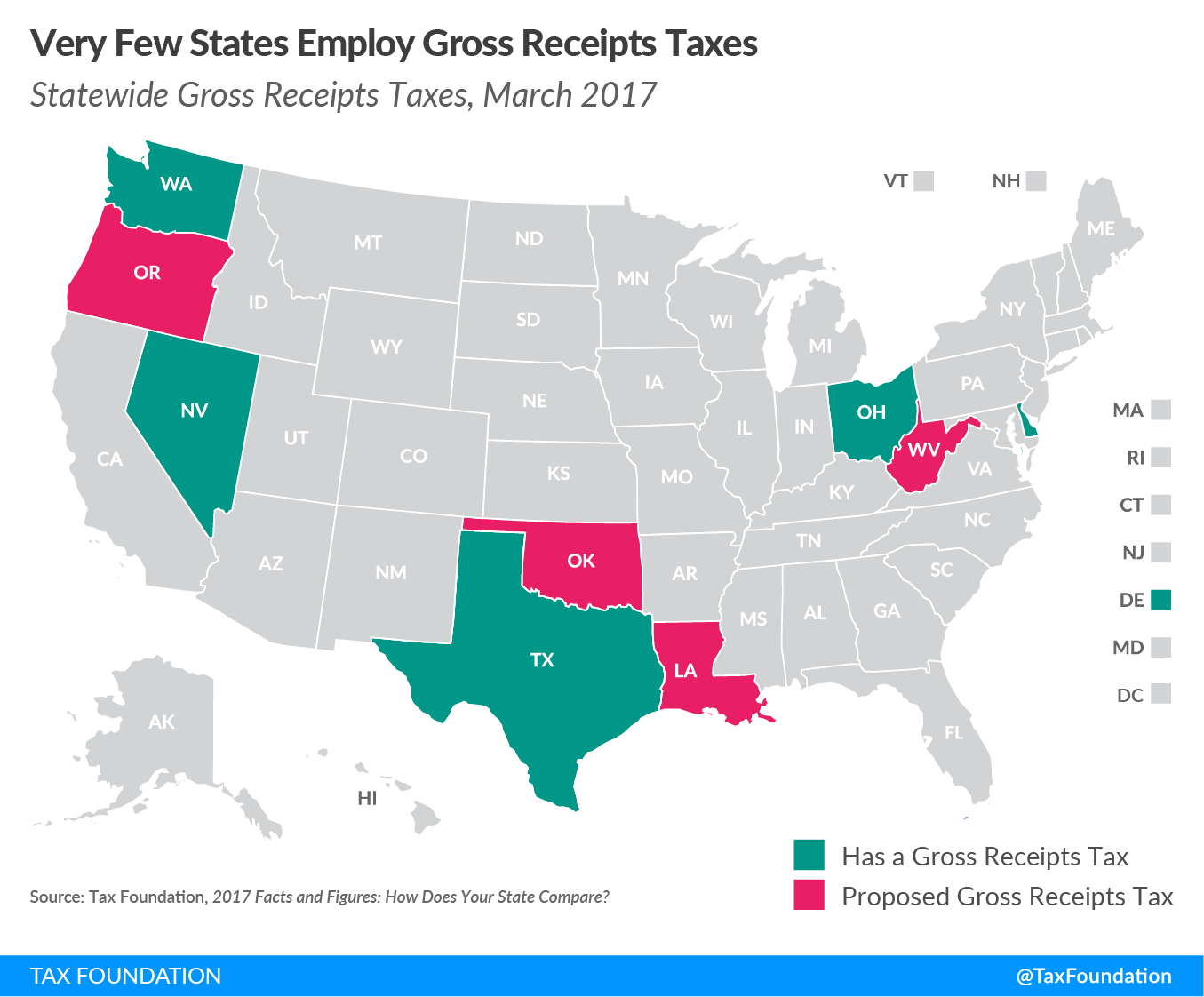

Gross receipts taxes are rarely used by states. Only five states, Delaware, Nevada, Ohio, Texas, and Washington, have statewide gross receipts taxGross receipts taxes are applied to a company’s gross sales, without deductions for a firm’s business expenses, like compensation, costs of goods sold, and overhead costs. Unlike a sales tax, a gross receipts tax is assessed on businesses and applies to transactions at every stage of the production process, leading to tax pyramiding. (see map below). However, a number of states could be joining to help close budget gaps–this is the wrong approach for states.

The majority of states repealed their gross receipts taxes in the 1920s and 1930s and replaced them with retail sales taxes, but in the last two years, states have begun to reinvestigate gross receipts taxes. In 2015, Nevada created its Commerce TaxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. , after a gross receipts tax failed on the ballot in 2014. In 2016, Oregon voters considered Measure 97, which would have established a gross receipts tax of 2.5 percent on all sales in excess of $25 million. While Measure 97 was defeated by 19 points, Oregon continues to explore possible gross receipts taxes.

And now this pace is accelerating. Four states, Louisiana, Oklahoma, Oregon, and West Virginia, so far in 2017 have considered gross receipts tax proposals. (Louisiana Governor Edwards is expected to release details as early as Wednesday.) More could be coming too.

This trend is concerning. The flaws of gross receipts taxes are well documented. Gross receipts taxes lead to higher consumer prices, lower wages, and fewer job opportunities, as the tax pyramids throughout the production cycle. Unlike a retail sales taxA sales tax is levied on retail sales of goods and services and, ideally, should apply to all final consumption with few exemptions. Many governments exempt goods like groceries; base broadening, such as including groceries, could keep rates lower. A sales tax should exempt business-to-business transactions which, when taxed, cause tax pyramiding. that is assessed only on the final consumer purchase of a product, a gross receipts tax is assessed at every stage of production. (Many retail sales taxes do not fully exempt business inputs, and do have a small, but notable, amount of pyramiding.)

Why are states considering a gross receipts tax, given the noted flaws? Gross receipts taxes have two main benefits: They produce large and stable amounts of revenue. Gross receipts tax bases are wider than the entire economy, generating revenue quickly. The same product is taxed multiple times as it moves to the market. And, since gross receipts taxes are assessed on sales, not income, they are not as volatile. They are less impacted by the ebbs and flows of the business cycle as business income varies year-to-year. Under a corporate income taxA corporate income tax (CIT) is levied by federal and state governments on business profits. Many companies are not subject to the CIT because they are taxed as pass-through businesses, with income reportable under the individual income tax. , firms do not pay the tax if their profits are zero or negative. The same is not true of a gross receipts tax.

But these two reasons are not sufficient for adding a gross receipts tax to a state’s tax code. If a state is looking for stability, there are many other options to consider, such as a properly structured sales tax. If a state is looking for new revenue, there are ways to expand current tax bases to produce new revenue.

States have been down this road before. In the mid-2000s, several states explored adding gross receipts taxes. Michigan, New Jersey, and Kentucky added gross receipts taxes, but quickly repealed them due to their economic consequences. (Ohio and Texas created their gross receipts taxes at the same time, which still exist.) At the same time, Indiana repealed its decades-old gross receipts tax. As my coauthor, Erica Wilt, and I wrote last year:

The experience in all four states reveals how gross receipts taxes have a negative impact on the economy. Indiana demonstrates how gross receipts taxes are outmoded, can tax different industries at varying effective rates, and discourage business; New Jersey demonstrates how disproportionate and arbitrary the tax can be, which places an unfair burden on businesses; Kentucky’s tax shows how some businesses are placed at a disadvantage compared to others and that investment levels dampen; and Michigan provides evidence that gross receipts taxes add layers of tax complexity that decrease competitiveness.

These state experience are not the exception, but rather the norm.

Sadly, a number of states are poised to repeat the folly of their peers, with the resurgence of gross receipts taxes. Largely resigned to the tax trash heap of history, gross receipts taxes are currently being considered as part of tax plans in four states. Hopefully, these states, and others, realize instituting a gross receipts tax is the wrong approach.

For more information on gross receipts taxes, click here.

Share this article