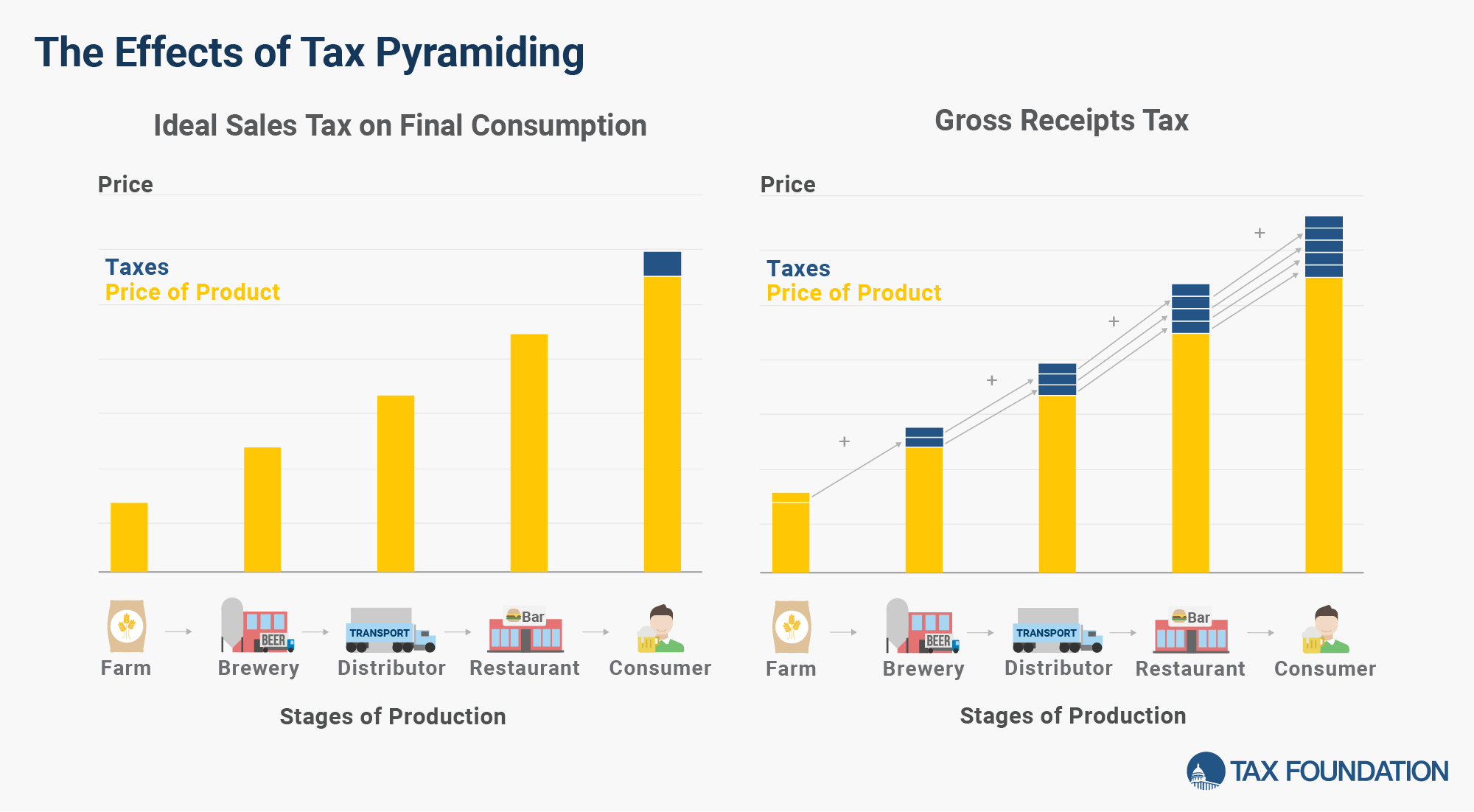

Gross receipts taxes are applied to a company’s gross sales, without deductions for a firm’s business expenses, like compensation, costs of goods sold, and overhead costs. Unlike a sales tax, a gross receipts tax is assessed on businesses and applies to transactions at every stage of the production process, leading to tax pyramiding.

History of Gross Receipts Taxes

Gross receipts taxes (GRTs), also historically called “turnover taxes,” have a long history, and were a regular feature of the tax systems of the ancient world. Their chief advantage was simplicity in an era before modern accounting or the state capacity to impose more granular taxes on a wider range of taxpayers. A high-rate gross receipts tax, Spain’s alcabala (or alcavala), remains well-known today in large part due to Adam Smith’s evisceration of the tax in Wealth of Nations, blaming it, with good reason, as a major contributor to Spain’s economic decline. Over time, these taxes fell out of favor as their deleterious effects became more apparent and tax systems grew in sophistication. However, they never quite went extinct, with several US states currently imposing GRTs or permitting localities to do so. They occasionally receive new interest from lawmakers due to their significant revenue potential as taxes on an excessively broad base.

A number of states tinkered with gross receipts taxes in the first century and a half of the nation’s history, but the first GRT to emerge as a sustained and significant source of revenue was West Virginia’s Business & Occupation (B&O) tax, implemented in 1921. These taxes spread during the 1930s, as the Great Depression reduced state property and income tax revenue. By the late 1970s, however, these taxes began to be repealed or struck down as unconstitutional by state courts.

Nevertheless, gross receipts taxes have returned as a revenue option for policymakers after being dismissed for decades as inefficient and unsound tax policy. Their appeal comes as many states are looking to replace revenue lost by eroding corporate income tax bases and as a way to limit revenue volatility. Nearly all states use gross receipts as a tax base in some contexts, most commonly for utility and energy companies. These limited taxes, however, should be distinguished from what is typically meant by gross receipts taxes, as they often function much more like ad valorem excise taxes on specific industries or activities, with limited potential for harmful tax pyramiding.

The Effects of Gross Receipts Taxes

Because GRTs are imposed at intermediate stages of production and do not allow (or strictly limit) deductions for costs, they are not based on profits or net income, like a corporate income tax, or final consumption, like a well-constructed sales tax. They provide an advantage to businesses with high profit margins or considerable vertical integration, while they penalize companies with narrow margins or multiple transacted stages of production. This distorts economic decision-making, incentivizing firms to vertically integrate, adjust production to gain a more favorable industry classification, or move stages of production outside the taxing jurisdiction. This introduces inefficiency, to the extent that businesses make economic decisions hinging on tax planning and avoidance strategies, and inequity, to the extent that businesses are unable to respond in this manner.

The adverse effects of having to pay these taxes can be particularly severe for startups that post losses in early years, and for businesses with low margins or periods of unprofitability. To the extent that most or all businesses in a given market are subject to these taxes, much of the pyramiding tax costs are ultimately passed along to consumers, who face high, hidden, and nonneutral taxation on the purchased final product. When only certain businesses or industries face such taxation, however, and consumers are able to purchase similar products by unaffected companies, gross receipts taxes can severely cut into affected businesses’ profit margins or even render them unprofitable and unable to compete.

Stay updated on the latest educational resources.

Level-up your tax knowledge with free educational resources—primers, glossary terms, videos, and more—delivered monthly.

Subscribe