The U.S. Supreme Court adjourns for the summer soon, which means decisions in all pending cases are due to come down by the end of June. One of these is the South Dakota v. WayfairSouth Dakota v. Wayfair was a 2018 U.S. Supreme Court decision eliminating the requirement that a seller have physical presence in the taxing state to be able to collect and remit sales taxes to that state. It expanded states’ abilities to collect sales taxes from e-commerce and other remote transactions. case, challenging South Dakota’s application of its sales tax to internet retailers who sell into South Dakota but have no property or employees in the state.

At issue is the case Quill Corp. v. North Dakota from 1992, which set the property or employees standard for sales taxes using the Court’s (debated) dormant commerce clause power to restrict state taxation of interstate commerce. Lots of ink has been spilled on the Wayfair case, with 15 briefs filed in support of South Dakota, 22 filed in support of Wayfair, and two in support of neither (including the Tax Foundation’s: we think the South Dakota law is constitutional but other versions wouldn’t be, and want the Court to state a clear rule applicable to all taxes, not just sales taxes).

The case was argued on April 17. While many commentators going into it expected an easy path for South Dakota, justices expected to side with the state stayed mostly silent, ceding time to justices skeptical of South Dakota’s law (Justice Sonia Sotomayor began the argument with about five rapid-fire questions in a row), and several justices expressed frustration with disputed facts (such as whether South Dakota’s system is really complex or really easy) and whether Quill should be better overturned by the Court or by Congress. (Because of a constitutional wrinkle, Congress has the power to legislatively overturn the Quill decision but has not done so.) There was also recognition that the issue will not go away: finding in favor of South Dakota’s mild version may lead to more aggressive and damaging versions of the law; finding in favor of Wayfair may result in states instead passing a mandated mail-notice-to-all-your-customers regime as has been adopted in Colorado.

Supreme Court predicting is an exercise in futility, because justices use questions not just to say what’s on their mind but also to play devil’s advocate, nudge their colleagues, or explore ramifications of potential decisions. But let’s do it anyway.

- If South Dakota prevails, their majority would be Justice Anthony Kennedy (who wrote in a previous opinion, in DMA, that he thinks Quill is now the wrong rule), Justice Clarence Thomas (who has for years consistently refused to exercise the Court’s dormant commerce clause power as he considers it illegitimate), Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg (who has generally upheld state taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. laws and lobbed softballs at the state at oral argument), and Justice Neil Gorsuch (who wrote as a lower court judge that Quill should have an expiration date). That’s four, so they’d need to pick up one other justice among Chief Justice John Roberts (who noted in oral argument only that Congress is probably best equipped to draw lines), Justice Stephen Breyer (who said in oral argument that he sees the merit on both sides), or Justice Elena Kagan (who asked tough questions of both sides).

- If Wayfair prevails, their majority would be at least Justice Sotomayor (who at oral argument listed a number of problems she identified with the South Dakota law) and Justice Samuel Alito (a champion of the commerce clause, although that is not the same thing as physical presence). Those two would have to be joined by Roberts, Breyer, and Kagan.

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

SubscribeJust knowing who prevails won’t be enough information as the variety of outcomes is quite a spectrum. I see five potential outcomes:

- Quill Redux: The Court does exactly what it did in Quill: reaffirm the physical presence rule, perhaps with some misgivings over whether it is the correct rule but expressly leaving it to Congress to change. The reason would be that Congress is best equipped to decide the trade-offs and tamper with people’s reliance on the current long-standing rule. The debate in Congress would continue, and states may instead pursue the intrusive Colorado notice-and-reporting law that has been implicitly found to be constitutional.

- See You Again Soon: The Court upholds the South Dakota law but gives little to no guidance on whether a more aggressive law would be constitutional. States will inevitably pass harsher versions of the law, so the courts would soon be confronted with those cases, necessitating guidance on where the line is.

- Isn’t This Legislating: Uphold South Dakota and give clear guidance on what is permissible and what is not. This puts the Court out of its comfort zone, since it requires drawing a line between types of state laws that are constitutional and types that are not. Adhering to common definitions, requiring uniformity between state sales taxes and local sales taxes, banning retroactive collection, and excluding small sellers from having to comply may all be good ideas, but are they truly constitutionally mandated? But if this is the route the Court takes, states will try to match their laws to the new standard.

- Sky Fall: Reverse Quill completely and permit states to do anything, limited only by future congressional action. The Court could state that its clear physical presence isn’t a functioning limitation anymore, acknowledge that Congress should fix it, and prompt it by stepping away and letting state laws stand. Expect stampedes and panics as some states pass crazy laws (such as “cookie laws” that impose tax obligations on any company anywhere in the world with a website that puts cookies on computers in the state), chaos for retailers as they comply with a bunch of different standards, and Congress stirring out of complacency to address the crisis. The Court actually did this in Northwestern Cement Co. v. Minnesota (1959), briefly upholding state taxes on businesses with door-to-door salespeople before Congress quickly intervened.

- Just Kidding: Remand the case to the lower court to create a better record, or dismiss it as improvidently granted. The Court could become so frustrated with it that it decides to punt, perhaps so a lower court can find some answers to how complex the South Dakota law really is. If this happens, with Congress not acting and the Court staying out, expect states to pass a variety of tax collection laws.

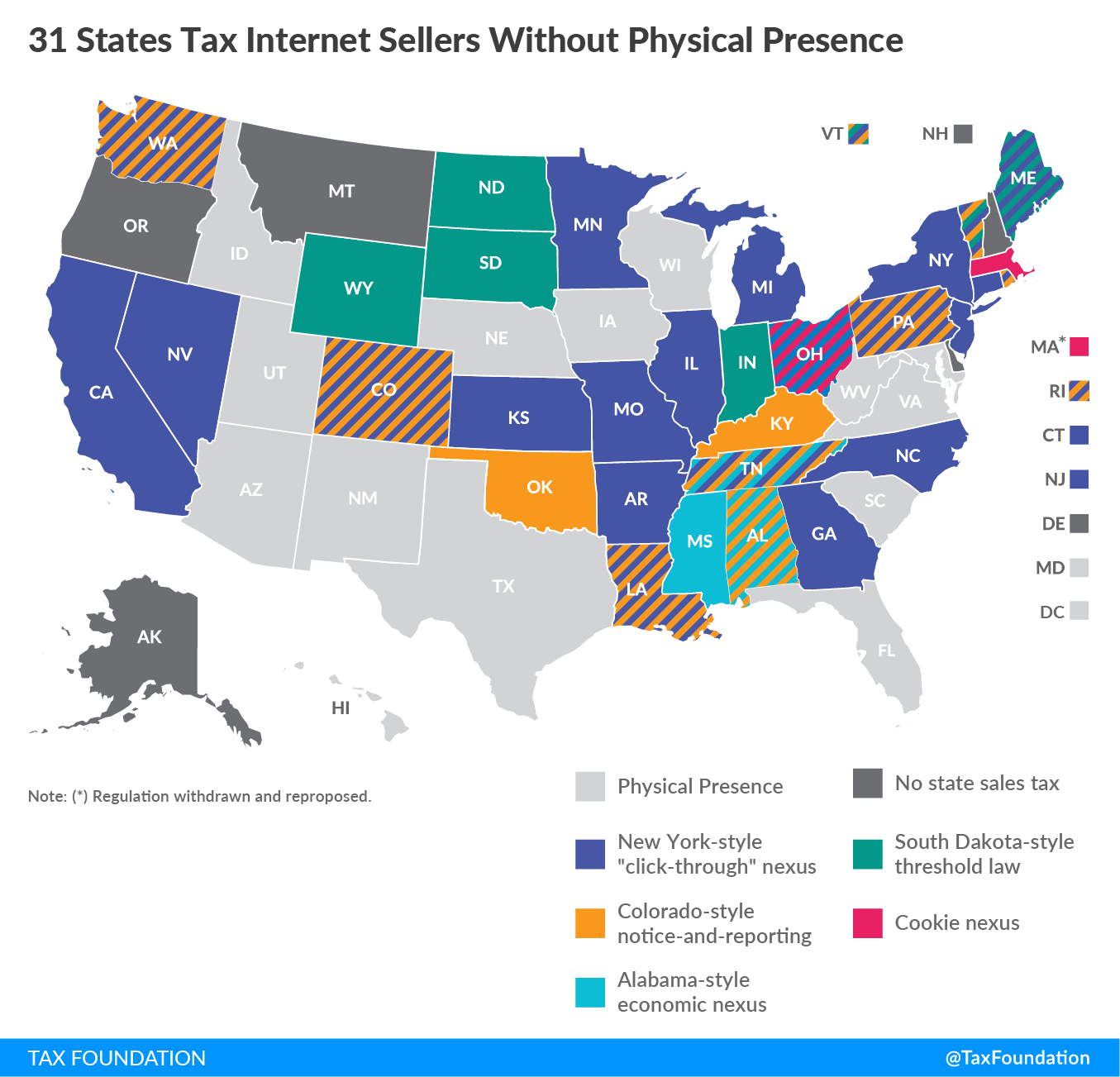

And, a reminder, 31 states currently have laws taxing Internet sales. So even a Wayfair victory in Wayfair doesn’t mean states won’t tax the Internet. It means they’ll do so in less simplified and direct ways than South Dakota has proposed.

When the decision comes down, we will analyze it and its implications!

Share this article