Key Findings

- The TaxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) removed investment barriers by allowing businesses to immediately deduct the cost of certain investments under a provision called 100 percent bonus depreciationBonus depreciation allows firms to deduct a larger portion of certain “short-lived” investments in new or improved technology, equipment, or buildings in the first year. Allowing businesses to write off more investments partially alleviates a bias in the tax code and incentivizes companies to invest more, which, in the long run, raises worker productivity, boosts wages, and creates more jobs. .

- However, seemingly due to legislative oversight, the law accidentally excluded the category of improvement property investment from 100 percent bonus depreciationDepreciation is a measurement of the “useful life” of a business asset, such as machinery or a factory, to determine the multiyear period over which the cost of that asset can be deducted from taxable income. Instead of allowing businesses to deduct the cost of investments immediately (i.e., full expensing), depreciation requires deductions to be taken over time, reducing their value and discouraging investment. . As a result, investments of this type face a higher tax burden than under prior law.

- More restrictive cost recoveryCost recovery refers to how the tax system permits businesses to recover the cost of investments through depreciation or amortization. Depreciation and amortization deductions affect taxable income, effective tax rates, and investment decisions. treatment for interior improvements to buildings will increase costs and discourage companies from making these types of investments.

- All business expenses should be immediately deductible, including the amount that businesses spend on investment.

- Policymakers should work to ensure that cost recovery for qualified improvement property (QIP) does not remain worse off due to technical drafting errors, and that it is eligible for 100 percent bonus depreciation.

Introduction

Removing barriers to business investment in the United States was one of the central goals of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), enacted last December. One of the key provisions in the bill, known as “100 percent bonus depreciation,” allows businesses to immediately deduct the cost of short-lived investments—limiting the penalty that the federal tax code placed on businesses that make capital investments in the United States.

However, the law excludes some categories of business investment from 100 percent bonus depreciation. For instance, many interior improvements to buildings are not eligible for the provision, and will be required to be written off over time periods as long as 39 years. This exclusion is widely believed to have been due to a legislative oversight: Congress seems to have intended building improvements to be eligible for 100 percent bonus depreciation, but left them out due to a last-minute drafting error. As a result, the new tax law actually worsens the tax treatment of this type of investment, which previously qualified for bonus depreciation, by reducing the ability of businesses to deduct their full building improvement costs.

Ideally, all business expenses should be immediately deductible, including the amount that businesses spend on capital investment. As such, the exclusion of building improvements from the benefit of 100 percent bonus depreciation—whether accidental or not—is unjustified. Policymakers should act to ensure that qualified improvement property is eligible for 100 percent bonus depreciation; at a minimum, they should make sure that the rules for deducting the cost of building improvements do not become more restrictive than they previously were.

Overview of Expensing

Under the U.S. tax code, businesses can generally deduct their ordinary business costs when figuring their income for income tax purposes. However, this is not always the case for the costs of capital investments, such as equipment, machinery, and buildings. Typically, when businesses incur these sorts of costs, they must deduct them over several years according to depreciation schedules instead of immediately in the year the investment occurs.[1]

This system that requires businesses to deduct their capital expenditures over time rather than immediately is quite complicated and means businesses cannot fully recover the cost of those investments. The disallowed portion of cost recovery understates costs and overstates profits, which leads to greater tax burdens. The tax code increases the cost of capital, which leads to less capital investment and lower employment, output, and wages.

Full expensing, however, allows businesses to immediately deduct 100 percent of the cost of their capital expenses. Thus, it removes a bias against investment in the tax code and lowers the cost of capital, encouraging business investment.

Qualified Improvement Property

Prior to the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, the tax code categorized certain interior building improvements into different classes: qualified leasehold improvement property, qualified restaurant property, and qualified retail improvement property. Under prior law, assets with lives of 20 years or less were eligible for 50 percent bonus depreciation. While most building improvements are generally depreciable over 39 years, improvements meeting these category definitions were eligible for a 15-year cost recovery period and thus eligible for 50 percent bonus depreciation under old law.[2]

Improvement property generally includes interior improvements made in buildings that are nonresidential real property. If a business invested in new lighting, exit signs, or woodwork, these investments would generally be categorized as improvement property. Or consider a restaurant or retail store, perhaps with lots of foot traffic, and as a result it needs new permanent floor coverings; such an investment would also generally be qualified improvement property. The definition excludes improvements made to enlarge a building, for an elevator or escalator, or to the internal structural framework of a building.[3]

The PATH Act of 2015 created a fourth category, qualified improvement property (QIP), to extend bonus depreciation to additional improvements to building interiors.[4] Under this new definition, unlike the other three types of improvement property, eligibility did not require that QIP investments be made under a lease. It also did not require a three-year lag between when the building was first placed in service and when the improvement property was placed in service.

A notable feature of QIP, however, was that it did not have a cost recovery period of 15 years; for QIP to be recovered over a 15-year period, it had to also meet the definition of one of the other three types of improvement property.[5] This means that in some instances, QIP may have qualified for bonus depreciation, but the remaining basis would have been depreciated over a 39-year period. This created complexity across different categories and definitions of improvement property.

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

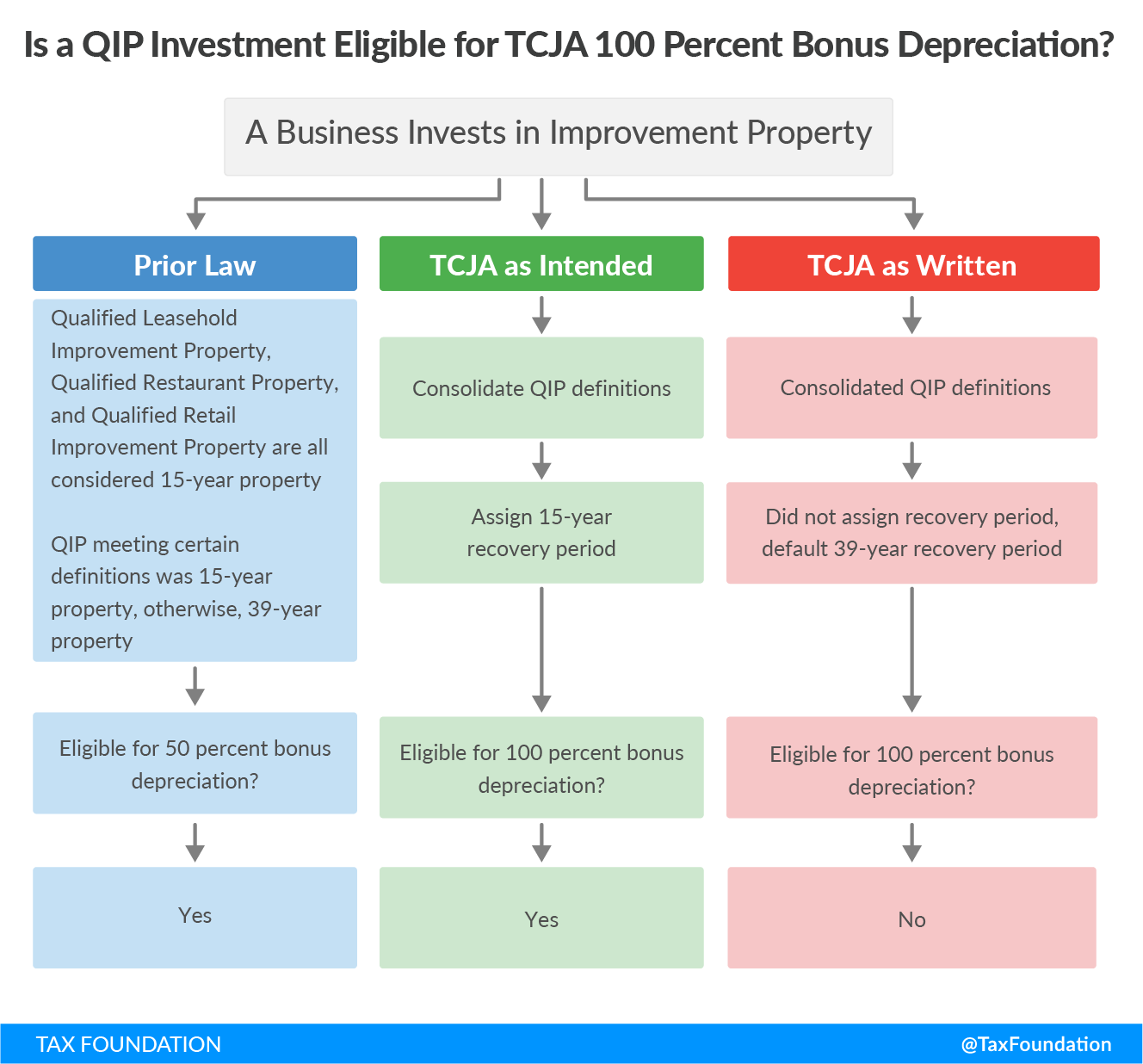

SubscribeThe TCJA Makes Cost Recovery for QIP More Restrictive

The TCJA, in addition to enacting 100 percent bonus depreciation for certain assets with a 20-year recovery period or shorter, made changes intended to simplify the tax code. Among these changes was the consolidation of the different types of improvement property under the single definition of Qualified Improvement Property, with intent to assign this new category a 15-year recovery period, eligible for 100 percent bonus depreciation. The wording of the final bill, however, fails to provide a recovery period, and as a result unintentionally makes QIP ineligible for 100 percent bonus depreciation.

Reviewing the Joint Explanatory Statement of the Committee of Conference provides some insight as to what lawmakers intended to do with improvement property.[6] The Senate version going into the Conference Committee would consolidate the different definitions and assign a shorter, 10-year recovery period:[7]

As a conforming amendment, the provision replaces the references in section 179(f) to qualified leasehold improvement property, qualified restaurant property, and qualified retail improvement property with a reference to qualified improvement property. Thus, for example, the provision allows section 179 expensing for improvement property without regard to whether the improvements are property subject to a lease, placed in service more than three years after the date the building was first placed in service, or made to a restaurant building.

During the Conference Committee, lawmakers made some changes to the Senate version to arrive at a final proposal, explained here:[8]

Senate Amendment: The provision eliminates the separate definitions of qualified leasehold improvement, qualified restaurant, and qualified retail improvement property, and provides a general 10-year recovery period for qualified improvement property, and a 20-year ADS recovery period for such property.

Conference Agreement: The conference agreement follows the Senate amendment….In addition, the conference agreement provides a general 15-year MACRS recovery period for qualified improvement property.

Recall that for property to qualify for the TCJA’s 100 percent bonus depreciation provision, it must be property “with an applicable recovery period of 20 years or less.”[9] The conference agreement clearly intended to simplify the classifications of improvement property under the single heading of Qualified Improvement Property and assign a recovery period of 15 years to make QIP eligible for the new 100 percent bonus depreciation provision.

The final changes made to legislative text did succeed in this first effort: it removed the separate categories of improvement property and added the new QIP definition. However, the changes to make QIP eligible for 100 percent bonus depreciation did not occur. The conference agreement removed the 10-year language from the Senate amendment but then failed to add the 15-year language decided during the Conference Committee. Also, it did not adequately update the 20-year language for the alternative recovery period. The result leaves the newly defined QIP category without an assigned recovery period, while the alternative recovery period definition references a 10-year period provision that does not exist in the final law.

What this means for QIP is that without an assigned recovery period, QIP will in most cases be treated as nonresidential real property with a 39-year recovery period (and 40-year alternative recovery period)—making QIP ineligible for 100 percent bonus depreciation

Figure 1.

Table 1 compares prior law with the intent of the TCJA and the outcome of the TCJA; though the Conference Agreement clearly meant to improve the cost recovery treatment of QIP, as it stands now, cost recovery was made more restrictive.

| Source: Author’s calculations. Assumes half-year convention and 3.5 percent real discount rate plus inflation. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Depreciation Allowances for a $100 Investment | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prior Law | Intent of the TCJA | Current Law | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

15-year asset eligible for 50% bonus depreciation |

15-year asset eligible for 100% bonus depreciation |

39-year asset ineligible for bonus depreciation |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

0% inflation |

$89.06 | $100.00 | $55.06 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

2% inflation |

$84.38 | $100.00 | $42.12 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Had the definitions of improvement property not been consolidated, investments in qualified improvement property would have been eligible for 100 percent bonus depreciation as they were for bonus depreciation under prior law. Instead, in what is seemingly a drafting error, businesses that invest in improvement property will face a higher tax burden under the new law despite the indicated legislative intent to improve the cost recovery treatment of improvement property (see Table 2).

| Source: Author’s calculations. Assumes half-year convention and 3.5 percent real discount rate plus inflation. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Prior Law | Current Law | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

15-year asset eligible for 50% bonus depreciation, 35 percent corporate tax rate |

39-year asset ineligible for bonus depreciation, 21 percent corporate tax rate |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

QIP Investment |

$100.00 | $100.00 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Allowable Deduction |

$84.38 | $42.12 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Disallowed Cost Recovery |

$15.62 | $57.88 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Tax on Disallowed Cost Recovery |

$5.47 | $12.15 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Economics of 100 Percent Bonus Depreciation

One of the most significant changes of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act was to allow 100 percent bonus depreciation for assets with lives of 20 years or less.[10]

As enacted by the TCJA, 100 percent bonus depreciation allows businesses to immediately deduct the full cost of most short-life business investments (such as machinery and equipment), although not long-life assets like structures, which would be deductible under full expensing.[11] When companies are instead required to deduct the cost of their investments over a number of years, the value of the depreciation deduction declines over time, making businesses unable to fully recover the cost of the initial investment.[12]

| Source: Author’s calculations. Assumes half-year convention, 3.5 percent real discount rate, plus inflation. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 15-year asset | 39-year asset | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Full expensing |

$100.00 | $100.00 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

MACRS at 0% inflation |

$76.14 | $55.06 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

MACRS at 2% inflation |

$67.26 | $42.12 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

MACRS at 3% inflation |

$64.72 | $37.24 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

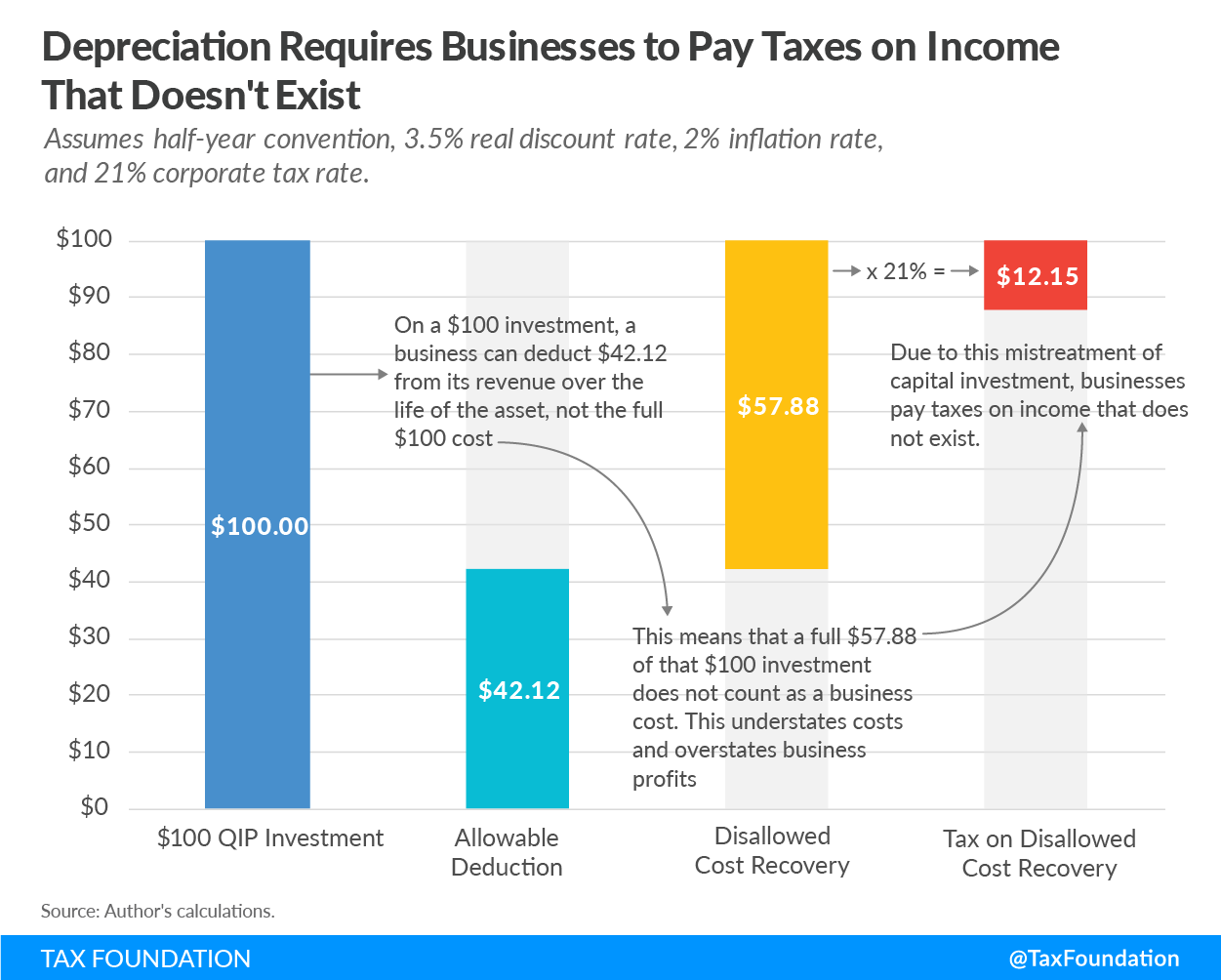

For example, under the TCJA 100 percent bonus depreciation provision, if a company makes a qualifying $100 capital investment it would immediately deduct the full cost of that investment. However, if the investment is not eligible for 100 percent bonus depreciation, the company must take depreciation allowances, preventing full recovery of the cost of the investment. Consider that capital investments in structures—one type of investment that does not qualify for 100 percent bonus depreciation under the TCJA—must be depreciated over a 39-year period. As noted in Table 3, the present value of this type of investment falls from $100 under 100 percent bonus depreciation to as low as $37.24—meaning in some instances businesses are unable to recover even half of their initial investment costs. This treatment understates costs and overstates profits, which in turn leads to a greater tax burden that increases the cost of making those types of investments.

Figure 2.

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

SubscribeThis treatment discourages businesses from making capital investments because they are unable to fully recover their costs.[13] Businesses in this situation, with the inability to fully deduct the cost of their investments, face higher tax burdens because their profits are overstated.[14] Figure 2 illustrates this for a $100 investment in a property that is not eligible for 100 percent bonus depreciation. Under current law, businesses would only be able to deduct $42.12 of their initial $100 investment over the 39-year recovery period, while the remaining $57.88 of costs would never be subtracted from revenue. The business would owe income tax on the overstated profit, resulting in a present value tax burden of $12.15, on income that doesn’t exist, which reduces the rate of return on the $100 investment. One hundred percent bonus depreciation removes this bias against investment.

QIP Should be Eligible for 100 Percent Bonus Depreciation

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, while effectively removing tax barriers to many categories of business investment, created new barriers for investing in qualified improvement property, seemingly by mistake. Businesses making investments to improve their property now face a more restrictive cost recovery period—more than twice than under prior law—and are excluded from 100 percent bonus depreciation. These businesses will face a higher tax burden on QIP investments than under previous law, an outcome that could have significant consequences, potentially slowing investment, employment, and output for those affected.

The tax burden on building improvements should not have worsened due to tax reform. Policymakers should work to extend 100 percent bonus depreciation to qualified improvement property; at a minimum, they should make sure that the rules for deducting the cost of building improvements do not remain more restrictive than under previous law.

[1] Scott Greenberg, “What is Depreciation, and Why Was it Mentioned in Sunday Night’s Debate?” Tax Foundation, October 10, 2016, https://taxfoundation.org/what-depreciation-and-why-was-it-mentioned-sunday-night-s-debate/.

[2] KBKG, “Qualified Improvements – Depreciation Quick Reference (updated 3/2/2018),” https://www.kbkg.com/handouts/KBKG-Qualified-Improvement.pdf.

[3] Tony Nitti, “Tax Geek Tuesday: Changes To Depreciation In The New Tax Law,” Forbes, January 2, 2018, https://www.forbes.com/sites/anthonynitti/2018/01/02/tax-geek-tuesday-changes-to-depreciation-in-the-new-tax-law/#914a8f42c4bc.

[4] Eddie Price, “New Qualified Improvement Property Category in 2016,” National Society of Accountants, June 29, 2016, http://www.nsacct.org/blogs/eddie-price/2016/06/29/new-qualified-improvement-property-category-in-2016.

[5] Heather Alley, “PATH Act and Expanded Benefits for Real Property – A Case of True Déjà Vu?” Dixon Hughes Goodman LLP, February 8, 2016, https://www.dhgllp.com/resources/alerts/article/1532/path-act-and-expanded-benefits-for-real-property-a-case-of-true-deja-vu.

[6] “Joint Explanatory Statement of the Committee of Conference,” December 18, 2017, http://docs.house.gov/billsthisweek/20171218/Joint%20Explanatory%20Statement.pdf.

[7] Ibid, 204.

[8] Ibid, 204-205. The 10-year period was increased to a 15-year period in the conference agreement.

[9] Ibid, 181.

[10] Tax Foundation, “Preliminary Details and Analysis of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act,” December 18, 2017, https://taxfoundation.org/final-tax-cuts-and-jobs-act-details-analysis/.

[11] Stephen J. Entin, “Tax Treatment of Structures Under Expensing,” Tax Foundation, May 24, 2017, https://taxfoundation.org/tax-treatment-structures-expensing/.

[12] Amir El-Sibaie, “Latvia Joins the Cash-Flow Tax Club,” Tax Foundation, April 16, 2018, https://taxfoundation.org/latvia-cash-flow-tax/.

[13] Scott Greenberg, “Cost Recovery for New Corporate Investments in 2012,” Tax Foundation, January 2016, 2, /wp-content/uploads/2016/01/TaxFoundation-FF495.pdf.

[14] Stephen J. Entin, “The Tax Treatment of Capital Assets and Its Effect on Growth: Expensing, Depreciation, and the Concept of Cost Recovery in the Tax System,” Tax Foundation, April 2013, https://files.taxfoundation.org/legacy/docs/bp67.pdf.