Chairman Hatch, Ranking Member Wyden, members of the Committee, I commend you for taking on the challenge of reforming America’s tax code and especially the task of overhauling our outdated business taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. system.

The most important thing that Congress and the administration can do to boost economic growth, lift workers’ wages, create jobs, and make the U.S. economy more competitive globally, is reform our business tax system.

I’d like to focus my remarks on reforming the corporate tax system. The tax issues facing pass-through businesses could fill an entire hearing itself. The Tax Foundation generally supports the idea of corporate integration, so perhaps we can address the pass-through sector during questions.

My testimony will first outline the policies that our research indicates will maximize economic growth and boost wages, what we call “The Four Pillars of Corporate Tax Reform.” I will then address the challenges that you will face in crafting a successful tax reform plan—balancing the math with the economics.

The Four Pillars of Corporate Tax Reform

The Tax Foundation’s extensive economic research and tax modeling experience suggests that the committee should have four priorities in mind when reforming the corporate tax system:

- Providing full expensingFull expensing allows businesses to immediately deduct the full cost of certain investments in new or improved technology, equipment, or buildings. It alleviates a bias in the tax code and incentivizes companies to invest more, which, in the long run, raises worker productivity, boosts wages, and creates more jobs. for capital investments;

- Cutting the corporate tax rate to a globally competitive level, such as 20 percent;

- Moving to a competitive territorial tax systemTerritorial taxation is a system that excludes foreign earnings from a country’s domestic tax base. This is common throughout the world and is the opposite of worldwide taxation, where foreign earnings are included in the domestic tax base. ; and

- Making all three of these policies permanent.

While many of you, and certainly many in the business community, may see some of these policies as competing for space in a tax plan, we see those pieces as complementary and essential, not in conflict.

In our view, cutting the corporate tax rate and moving to a territorial system are essential for restoring U.S. competitiveness and reducing the incentive for profit-shifting and corporate inversions. Expensing, we believe, is key to reducing the cost of capital in order to revitalize U.S. capital investment which, in turn, will boost productivity and wages.

Thus, a good tax plan should include all three of these policies because they will not only boost economic growth, but do so in a way that leads to higher wages and living standards for working Americans. However, these gains are not possible if the policies are made temporary, as some have suggested as a way of minimizing their revenue loss or complying with the Byrd Rule. Temporary tax cuts deliver temporary economic results; permanent tax reform delivers permanent economic benefits.

The Economic Benefits of Expensing and a Corporate Rate Cut

Let’s look at the economics of expensing and the corporate rate cut in more detail. Both policies are very pro-growth and will ultimately lift workers’ wages. But, on a dollar-for-dollar basis, expensing delivers twice the economic growth as a corporate rate cut.[1]

The reason it does so is because expensing of new investment is focused on cutting the cost of growing the capital stock, while the rate reduction’s benefits are spread over returns to existing capital and to other activities such as research, management, advertising, and other inputs that are already immediately deductible.

For example, if I own a factory that makes appliances, a lower corporate rate will increase the amount of after-tax profit I earn on each toaster, but it will not necessarily incentivize me to produce more toasters. On the other hand, the only way that I can reap the benefits of full expensing is by adding a new toaster assembly line or building a factory. Thus, the corporate rate cut initially flows to my bottom line, whereas the new capital investment immediately benefits my workers and new employees.

The Combined Benefits of Expensing and a Corporate Rate Cut

The House GOP “Better Way” Tax Reform Blueprint combined expensing with a 20 percent corporate rate. Our scoring of the plan indicated that these policies created a powerful engine for economic growth and lifting after-tax incomes.[2] They should provide the core of any pro-growth tax reform plan.

We used our Taxes and Growth (TAG) Macroeconomic Tax Model[3] to simulate the long-term economic effects of these policies separately and combined to give you an idea of how they work together. The table below summarizes the long-term results of this exercise.

Here we can see that cutting the corporate tax rate to 20 percent and moving to full expensing for corporations each boost the long-term level of GDP by 3 percent and increase the capital stock by more than 8 percent. This has the effect of lifting wages by more than 2.5 percent and creating more than 575,000 full-time equivalent jobs. In this example, long term is generally about ten years, once the policies have worked their way through the economy.[4]

Combining the two policies does not double the results because of their interactive effects. However, we can see that the two policies together would increase the level of GDP by 4.5 percent and the capital stock by nearly 13 percent. These economic forces act to lift wages by an average of 3.8 percent and create 861,000 full-time equivalent jobs.

| 20% Corporate Tax Rate | Corporate Only Full Expensing | 20% Rate and Full Expensing Combined | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tax Foundation, Taxes and Growth Model | |||

| GDP, long-run change in annual level (percent) | 3.1% | 3.0% | 4.5% |

| GDP, long-run change in annual level (billions of 2016 $) | $587 | $571 | $867 |

| Private business stocks (equipment, structures, etc.) | 8.5% | 8.3% | 12.8% |

| Wage Rate | 2.6% | 2.5% | 3.8% |

| Full-time Equivalent Jobs (in thousands) | 592 | 575 | 861 |

Both Policies Boost After-Tax Incomes Substantially

There is typically little public support for corporate tax reform because most people don’t see how it will benefit their lives. Corporate tax reform may not “put cash in people’s pockets” in the same way as a cut in individual tax rates, but it can have a powerful effect on lifting after-tax incomes and living standards.

As we saw in the modeling results above, both expensing and a corporate rate cut can boost wages because of the increased productivity generated by the growth in capital investment. Better tools make workers more productive. Workers who are more productive earn more over time. When these gains are combined with the overall growth in the economy, after-tax incomes and living standards will rise.

Tax Foundation’s TAG model factors these macroeconomic effects into our estimates of the change in after-tax incomes for taxpayers at different income levels. The nearby table shows that a 20 percent corporate tax rate would lift after-tax incomes by an average of 3.5 percent. The TAG model estimates that the combination of the 20 percent corporate tax rate and full expensing would boost after-tax incomes by an average of 5.2 percent. Again, these gains represent the combination of wage growth, economic growth, and the distributed dollar value of the tax cuts.

| Tax Foundation, Taxes and Growth Model | |||

| Income Group | 20% Corporate Tax Rate | Corporate Only Full Expensing | 20% Rate and Full Expensing Combined |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0% to 20% | 3.5% | 3.4% | 5.2% |

| 20% to 40% | 3.3% | 3.2% | 4.8% |

| 40% to 60% | 3.4% | 3.3% | 5.0% |

| 60% to 80% | 3.4% | 3.3% | 5.0% |

| 80% to 100% | 3.6% | 3.5% | 5.3% |

| 80% to 90% | 3.4% | 3.3% | 5.1% |

| 90% to 95% | 3.5% | 3.4% | 5.2% |

| 95% to 99% | 3.6% | 3.5% | 5.4% |

| 99% to 100% | 3.7% | 3.6% | 5.5% |

| TOTAL | 3.5% | 3.4% | 5.2% |

Cutting the Corporate Tax Rate Will Immediately Improve U.S. Competitiveness

It is well-known that the 35 percent U.S. federal corporate tax rate is the highest among the 35 member nations in the OECD. However, U.S. firms also pay state income taxes. When the average state rate is added to the federal rate, American companies face an average U.S. rate of 38.91 percent tax on corporate earnings.

In a recent study, Tax Foundation economists compared the corporate tax rates levied by 202 jurisdictions across the globe and found that the United States has the fourth highest statutory corporate income taxA corporate income tax (CIT) is levied by federal and state governments on business profits. Many companies are not subject to the CIT because they are taxed as pass-through businesses, with income reportable under the individual income tax. rate in the world. [5] The only jurisdictions with a higher statutory rate are the U.S. territory Puerto Rico (with a population of 3.7 million), the United Arab Emirates (population 9.4 million), and the tiny African island nation of Comoros (population 826,000).

From a tax perspective, most other countries are much more competitive than the U.S. The worldwide average statutory corporate income tax rate, measured across 202 tax jurisdictions, is 22.96 percent. When weighted by GDP, the average statutory rate is 29.41 percent—ten points lower than the U.S. statutory rate.

Our major trading partners in Europe have the lowest regional average rate, at 18.35 percent (25.58 percent when weighted by GDP). Conversely, among our major trading partners, Africa and South America tie for the highest regional average statutory rate at 28.73 percent (28.2 percent weighted by GDP for Africa, 32.98 percent weighted by GDP for South America).

While we frequently hear the excuse that “nobody really pays the headline rate” because of loopholes in the tax code, the fact is, the tax codes in other countries also have loopholes. This means that the effective corporate tax rate in those countries is typically well below our effective rate.

Indeed, a recent Tax Foundation study compared the tax burden on new investment, the marginal effective tax rate (METR), among 43 nations. After accounting for all the various deductions and credits in each tax code, the study finds that the METR in the U.S. is the fifth highest among the 43 nations at 34.8 percent.[6] Were it not for bonus depreciation, our ranking would be even higher.

Lowering the corporate tax rate to at least 20 percent would instantly make the U.S. more competitive while reducing the incentives for profit-shifting and inversions.

Moving to a Territorial Tax System is Imperative

One of the most challenging issues facing lawmakers is over the international aspects of tax reform: designing a territorial tax system and crafting the rules that determine when the foreign income of U.S. multinationals will be taxed and when it will be exempt from U.S. tax.

These rules are extremely complex and the stakes are very high. Tax writers must design rules that protect the U.S. tax baseThe tax base is the total amount of income, property, assets, consumption, transactions, or other economic activity subject to taxation by a tax authority. A narrow tax base is non-neutral and inefficient. A broad tax base reduces tax administration costs and allows more revenue to be raised at lower rates. and prevent tax avoidance, yet do so in a manner that is not burdensome and does not stifle capital flows and legitimate business transactions. The wrong choices could make U.S. firms even less competitive globally than they are today.[7]

The interesting aspect of this issue is that the U.S. already has a territorial tax system—but it only applies to foreign-owned companies. Foreign-owned companies only pay U.S. income taxes on their U.S. profits and, naturally, pay no U.S. tax on their foreign profits. This situation automatically makes U.S. firms less competitive in foreign markets. The only way to level the playing field is for lawmakers to repeal our worldwide tax system and move to a territorial system for all companies.

Expensing Saves More than $23 Billion in Compliance Costs

One last thing to consider about expensing. A move to full expensing accomplishes something that no rate cut can: it eliminates pages from the tax code, thus saving taxpayers time and money. American businesses today spend more than 448 million hours each year complying with the Byzantine depreciationDepreciation is a measurement of the “useful life” of a business asset, such as machinery or a factory, to determine the multiyear period over which the cost of that asset can be deducted from taxable income. Instead of allowing businesses to deduct the cost of investments immediately (i.e., full expensing), depreciation requires deductions to be taken over time, reducing their value and discouraging investment. and amortization schedules, at an estimated cost of over $23 billion annually. Moving to full expensing eliminates the need for these complicated schedules, thus saving businesses the $23 billion in compliances costs, which is an added benefit to the impact the policy has on boosting wages and economic growth.[8]

Temporary Tax Cuts Produce [No Surprise] Temporary Economic Benefits

Because of the procedural limitations associated with the Senate’s Byrd Rule, some lawmakers have talked about the merits of a temporary tax cut plan, which would sunset after ten years, much like the tax cuts enacted by President George W. Bush in 2001 and 2003.

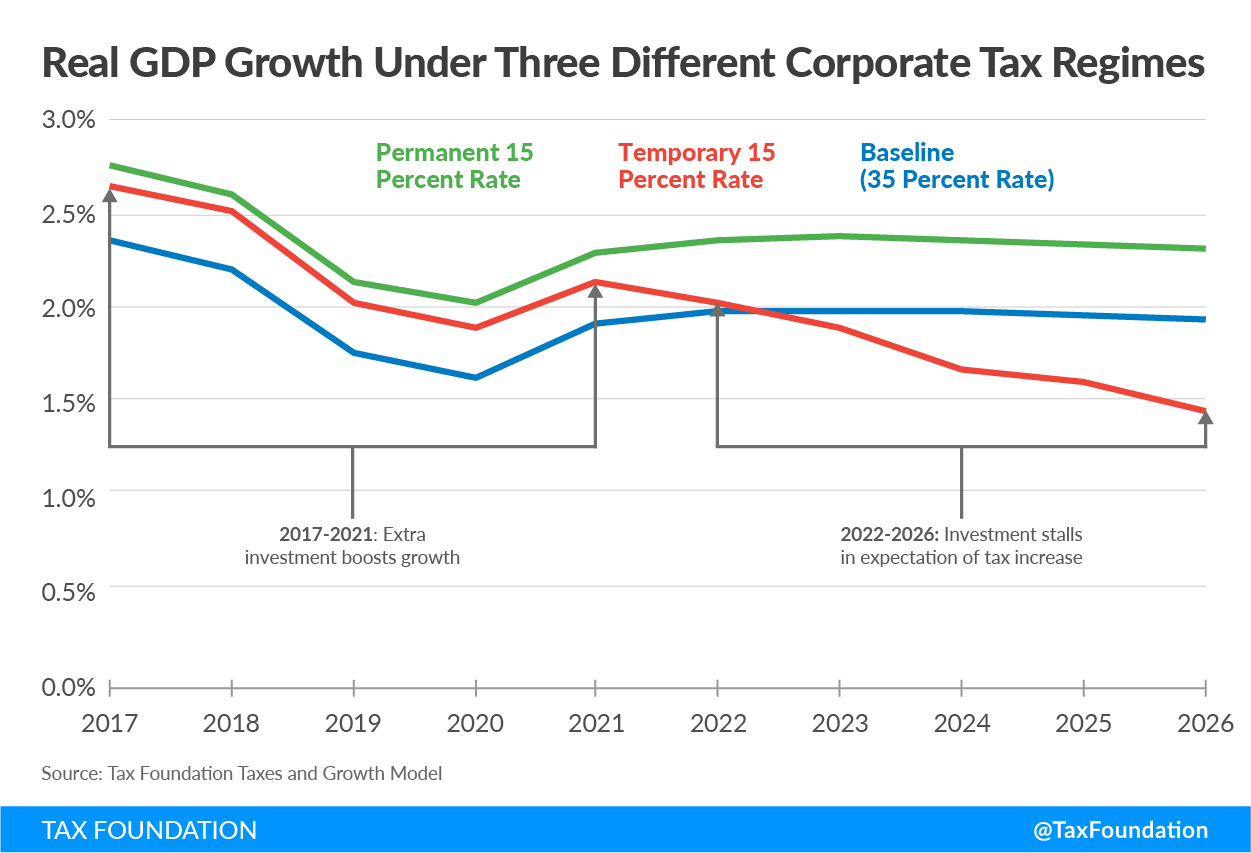

Tax Foundation economists used the TAG model to simulate the effects of a temporary corporate rate cut to 15 percent compared to the effects of a permanent rate cut, and the baseline estimates under current law. The results are shown in the nearby chart.[9]

A permanent corporate rate reduction reduces the cost of capital and makes new investments worthwhile that otherwise would not have been. Under the TAG model, a permanent cut to 15 percent boosts investment substantially, which allows a sustained period of higher growth. Such a policy adds about 0.39 percentage points to GDP growth per year over a decade, eventually resulting in a GDP that is 3.9 percent larger than the baseline scenario after ten years. This additional 3.9 percent level adjustment to GDP remains for as long as the policy stays in effect; more investments are profitable, and therefore, the nation is richer.

A temporary corporate rate reduction looks similar at first: it initially produces more investment and growth. However, the effect is never as strong as for the permanent cut. Worse, the improvements to growth fade considerably. The increase in GDP peaks in the sixth year, with a grand total of 1.37 percent added to GDP over all six years. Then, growth from the seventh year on is actually slower than it would have been with no tax cut at all. By the end of the tenth year and the sunset of the policy, GDP is only 0.14 percent larger than it would have been without the tax cut.

The lesson is very clear: the only way to boost the economy for the long term is to make the business tax reforms permanent.

The Challenges and Trade-offs of Business Tax Reform

The great economist Thomas Sowell once said that “there are no solutions, there are only trade-offs.” As I’m sure you are already discovering, you will face some big challenges in fixing the corporate tax system. First, the math is hard. There are not as many “loopholes” in the corporate tax code as many people believe, so you will likely have to think outside the box if you want corporate tax reform to be revenue neutral. Second, the economics of tax reform must be at the forefront of your decision-making. If you make the wrong choice in the base broadeners you use to offset the tax cuts, you can neutralize all the benefits you hope to achieve from the reforms. These challenges will require hard decisions and considerable trade-offs.

The Math is Hard

Cutting the corporate tax rate to 20 percent and providing full expensing could reduce federal revenues by as much as $3 trillion over ten years on a static basis. While our models show that the growth effects of the policies could recover as much as 46 percent of this revenue loss over a decade (and more beyond the budget window), finding the revenue offsets to make these policies revenue neutral will be a major challenge.

For example, if your goal is to eliminate corporate tax expenditures to offset a rate cut, your options are limited. By our estimates, there are only enough “loopholes,” or nonstructural items, to eliminate in the corporate tax code to bring the rate down to about 28.5 percent.[10] If the consensus is to lower the rate to 20 percent, or even 15 percent as President Trump advocates, you will have to find offsets outside the corporate tax base.

One of the larger offsets included in the House GOP Blueprint was the elimination of the net interest deduction for corporations. This policy has the advantage of raising more than $1 trillion with minimal impact on economic growth. Moreover, it also equalizes the treatment of debt and equity financing, thus reducing the amount of leveraging in the economy.

Aside from the elimination of net interest and the controversial border adjustment proposal, there are very few politically palatable revenue raisers or base broadeners available that can be used to help reduce the corporate tax rate to 20 percent or below. A few of the options that could raise more than $1 trillion over ten years include a $20 per-ton carbon taxA carbon tax is levied on the carbon content of fossil fuels. The term can also refer to taxing other types of greenhouse gas emissions, such as methane. A carbon tax puts a price on those emissions to encourage consumers, businesses, and governments to produce less of them. , removing the Social Security Payroll taxA payroll tax is a tax paid on the wages and salaries of employees to finance social insurance programs like Social Security, Medicare, and unemployment insurance. Payroll taxes are social insurance taxes that comprise 24.8 percent of combined federal, state, and local government revenue, the second largest source of that combined tax revenue. cap, and enacting a value-added tax (VAT).[11]

On the other hand, there are ways of reducing the cost of these proposals by either phasing them in or modifying them. For example, the cost of full expensing could be reduced substantially through the use of neutral cost recoveryCost recovery refers to how the tax system permits businesses to recover the cost of investments through depreciation or amortization. Depreciation and amortization deductions affect taxable income, effective tax rates, and investment decisions. . This option maintains current depreciation schedules, but indexes them for inflation and a modest rate of return. This modification gives taxpayers the net present value equivalent of full expensing, but spreads the budgetary costs over time.

Congress could also follow the example of other countries, such as Canada and the United Kingdom, who ratcheted down their corporate tax rate over a number of years. This option would reduce the cost of the policy within the ten-year budget window, but not during the second ten years.

Getting the Economics Right

In order to maximize the benefits of corporate tax reform you must be very careful in choosing the offsets you need to make the plan revenue neutral. You must avoid base broadeners that raise the cost of capital because they will neutralize the benefits of the pro-growth tax reforms.

A good example of how the wrong mix of policies can neutralize a plan’s economic growth potential is the draft tax reform plan proposed by former Ways and Means Chairman Dave Camp. The so-called Camp Draft cut the corporate tax rate to 25 percent, but largely offset the revenue loss by lengthening depreciation lives—moving from the current MACRS to ADS, the alternative depreciation system.

As the tax models used by the Joint Committee on Taxation and the Tax Foundation showed, the longer depreciation lives raised the cost of capital to such an extent that it largely negated the economic benefits of the lower corporate tax rate.[12] Revenue neutrality may be an important goal, but it should not be achieved at the expense of economic growth. That is self-defeating. To fully reach the goal of a lower corporate tax rate, you may have to relax the standard for revenue neutrality.

One of the reasons that the House GOP “Better Way” Tax Reform Blueprint contained the controversial border adjustment was the recognition by its designers of the need to reach outside the traditional corporate tax expenditure base to find the necessary revenues to lower the corporate tax rate to 20 percent. The border adjustment also had a minimal impact on economic growth. Thus it raised more than $1 trillion over a decade in offsetting revenues while maximizing the economic benefits of the lower corporate tax rate and full expensing proposals.

Conclusion

Mr. Chairman, corporate tax reform done right is key to growing the economy, boosting real family incomes, and making the U.S. a better place to do business in, and do business from. The Four Pillars of Corporate Tax Reform—full expensing, a lower corporate tax rate, a territorial system, and permanence—are the right policies to make this tax reform effort a lasting success.

Thank you. I’m happy to answer any questions you may have.

[1] For an excellent discussion of this issue, see Kyle Pomerleau, “Why Full Expensing Encourages More Investment than a Corporate Rate Cut,” Tax Foundation Blog, May 3, 2017. https://taxfoundation.org/full-expensing-corporate-rate-investment/.

[2] Kyle Pomerleau, “Details and Analysis of the 2016 House Republican Tax Reform Plan,” Tax Foundation Fiscal Fact No. 516, July 5, 2016.

[3] For a full description of the TAG model, see https://taxfoundation.org/federal-tax/taxes-and-growth-model-overview-methodology/. We are also happy to give live demonstrations of the model upon request.

[4] Over the long term, a 20 percent corporate rate is a bigger tax cut than expensing. That is why we are seeing comparable results from the policies.

[5] Kyle Pomerleau and Keri Jahnsen, “Corporate Income Tax Rate Around the World,” Tax Foundation Fiscal Fact 559, September 7, 2017. https://taxfoundation.org/corporate-income-tax-rates-around-the-world-2017/.

[6] Jack Mintz and Philip Bazel, “Competitiveness Impact of Tax Reform for the United States,” Tax Foundation Fiscal Fact 546, April 20, 2017.

[7] Kyle Pomerleau and Keri Jahnsen, “Designing a Territorial Tax System: A Review of OECD Systems,” Tax Foundation Fiscal Fact No. 554, August 1, 2017.

[8] Scott A. Hodge, “The Compliance Costs of IRS Regulations,” Tax Foundation Fiscal Fact No. 512, June 15, 2016.

[9] Alan Cole, “Why Temporary Corporate Income Tax Cuts Won’t Generate Much Growth,” Tax Foundation Fiscal Fact No. 549, June 2017.

[10] Scott Greenberg, “To Lower the Corporate Tax Rate, Lawmakers Will Have to Think Outside the Box,” Tax Foundation Blog, June 8, 2017. https://taxfoundation.org/lower-corporate-tax-rate-think-outside-box/.

[11] For a menu of options, see Options for Reforming America’s Tax Code, Tax Foundation, 2016. https://taxfoundation.org/options-reforming-americas-tax-code/

[12] Stephen J. Entin, Michael Schuyler, William McBride, “An Economic Analysis of the Camp Tax Reform Discussion Draft,” Tax Foundation Special Report No. 219, May 14, 2014.