For the past two years, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) has been debating how to change the taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. treatment of large multinationals so that countries can tax corporate profits not just where their headquarters, employees, and assets are but also where a company’s customers are located. The implications of such a change could be substantial, not just for some U.S.-based companies but for the U.S. Treasury, in that U.S.-based firms would pay a bit less in tax to the IRS and a bit more to foreign governments.

In a departure from the previous administration’s position, which aimed to give U.S. companies a safe harbor from the OECD rules, it has been reported that Treasury now has offered a proposal that would limit these new tax rules to just the 100 largest and most profitable companies. Based on a review of two datasets (the 2020 Forbes Global 2000 and a 2019 OECD dataset on multinational companies) it is apparent that U.S. companies would bear the brunt of new rules under this fresh proposal.

It is not clear if Treasury officials understand how much this proposal could give away the U.S. tax base, or if the strategy is to give away some U.S. tax revenues in exchange for other countries repealing the Digital Services Taxes that have proliferated in recent years. Either way, the stakes for U.S. companies and the U.S. tax baseThe tax base is the total amount of income, property, assets, consumption, transactions, or other economic activity subject to taxation by a tax authority. A narrow tax base is non-neutral and inefficient. A broad tax base reduces tax administration costs and allows more revenue to be raised at lower rates. are high.

If large, successful companies were evenly distributed around the world, then changing where companies are taxed might not mean too much to any one government. But that is not the case. The U.S. is home to many of the largest and most profitable companies in the world, so a tax policy change that would apply to large, successful companies would disproportionately impact U.S.-based companies.

It is a political question, then, as to whether such a policy could be designed to ensure that U.S. companies are not unduly targeted.

The U.S. has been negotiating with other countries in recent years in determining how to identify which multinationals should receive different tax treatment. Some countries want the rules targeted at digital companies, the lion’s share of which are (again) U.S. companies.

Last summer, then-Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin wrote in a letter to the governments of France, Spain, Italy, and the UK that a reform to international tax rules “must not place the financial burdens predominately on the businesses and the fiscal interests of a single country or industry.”

The policies now being discussed would change tax rules mainly for super-profits of companies, potentially profits above a 10 percent margin. In a report released in 2019, economists at the IMF found that between one-third and one-half of global super-profits are from U.S.-headquartered companies.

It should be unsurprising, then, that the recent proposal from the Biden administration targeting the 100 largest and most profitable companies would disproportionately impact U.S. businesses.

The Forbes Global 2000 list includes the world’s largest public companies. Not all are multinationals, however. This is where the OECD dataset on multinationals comes in. It includes 500 large multinationals and has a measure of how many subsidiaries a company has in foreign jurisdictions. Limiting the Forbes Global 2000 list just to companies in the OECD data and then further limiting the list to companies that have more than 25 percent of their affiliates in foreign jurisdictions results in a list of 353 companies.

Of the top 100 most profitable companies in that list, 52 have their headquarters in the United States, representing 63 percent of the profits of the 100 most profitable companies.

The reporting on the U.S. proposal suggested that there might be industry exclusions from the new rules. In months prior to the new proposal, it had been suggested that financial services and mining industries might be excluded from the rules change.

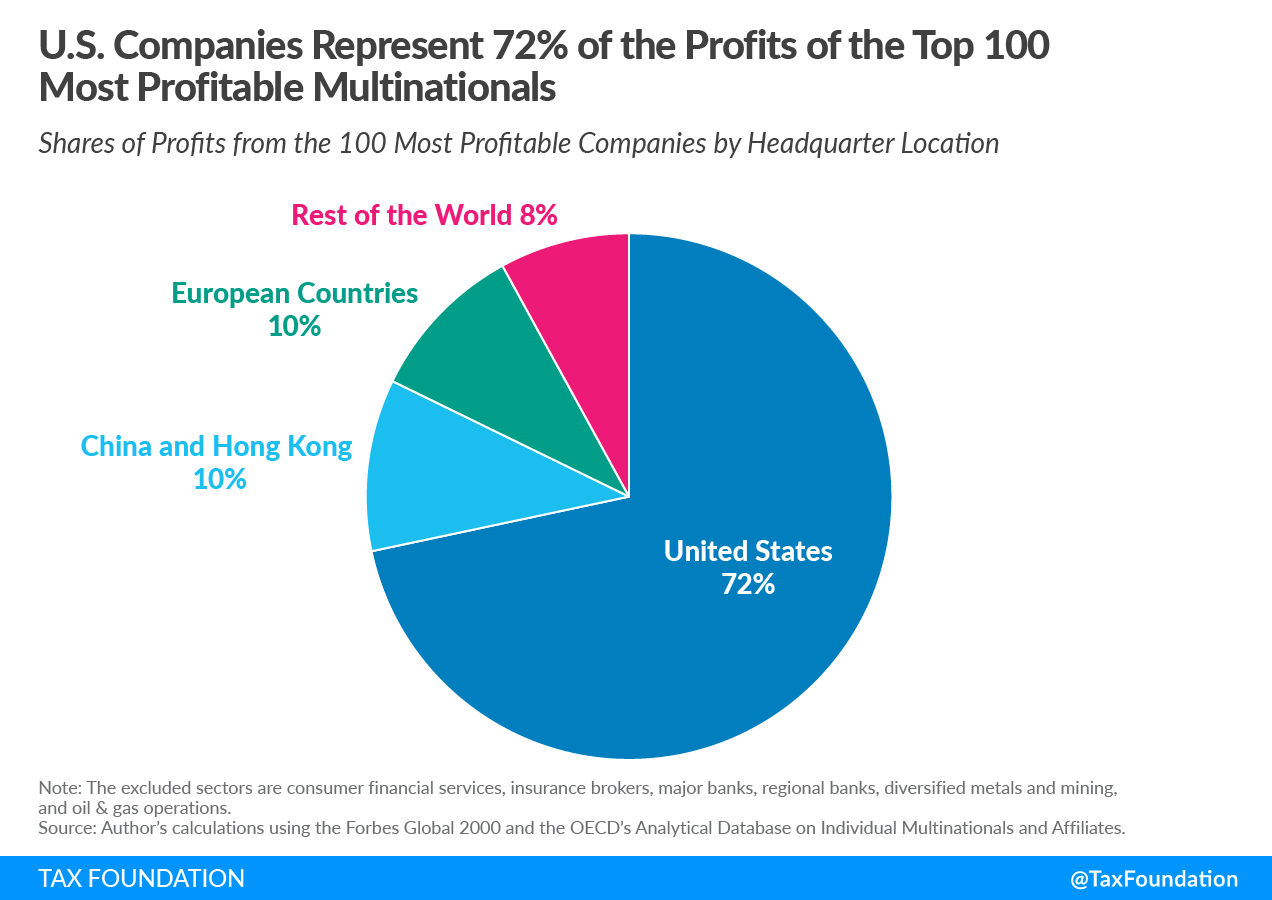

If the list of 353 companies were trimmed to exclude several sectors related to financial services and mining, the list would be shortened to just 285 companies. Among the top 100 most profitable companies in that list, 54 are U.S. companies representing 72 percent of the profits among the top 100.

| Number of U.S. Companies | Share of Profits from U.S. Companies | Average Sales (in Billions) | Average Profit Margin | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Industries | 52 | 63% | $30.93 | 31% |

| All Industries excluding financial services and extractives (see table note) | 54 | 72% | $23.85 | 29% |

|

Note: The excluded sectors are consumer financial services, insurance brokers, major banks, regional banks, diversified metals and mining, and oil & gas operations. Sources: Author’s calculations using the Forbes Global 2000 and the OECD’s Analytical Database on Individual Multinationals and Affiliates. |

||||

While the exact policy rules that would determine which companies will be subject to the new rules are not yet set, U.S. companies would be the main targets of the proposal.

The policy behind this is extremely complex and would have significant compliance and administrative costs. It would mix current rules for taxation with another layer of rules without clear principles behind the approach other than to have separate rules for the largest and most successful companies.

A proposal that is not limited just to the 100 largest companies would lead to more companies in other countries bearing more of the burden, but the overall picture would still be one of countries splitting the riches of successful U.S. businesses.

What would the U.S. get out of this, then? One theme throughout the negotiations has been whether countries would abandon policies like digital services taxes that discriminate against U.S. companies. If other countries agree to what the U.S. is offering, then a condition for agreement will be the removal of those discriminatory policies.

One value of the safe harbor offered by former Secretary Mnuchin was to suggest that the new rules should be enough of an improvement over current policies so U.S. businesses would have an incentive to opt into the new system. This would put pressure on countries to design the new rules with sufficient clarity and simplicity. If the new rules were as bad or worse for tax certainty and compliance, then the safe harbor would apply, and companies could continue to be taxed under existing rules.

Current Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen removed the safe harbor from the U.S. negotiating position and has now proposed limiting the scope of the rules in such a way that U.S. companies would likely make up the majority of businesses facing the new rules.

As mentioned, new international tax rules on super-profits would disproportionately impact U.S. companies however they are designed. The question that Treasury should answer is why limit the policy in such a way that magnifies that disproportionate application and the risk to the U.S. tax base.

Launch Resource Center: President Biden’s Tax Proposals

Share this article