Several of Massachusetts’ largest employers have created a coalition to seek a change to Massachusetts’ corporate income apportionmentApportionment is the determination of the percentage of a business’ profits subject to a given jurisdiction’s corporate income or other business taxes. U.S. states apportion business profits based on some combination of the percentage of company property, payroll, and sales located within their borders. formula. The coalition wants Massachusetts to use “single sales factor” apportionment for all industries as an investment incentive to employers who have significant payroll and property located within the Commonwealth.

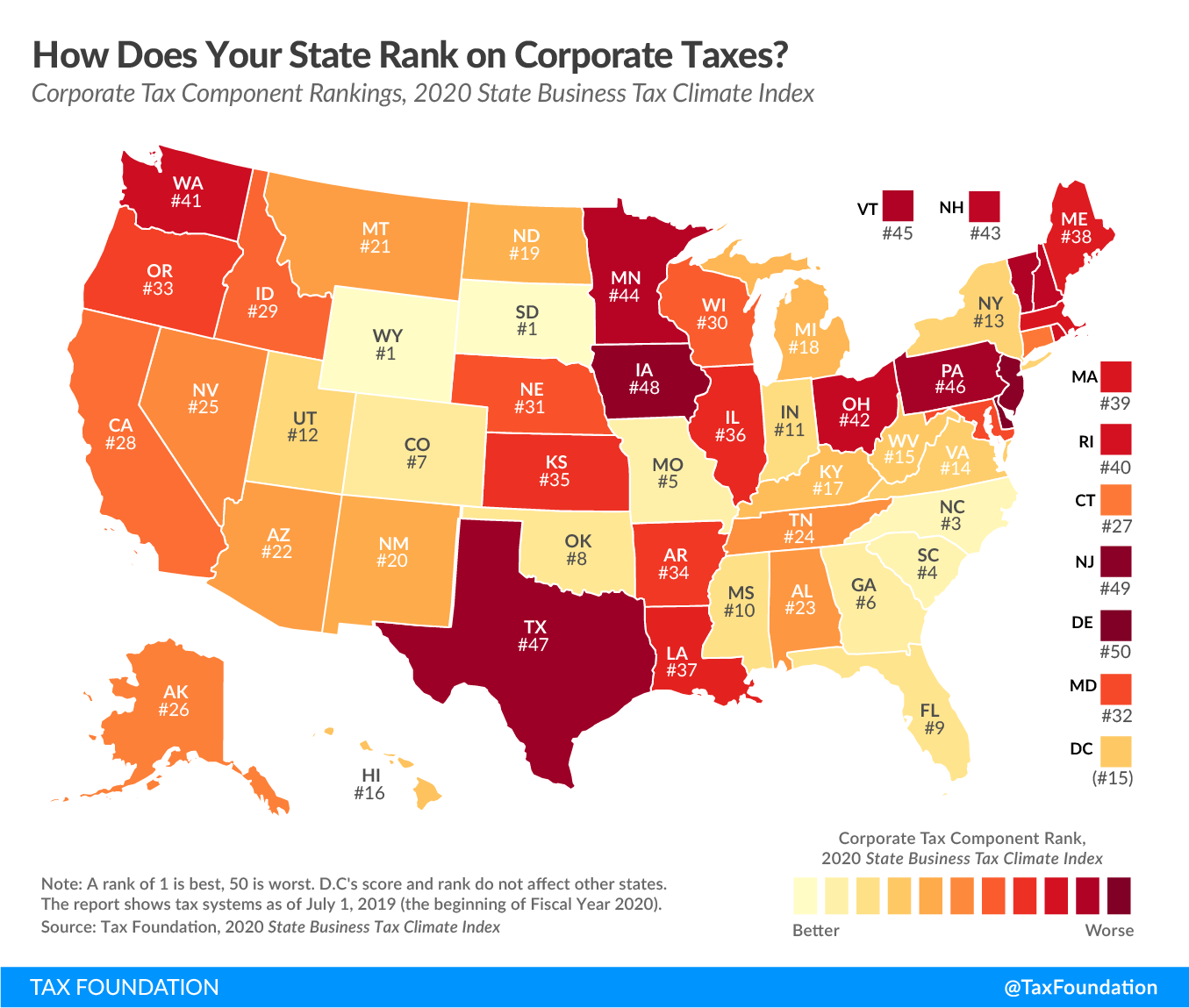

In weighing this apportionment change, Massachusetts lawmakers should consider additional reforms to make its corporate excise taxAn excise tax is a tax imposed on a specific good or activity. Excise taxes are commonly levied on cigarettes, alcoholic beverages, soda, gasoline, insurance premiums, amusement activities, and betting, and typically make up a relatively small and volatile portion of state and local and, to a lesser extent, federal tax collections. code more neutral and competitive. Massachusetts’ corporate excise taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. code contains several outdated provisions, such as a capital stock tax and a corporate income throwback rule, whose effects disincentivize investment and make Massachusetts uncompetitive with other states. Massachusetts ranks 39th among corporate codes in the Tax Foundation’s 2020 State Business Tax Climate Index, trailing neighboring Connecticut (27th) and New York (13th).

Massachusetts’ corporate apportionment formula creates non-neutral treatment among industries. The Commonwealth currently applies single sales factor apportionment to manufacturing companies, defense contractors, and financial service providers. These companies thus are subject to Massachusetts’ 8 percent corporate tax (9 percent for financial services providers) only for the portion of their income generated from in-state sales. In contrast, the rest of Massachusetts businesses are taxed based on a form of three-factor apportionment known as double-weighted sales factor apportionment—where their sales are generated (50 percent), where their payroll is located (25 percent), and where their physical property is located (25 percent).

Tax Foundation does not grade a state’s tax competitiveness based upon its factors of corporate apportionment formula. While credible research points to single sales factor apportionment as an incentive to increase employment in a state, this advantage is weighed against other ways that single sales factor apportionment could affect tax rate competitiveness. However, there is no doubt that the Commonwealth should seek neutrality in its apportionment formula by choosing one formula and applying it neutrally to all industries—whatever that formula is—especially since multiple apportionment formulas are highly complex for Massachusetts businesses that file combined returns (where the corporate parent’s tax return includes affiliated business that can span multiple industries).

There are several other provisions in Massachusetts’ corporate excise tax that are non-neutral, contradictory, and a disincentive to economic growth. Lawmakers would do well to continue their look at a broader cleanup to streamline the corporate code.

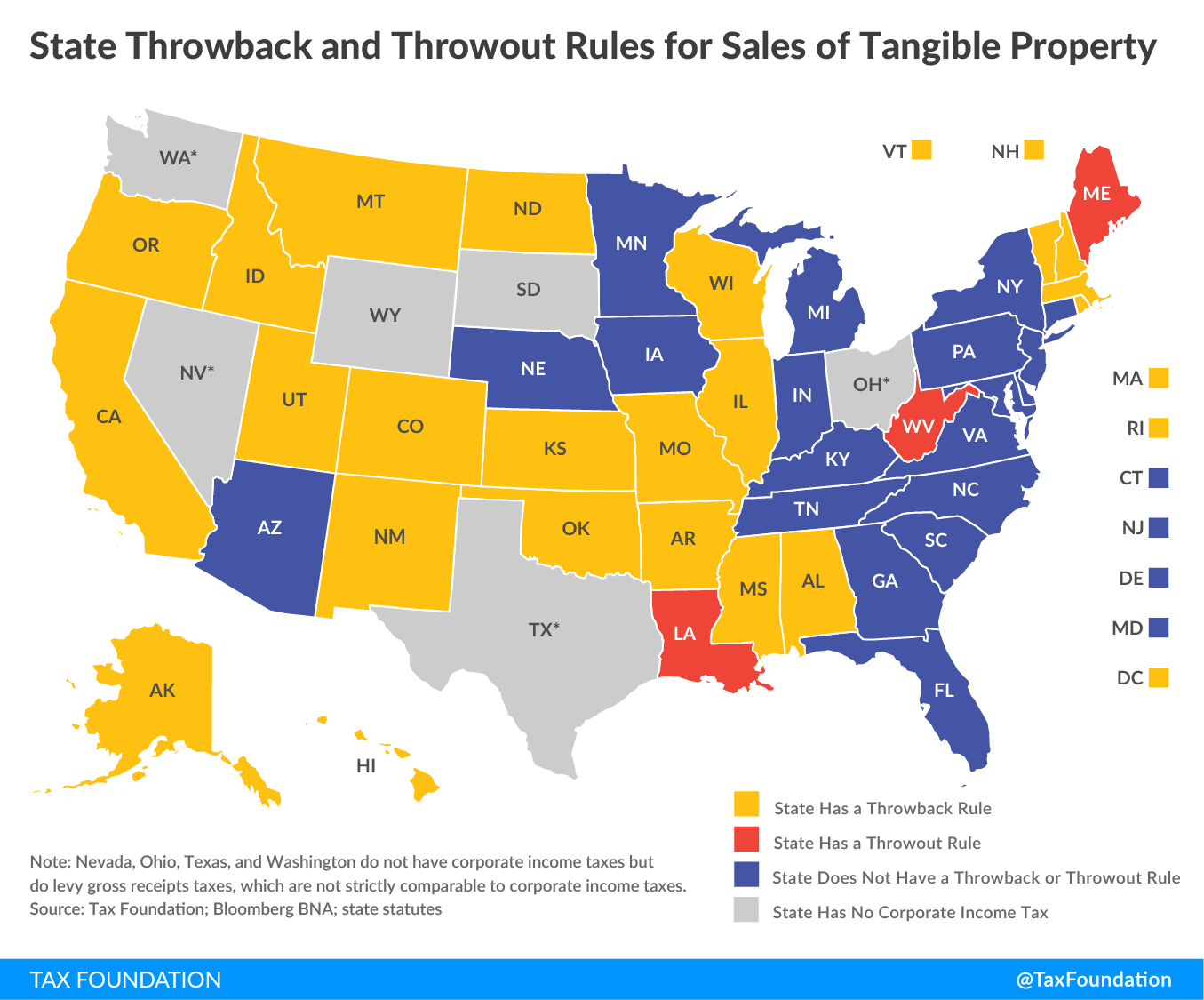

For example, Massachusetts uses single sales factor apportionment for manufacturing business income as an incentive to manufacturing companies to locate their payroll and property in Massachusetts while making significant sales to other states. However, Massachusetts’ code also disincentivizes those very same companies (and all others) from investing in Massachusetts by levying a capital stock tax based on the company’s assets within Massachusetts. The Commonwealth also imposes a limited version of a corporate income “throwback rule” upon businesses, bringing some of the income these businesses generate from sales into other states back into their Massachusetts income base. Thus, some provisions of Massachusetts’ corporate code are incentivizing manufacturers to locate payroll and property in Massachusetts while selling product into other states, and other provisions are punishing them for locating property in Massachusetts and selling product into other states. Massachusetts policy officials should decide what they want the tax code to incentivize, and streamline it thus.

Furthermore, while financial services companies receive the benefit of single sales factor apportionment, the Commonwealth taxes them at a higher rate (9 percent) than non-financial companies (8 percent). These contradictory measures, which affect not only manufacturing and financial services companies, reveal a non-neutral corporate tax code with some provisions that incentivize and others that disincentivize businesses to invest and grow in the Commonwealth.

Massachusetts should reduce, cap, or eliminate its highly uncompetitive capital stock tax, and repeal its self-defeating corporate throwback rule. Massachusetts’ capital stock tax is $2.60 per $1,000 of a corporation’s assets within the commonwealth, with differences in how valuation occurs based on whether the company is a tangible or intangible property corporation.

The majority of states forgo the outdated capital stock tax altogether, with several states having repealed theirs in recent years, and with repeal scheduled or underway in New York, Connecticut, Illinois and Mississippi. Capital stock taxes are especially pernicious for small businesses and for companies that have lots of assets but low or no profits. The tax incentivizes profit-stripping and disincentivizes re-investment in the Commonwealth. Of all the states that are not in the process of repealing their capital stock tax, Massachusetts has the third-highest rate (0.26 percent), behind Arkansas and Louisiana (0.3 percent each).

|

(a) Taxpayer pays the greater of corporate income tax or capital stock tax liability. (b) The tax will be phased out from 2021 to 2026. (c) Based on a fixed dollar payment schedule. Effective tax rates decrease as taxable capital increases. (d) The tax will be phased out from 2020 to 2024. (e) The rate is 0.15% for the first $300,000 of taxable capital. (f) Tax will be fully phased out before 2028. (g) Tax is being phased out; liability limited to liability in tax year ending Dec. 31, 2010. Note: Capital stock taxes are levied on net assets of a company or its market capitalization. Sources: State statutes; Bloomberg Tax. |

||

| State | Tax Rate | Max Payment |

|---|---|---|

| Alabama | 0.18% | $15,000 |

| Arkansas | 0.30% | Unlimited |

| Connecticut (a, b) | 0.34% | $1,000,000 |

| Delaware | 0.04% | $200,000 |

| Georgia | (c) | $5,000 |

| Illinois (d) | 0.10% | $2,000,000 |

| Louisiana (e) | 0.30% | Unlimited |

| Massachusetts | 0.26% | Unlimited |

| Mississippi (f) | 0.23% | Unlimited |

| Nebraska | (c) | $11,995 |

| New York (a,g) | 0.05% | $5,000,000 |

| North Carolina | 0.15% | Unlimited |

| Oklahoma | 0.13% | $20,000 |

| South Carolina | 0.10% | Unlimited |

| Tennessee | 0.25% | Unlimited |

| Wyoming | 0.02% | Unlimited |

Finally, Massachusetts’ limited throwback rule is counterproductive and worth taking off the books. Throwback rules seek to take what is called “nowhere income,” which is income generated in a state without jurisdiction to tax it, and bring that income back into a home state’s corporate tax baseThe tax base is the total amount of income, property, assets, consumption, transactions, or other economic activity subject to taxation by a tax authority. A narrow tax base is non-neutral and inefficient. A broad tax base reduces tax administration costs and allows more revenue to be raised at lower rates. . However, research shows that these rules generate no long-term revenue for a state because of how they incentivize economic distortions and avoidance via supply chain restructuring. The “Massachusetts rule” for throwback is already limited compared to other states, and the Commonwealth would do well to eliminate throwback altogether.

Eliminating the capital stock tax and repealing the throwback rule will streamline Massachusetts’ corporate tax code, make it more neutral, and incentivize investment and economic growth.

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

Subscribe