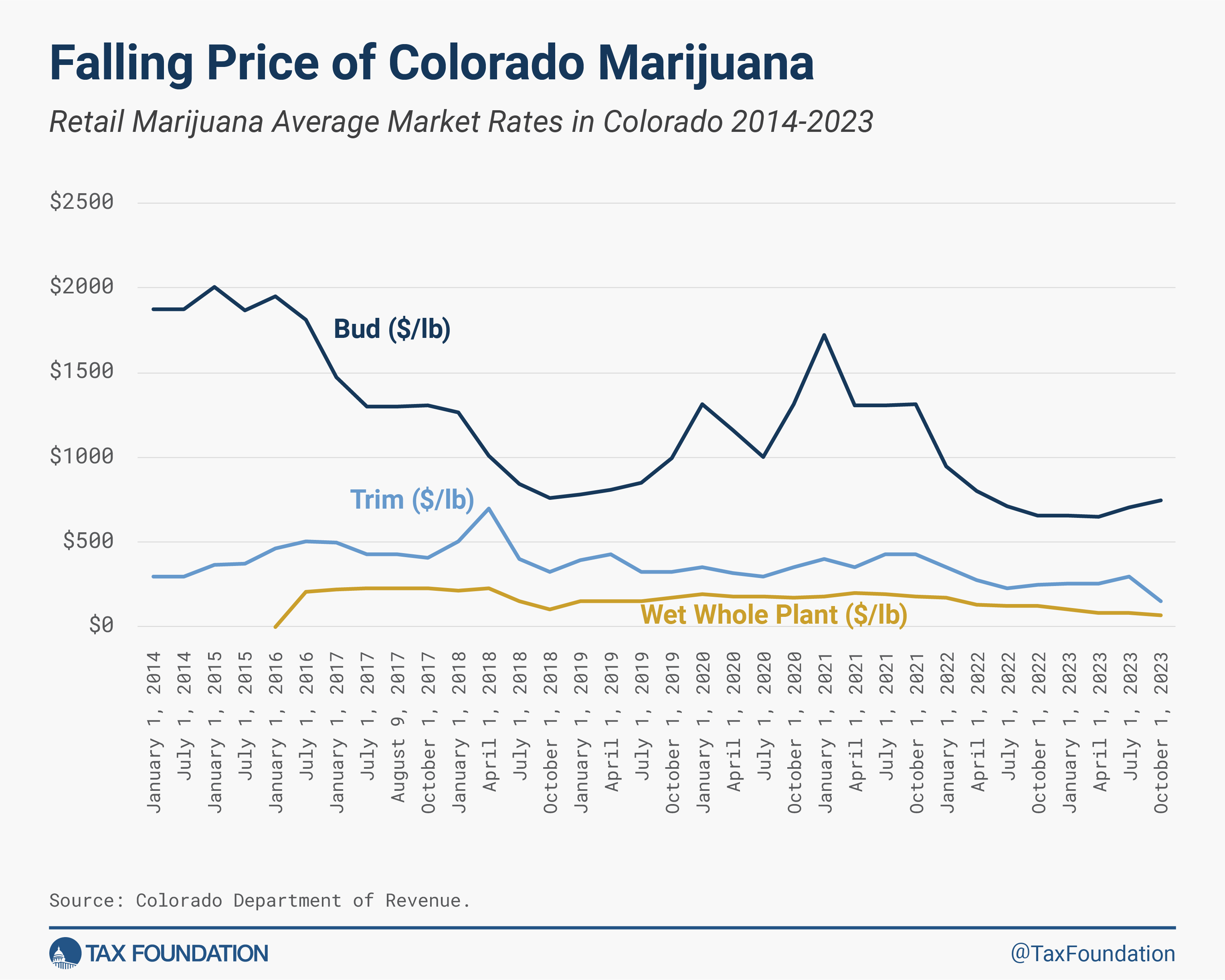

Cannabis markets have experienced sizable shifts in the past decade. As legal cannabis markets matured, so did growing operations. Suppliers entered the market and have been able to scale their operations with time. The result has been a steady decline in price after a market has been established for a few years. If cannabis were legalized nationally, ending the prohibition on interstate sales, prices would be expected to drop even more precipitously.

Figure 2 shows the average retail price of marijuana products in Colorado for the past decade. At the start of 2014, the price for a pound of marijuana bud was $1,876. Over time, the prices steadily fell, reaching an all-time low for recorded legal sales price in April of this year, at $658.

Colorado levies two separate excise taxes on cannabis: 15 percent on the wholesale price and another 15 percent on the retail sales price. The entirety of the wholesale tax revenues are dedicated to the state’s fund for repairing and replacing Colorado’s most needy public school facilities, the Building Excellent Schools Today (BEST) fund. The retail excise tax revenue is shared between major programs for education, health care, human services, and corrections.

As the price of cannabis fluctuates, and in Colorado’s case falls substantially, so does funding for any programs tied to those revenue streams. The volatility of revenues from price-based excise taxes can be a significant drawback to their implementation.

Choosing whether to apply ad valorem taxes at the retail or wholesale level similarly involves weighing trade-offs. Taxes applied at the wholesale level require fewer tax remitters and generally have lighter compliance and administration costs. The major challenge to the effectiveness of wholesale taxes is tax avoidance by vertically integrated firms. A fully integrated firm that grows plants from seeds and possesses its product until the point of sale never truly sells the product as a wholesaler. If mandated to report an inter-company sale, the operator can avoid price-based taxes by selling the product internally at little or no price until the point of the retail sale.

When legal markets first opened in Colorado, for example, cannabis retailers were initially required to cultivate at least 70 percent of the cannabis they sold. The vertical integration made it difficult for tax authorities to enforce the state’s 15 percent wholesale price tax and resulted in regulators adopting a de facto weight-based system, in which cannabis “sold” at the wholesale level was subject to a tax based on a single estimated average price of cannabis, rather than on a “sale” price reported by the firm.[5]

Quantity or Weight

Specific ad quantum taxes can be simpler than ad valorem taxes because the tax can be calculated based on weight, volume, or quantity instead of requiring an estimated value of the product. Cigarette excise taxes are applied per pack and gasoline excise taxes are applied per gallon, for example.

The rule of thumb for excise taxes targeting harm-generating products is that the tax base should apply to the harm- or external-cost-causing element.[6] Targeting the harm-causing element best allows market participants to incorporate any external effects into their decision-making. Quantity-based taxes also help better align the tax base to the tax’s purpose than ad valorem taxes.

Weight-based taxes produce greater revenue stability than price-based taxes because aggregate consumption fluctuates less than market prices. Weight-based taxes also avoid the price-based challenges associated with vertically integrated companies.

Weight-based taxes have two significant disadvantages. First, weight-based taxes do not account for cannabis potency. A tax based on weight will incentivize the production of stronger cannabis to lower the tax paid per THC content. Product quality substitution, often called the “third law of demand,” is a problem that plagues excise taxation, as weight-based taxation incentivizes consumers to switch toward more potent or dangerous products.[7]

Weight-based systems can also be more burdensome for businesses and tax collectors. In 2022, California eliminated its weight-based cultivation tax and shifted the point of collection and remittance from distributors to retailers. This legislation received support from both the industry and legislators, with Governor Newsom promoting the changes in the state’s budget by saying, “These policy changes aim to greatly simplify the tax structure, remove unnecessary administrative burdens and costs, temporarily reduce the tax rate to support shifting consumers to the legal market, and stabilize the cannabis market with policies that are more transparent and can better adjust to market changes.”[8]

Potency

On paper, taxing marijuana based on THC content could be the most effective tax design because it most directly captures the externalityAn externality, in economic terms, is a side effect or consequence of an activity that is not reflected in the cost of that activity, and not primarily borne by those directly involved in said activity. Externalities can be caused by either the production or consumption of a good or service and can be positive or negative. associated with consumption. As referenced earlier, however, taxing cannabis based on THC content is more difficult than taxing alcoholic beverages by alcohol content.

Reliable and cost-effective potency-based testing remains a significant barrier, particularly for raw plant material. Testing consistency still varies across labs and a sizable percentage of product is destroyed during the testing process.

A 2020 study estimated the cost of testing compliance in California markets.[9] The equipment and startup costs for a new lab exceeded $1.5 million and the annual costs of operations, maintenance, and salaries required more than $1 million.

The authors found an average testing cost of $136 per pound of dried cannabis flower. That amounts to about 10 percent of the 2019 average wholesale price or about 14 percent of the September 2023 wholesale price.

To date, three states—Connecticut, Illinois, and New York—incorporate THC content into their tax regimes. Lessons from these and other states provide valuable information for tax policy across all U.S. States and for potential federal legislation.

Lessons from Cannabis Taxation in U.S. States

With the addition of Missouri and Maryland in 2022, 21 states have implemented legislation to legalize and tax recreational marijuana sales. The map below highlights state tax policy on recreational marijuana.

The unique treatment of cannabis has resulted in a wide variety of tax designs.[10] Table 1 below illustrates the variety of tax policies implemented across the U.S. states.

State Marijuana Tax Rates, July 2023

| State | Tax Rate |

|---|---|

| Alaska | $50/oz. mature flowers; |

| $25/oz. immature flowers; | |

| $15/oz. trim, $1 per clone | |

| Arizona | 16% excise tax (retail price) |

| California | 15% excise tax (levied on wholesale at average market rate) |

| Colorado | 15% excise tax (levied on wholesale at average market rate); |

| 15% excise tax (retail price) | |

| 3% excise tax (retail price) | |

| Connecticut | $0.00625 per milligram of THC in plant material |

| $0.0275 per milligram of THC in edibles | |

| $0.009 per milligram of THC in non-edible products | |

| Illinois | 7% excise tax of value at wholesale level; |

| 10% tax on cannabis flower or products with less than 35% THC; | |

| 20% tax on products infused with cannabis, such as edible products; | |

| 25% tax on any product with a THC concentration higher than 35% | |

| Maine | 10% excise tax (retail price); |

| $335/lb. flower; | |

| $94/lb. trim; | |

| $1.5 per immature plant or seedling; | |

| $0.3 per seed | |

| Maryland | 9% excise tax (retail price) |

| Massachusetts | 10.75% excise tax (retail price) |

| Michigan | 10% excise tax (retail price) |

| Missouri | 6% excise tax (retail price) |

| Montana | 20% excise tax (retail price) |

| Nevada | 15% excise tax (fair market value at wholesale); |

| 10% excise tax (retail price) | |

| New Jersey | Up to $10 per ounce, if the average retail price of an ounce of usable cannabis was $350 or more; |

| up to $30 per ounce, if the average retail price of an ounce of usable cannabis was less than $350 but at least $250; | |

| up to $40 per ounce, if the average retail price of an ounce of usable cannabis was less than $250 but at least $200; | |

| up to $60 per ounce, if the average retail price of an ounce of usable cannabis was less than $200 | |

| New Mexico | 12% excise tax (retail price) |

| New York | $0.005 per milligram of THC in flower |

| $0.008 per milligram of THC in concentrates | |

| $0.03 per milligram of THC in edibles | |

| 13% excise tax (retail price) | |

| Oregon | 17% excise tax (retail price) |

| Rhode Island | 10% excise tax (retail price) |

| Virgina (a) | 21% excise tax (retail price) |

| Vermont | 14% excise tax (retail price) |

| Washington | 37% excise tax (retail price) |

Note: In Maryland, the state General Assembly passed a bill that would implement a rate of 9 percent. District of Columbia voters approved legalization and purchase of marijuana in 2014 but federal law prohibits any action to implement it. In 2018, the New Hampshire legislature voted to legalize the possession and growing of marijuana, but sales are not permitted. Alabama, Georgia, Idaho, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Minnesota, Nebraska, North Carolina, South Carolina, Oklahoma, Rhode Island, and Tennessee impose a controlled substance tax on the purchase of illegal products. Several states impose local taxes as well as general sales taxes on marijuana products. Those are not included here.

Sources: State statutes; Bloomberg Tax.

States apply a range of different policies. Ad valorem rates are applied at the wholesale and retail levels, ranging from 6 percent in Missouri (as a standalone tax, though ad valorem rates go as low as 3 percent in Connecticut, which applies a hybrid tax) to 37 percent in Washington. Specific taxes are levied separately on cannabis seeds, flower (mature and immature), leaves, trim, clones, whole plants, concentrates, and edibles, and can vary by THC content in the product.

Several important lessons emerged from the rollout of marijuana laws and the adoption of legal markets.

1. When designing the tax, rates should be low enough to allow legal markets to undercut, or at least gain price parity with, the illicit market.

Identifying the social costs of marijuana consumption is difficult because the academic literature on the topic is very young, and because some costs would be reduced by legalization. Current research estimates suggest that cannabis, where legal and taxed, is often overtaxed, preventing legal markets from capturing more of the market activity that happens in black markets.[11]

2. The revenue potential from legal marijuana markets is significant. These revenues may take years to materialize after legalization, however, and revenues will be volatile, particularly if taxes are levied ad valorem instead of ad quantum.

Table 2 summarizes the marijuana tax revenues (recreational plus medical) collected by states in 2022. The table also presents an estimated tax potential for states using the average revenue per marijuana-using resident ($171) from states that had operational recreational marijuana markets for a full year in 2022—Alaska, Arizona, California, Colorado, Illinois, Maine, Massachusetts, Michigan, Montana, Nevada, Oregon, and Washington.

Cannabis Collections Provide Windfall Revenues to States

2022 State Marijuana Tax Collections and Estimated Potential Revenue

| State | 2022 Total Cannabis Tax Collections | Estimated Revenue Potential | Cannabis Revenue as a Percentage of Total Revenue Collected Q1 2023 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alabama | - | 86,622,418 | 0.0% |

| Alaska | 29,949,000 | 25,115,376 | 1.3% |

| Arizona | 151,427,000 | 218,350,000 | 0.9% |

| Arkansas | 15,757,000 | 63,215,571 | 0.1% |

| California | 712,405,000 | 1,122,332,666 | 0.2% |

| Colorado | 313,242,000 | 194,430,594 | 1.6% |

| Connecticut | - | 100,974,061 | 0.0% |

| Delaware | - | 26,482,199 | 0.0% |

| Florida | - | 454,981,259 | 0.0% |

| Georgia | - | 250,470,344 | 0.0% |

| Hawaii | - | 28,361,581 | 0.0% |

| Idaho | - | 38,783,607 | 0.0% |

| Illinois | 284,731,000 | 363,233,254 | 0.5% |

| Indiana | - | 172,219,718 | 0.0% |

| Iowa | - | 83,888,771 | 0.0% |

| Kansas | - | 74,833,568 | 0.0% |

| Kentucky | - | 92,260,563 | 0.0% |

| Louisiana | 616,000 | 116,350,821 | 0.0% |

| Maine | 27,350,000 | 49,034,781 | 0.4% |

| Maryland | - | 160,260,015 | 0.0% |

| Massachusetts | 248,436,000 | 255,254,225 | 0.6% |

| Michigan | 190,606,000 | 343,756,024 | 0.7% |

| Minnesota | - | 143,003,873 | 0.0% |

| Mississippi | - | 60,481,925 | 0.0% |

| Missouri | 14,787,000 | 155,988,693 | 0.2% |

| Montana | 35,781,000 | 32,803,756 | 1.1% |

| Nebraska | - | 37,245,931 | 0.0% |

| Nevada | 117,908,000 | 105,928,795 | 1.2% |

| New Hampshire | - | 36,733,372 | 0.0% |

| New Jersey | 23,853,000 | 209,636,502 | 0.1% |

| New Mexico | 21,814,000 | 64,753,247 | 0.3% |

| New York | 11,774,000 | 581,924,960 | 0.0% |

| North Carolina | - | 197,164,241 | 0.0% |

| North Dakota | - | 16,743,584 | 0.0% |

| Ohio | - | 315,907,003 | 0.0% |

| Oklahoma | 54,696,000 | 128,481,377 | 0.4% |

| Oregon | 174,071,000 | 170,852,895 | 0.9% |

| Pennsylvania | 34,061,000 | 315,223,591 | 0.1% |

| Rhode Island | 2,000 | 37,245,931 | 0.1% |

| South Carolina | - | 110,883,529 | 0.0% |

| South Dakota | - | 16,060,172 | 0.0% |

| Tennessee | - | 155,646,987 | 0.0% |

| Texas | - | 492,056,337 | 0.0% |

| Utah | - | 58,260,837 | 0.0% |

| Vermont | 862,000 | 28,703,286 | 0.3% |

| Virginia | - | 211,857,590 | 0.0% |

| Washington | 484,009,000 | 272,510,367 | 1.2% |

| West Virginia | - | 41,175,548 | 0.0% |

| Wisconsin | - | 133,094,405 | 0.0% |

| Wyoming | - | 13,668,232 | 0.0% |

| Total | 2,948,137,000 | 8,465,248,379 |

Sources: U.S. Census Bureau, “Quarterly Summary of State and Local Government Tax Revenue,” and “State Government Administrative Data Publications”; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, “2021 National Surveys on Drug Use and Health”; Author calculations.

In 2022, states collected nearly $3 billion in (medical plus recreational) marijuana tax revenues. The largest and longest-established markets generated the most revenue in California, Washington, and Colorado. In the first quarter of 2023, 10 states—Arizona, Colorado, Maine, Massachusetts, Michigan, Montana, Nevada, New Mexico, Oregon, and Washington—generated more revenue from cannabis than from either alcohol (9 states) or tobacco (Washington).

Marijuana revenues generated more than one percent of total revenues in five states—Alaska, Colorado, Montana, Nevada, and Washington—in the first quarter of 2023, with marijuana revenues comprising nearly 2 percent of all revenue collected in Colorado.

3. Tax design consistency across jurisdictions is important.

While state cannabis operations remain siloed, differences in tax policy across states are inconsequential. However, once interstate commerce is permissible, opportunities for tax arbitrage will be substantial if current state tax designs are not reformed. Tobacco markets illustrate the large opportunities for tax arbitrage when the only difference in tax design is the tax rate, and cannabis tax designs have substantially greater differences than only tax rates.[12]

Producers in states that tax only raw product, for example, could potentially face double taxationDouble taxation is when taxes are paid twice on the same dollar of income, regardless of whether that’s corporate or individual income. of their products if exported into states that tax only final retail sales. On the other hand, product exported in states with only retail taxes into states with only raw material taxes may go untaxed altogether.

Any federal taxes would pyramid on top of state taxes, compounding the effects of taxation. Further, for states that elect to use a different method of taxing cannabis than that which the federal government ultimately uses (e.g., if the federal government applies an ad valorem tax, but the state applies an ad quantum tax), compliance costs will increase substantially.

These issues should not serve as a deterrent to federal legalization or the introduction of interstate commerce. Rather, states should prepare to adjust their tax designs as needed.

Best Practices for Cannabis Taxation

Taxing marijuana is complex, in part because an array of marijuana consumption products exists. Marijuana can be smoked, with different strands having different potency levels of THC, or liquid cannabis extracts and concentrates can be used in the creation of edible or drinkable products, with varying levels of THC.

The solution to marijuana taxation is to tax by potency where possible, and weight where THC content is impractical to measure. The weight-based approach would capture harm derived from the use of smokable products. Eventually, when product testing for THC content in plant materials becomes less costly, products taxed by weight can transition into being taxed by potency. In the short term, a weight-based approach captures externalities better than an ad valorem system and is simple enough to allow new products to enter the market without prohibitively high barriers to product testing simply for tax purposes.

A hybrid weight-potency tax could permit higher tax rates for more potent products with a limited number of categories. This would allow for higher tax rates on more potent products while limiting the costs of testing. A base tax rate could be set by weight for cannabis products containing less than 10 percent THC; that rate could double for products with 10 percent to 25 percent THC and then double again for products containing 25 percent THC or more.

Taxes by potency grow as THC content increases in the product, making more concentrated products more expensive and yielding more revenue, reflecting higher societal costs associated with more potent products. A specific, separate category should be created for edibles and concentrates as they are easier to test. Neither weight nor potency are perfect, but both are substantially better proxies than price-based taxes.

Additionally, cannabis taxes should be levied early in the value chain, similar to alcohol and tobacco excise taxes, to limit the number of taxpayers. Excise tax revenue should be appropriated to relevant spending priorities related to the external harms created by marijuana consumption, such as public safety, youth drug use education, and cessation programs.

Legal markets for cannabis products are still in their infancy, as are the tax policies applied to those markets. A simple, low-rate, and low-cost tax system has the potential to raise significant amounts of revenue, while simultaneously decreasing social harms from cannabis by bringing illicit market transactions into a legal market framework.

[1] Adam Hoffer, “Global Excise Tax Applications and Trends,” Tax Foundation, Apr. 7, 2023, https://taxfoundation.org/research/all/global/global-excise-tax-policy-application-trends/.

[2] David G. Kraenzel, Tim Petry, Bill Nelson, Marshall J. Anderson, Dustin Mathern, and Robert Todd, Industrial Hemp as an Alternative Crop in North Dakota, North Dakota State University, Jul. 23, 1998, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/23514402_Industrial_Hemp_As_An_Alternative_Crop_In_North_Dakota.

[3] N. NicDaéid and K.A. Savage, “Classification,” in Encyclopedia of Forensic Sciences (Second Edition), ed. Jay A. Siegel, Pekka J. Saukko, Max M. Houck (Academic Press, 2013), 29-35.

[4] Anisha R. Turner, Benjamin C. Spurling, and Suneil Agrawal, “Marijuana Toxicity,” in StatPearls (2023), https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430823/.

[5] Pat Oglesby, “Colorado’s Crazy Marijuana Wholesale Tax Base,” Center for New Revenue, Mar. 27, 2014, https://ssrn.com/abstract=2351399.

[6] Adam Hoffer, “Global Excise Tax Applications and Trends,” Tax Foundation, Apr. 7, 2023, https://taxfoundation.org/research/all/eu/global-excise-tax-policy-application-trends/.

[7] Todd Nesbit, “Excise Taxation and Product Quality Substitution,” in For Your Own Good: Taxes, Paternalism, and Fiscal Discrimination in the Twenty-First Century (Arlington: Mercatus Center at George Mason University, 2018).

[8] “May Revision, 2022-23,” State of California, May 13, 2022, https://ebudget.ca.gov/2022-23/pdf/Revised/BudgetSummary/FullBudgetSummary.pdf.

[9] Pablo Valdes-Donoso, Daniel A. Sumner, and Robin Goldstein, “Costs of cannabis testing compliance: Assessing mandatory testing in the California cannabis market,” PloS one 15: 4 (2020), https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7179872/.

[10] This short video summarizes some of the basic issues around cannabis taxation in the United States: https://taxfoundation.org/cannabis/.

[11] Jason Childs and Jason Stevens, “The state must compete: Optimal pricing of legal cannabis,” Canadian Public Administration 62:4 (2019): 656-673.

[12] Adam Hoffer, “Cigarette Taxes and Cigarette Smuggling by State, 2020,” Tax Foundation, December 2022, https://taxfoundation.org/data/all/state/cigarette-taxes-cigarette-smuggling-2022/.

Share this article