Key Findings

- Under current law, the taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. code exempts credit unions from paying corporate income taxes. The Joint Committee on Taxation estimates the exemption will reduce federal revenue by $1.9 billion in 2019.

- Historically, the exemption was justified on the grounds that credit unions would fulfill three purposes: restrict their customer base to people with a common bond, serve customers of moderate means, and provide services that were difficult to obtain at banks.

- Evidence indicates that the credit union industry has strayed from its original, tax-exempt purpose and is in direct competition with its taxed competitors.

- The exemption cannot be justified on the grounds of sound tax policy, is not neutral, and leads to an inefficient allocation of resources.

- Ending the exemption would make the tax code more efficient and provide lawmakers with revenue that could be used to offset the cost of other improvements in the tax code.

Introduction

Under current law, the federal tax code exempts credit unions from corporate income taxes. Credit unions were granted their tax exemption with the understanding they would provide financial services that were unavailable or difficult to obtain elsewhere to lower-income, unbanked individuals with a strong common bond.

However, evidence indicates that credit unions have evolved since their exemption was granted and now closely resemble other financial institutions that are subject to the corporate income tax. The exemption for credit unions is not justifiable on the grounds of sound tax policy.

This paper reviews the history of the exemption, the arguments made for its existence, and the extent to which credit unions fulfill their tax-exempt purpose today and finds that the exemption for credit unions should be repealed.

Overview of the Exemption

Credit unions are nonprofit financial cooperatives that accept deposits, make loans, and offer other types of financial services to their members. Federal chartering of credit unions began in the midst of the Great Depression with the Federal Credit Union Act of 1934. Prior to this, many states had passed laws allowing for state-chartered credit unions.

Today, both state-chartered[1] and federal credit unions are exempt from the federal corporate income taxA corporate income tax (CIT) is levied by federal and state governments on business profits. Many companies are not subject to the CIT because they are taxed as pass-through businesses, with income reportable under the individual income tax. , while federal credit unions are also exempt from state-level taxes except for real and tangible personal property taxes.[2] The state-chartered exemption dates to 1917 and the federal to 1937. In 1951, Congress revoked the tax-exempt status of some types of financial institutions, while specifically granting it for state-chartered credit unions.[3]

The Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) estimates that the federal tax exemptionA tax exemption excludes certain income, revenue, or even taxpayers from tax altogether. For example, nonprofits that fulfill certain requirements are granted tax-exempt status by the Internal Revenue Service (IRS), preventing them from having to pay income tax. for credit union income will reduce federal revenue by $1.9 billion in 2019.[4] For the five-year period from 2018 to 2022, the JCT estimates the cost at nearly $10 billion.

The original purpose of credit unions shows that they generally have three distinguishing characteristics to justify their exemption from federal income taxes: a restricted customer base, low- and middle-income members, and types of services offered.

Common Bond of the Customer Base

The primary distinguishing characteristic of credit unions has been the requirement of a “meaningful, written, and enforced common bond for its members.”[5] The Federal Credit Union Act of 1934 limited membership of federal credit unions to people with “a common bond of occupation or association, or to groups within a well-defined neighborhood, community, or rural district.”[6]

Credit unions can only accept deposits from their members, and only make loans to their members.[7] So by narrowing a credit union’s field of membership to those with a common bond, for example to workers of a certain factory, credit unions were limited in their ability to directly compete with taxable financial institutions that had unrestricted customer bases.

Income of Membership

In 1934, the title describing the Federal Credit Union Act stated one of the purposes of establishing federally chartered credit unions was “…to make more available to people of small means credit for provident purposes through a national system of cooperative credit….”[8] When Congress revoked the tax-exempt status of some other financial institutions, they noted these institutions had a “principle purpose of serving…wage earners of moderate means who…had no other place where they could deposit their savings.”[9]

Thus, it has generally been understood that credit unions would use their tax savings to make financial services available to lower-income households that otherwise would not have access or would face prohibitive costs.[10]

Services Offered

According to the Internal Revenue Service, a “major reason for the establishment of credit unions in this country was to provide their members with a source of personal loans, in small amounts and for a short term, which generally were difficult to obtain from other financial institutions, absent the payment of usurious interest rates.”[11]

Credit unions face restrictions on the types and sizes of loans they can offer. For example, until 1977, most federal credit unions could not offer real estate loans.[12] In the past, credit unions primarily provided small-value, nonmortgage loans to individuals and households; credit union assets were chiefly loans to individuals.[13] These services were largely unavailable from traditional banks, especially for individuals of modest means during the Great Depression era.

Ultimately, credit unions have been expected to avoid high-risk, high-return investments in favor of safe, lower-interest investments, such as small personal loans.[14]

Evolution of the Industry

Since the inception of the credit union tax exemption, the financial sector has undergone significant changes. Likewise, research has determined that “the credit union industry has evolved over time such that many of the financial services that credit unions now provide are similar to those offered by banks and savings associations.”[15]

As of June 30, 2019, 5,308 federally insured credit unions were in operation, serving 118.32 million members and reporting $1.52 trillion in total assets.[16]

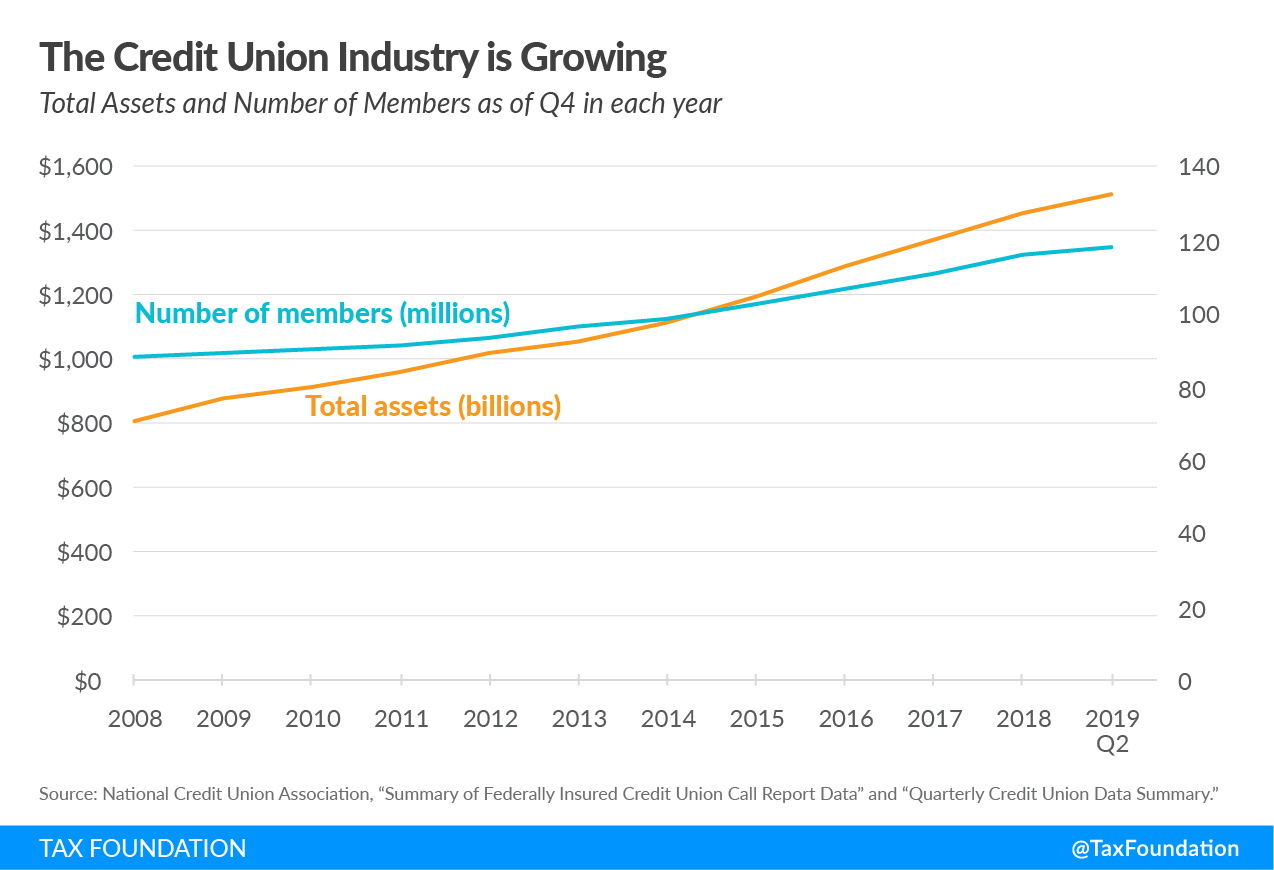

While the total number of credit unions has been in steady decline for decades—for example, in 1984 there were 18,375 credit unions—the industry is growing both in terms of members and assets, as illustrated in Figure 1. In 2008, the industry reported total assets of $885 billion and 88.6 million members. By the end of mid-2019, the industry’s assets surpassed $1.5 trillion while membership increased to more than 118 million.

Figure 1.

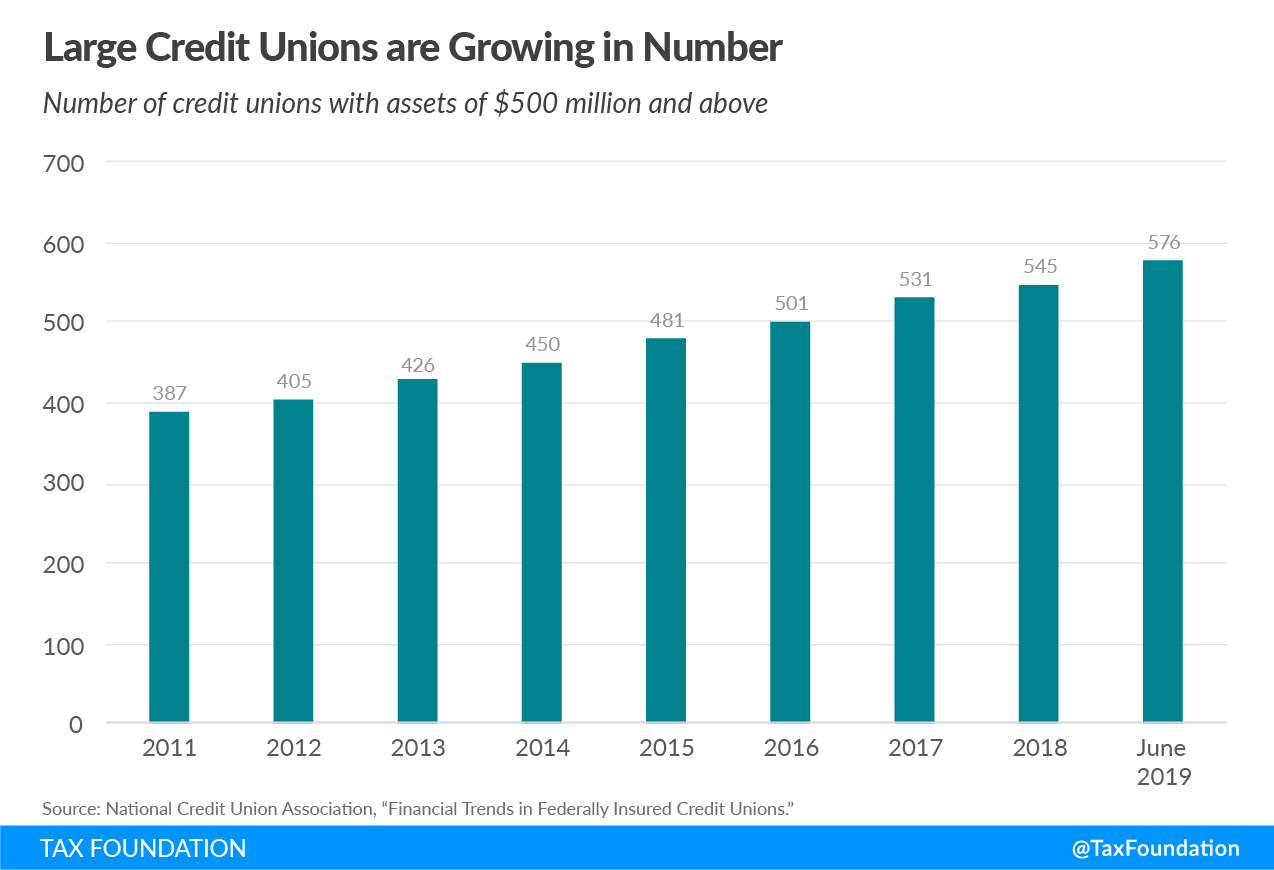

While the overall number of credit unions is falling, the industry itself is experiencing growth, indicating consolidation and growth in the number and size of “large” credit unions. As illustrated below, the number of credit unions with assets of $500 million and above is consistently increasing.

Figure 2.

The National Credit Union Association (NCUA) reports a “long-running trend” of credit unions with at least $1 billion in assets experiencing the most growth in loans, membership, and net worth. The number of these large credit unions reached 308 in the fourth quarter of 2018, up from 287 in the fourth quarter of 2017.[17] These largest credit unions held 66 percent of credit union assets, or $957.8 billion, again indicating concentration.[18]

This data shows that credit unions are growing rapidly, which means that the revenue lost from the tax exemption is likewise growing. Given the changes in the financial sector, it is useful to examine the extent to which credit unions fulfill their original purpose—serving low- to middle-income customers with a common bond and avoiding risky investments in favor of smaller, safer investments—to see whether continued tax exemption is warranted.

Common Bond Has Weakened

The field of membership limitation for credit unions has loosened over time. Though there are explanations why new types of common bonds have been allowed,[19] the weakening of this distinguishing factor indicates credit unions have strayed from their original purpose.

Expansion of the common bond definition began in the 1960s. In 1967, the requirement that members be “extensively acquainted” was replaced with a requirement that members “know each other,” and in 1968, lifetime membership was adopted.[20] Through the 1980s, the definition of common bond was repeatedly expanded, including a change which allowed credit unions to accept members from multiple groups. In 1998, the Supreme Court ruled against the expansion of the common bond definition. However, Congress followed up by enacting the Credit Union Membership Act of 1998, which permitted the multiple common bond definition.[21]

The common bond of members, which greatly limited credit union’s ability to compete with other financial institutions, was an original case made for the tax exemption. Contrast that to today, where there are credit unions that “anyone can join.”[22] The New York Times states it plainly in a 2010 article: “So many people haven’t gotten the message yet, that it’s worth repeating again, once more, with feeling. Anyone can join a credit union. And until the industry regulator stops allowing many of the biggest credit unions to offer services to anyone who shows up or logs in, you’d be foolish not to check out a few the next time you need financial services.”[23]

Higher-Income Customers at Credit Unions

Credit unions were originally designed to serve wage earners of small or moderate means. As described by The New York Times, credit unions received a tax exemption from the beginning “when they formed to serve customers that banks wouldn’t touch….”[24] However, evidence indicates that credit unions are not serving this purpose.

A 1989 study found that people in low-income households were less likely to belong to credit unions than people in middle- and upper-income households.[25] More recently, a study by the Government Accountability Office (GAO) using Federal Reserve survey data from 2001 and 2004 found that “credit union customers had a higher median income than bank customers” and that “credit unions served a lower proportion of households of modest means (low- and moderate-income households, collectively) than banks.”[26]

Expansion of Services Offered by Credit Unions

Many services now offered by credit unions resemble those offered by banks. In a letter to the NCUA, former Senate Finance Chairman Orrin Hatch (R-UT) noted,

Recent actions by the NCUA have…opened the door to the use of alternative capital, and lifted limits on other activity, such as business lending, which has traditionally been less associated with the mission of tax-exempt credit unions. While these may be worthwhile pursuits, they should give us pause and cause a reflection on the core mission of credit unions and their tax-exempt purpose.[27]

The letter went on to point out several services and activities that are beyond the scope of the credit union mission, including insurance products, real estate brokering and wealth management, purchasing previously for-profit banks, and buying naming rights to sports stadiums.

The credit union industry has repeatedly tried to lift limits on what activities it can undertake, such as the caps on its business lending. Currently, lending to member businesses in excess of $50,000 is limited and business loans may not exceed 1.75 percent of a credit union’s net worth or 12.25 percent of a credit union’s total assets (whichever is lesser).[28] But, credit unions sought and won approval to do business lending through the Small Business Administration; these loans, along with loans that are under $50,000, are not subject to the caps.[29] Credit unions have also pushed to increase the limitations on loans and to exclude certain other business loans from the cap.

While these changes in services may align with broader changes in the financial sector, they do not align with the original, tax-exempt status of credit unions.

Reasons to Repeal the Credit Union Exemption

In 1951, lawmakers revoked the tax-exempt status of several other types of financial institutions while retaining the credit union exemption. As explained in the Senate Report of the Revenue Act of 1951,[30]

Mutual savings banks were established to encourage thrift and to provide safe and convenient facilities to care for savings. They also have the responsibility of investing the funds left with them so as to be able to give their depositors a return on their savings. Mutual savings banks were originally organized for the principal purpose of serving factory workers and other wage earners of moderate means who, at the time these banks were started, had no other place where they could deposit their savings.

At the present time, mutual savings banks are in active competition with commercial banks and life insurance companies for the public savings, and they compete with many types of taxable institutions in the security and real estate markets. As a result, your committee believes that the continuance of the tax-free treatment now accorded mutual savings banks would be discriminatory. So long as they are exempt from income tax, mutual savings banks enjoy the advantage of being able to finance their growth out of earnings without incurring the tax liabilities paid by ordinary corporations when they undertake to expand through the use of their own reserves. The tax treatment provided by your committee would place mutual savings banks on a parity with their competitors.

The grounds on which your committee’s bill taxes savings and loan associations on their retained earnings, after making a reasonable allowance for additions to a reserve for bad debts, are the same as those on which mutual savings banks are taxed under the bill. Moreover, since savings and loan associations are no longer self-contained cooperative institutions as they were when originally organized there is relatively little difference between their operations and those of other financial institutions which accept deposits and make real-estate loans.

This passage indicates that Congress repealed the tax exemption for some financial institutions because they had evolved from their original purpose to resemble taxable banks. Thus, it is fair to assume lawmakers allowed credit unions to retain their exemption because they had not departed from their original purpose and did not resemble taxable financial institutions.

In 1979, when discussing how Congress revoked the tax exemption for other financial institutions in 1951, the IRS noted, “Had credit unions resembled taxable financial institutions at that time, it seems probable that Congress might not have continued their exempt status.”[31] In the years since, the credit union industry has grown in size, expanded in scope, appears to have little distinction from banks, and engages in activities like that of their taxed competitors—reasons for lawmakers to consider repealing the credit union tax exemption.

As it stands today, the exemption for credit unions violates at least two principles of sound tax policy: neutrality and efficiency. The principle of neutrality requires taxing similar economic activities the same. Taxing some financial institutions that provide similar, or even the same, services while not taxing others violates this principle. Non-neutrality in the tax code leads to a misallocation of resources: the tax-exempt industry can grow at the expense of the taxed industry, leading the tax-exempt industry to become larger and less productive than the taxed industry. In the absence of preferential treatment, this inefficient diversion of resources would not occur.

Repealing the credit union tax exemption would make the tax code more equitable by treating similar economic activity the same. Additionally, it would provide lawmakers with revenue that could be used to make improvements to other areas of the tax code.[32]

Conclusion

Credit unions were granted tax-exempt status with the understanding that they would use their tax savings to serve tight-knit groups of customers of moderate means who could not access financial services at banks. However, in the decades since, credit unions have grown to resemble banks. The common bond of their members has been watered down to the point that there are credit unions anyone can join. Credit unions are not more likely than banks to serve lower-income households, and evidence indicates that credit union members may be more well off than bank customers. Finally, credit unions have begun offering services and engaging in activities that have traditionally been offered by taxable financial institutions.

The tax exemption for credit unions is not justifiable under principles of sound tax policy, nor under the rubric that lawmakers have used in the past to evaluate the tax-exempt status of financial institutions. Credit unions compete with banks for similar customers and offer similar financial services but do so with the benefit of not paying the taxes that their competition must pay. Ending this disparate treatment would improve the neutrality of the tax code and provide revenue that could be used to make pro-growth changes.

Notes

[1] State-chartered credit unions are not exempt from state income taxes, franchise taxes, property taxes, or sales taxes in many states. Income of state-chartered credit unions that falls under the definition of unrelated business income is subject to taxation; however, federal credit unions are not subject to unrelated business income requirements.

[2] 12 U.S. Code § 1768. Taxation, https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/12/1768.

[3] Government Accountability Office, “Credit Unions: Reforms for Ensuring Future Soundness,” July 10, 1991, 290, https://www.gao.gov/products/GAO/GGD-91-85.

[4] The Joint Committee on Taxation, “Estimates Of Federal Tax Expenditures For Fiscal Years 2018-2022,” Oct. 4, 2018, https://www.jct.gov/publications.html?func=startdown&id=5148.

[5] Internal Revenue Service, “Exempt Organizations Continuing Professional Education Text,” 1979, https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-tege/eotopicm79.pdf.

[6] Government Accountability Office, “Credit Unions: Reforms for Ensuring Future Soundness,” 9.

[7] Credit unions do make loans to other credit unions and credit union corporations, and they can accept deposits and make loans to nonmembers under certain conditions. See John A. Tatom, “Competitive Advantage: A Study of the Federal Tax Exemption for Credit Unions,” Tax Foundation, Feb. 28, 2005, https://taxfoundation.org/competitive-advantage-study-federal-tax-exemption-credit-unions/.

[8] Government Accountability Office, “Credit Unions: Reforms for Ensuring Future Soundness,” 25.

[9] Senate Report No. 781, 1951-2 C.B. 476 and 478 as cited in Donald J. Marples, “Taxation of Credit Unions: In Brief,” Congressional Research Service, Mar. 31, 2016.

[10] Tatom, “Competitive Advantage: A Study of the Federal Tax Exemption for Credit Unions.”

[11] Internal Revenue Service, “Exempt Organizations Continuing Professional Education Text.”

[12] Ibid.

[13] John R. Walter, “Not Your Father’s Credit Union,” FRB Richmond Economic Quarterly 92:4 (Fall 2006), 361.

[14] William Ahern, “Tax-Exempt Credit Unions Get $30 Billion Bailout,” Tax Foundation, Sept. 26, 2010, https://taxfoundation.org/tax-exempt-credit-unions-get-30-billion-bailout.

[15] Marples, “Taxation of Credit Unions: In Brief.”

[16] National Credit Union Administration, “Quarterly Credit Union Data Summary,” 2019 Q2, https://www.ncua.gov/files/publications/analysis/quarterly-data-summary-2019-Q2.pdf.

[17] National Credit Union Administration, “Quarterly Credit Union Data Summary 2018 Q4,” https://www.ncua.gov/files/publications/analysis/quarterly-data-summary-2018-Q4.pdf.

[18] Ibid.

[19] For example, limiting members to workers of one factory or one association meant credit unions lacked diversity, which could make them more susceptible to risk.

[20] Government Accountability Office, “Credit Unions: Reforms for Ensuring Future Soundness,” 217.

[21] Marples, “Taxation of Credit Unions: In Brief.”

[22] Miriam Cross, “Best Credit Unions Anyone Can Join, 2018,” Kiplinger, July 6, 2018, https://www.kiplinger.com/slideshow/saving/T005-S002-best-credit-unions-anyone-can-join-2018/index.html, and “The Big List of Credit Unions Anyone Can Join,” DepositAccounts, Nov. 17, 2011, https://www.depositaccounts.com/credit-unions/anyone-can-join/.

[23] Rob Lieber, “Credit Unions are Beckoning With Open Arms,” June 18, 2010, The New York Times, https://www.nytimes.com/2010/06/19/your-money/brokerage-and-bank-accounts/19money.html?pagewanted=all&_r=1.

[24] Rob Lieber, “Credit Unions are Beckoning With Open Arms,” The New York Times, June 18, 2010, https://www.nytimes.com/2010/06/19/your-money/brokerage-and-bank-accounts/19money.html?pagewanted=all&_r=1.

[25] Government Accountability Office, “Credit Unions: Reforms for Ensuring Future Soundness,” 224-225.

[26] Government Accountability Office, “Credit Unions: Greater Transparency Needed on Who Credit Unions Serve and on Senior Executive Compensation Agreements,” Nov. 30, 2006, 51-53, https://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-07-29.

[27] Chairman Orrin Hatch, United States Senate Committee on Finance, Letter to The Honorable J. Mark McWatters, Jan. 31, 2018, http://icba-now.informz.net/icba-now/data/images/NWT/Documents/HatchLTR.pdf.

[28] Marples, “Taxation of Credit Unions: In Brief.”

[29] Tatom, “Competitive Advantage: A Study of the Federal Tax Exemption for Credit Unions.”

[30] Senate Report No. 781, 1951-2 C.B. 476 and 478 as cited in Marples, “Taxation of Credit Unions: In Brief.”

[31] Internal Revenue Service, “Exempt Organizations Continuing Professional Education Text.”

[32] See Robert Bellafiore, “Amortizing Research and Development Expenses Under the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act,” Tax Foundation, Feb. 5, 2019, https://taxfoundation.org/research-development-expensing-tcja/.

Share this article