Executive Summary

- Taxpayer protections regarding taxes, such as supermajority thresholds and voter approval requirements, depend on a meaningful definition of “taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. .” The Tax Foundation’s Center for Legal Reform spotlights efforts to evade these constitutional and statutory safeguards, through public education and legal briefs.

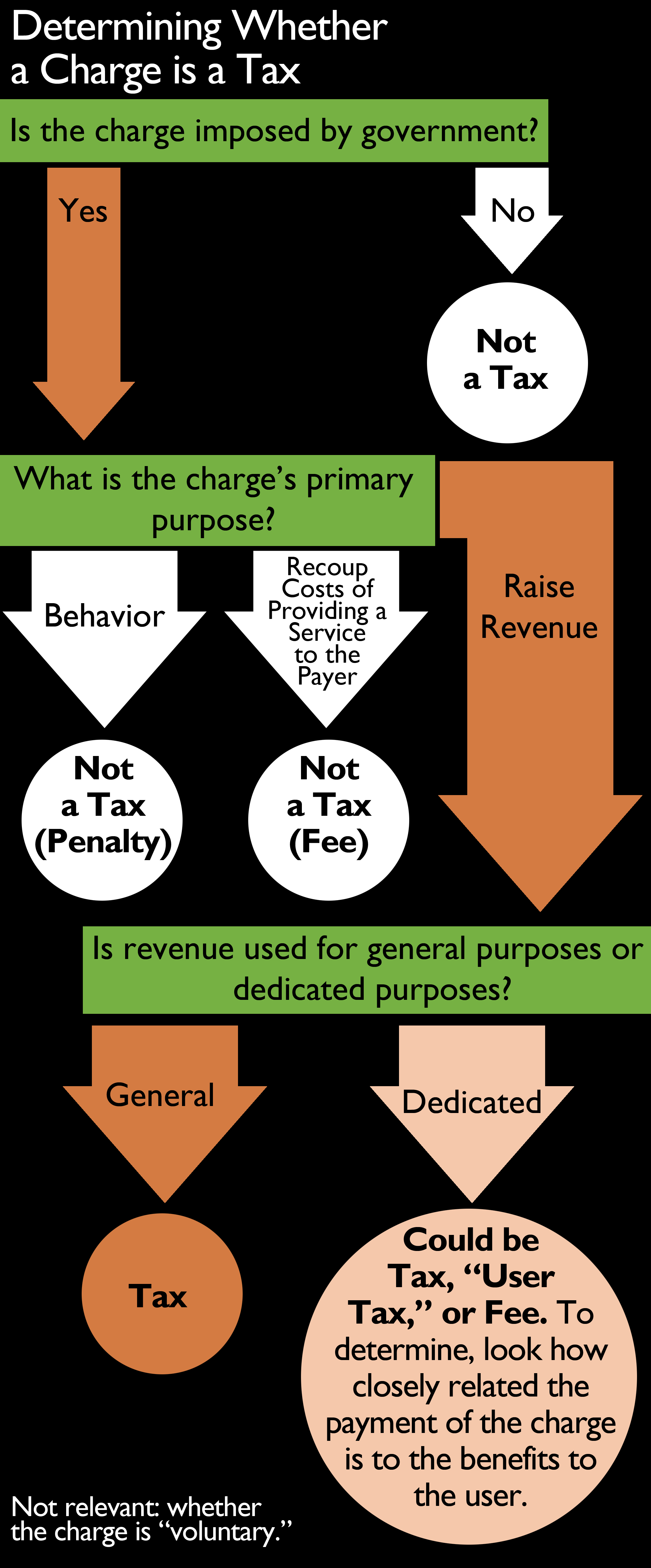

- The public understanding of “tax” aligns with the widely understood definition of a tax as a charge imposed with the primary purpose of raising revenue.

- This is in contrast to a “fee,” a charge imposed for the primary purpose of recouping costs incurred in providing a service to the payer, and a penalty, a charge imposed for the primary purpose of punishing behavior.

- Nearly every state has adopted these definitions (all except North Carolina and Oregon). Ohio is the most recent to adopt them, in a recent case where the Tax Foundation filed a brief.

- All states but one (Oregon) have a rule to resolve any ambiguity in tax statutes in favor of the taxpayer.

- Ten states have explicitly rejected the dangerous “voluntariness” standard for defining taxes while thirteen states use it in part.

- The careful language used in the U.S. Supreme Court’s health care decision suggests that the Court did not seek to overturn its precedent defining “tax,” which aligns with the definitions used in the states.

Introduction

American antipathy to taxes is rooted deep in our nation’s history, from early colonial taxes to the Boston Tea Party to the Whiskey Rebellion to California’s Proposition 13 to today. Elected and appointed officials are increasingly turning to a strategy of hiding increased tax burdens by denying that even an obvious tax is a tax. They label them user fees, fines, surcharges, revenue enhancements, special assessments, and so forth.

This is not just a matter of semantics. Taxes that are not called taxes violate the principle of transparency by depriving taxpayers of information needed to make meaningful choices about public priorities. Further, many state constitutions contain additional procedural steps and limitations that apply only to tax increases. Sixteen states require legislative supermajorities for tax increases; nearly every state requires uniformity in taxation, which means equal treatment of similarly situated taxpayers; and many states have multiple reading requirements or caps on tax rates or revenue levels.

These taxpayer protections can be undermined if the legislature can circumvent them by merely relabeling what would otherwise be a tax, so a workable definition of “tax” is necessary to give them meaning. The Tax Foundation’s Center for Legal Reform, created in 2005 to advance sensible tax policy in judicial decisions, does just that through filing briefs and efforts to spotlight evasion of constitutional and legislative safeguards.

Today all states except two adhere to a meaningful, taxpayer-protective definition of “tax,” and all states except one have rules requiring that any ambiguity in tax statutes be resolved in the taxpayers’ favor.

Taxes Are Imposed for Revenue Purposes, While Fees Cover the Cost of Providing a Service

Taxes, fees, and penalties are all imposed by government, all raise revenue, and all impose economic costs. While some may equate a tax to any government action that results in costs of any kind, the general public and the courts have been careful to distinguish between different forms of government-collection exactions. The key difference between these different assessments, according to laws and interpretive rules used in nearly every state, is their purpose.

- Taxes are imposed for the primary purpose of raising revenue, with the resultant funds spent on general government services.

- Fees are imposed for the primary purpose of covering the cost of providing a service, with the funds raised directly from those benefitting from a particular provided service.

- Penalties are imposed for the primary purpose of penalizing or regulating behavior, generally imposed as part of judicial proceedings, with resultant revenue a secondary consideration.

- Some taxes, known as Pigouvian taxes, are justified on grounds that they will discourage behavior, but their primary purpose remains revenue raising.

- Revenues from some taxes, known as user taxes, are deposited in a special dedicated fund and not the general fund. If their purpose is revenue generation for general government functions, these are still taxes although they can be mischaracterized as fees.

Therefore, to determine whether a charge is a tax, one must look at its primary purpose. A charge is not a tax if it is not imposed by the government, collected from those receiving particularized benefits to pay for those benefits, or collected for a primary purpose other than raising revenue.

At present, all states except two (North Carolina and Oregon) focus on purpose in distinguishing taxes from other types of revenue. This purpose-based standard is also used internationally, as ratified by the Vienna Convention of 1961 (leading to disputes over diplomats not paying New York parking tickets or U.S. officials refusing to pay the London Congestion Zone charge).

An essential corollary of the purpose standard for defining tax is that the label used by the legislature in framing the tax is not dispositive. Most states have explicitly held that how the charge operates is more important than the label used, with many others silent on the point. Two states (Delaware and North Carolina) are unclear, with cases in both states relying heavily on the label given by the legislature.

Tax Statute Ambiguity Should Be Resolved in Favor of the Taxpayer

In situations where a tax case could be resolved either way, or where a tax statute could have two possible interpretations, all states except one (Oregon) have adopted a rule that such ambiguity is resolved in favor of the taxpayer. This rule is of particular importance when a local government or special district is imposing a tax but does not have proper state permission to do so.

Courts are generally reluctant to suspend the operation of a revenue-raising statute and in some cases are actively prevented from doing so on separation of powers grounds. However, judges will not allow the continued collection of a tax if its basis is improper or even ambiguous.

“Voluntariness” is Immaterial

Some argue that a tax is “compulsory” while a fee is “voluntary,” a test adopted partly by 13 states and rejected explicitly by 10 states and implicitly by many others. The attempt to use this notion to define taxes has proven problematic because it conflates the payment of the charge with the payment of the underlying service.

One may purchase a product “voluntarily,” but this does not make the sales taxA sales tax is levied on retail sales of goods and services and, ideally, should apply to all final consumption with few exemptions. Many governments exempt goods like groceries; base broadening, such as including groceries, could keep rates lower. A sales tax should exempt business-to-business transactions which, when taxed, cause tax pyramiding. paid on the transaction “voluntary.” Use of a toll road is a result of a voluntary decision, but this fact is irrelevant to the question of whether the toll collected is a tax or a fee; it is a fee only if the revenue is used to defray the costs of providing a service to the payer and is not levied to generate revenue for general spending. Taken to its logical extent, the voluntariness rule would mean that all charges collected for government general revenue, other than perhaps a head tax, are in fact not taxes.

Some Words about the “Obamacare” Decision

In June 2012, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, popularly known as Obamacare, on a 5-4 vote. The Court explained that the individual mandate—a requirement to buy health insurance—was a valid exercise of the federal government’s power to tax.

That explanation came as a surprise, with most observers focused on whether the Act was valid under the Constitution’s Commerce Clause. The Tax Foundation was one of the few organizations that filed a brief on the taxing power argument (with our arguments used by the dissenters). On the Court, four justices rejected the Court’s conclusion and four others stated their preference for upholding the mandate under the Commerce Clause, with only Chief Justice John Roberts focused squarely on the taxing power as the basis for upholding the statute.

Roberts’s rationale regarding the charge owed by a taxpayer who refuses to buy health insurance is as follows. Asserting that this charge is either a penalty or a tax, Roberts concluded it was not a penalty because (1) the amount due is not “prohibitory,” with the cost of insurance always larger than the charge owed; (2) no criminal finding of guilt is required; and (3) the IRS is not permitted to use its normal prosecution and penalty methods to collect the charge. Since it was not a penalty, Roberts explained, it was a valid exercise of the taxing power.

Roberts focused much of his argument on that first point, writing that a financially onerous charge (relative to income) is not permissible under the taxing power, while a large charge relative to income is not. The obvious response is that small and large are subjective, a point the Court punted with the statement that they “need not decide here the precise point at which an exaction becomes so punitive that the taxing power does not authorize it.”

Despite popular reference to the Court’s decision as concluding that the mandate “is a tax,” Roberts’s opinion for the Court carefully avoids such a firm statement. Instead, it states that the mandate “looks like a tax,” “may for constitutional purposes be considered a tax,” “may be viewed as a tax,” “may reasonably be characterized as a tax,” and that “Congress had the power to impose [it] under the taxing power.”

This consistent use of cautious terminology suggests that the Court’s purpose is not to overturn its past precedents defining “tax” but rather to determine a narrow space by which the individual mandate could survive as constitutional. The sheer chaos that could emerge from taking the Court’s definition as a definition of “tax”—small charges are taxes and thus must comply with supermajority and voter threshold requirements, while large charges are penalties and may therefore be levied by local governments without restraint—advises against other courts and judges assuming too much about what the NFIB v. Sebelius ruling means for other contexts.

Next Steps

Our new book, How Is the Money Used? Federal and State Cases Distinguishing Taxes and Fees reviews the state of tax-fee definitional standards in each state. We hope that it helps taxpayers identify further opportunities for legal cases and public education efforts.

To read the full book, download the PDF.

Share this article