Key Findings

- The EU budget agreement reached in 2020 called for a new digital levy as a funding mechanism.

- Evidence on the taxes paid by digital companies calls into question the arguments in favor of a digital levy.

- EU policymakers should focus on continued implementation of digital VAT policies and ongoing international negotiations rather than design a new taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. on digital companies.

- The three digital levy options each have serious flaws and would negatively impact consumers and businesses who are increasingly relying on digital products and services.

Introduction

The budget agreement reached by the European Commission in 2020 described a new digital levy which would be an own resource used to fund the European Union budget.[1] The agreement set a target date of June 2021 for a proposal with an expected implementation at the beginning of 2023.

Recently, the European Commission opened a public consultation on the digital levy under its agenda for a fair and competitive digital economy.[2] The consultation mentions three policy options but no details on how they would be implemented. These options include:

- A corporate income taxA corporate income tax (CIT) is levied by federal and state governments on business profits. Many companies are not subject to the CIT because they are taxed as pass-through businesses, with income reportable under the individual income tax. top-up on all companies with digital activities in the European Union (EU).

- A tax on revenues from certain digital activities in the EU.

- A tax on business-to-business digital transactions in the EU.

Behind these options is an assumption that digital companies should be taxed differently from other firms. This is driven by a misunderstanding about the root causes of the tax rates that digital firms pay and a political effort to design new tax measures rather than attempt fundamental tax reforms in view of the digitalization of the economy.

This discussion is similar to the debate over the EU proposal for a digital services tax from 2018. This paper provides contextual points from that prior debate that are relevant again because of the discussion of a digital levy.

How Much Do Digital Businesses Pay in Taxes?

In the context of the 2018 debate on the EU digital services tax, the European Commission advanced misleading figures about the level of corporate taxes paid by digital companies.[3] Contrary to the Commission’s assertion at the time that digital companies are generally undertaxed, economist Matthias Bauer at the European Center for International Political Economy (ECIPE) showed that digital companies have roughly similar tax burdens as other industries.

| 5-Year Averages | 3-Year Averages | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average Profit Margin | Average ECTR | Average Profit Margin | Average ECTR | |

| Traditional Corporations (EuroStoxx50) | 10.60% | 27.10% | 11.40% | 26.70% |

| Digital Group Corporations | 17.40% | 26.80% | 17.20% | 28.10% |

| MSCI Digital Services Corporations | 15.20% | 29.40% | 15.10% | 32.00% |

| Digital Corporations (The Digital Group and MSCI Digital Services Corporations) | 15.50% | 29.10% | 15.40% | 31.50% |

|

Note: MSCI is Morgan Stanley Capital International. The metrics cover companies like Amazon, Microsoft, Oracle, and other large digital services firms. See the source for full lists of companies included in the groupings. Source: Matthias Bauer, “Digital Companies and Their Fare Share of Taxes: Myths and Misconceptions,” ECIPE, February 2018, https://ecipe.org/publications/digital-companies-and-their-fair-share-of-taxes/?chapter=all. |

||||

This is not to say that digital companies are not granted tax preferences. In fact, many European domestic policies are designed to grant high-tech business models with tax relief for research and development (R&D) expenditures and profits from their intellectual property. Income from patents is taxed as low as 4.5 percent in Hungary.[4] Even France, which has a relatively high corporate tax rate of 32 percent, levies just a 10 percent corporate tax rate on patent income.

Recently, governments have tightened the eligibility rules for patent boxes. A company cannot simply place a patent in a French subsidiary to receive the 10 percent reduced rate. The rules require companies to perform other activities like R&D in the same jurisdiction to benefit from the patent boxA patent box—also referred to as intellectual property (IP) regime—taxes business income earned from IP at a rate below the statutory corporate income tax rate, aiming to encourage local research and development. Many patent boxes around the world have undergone substantial reforms due to profit shifting concerns. rate.[5] This means that companies that do their R&D outside of Europe would not tend to benefit from the reduced patent box rates within Europe.

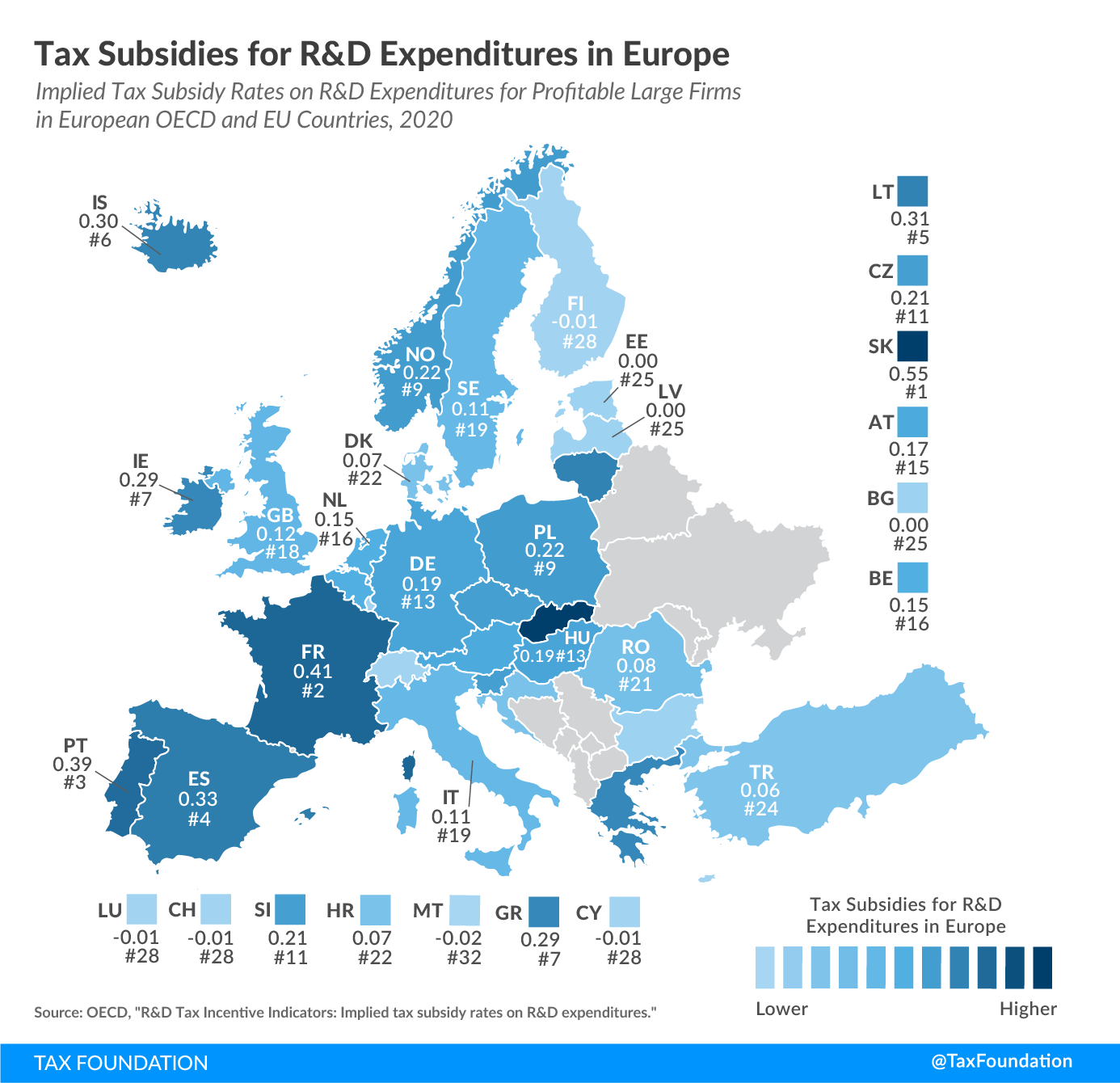

Tax preferences for R&D expenditures are also prevalent throughout Europe with EU member states Slovakia and France providing the largest tax subsidies to R&D spending. To the extent that the digital economy is undertaxed in Europe, it is likely significantly due to these generous tax incentives.

Patent boxes and R&D subsidies are not only available to digital firms, though. Any business that relies heavily on research and development or intangible assets like patents could stand to benefit from the tax relief these policies offer, as long as it meets the eligibility requirements.

Because the United States is home to some large tech companies, it is worth mentioning how U.S. multinationals are taxed. Prior to the 2017 tax reform, there was a concern that the U.S. tax system created under-taxed income by allowing companies to defer their U.S. tax burden on foreign income indefinitely. U.S. companies could earn profits in low- or zero-tax jurisdictions or otherwise arrange their affairs so that they faced taxation neither in the U.S. nor a foreign country. This “stateless income” was a direct result of the U.S. worldwide tax systemA worldwide tax system for corporations, as opposed to a territorial tax system, includes foreign-earned income in the domestic tax base. As part of the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), the United States shifted from worldwide taxation towards territorial taxation. .[6]

The 2017 tax reform changed that, however, as the U.S. moved to a partial territorial tax systemTerritorial taxation is a system that excludes foreign earnings from a country’s domestic tax base. This is common throughout the world and is the opposite of worldwide taxation, where foreign earnings are included in the domestic tax base. and implemented a type of global minimum tax. Profits that had previously been untaxed by the U.S. have now faced both a one-time transition tax on accrued foreign earnings (deemed repatriationRepatriation is the process by which multinational companies bring overseas earnings back to the home country. Prior to the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), the US tax code created major disincentives for US companies to repatriate their earnings. Changes from the TCJA eliminate these disincentives. tax) and the annual tax on Global Intangible Low Tax Income (GILTI). For those U.S. companies whose foreign earnings went untaxed or under-taxed under the previous system, they are now facing new tax policies designed specifically to target that foreign income.[7]

How Is the Digital Economy Taxed?

The digital economy can be taxed in more ways than one, but only in some areas are specific measures necessary to ensure digital companies are taxed at similar levels as non-digital businesses. In general, tax policies should not be tailored to specific industries. The corporate tax system is designed to tax profitable companies where they earn their profits. As mentioned previously, digital companies already face comparable levels of tax under corporate taxes.

Separately, consumption taxA consumption tax is typically levied on the purchase of goods or services and is paid directly or indirectly by the consumer in the form of retail sales taxes, excise taxes, tariffs, value-added taxes (VAT), or an income tax where all savings is tax-deductible. systems are meant to tax consumption at the place of the buyer. Many countries have been adapting their consumption tax policies to ensure that e-commerce is included in the tax base for value-added taxes (VATs) and similar policies. This is a move to make VAT more efficient and will serve to boost revenues as e-commerce continues to grow.

The EU has already adopted significant measures designed to tax the digital economy through the VAT system. In February 2020, the OECD Secretary-General reported that measures connected to the taxation of the digital economy in the EU had contributed additional revenues summing €3 billion in 2015 and €4.5 billion in 2018.[8] The EU VAT directive on e-commerce is estimated to bring in an additional €7 billion each year once it is implemented.[9] These new rules are currently expected to come into force on July 1, 2021.

Problems with Special Taxes on the Digital Economy

The current digital levy consultation outlines options for special taxes on digital companies. There are three key problems with this approach.

First, defining the targeted industry is a fraught exercise. The digitalization of the economy is widespread, and rules designed to tax a narrow set of companies will introduce new distortions and complexities into an already complex tax system. Taxes aimed at digital companies quickly begin to look like excise taxes, which are usually designed to stunt the growth of consumption of targeted goods and services.

This is not to say that the underlying tax system is without flaw. There have been and continue to be many challenges of taxing corporate profits in the context of globalization. While digitalized business models may exacerbate these underlying issues, reforms targeted at digital companies will leave the overall tax system less stable and more complex than fundamental reforms.[10]

Second, the taxes themselves are very likely to lead to unintended consequences. The Digital Services Taxes (DSTs) that have been adopted in many EU countries have caused some companies hit by them to increase the fees paid by their European customers.[11] While the proposals are to tax digital companies, the pass-through of the tax burden to brick-and-mortar firms seeking to reach customers through the internet cannot be ignored. A small store or vacation property may rely significantly on online customers for their business. A tax that increases the cost of reaching customers through an online marketplace is not only a digital tax, but also a tax on businesses that are seeking to sell both domestically and globally.

A third problem with the EU’s approach is the context in which the digital levy is being discussed. Ongoing negotiations at the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) are intended to eliminate unilateral taxes on digital companies in favor of a new international agreement.[12] Several EU countries have adopted a DST, and it seems contradictory that policymakers would take steps to implement a new unilateral measure at the EU level. Unlike the DSTs, which are often meant to be temporary measures, it appears that the digital levy might be intended as a permanent policy given that it is part of the financing package for the EU budget.

The Digital Levy Options

The three options that are mentioned in the digital levy consultation would all create economic harm and additional complexities. The main challenge for each option will be defining what the “digital” tax baseThe tax base is the total amount of income, property, assets, consumption, transactions, or other economic activity subject to taxation by a tax authority. A narrow tax base is non-neutral and inefficient. A broad tax base reduces tax administration costs and allows more revenue to be raised at lower rates. is. Drawing lines around the digital economy is not a valuable exercise except perhaps for political purposes. However, tax policy should be based on principles instead of political choices about which industries should face customized rules or not.

A top-up tax on corporate income aimed at digital companies would have to comport with the variety of corporate tax rates across Europe and the different definitions of corporate income and relevant deductions. A 2 percent top-up tax in a country with generous provisions for loss deductions or capital investments would have different effects than a similar top-up in a country with a broader corporate income tax base.

A tax on revenues would, as the DSTs have done, continue the return of turnover taxes back to Europe. Unlike taxes on profits, taxes on revenues are regressive, taxing firms that are less profitable at higher effective rates than more profitable companies. The low statutory tax rates disguise the harm that this inefficient approach to taxation can bring.

A tax on digital business-to-business (B2B) transactions would also create economic harm. Generally, tax systems are designed to avoid taxing business inputs by allowing deductions for labor costs, inventory, and other inputs. Digital products sold in the B2B context are also business inputs. A company that pays for services to support its website should be able to deduct those costs for corporate income tax purposes and get a credit for any VAT paid on those services. EU policymakers should avoid significantly raising costs on digitalization and not levy a special tax on digital B2B transactions.

As mentioned, the digital levy does not exist in a vacuum. Several EU countries already have DSTs, and the OECD is working toward international solutions to tax the digital economy.[13] Rather than contributing to the long-term stability of the corporate tax system and avoiding international tax and trade disputes, the digital levy effort seems designed to create unnecessary conflicts and complexities for digital companies in the EU.

A Digital Future for Europe

The EU’s agenda on digitalization is unfortunately focused on creating new tax challenges rather than on fundamental issues stemming from technological progress. EU member states face many challenges to improve access to digital products and services. The European Commission should not stand in the way of those efforts by developing harmful new taxes.

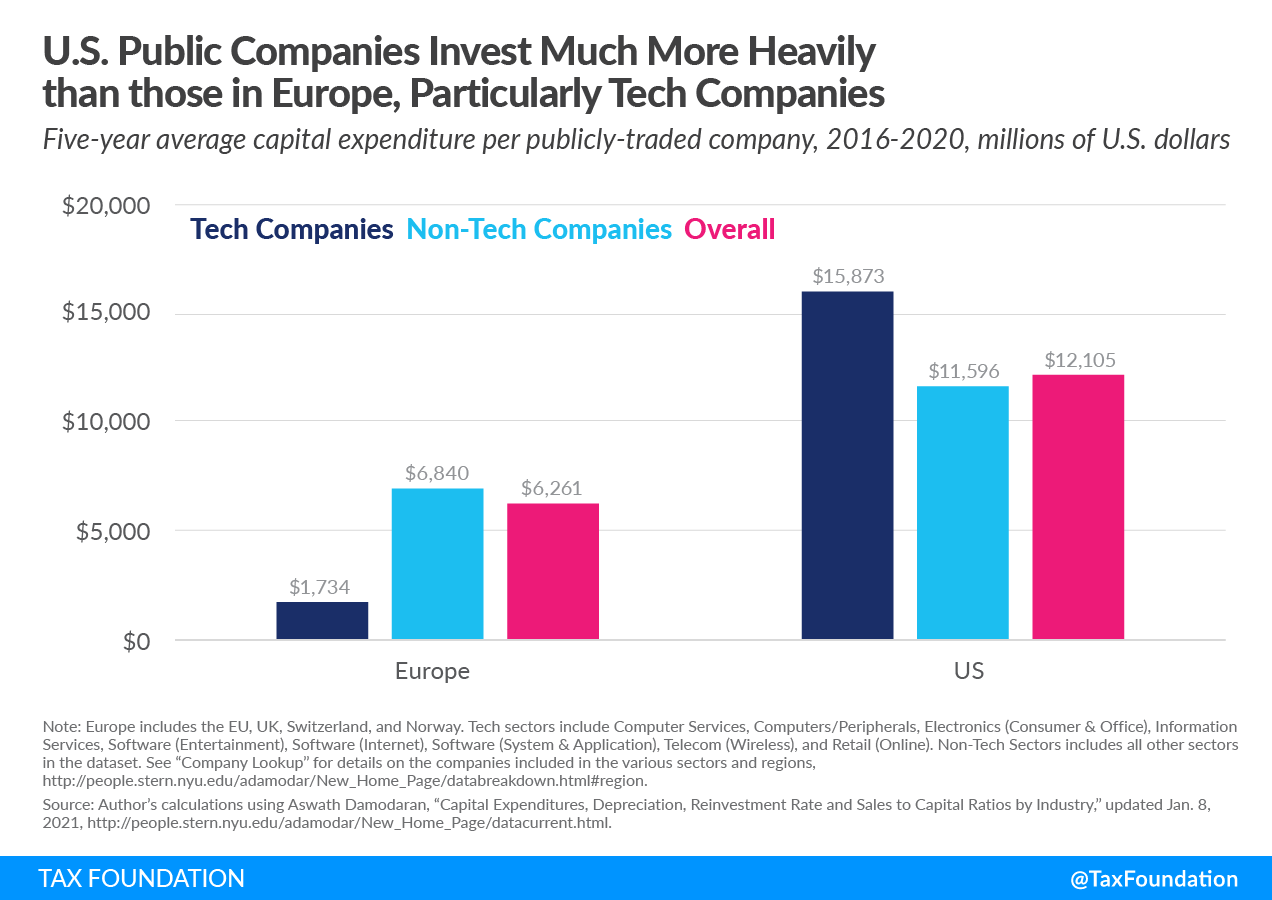

Publicly traded tech companies in Europe fall behind those in the U.S. when it comes to capital expenditure. Digital infrastructure is necessary to maintain stable web-based services. Higher tax burdens on digital companies could exacerbate the challenges that tech firms face in building out their infrastructure in Europe.

The European Commission should abandon its approach on a digital levy and instead focus on reaching an international agreement on rules addressing the tax challenges of the digital economy. Rather than spending time developing new taxes, EU policymakers should work to improve existing taxes and ensure that tax policy does not stand in the way of growth as Europe looks toward an economic recovery in the near future.

Conclusion

The consultation on the EU’s digital levy provides an opportunity for policymakers and taxpayers to reflect on the underlying issues of digital taxation and potential consequences from a digital levy. The three options described in the consultation document raise many concerning issues including overburdening business-to-business e-commerce and compatibility with existing corporate tax rules. Many countries around the world are focused on resolving issues of digital taxation through an agreement at the OECD. Unless the EU digital levy is designed with an OECD agreement in mind, it is likely to cause more uncertainty in cross-border tax policy. The EU should focus on policies that advance the digitalization of the economy rather than unilateral approaches to taxing the digital economy.

[1] European Commission, “EU budget: European Commission welcomes agreement on €1.8 trillion package to help build greener, more digital and more resilient Europe,” Nov. 10, 2020, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_20_2073.

[2] European Commission, “A Fair & Competitive Digital Economy – Digital Levy,” https://ec.europa.eu/info/law/better-regulation/have-your-say/initiatives/12836-Digital-Levy.

[3] The European Commission misinterpreted a study of forward-looking effective tax rates based on the most favorable tax treatment of investments by digital companies in Europe as evidence that the overall tax burden on digital businesses is low. Matthias Bauer, “Digital Companies and Their Fair Share of Taxes: Myths and Misconceptions,” ECIPE, February 2018, https://ecipe.org/publications/digital-companies-and-their-fair-share-of-taxes/?chapter=all; and Jack Schickler, “EU Study’s Author Doubts Digital Transactions Undertaxed,” Law360.com, Mar. 6, 2018, https://www.law360.com/articles/1019073/eu-study-s-author-doubts-digital-transactions-undertaxed.

[4] Elke Asen and Daniel Bunn, “Patent Box Regimes in Europe,” Tax Foundation, Nov. 26, 2020, https://taxfoundation.org/patent-box-regimes-in-europe-2020/.

[5] Elke Asen, “How Patent Boxes Impact Business Decisions,” Tax Foundation, June 20, 2019, https://taxfoundation.org/how-patent-boxes-impact-business-decisions/.

[6] Edward D. Kleinbard, “Stateless Income,” Florida Tax Review 11:9 (November 2011), https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1791769.

[7] Gary D. Sprague, “A Critical Look at the European Commission Staff Impact Assessment Relating to the Proposed EU Directives on Taxation of the Digital Economy,” Bloomberg BNA, July 13, 2018.

[8] OECD, “OECD Secretary-General Tax Report to G20 Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors,” February 2020, http://www.oecd.org/ctp/oecd-secretary-general-tax-report-g20-finance-ministers-riyadh-saudi-arabia-february-2020.pdf#page=14.

[9] This is a 5 percent increase over the baseline scenario in the impact assessment. See European Commission, “Modernising VAT for cross-border e-commerce,” https://ec.europa.eu/taxation_customs/business/vat/modernising-vat-cross-border-ecommerce_en.

[10] Michael P. Devereux and John Vella, “Response to the EU Commission’s consultation: Fair taxation of the digital economy,” Oxford University Centre for Business Taxation, Jan. 3, 2018, https://circabc.europa.eu/webdav/CircaBC/Taxation%20%26%20Customs%20Union/Results%20of%20the%20open%20public%20consultation/Library/Results%20of%20the%20open%20public%20consultation/Individuals/bc31d10a-b132-41a7-8be1-6f5744bcb9ed_Response_to_EU_Consultation_on_DE_Devereux_Vella_Final.docx.

[11] Some examples of this include “Amazon to Hike Fees for Spanish Users After New Digital Tax,” Reuters, Jan. 22, 2021, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-amazon-spain-tax/amazon-to-hike-fees-for-spanish-users-after-new-digital-tax-idUSKBN29R13B; Alex Barker, “Google to Pass on Cost of Digital Services Taxes to Advertisers,” The Irish Times, Sept. 1, 2020, https://www.irishtimes.com/business/economy/google-to-pass-on-cost-of-digital-services-taxes-to-advertisers-1.4344151; and Silvia Amaro, “Big Tech Finds a Way to Pass on the Cost of Digital Taxes in Europe,” CNBC, Sept. 3, 2020, https://www.cnbc.com/2020/09/03/big-tech-finds-a-way-to-pass-on-the-cost-of-digital-taxes-in-europe.html.

[12] OECD, “Tax Challenges Arising from Digitalisation – Report on Pillar One Blueprint,” Inclusive Framework on BEPS, Oct. 14, 2020, https://www.oecd.org/tax/beps/tax-challenges-arising-from-digitalisation-report-on-pillar-one-blueprint-beba0634-en.htm.

[13] Ibid.

Share this article