Download Fiscal Fact No. 406: Inflation Can Cause an Infinite Effective Tax Rate on Capital Gains

Introduction

The United States’ federal top capital gains taxA capital gains tax is levied on the profit made from selling an asset and is often in addition to corporate income taxes, frequently resulting in double taxation. These taxes create a bias against saving, leading to a lower level of national income by encouraging present consumption over investment. rate is now 23.8 percent due to two taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. increases at the start of 2013.[1] This is problematic, because the capital gains tax creates a bias against savings, slows economic growth, and places a double-tax on corporate profits. Although these problems with the capital gains tax are well known, there is a more subtle issue with the tax that makes it even worse for taxpayers than these conventional concerns suggest.

Under the federal tax code, the increase in an asset’s price is determined as the nominal amount (i.e., not adjusted for inflation). When an asset (often a stock) is sold above its purchase price, a gain is realized and is taxed. Any capital gain due to inflationInflation is when the general price of goods and services increases across the economy, reducing the purchasing power of a currency and the value of certain assets. The same paycheck covers less goods, services, and bills. It is sometimes referred to as a “hidden tax,” as it leaves taxpayers less well-off due to higher costs and “bracket creep,” while increasing the government’s spending power. is not accounted for, and the taxpayer is taxed on both their increase in income and on increases in prices economy-wide. As a result, the effective tax rate on the real (inflation indexed) capital gain has exceeded the statutory rate every year since 1950 and has averaged around 42 percent.

In some instances, the practice of taxing the nominal gain can lead to an infinite effective rate on real capital gains when the increase in price is only due to inflation. In fact, if a taxpayer purchased an average stock in 1999, 2000, or 2007 and sold in 2013, they would be taxed entirely on inflation.

The S&P 500 Since 1950

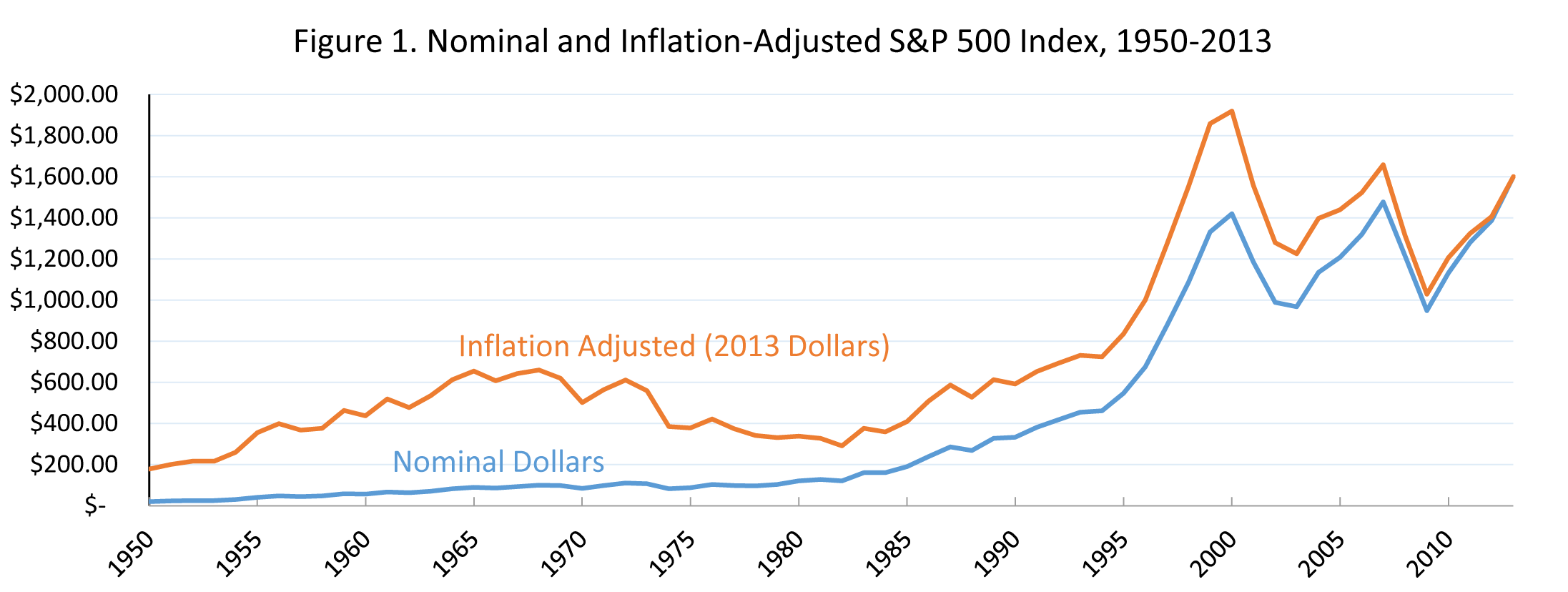

Over the past sixty years, the stock market has grown immensely in nominal terms. Figure 1 shows the nominal and inflation-adjusted value of the S&P 500 index from 1950 to 2013.[2] In nominal terms, the S&P 500 grew from $18.43 in 1950 to $1,601.15 in 2013, an increase of 8,587 percent.[3] Most of the growth of the S&P 500 happened in the 1990s when the value of the index grew from $332.68 in 1990 to $1,419.73 in 2000, a 327 percent increase. In the 2000s, the market became volatile, crashing from a record high twice, though it still nominally grew to its highest point in history in 2013. What this means is that if an individual purchased an average stock any year between 1950 and 2012 and sold it in 2013, they would realize a nominal capital gain.

However, after adjusting the value of the S&P 500 for inflation, some of these nominal gains become real losses. While it is true that from 1950 to 2013, the S&P 500 still experienced tremendous growth of about 800 percent, it actually peaked in 2000 in real terms and has yet to recover from its two crashes in the 2000s.[4] In other words, individuals who purchased stock at or around the peaks of 2000 and 2007 actually realized a real capital loss if they sold the asset in 2013.

The Taxation on Inflation

When an individual buys a stock and later sells it for a capital gain, they must pay tax on this income. For instance, suppose an individual purchased an average stock valued at $7.51 in 1980 and sells this stock in 2013 for $100.[5] As a result, he realized a capital gain of $92.49 and must pay the 23.8 percent tax[6] of $22.01 on this nominal gain. However, since there was inflation during this period, the real gain was actually only $78.79. This implies that the taxpayer paid an effective rate of 27.9 percent on the real gain.[7]

However, the amount of tax owed due to inflation or a real gain is not the same each year. Figure 2 demonstrates how inflation affected the long-term capital gains[8] tax owed on an average stock purchased in a given year and sold in 2013.[9] The S&P 500 has been indexed to 100.[10] Each bar in Figure 2 measures the proportion of tax that is due to inflation (red) versus any real gain (blue). As the figure indicates, the proportion of tax due to inflation varies year to year. For instance, if a taxpayer purchased an average stock in 1950 and sold it in 2013 for $100, she would pay a $2.39 tax on inflation and $21.14 on a real gain. In contrast, a taxpayer who purchased an average stock in 1967 and sold it in 2013 for $100 would pay $8.22 on inflation and $14.20 on a real gain.

Some Taxpayers May be Taxed Entirely on Inflation, not Income

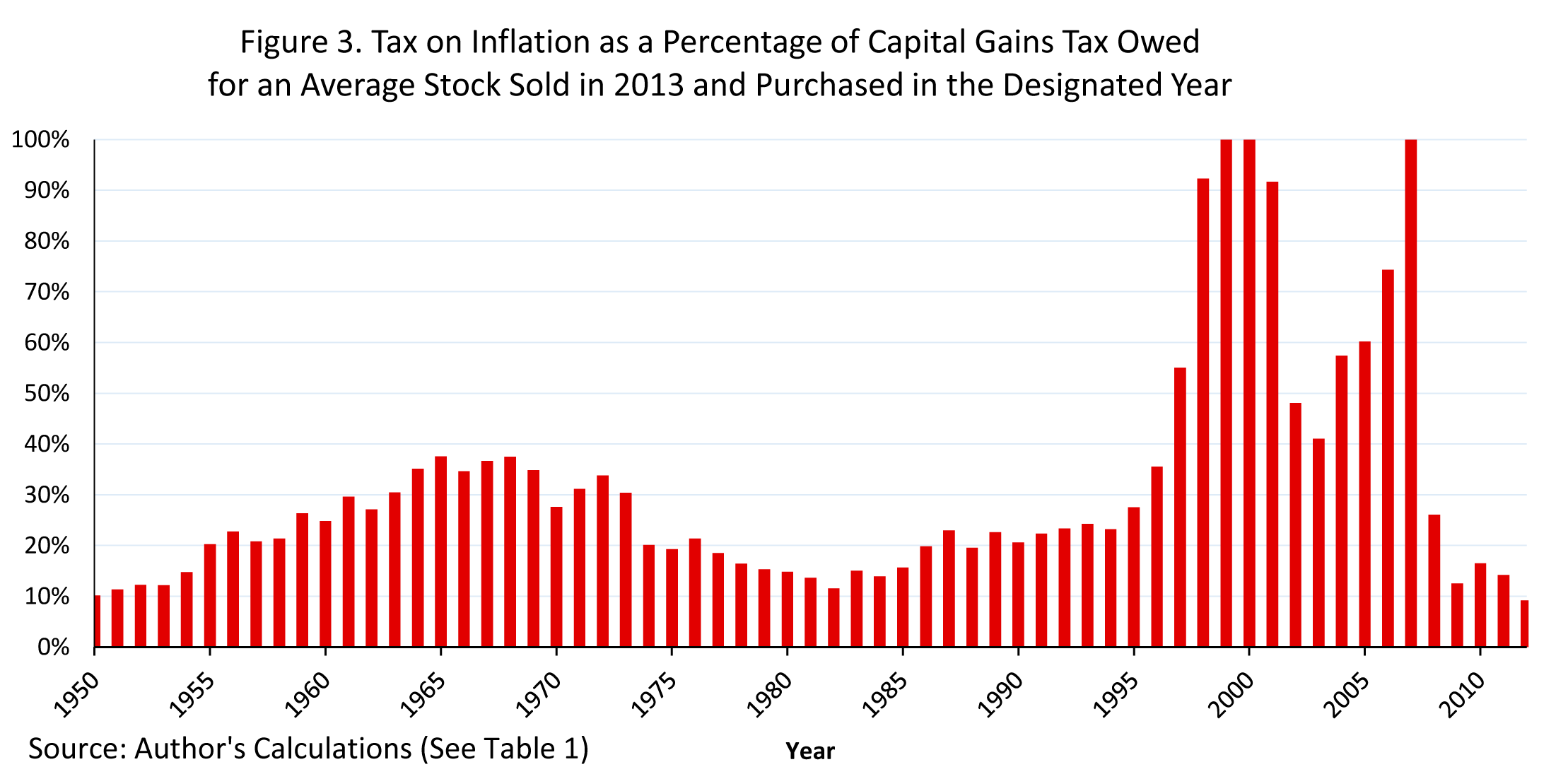

When stocks are bought at particular high points in the market, inflation can account for 100 percent of the capital gains tax owed. In fact, the inflationary increase in price can cause a nominal capital gain for a taxpayer despite suffering a capital loss in real terms. Figure 3 illustrates the percent of the capital gains tax owed due to inflation. The tax paid on inflation as a percent of a taxpayer’s total tax bill is relatively small if the stock were bought in the 1950s or in the 1980s due to the real increase in the value of the market since those decades. In contrast, the average stock bought in 1999, 2000, or 2007 would yield real losses if sold in 2013 but nominal gains on the order of 19.6, 12.1, and 7.7 percent respectively. The capital gains tax owed on the average stock bought during these years is solely due to inflation.

The Tax on Real Gains has Exceeded the Statutory Rate Every Year Since 1950

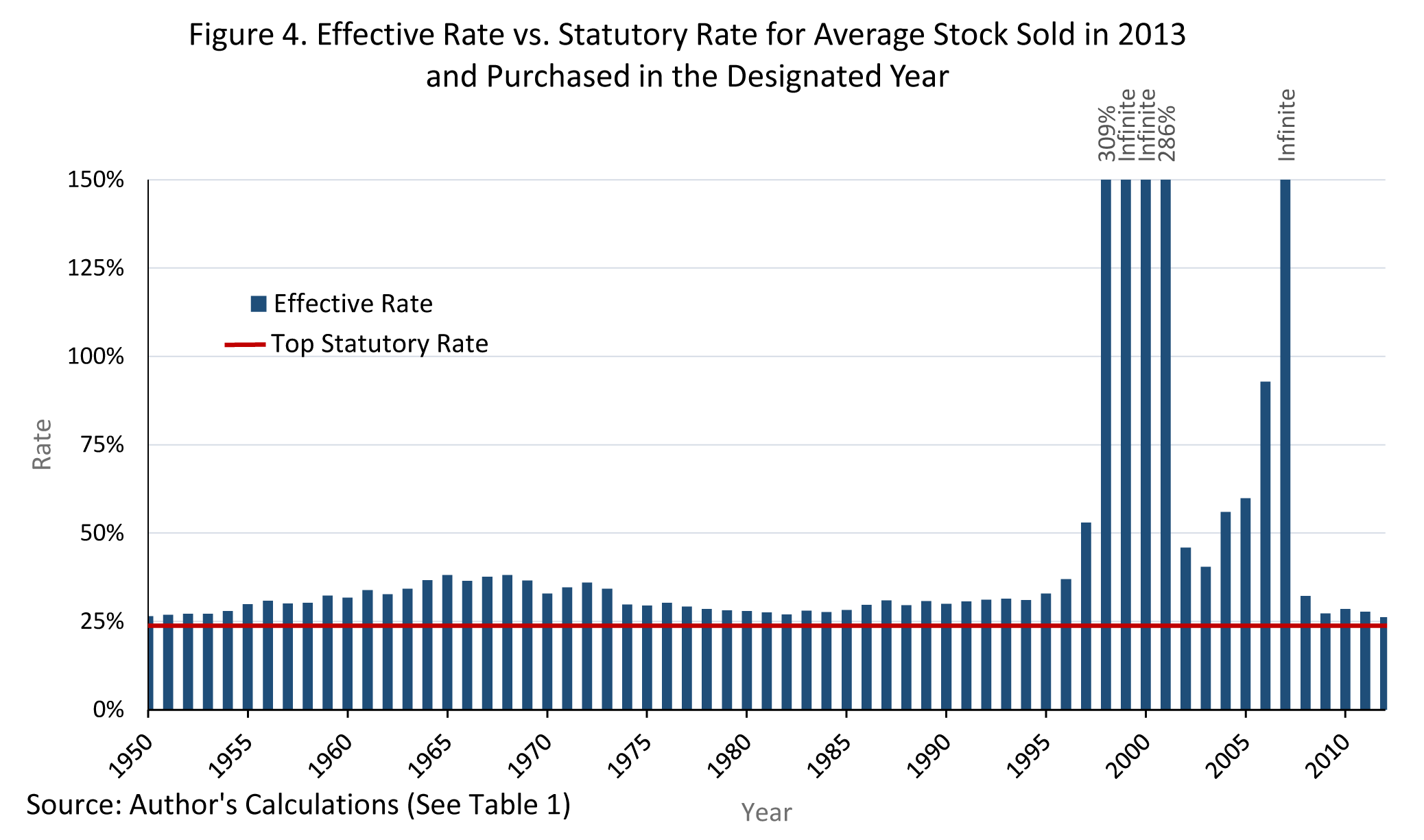

Since inflation has been an ever-present phenomenon in the economy, it has affected the taxes owed on long-term capital gains every year since 1950. As a result, the effective rate on real capital gains has exceeded the statutory rate every year since 1950. Figure 4 shows the effective rates for stock purchases between 1950 and 2012 compared to the top statutory rate of 23.8 percent. The effective rate on real gains varied between 26.4 percent for a stock purchased in 1950 and 309 percent for stocks purchased in 1998. For stocks purchased in 1999, 2000, and 2007, the nominal price of the stock increased while the real value declined. As a result, the effective rate is infinite. The average effective rate on real gains from 1950 to 2012 was 42.5 percent,[11] nearly twice the statutory rate.

Policy Fixes

Taxpayers can end up paying a very high tax rate on capital gains and can even pay taxes on capital gains when the real value of their investment has actually declined. In fact, research from the 1980s showed that taxpayers paid an additional $500 million in extra tax due to inflation in just 1973.[12] Taxes on capital damage economic growth, and failing to account for inflation exacerbates the damage.[13] Outlined below are some possible solutions to the problem.

Repealing the Capital Gains Tax

In order to stop the damaging practice of taxing individuals on inflation, one solution would be to repeal the capital gains tax altogether. In an ideal world we would eliminate both the capital gain tax and the dividend tax as they create double taxationDouble taxation is when taxes are paid twice on the same dollar of income, regardless of whether that’s corporate or individual income. . High taxes on capital cause lower overall investment and higher consumption. This tax bias toward consumption over investment slows economic growth over the long term.[14]

Repealing the capital gains tax would be a pro-growth change and produce positive long-term dynamic effects for the economy. A decrease in the cost of capital would increase the amount of capital available for investment, improving the productivity of business and raising average wages.

Indexing Capital Gains

However, outright repeal of the capital gains tax may be politically impractical. In this case, the second-best solution would be to index capital gains to inflation. While keeping the current tax on capital gains in place, taxpayers could be able to index the basis of their gain to inflation. In order to index the long-term capital gains tax, applicable inflation ratios stretching back several years would need to be determined annually (such as those shown in column D of Table 1 in the Appendix), so that the taxpayer could adjust the basis (purchase price) of the asset in order to compute their real capital gain. This would not be so different from the inflation factor the IRS determines annually for calculating the increase in brackets, thresholds, and deductions for the personal income tax.

Capital gains have historically been given a preferential rate over ordinary income, and there has been some discussion that this lower rate exists to account for the lack of inflation indexing. This argument is not logically consistent since some taxpayers still end up being taxed on real losses, and the average effective rate on real capital gains of 42.5 percent is higher than the top personal income tax rate of 39.6 percent. The motives behind lower rates on capital gains are separate from the impact of inflation on the tax. Indexing would address the current disconnect between the tax levied and whether the taxpayer actually made a profit or loss.

Unfortunately, this alteration to the tax code would bring more complexity. There is already an excess of rules with regard to determining the correct basis and sales price in addition to the types of assets and transactions to which the tax applies. The additional inflation adjustment would complicate the code even further. Inflation indexingInflation indexing refers to automatic cost-of-living adjustments built into tax provisions to keep pace with inflation. Absent these adjustments, income taxes are subject to “bracket creep” and stealth increases on taxpayers, while excise taxes are vulnerable to erosion as taxes expressed in nominal dollars, rather than rates, slowly lose value. would also accentuate the periodic nature of the revenues from this tax,[15] which results from the business cycle, since there would be far fewer real capital gains than nominal capital gains during a recessionary period.

Conclusion

The capital gains tax is more damaging than other taxes because of the bias it creates towards consumption over savings and investment. By applying the tax on a nominal basis, many further detrimental effects are caused, including an average effective rate on real capital gains that exceeds the top personal income tax rate, despite the preferential statutory rate capital gains receive. In certain situations, taxpayers face an infinite rate on real capital gains when the tax is solely due to inflation. While repealing this tax would be the preferable option, inflation indexing would be an improvement that would link the tax to real increases in income rather than increases in inflation.

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

SubscribeAppendix

The effective rate on real capital gains shown in Table 1 is the tax rate based on the actual tax owed on the nominal gain and the inflation indexed capital gain (or real capital gain). For example, a stock bought in 1997 has a nominal capital gain of $44.98 (column B), leading to a capital gains tax of $10.71 (column C) being owed at the current top rate of 23.8 percent. Inflation indexing the value of the average stock gives the stock price in today’s dollars and, from that, the inflation indexed capital gain of $20.23 (column E). Dividing the nominal capital gains tax owed of $10.71, by the real capital gain of $20.23, gives 53 percent, or the effective rate that a taxpayer would be obligated to pay on their real capital gain.

[1] The top capital gains tax rate was increased from 15 percent to 20 percent on January 1, 2013 due to the passage of H.R. 8. An additional 3.8 percent net investment tax took effect on the same day in accordance with the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act.

[2] S&P 500 Historical Prices, Yahoo! Finance, http://finance.yahoo.com/q/hp?s=%5EGSPC+Historical+Prices.

[3] The 2013 average is the value up to August 2013.

[4] Bureau of Labor Statistics, Consumer Price Index, http://www.bls.gov/cpi/.

[5] Assuming the stock grew at the same rate as the S&P 500 during that ten-year period.

[6] As of January 1, 2013, the top tax rate on capital gains is 23.8 percent. This hypothetical assumes that he taxpayer’s AGI exceeds $200,000.

[7] The effective rate is found by dividing the tax of $22.01 by the real gain of $78.79.

[8] Long-term capital gains (and losses) are realized on assets held for longer than one year.

[9] The average stock is represented by the S&P 500.

[10] Year 2013 is set to 100.

[11] Excluding years with infinite effective rates.

[12] Martin Feldstein & Joel Slemrod, Inflation and the Excess Taxation of Capital Gains on Corporate Stock, in Inflation, Tax Rules, and Capital Formation (Univ. of Chicago Press, 1983), http://www.nber.org/chapters/c11332.pdf.

[13] Michael Schuyler & Stephen J. Entin, Case Study #3: Reduced Tax Rates on Capital Gains and Qualified Dividends, Tax Foundation Fiscal Fact No. 381 (July 31, 2013), https://files.taxfoundation.org/docs/ff381.pdf.

[14] William McBride, How Tax Reform Can Address America’s Diminishing Investment and Economic Growth, Tax Foundation Fiscal Fact No. 395 (Sept. 23, 2013), https://files.taxfoundation.org/docs/ff395.pdf.

[15] William McBride, The Great RecessionA recession is a significant and sustained decline in the economy. Typically, a recession lasts longer than six months, but recovery from a recession can take a few years. and Volatility in the Sources of Personal Income, Tax Foundation Fiscal Fact No. 316 (June 13, 2012), https://files.taxfoundation.org/docs/ff316.pdf.