In a recent paper entitled “The Tax Foundation’s score on the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act”, Greg Leiserson from the Washington Center for Equitable Growth expressed concerns about the equations the TaxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. Foundation’s model uses to measure the cost of capital. After being made aware of the inaccuracy, Tax Foundation staff worked with Leiserson to develop a new equation that more accurately measures the cost of capital. Tax Foundation economists then used the updated model to re-score our analysis of the House proposed Tax Cuts and Jobs Act. We also used this updated version of the model to score the Senate’s version of the tax act.

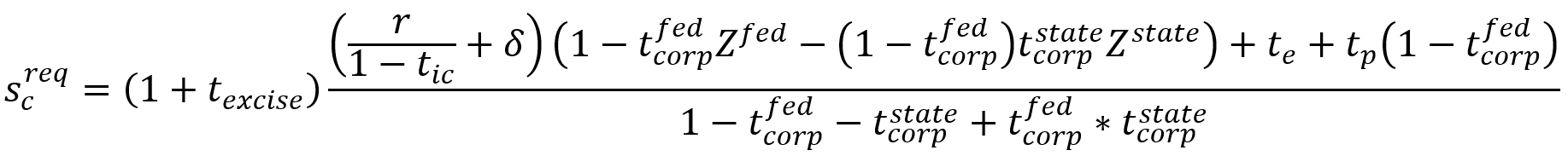

Like all modelers, we are always striving to improve our model and welcome constructive suggestions. Below, we outline the new service price equation that we will include in the next update to our Overview of the Tax Foundation’s Taxes and Growth Model.

Leiserson raised some additional questions about our model, which we take time to answer below. In particular, he questioned our approach to modeling the estate tax. While these are valid points, we think these are issues about which economists can have honest differences of opinion and that our assumptions are reasonable.

Measuring Federal and State Depreciation and the Cost of Capital

Leiserson found that we could improve the portion of the equation that describes the benefits from state deductions from depreciating assets. The old equation had a term that suggests the federal taxes paid could be deducted against the state tax liability. With the help of Leiserson, we identified the portion of the equation and updated the model.

The new cost of capital equation, below, eliminates the interaction between the net present value of the federal depreciationDepreciation is a measurement of the “useful life” of a business asset, such as machinery or a factory, to determine the multiyear period over which the cost of that asset can be deducted from taxable income. Instead of allowing businesses to deduct the cost of investments immediately (i.e., full expensing), depreciation requires deductions to be taken over time, reducing their value and discouraging investment. schedule and the state tax rate. This can be interpreted as state depreciation affecting federal tax liability, while federal depreciation schedules do not affect state burdens.

We scored three policies changes to illustrate the change in the cost of capital: implementing full expensing for all businesses, a move to a 20% corporate rate, and a combination of both. We found that the new equation increased the effects of full expensingFull expensing allows businesses to immediately deduct the full cost of certain investments in new or improved technology, equipment, or buildings. It alleviates a bias in the tax code and incentivizes companies to invest more, which, in the long run, raises worker productivity, boosts wages, and creates more jobs. by about 9%, decreased the effects of a 15 percentage point cut of the corporate rate by 11%, and decreased the combined policy effects by about 2%. As such, our old equation was underestimating the effects of full expensing and overestimating the effects of a corporate rate cut.

| Old Score | New Score | Percent Change | |

|---|---|---|---|

| GDP change | 4.00% | 4.40% | 9% |

| GDP, long-run change in annual level (billions of 2016 $) | $770 | $841 | 9% |

| Private business stocks (equipment, structures, etc.) | 11.30% | 12.40% | 10% |

| Wage rate | 3.40% | 3.70% | 9% |

| Full-time Equivalent Jobs (in thousands) | 761 | 829 | 9% |

|

Weighted Average service price |

|||

| Corporate | -7.10% | -7.80% | 9% |

| Noncorporate | -4.90% | -5.20% | 8% |

| All business | -6.40% | -7.00% | 9% |

| Old Score | New Score | Percent Change | |

|---|---|---|---|

| GDP change | 3.10% | 2.70% | -11% |

| GDP, long-run change in annual level (billions of 2016 $) | $587 | $524 | -11% |

| Private business stocks (equipment, structures, etc.) | 8.50% | 7.60% | -11% |

| Wage rate | 2.60% | 2.30% | -11% |

| Full-time Equivalent Jobs (in thousands) | 592 | 530 | -10% |

|

Weighted Average service price |

|||

| Corporate | -7.40% | -6.60% | -10% |

| Noncorporate | 0.30% | 0.20% | -16% |

| All business | -4.90% | -4.40% | -10% |

GDP change5.60%5.50%-2%

| Old Score | New Score | Percent Change | |

|---|---|---|---|

| GDP, long-run change in annual level (billions of 2016 $) | $1,078 | $1,052 | -2% |

| Private business stocks (equipment, structures, etc.) | 16.00% | 15.60% | -3% |

| Wage rate | 4.80% | 4.60% | -2% |

| Full-time Equivalent Jobs (in thousands) | 1,059 | 1,034 | -2% |

|

Weighted Average service price |

|||

| Corporate | -10.70% | -10.20% | -4% |

| Noncorporate | -4.80% | -5.20% | 9% |

| All business | -8.80% | -8.60% | -2% |

Questions about Measuring the Estate TaxAn estate tax is imposed on the net value of an individual’s taxable estate, after any exclusions or credits, at the time of death. The tax is paid by the estate itself before assets are distributed to heirs.

Leiserson gives three reasons that the TAG model inappropriately models the estate tax’s effect on the cost of capital. We believe these are a matter of academic opinion and address each of his critiques with an explanation of our assumptions.

First, he argues that the marginal investor has no incentive to hold assets at death. Leiserson gives three reasons that the TAG model inappropriately models the estate tax’s effect on the cost of capital. We believe these are a matter of academic opinion and address each of his critiques with an explanation of our assumptions.

Indeed, the underlying assumption of the model appears to be not only that increases in investment financed by increases in saving are uniform (in percentage terms) across the population, but also that they translate into increases in assets held at death, which also need not be true.

Because estate taxes are not paid by the firm, they only affect the discount rate of the individual. Estate taxes change the willingness of an individual to hold wealth since it limits the amount that can be passed down to an individual’s family or a social cause.

The reason is that the value of the future consumption falls by the estate tax rates multiplied by the likelihood of death. In other words, if an individual is unlikely to be alive when the investment matures, then current consumption becomes more attractive than the after-tax consumption bestowed to the next generation.

In addition, when an individual dies, the principal is also reduced because the entire principal is subject to the estate tax. The loss of the principal to the tax further reduces the willingness to invest because an individual could consume the entire principal now rather than pay the tax in the scenario where the individual dies. As such, the death scenario must also scale up the principal by the amount of the estate tax.

For example, if the probability of death is 50% per year and the estate tax is 60%, then the expected required return would be 0.5*r + 0.5*(1+r)/(1-0.6)= 1.75*r + 1.625. Using the current return from the TAG model, the expected required return would be over 162%.

Theoretically, this could be possible, but two aspects of the estate tax limit the impact. First, average individuals in the OECD do not have a 50% chance of dying in the following year of their lives. Most people believe they are very unlikely to die in the next year. Second, due to the large exemption in the estate and inheritance tax, the average rate is relatively small compared to the marginal rate. As such, the impact on the required return is most limited to the effect of losing the principal.

Since the bulk of the tax is on the value of the assets and not the return on the assets, the estate tax is a de facto property tax. Although very few individuals will pay the tax, those who do pay it have a relatively heavy burden. As such, the expected, average tax on property can be estimated and added to the cost of capital formula. This has been done in the TAG model.

Second, Leiserson argues that the marginal investor is likely foreign given the open economy assumption of the TAG model.

Yet assuming that foreign investors are the marginal source of finance can dramatically change the effects of the tax system on the economy. In the extreme case in which capital is perfectly mobile across countries—the assumption made by the Tax Foundation—investor-level taxes in the United States that do not apply to foreign investors become irrelevant to the determination of the capital stock.

We do not believe the marginal investor is foreign. Given risk-adjusted returns, foreign investors are unlikely to be the marginal investor because their risk preferences tend to be more risk-averse than domestic, individual investors. The marginal investment tends to be a high-risk, higher-return asset. At the margin, the risk-adjusted return is acceptable to the risk-preferring domestic investor and unacceptable to the risk-averse foreign investor. This is backed by the fact that a large portion of aggregate foreign investors’ portfolios consist of U.S. treasuries.

We recognize Leiserson’s point that when tax policy changes, the TAG model assumes that foreign financial flows cover the required savings to expand the capital stock. On the surface, this would suggest that the marginal investor is foreign, but this is only true if risk preferences are ignored.

When taxes are reduced, after-tax returns increase while risk remains the same. In this case, risk-averse investors, such as foreign investors, increase their holdings of low-risk assets, such as U.S. Treasuries, to reflect the higher return. This, in turn, puts pressure on more-risk-preferring investors, such as domestic individuals, to find other investment opportunities. Investors with higher risk tolerances are drawn to the higher-risk, higher-return investments, which are at the margin. As such, the United States can have strong financial inflows while the marginal investor remains a domestic investor.

Domar-Musgrave’s theory on risk preferences and taxes hinges on risk-adjusted returns. In fact, they theorize that a reduction in taxes increases risk (assuming full loss deductibility), which would make the risk-preferring investor even more important at the margin during a tax cut.

Third, Leiserson argues it is inappropriate to gross up the estate tax by the corporate tax.

Third, this modeling approach appears to treat the estate tax as a nondeductible tax for the purposes of business income taxes. If the tax is nondeductible, then businesses must not only pay the estate tax but also corporate income tax on the additional return they earn to cover the estate tax.

If the estate tax is a de facto property taxA property tax is primarily levied on immovable property like land and buildings, as well as on tangible personal property that is movable, like vehicles and equipment. Property taxes are the single largest source of state and local revenue in the U.S. and help fund schools, roads, police, and other services. , as we suggest above, and if it is not deductible from income taxes, which the estate tax is not, then it is only appropriate to scale the estate tax by the corporate income taxA corporate income tax (CIT) is levied by federal and state governments on business profits. Many companies are not subject to the CIT because they are taxed as pass-through businesses, with income reportable under the individual income tax. . If there were a property tax on productive capital that was not deductible against the income tax, we would model it exactly as we are modeling the estate tax. As such, we gross up the estate tax by the income tax so that we model property taxes consistently.

The Tax Foundation appreciates Leiserson’s review of the TAG model. We invite more academics to review the TAG model and start a conversation with us to improve and expand the TAG model.

Share this article