Companies around the world regularly do business in multiple countries, and they arrange their supply chains and distribution models in various ways. Some businesses rely heavily on physical assets like factories and delivery vehicles, but many businesses also rely on intellectual property and data transfers. In either case, selling goods and services across borders has tax consequences.

Imagine a company based in France that has subsidiaries in Bulgaria and the Cayman Islands. Those subsidiaries could be in Bulgaria and the Cayman Islands for economic reasons or they could be there because France has a high combined corporate taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. rate (34.4 percent) while Bulgaria (10 percent) and the Cayman Islands (0 percent) have rather low rates.

Using various tax planning techniques, the French company could arrange its income streams so that the French headquarters has low profits while the Bulgarian and Cayman Islands subsidiaries are quite profitable. If French authorities only tax the profits that are generated at the headquarters level in France, then the company could minimize its tax burden with its Bulgarian and Cayman Islands offices.

From the French perspective, those subsidiaries are foreign corporations and their earnings might not get taxed in France. Might is the operative word, though.

As is the case with many countries that have systems that only tax income earned within their borders (territorial taxation), France applies Controlled Foreign Corporation (CFC) rules to tax some income of foreign subsidiaries. If the Bulgarian and Cayman Islands subsidiaries are more than 50 percent owned by the French company, then their income could be taxed by France.

To face French taxation, the effective tax rate on the Bulgarian and Cayman Islands earnings would need to be less than half the French effective tax rate. However, if the Bulgarian subsidiary is a manufacturer, the French rules would exempt it from taxation because Bulgaria is an EU member.

For the Cayman Islands subsidiary, on the other hand, it is likely that all its income will be taxable in France given that it is not an EU member state and has a zero percent corporate tax rate. Even if the Cayman Islands subsidiary was a manufacturer and producing physical products, the French rules would apply France’s corporate income tax to all the income from that subsidiary. Without the rules, companies could avoid paying taxes in France at a significant scale.

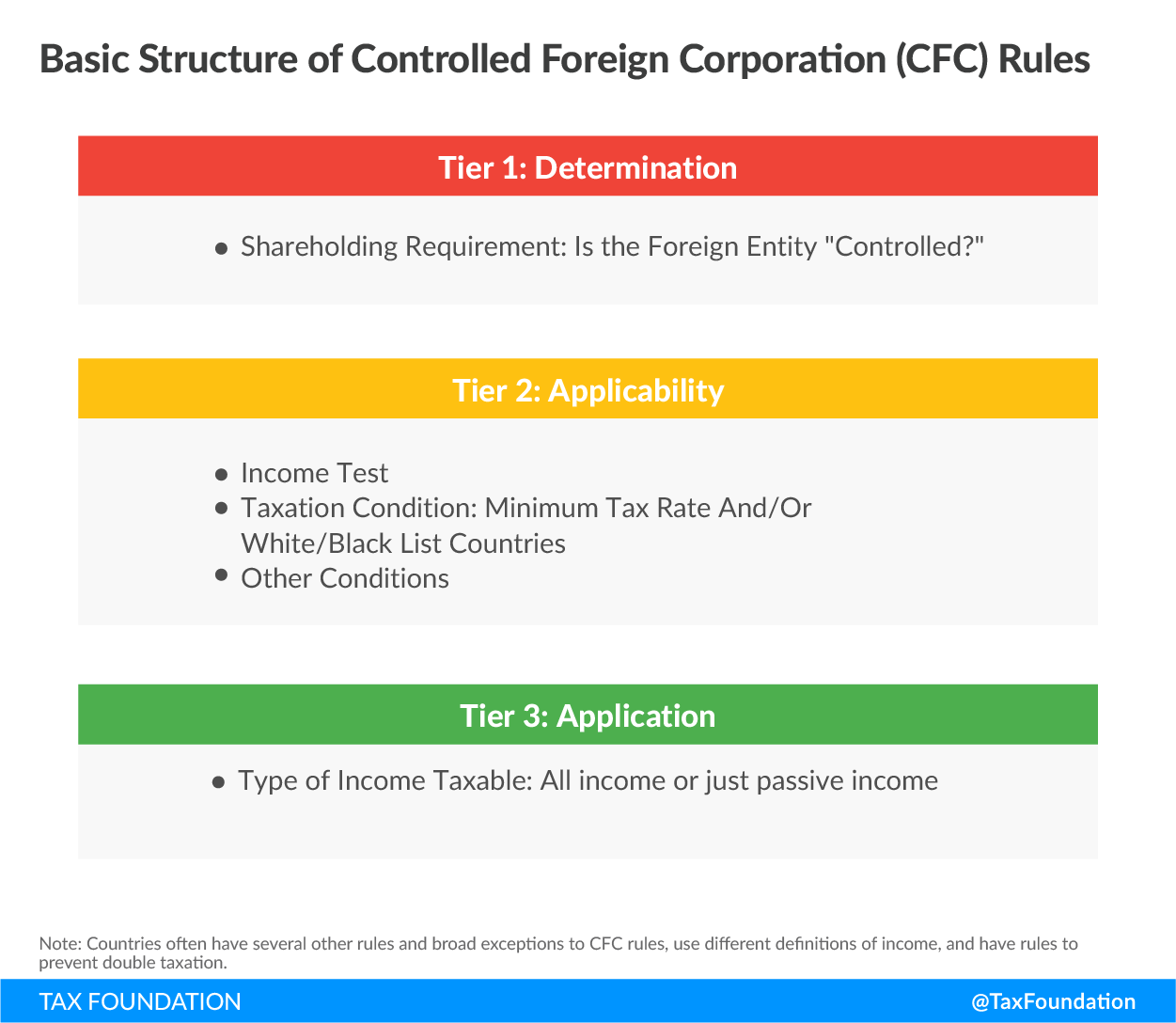

This example is just one of many possible interactions between multinational companies and the rules that countries use to protect their tax bases. Simply put, CFC rules are designed so countries can claim taxing rights over revenue generated in foreign jurisdictions under certain circumstances. They usually follow a structure that includes a definition of “control,” a threshold for applicability of tax, and the type of income that is taxable.

The structure of the rules is really an incentive system. In the French system, there is a sort of competition between France and its companies over how much tax should be paid in France. A company could gain an advantage within the French rules by placing its manufacturing facilities in low-tax EU countries. France plays defense by taxing both investment and manufacturing earnings in countries outside the EU. There is no end to this game, however, since France could change the rules and companies would then react again.

The rules and the reactions to them by businesses can lead to outcomes that are contrary to what might make economic sense in the absence of the rules. As the 2015 OECD report on CFC rules points out, “CFC rules can run the risk of restricting or distorting real economic activity.” Recent research attempts to measure where and how serious those distortions are when they show up.

If France’s CFC rules increase the tax burden on the French company (as they are designed to do), then this could have spillover effects not only into low-tax jurisdictions where subsidiaries may be moved from, but also to higher tax jurisdictions where new subsidiaries may be set up. A higher tax burden could also mean a higher cost to investing and make it more difficult for the company to grow not only in France but also in markets around the world like the United States or India. Untangling these effects is important to understanding the trade-offs that come with CFC rules and other mechanisms that countries use to protect their tax bases.

In a recent paper in the Journal of Public Economics, economist Sarah Clifford identifies specific mechanisms in CFC rules that influence business responses to those rules. Clifford uses the variation of CFC rules across countries and the variation of other tax reforms to measure how businesses react to the rules and study the revenue effects.

As mentioned above, France has a threshold for taxing a foreign subsidiary of a French company an effective tax rate that is 50 percent or less than the French effective rate. Other countries have similar thresholds that are also relative to domestic tax rates. Because the thresholds are relative, changes in domestic corporate tax rates also change the threshold for applying CFC rules.

The paper shows that companies respond to these thresholds by bunching their subsidiary income in tax jurisdictions just above the threshold so they can avoid having income taxed under CFC rules.

Some income streams are easier to shift than other income. If a factory produces a product that is sold directly to a customer, it can be difficult to attribute that factory’s income to a different jurisdiction than where the factory is located. However, financial income (investment income, interest payments) can be more easily shifted from one country to another. If an arrangement where one subsidiary in a low-tax jurisdiction is loaning money to another subsidiary in a high-tax jurisdiction triggers the application of CFC rules, the loan could be rearranged so that the loan is originated from a subsidiary in a country where the CFC rules would not apply.

Clifford estimates that one impact from a reform that moves a subsidiary below the CFC threshold is a 13 percent reduction in financial profit in that subsidiary. By shifting financial income to countries with tax rates just above the CFC threshold, companies can work within the rules to minimize their tax burdens under the new regime.

Clifford finds this effect results in higher tax revenue not only for the countries where the financial profit is shifted to, but also for the country enforcing the CFC rules.

A 2015 paper by economists Peter Egger and Georg Wamser in the Journal of Public Economics estimates the impact of CFC rules on foreign real investment by German firms. According to their work, the incentives embedded in German CFC legislation lead to an estimated €7 million reduction in investments on average in fixed foreign assets (like property, plants, and equipment) by German multinational corporations.

So if, prior to the adoption of the German CFC rules, German firms were investing in assets like subsidiary factories and distribution centers outside of Germany, the CFC rules led to a reduction in those investments, all other things being equal. The authors note, “This suggests that the CFC rule brings about a sharp increase in the cost of capital.”

A third study by economist James Albertus examines how foreign multinational companies with a presence in the United States change their behavior when their home countries enact CFC rules. Albertus estimates that when the U.S. subsidiary of a foreign company becomes subject to a CFC regime the subsidiary reduces investment by 12 percent and employment by 16 percent. Additionally, U.S. subsidiaries subject to foreign CFC regimes reduce their wages for employees by 11 percent.

These studies all lead back to the point made earlier: when the rules of the game change, the players respond. With any policy change there are trade-offs. For governments implementing CFC rules and other policies targeted at reducing tax avoidance, there is evidence that the countries can gain tax revenue. However, increases in the cost of capital and the reduction in employment and cross-border investment are identifiable consequences. If a policy is in the interest of one country due to revenue concerns, it could be at the expense of real investment and jobs in another country.

Governments should recognize these trade-offs as they implement CFC rules or change their tax policies in ways that increase taxes on foreign subsidiaries.

Note: This is part of our Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) blog series