Key Findings

- The taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. code contains several provisions designed to make higher education more affordable and to encourage educational attainment. These include credits, deductions, exclusions, and tax-neutral savings plans.

- Many of these benefits overlap and are complex, creating confusion for taxpayers that leads to underutilization of current policies as well as administrative and oversight difficulties.

- Research shows that the current menu of education-related benefits is not effectively promoting affordability or the decision to attend college.

- Lawmakers wishing to provide education assistance should reconsider whether the tax code is the best tool to achieve that goal.

Introduction

The tax code contains several provisions which are intended to make higher education more affordable. While traditionally the goal of affordability was pursued with loan programs and direct subsidies,[1] the policy toolkit now contains at least a dozen tax-related provisions such as credits and deductions.

Some provisions are available after education expenditures are made, while others are designed to incentivize long-term savings for higher education. Despite being touted as benefits for lower- and middle-income taxpayers, a disproportionate share of the provisions’ benefits flow to higher-income earners. Many of the benefits overlap and create confusion for taxpayers, while evidence is lacking as to whether these provisions work and whether they result in higher levels of education.

This leads to questions of whether the tax code is the most effective way for lawmakers to address the affordability of higher education, or whether traditional means offer a better way to pursue this goal.

This paper provides background information on the arguments for and against education-related tax provisions; an overview of the different provisions under current law, including how they function, who they benefit, and what they cost; and a discussion of areas lawmakers should evaluate when looking to reform these provisions.

Background

Two of the primary considerations for the tax treatment of education expenditures are whether they constitute investment spending or consumption spending, and whether higher education creates a social benefit.[2] For the tax code to be neutral, it should not affect a household’s decision whether to invest or consume. This can be easily illustrated with an example:

The tax treatment of an investment in an Individual Retirement Account (IRA) is neutral. A person may save $1,000 pretax in an IRA, and then pay income taxes when taking distributions from the account—resulting in one layer of tax. Likewise, if the person wished to immediately spend their income on consumption they would face only one layer of federal income tax. This individual would pay just one layer of federal income tax on their income whether they invest it or spend it immediately. Their decision is unaffected by the tax code. On the other hand, the tax code would create a bias against the investment if both the principle placed in the IRA and the return earned on the IRA were subject to tax.

It can be argued that higher education is an investment in human capital, similar to investments in physical capital. Individuals pay for higher education in order to earn higher income in the future, on which income taxes will be paid—in other words, education is the cost of investment in human capital and should be tax-deductible.[3]

This theory makes sense when viewed in the light that “individuals should be allowed to deduct from their income the expenses incurred as part of earning that income.”[4] This argument would favor a simple, above-the-line deduction for educational expenses.

However, if portions of education-related expenditures represent consumption, rather than investment, it would call for different tax treatment. To the extent that students obtain utility from pursuing higher education, the consumption portion of spending, it should not be deducted and instead taxed as any other type of consumption.[5]

If the mix of deductions and tax credits available to a student more than offset the cost of obtaining an education, this would in effect serve as a subsidy for education. For a subsidy to be justified, it would need to de demonstrated that higher education creates positive social returns, or benefits which spill over to society at large.[6]

The likely answer is that higher education expenditures represent a mix of investment and consumption spending, which has conflicting implications for the appropriate tax treatment.

Education Provisions under Current Law

The size and scope of education provisions in the tax code have greatly expanded over the past two decades.[7] A mix of credits, deductions, exclusions, and savings plans[8] are available to households as they plan and pay for higher education. The stated intent of many of these policies, especially the tax credits, is to increase investment in higher education and provide a tax cut to middle-class households that invest in higher education to make it more affordable.[9]

Credits

Two permanent credits, the American Opportunity Credit and the Lifetime Learning Credit, provide tax benefits for tuition and related expenses.

The American Opportunity Credit[10] provides a maximum annual amount of $2,500 per student, calculated as 100 percent of the first $2,000 in qualifying expenses and 25 percent of the next $2,000 in qualifying expenses for the first four years of undergraduate education. If the credit reduces a taxpayer’s liability to zero, then up to $1,000 may be refunded. The credit is subject to income limits: to claim the full credit, modified adjusted gross incomeFor individuals, gross income is the total pre-tax earnings from wages, tips, investments, interest, and other forms of income and is also referred to as “gross pay.” For businesses, gross income is total revenue minus cost of goods sold and is also known as “gross profit” or “gross margin.” (MAGI)[11] must be below $80,000 for single taxpayers ($160,000 married filing jointly). Taxpayers cannot claim the credit if MAGI exceeds $90,000 ($180,000 married filing jointly).

The Lifetime Learning Credit[12] provides a maximum annual amount up to $2,000 per tax return, calculated as 20 percent of the first $10,000 of qualified expenses, and it is nonrefundable. The Lifetime Learning Credit is subject to income limitations: for tax year 2018, the amount phases out if MAGI is between $57,000 and $67,000 ($114,000 and $134,000 married filing jointly) and cannot be claimed if MAGI exceeds that threshold.

| Provision | Annual Limit | Qualifying Expenses | Qualifying Education Level | Income Phaseout |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| American Opportunity Tax Credit | Partially refundable credit of up to $2,500 per student | Tuition and required enrollment fees Course-related books, supplies, and equipment | First four years of undergraduate education | $80,000-$90,000 (single) $160,000-$180,000 (married joint) |

| Lifetime Learning Credit | Nonrefundable credit of up to $2,000 | Tuition and required enrollment fees | Undergraduate, graduate, and job skills courses | $57,000-$67,000 (single) $114,000-$134,000 (married joint) |

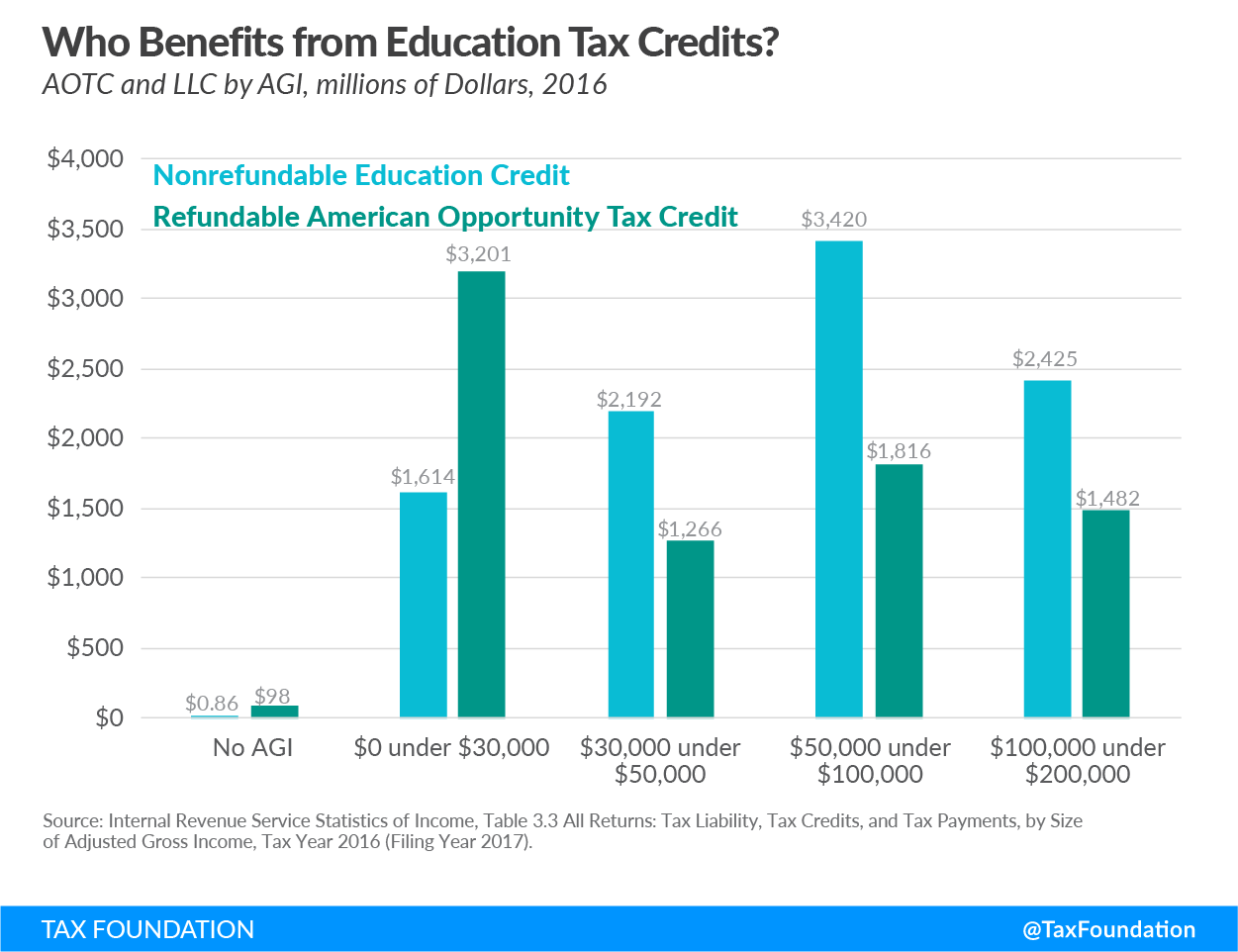

Taxpayers cannot claim more than one education benefit for the same students and the same expenses;[13] instead they must choose which education benefit is best for their situation. In tax year 2016, nearly 9 million returns claimed nonrefundable education credits,[14] while 8.7 million claimed refundable American Opportunity Credits. The average credit sizes for filers with $30,000 to $50,000 in AGI were $1,054 for nonrefundable credits and $859 for the refundable portion of the American Opportunity Credit (see Appendix Table 1).[15]

The Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) estimates that in 2018, the credits for postsecondary education cost $18.9 billion.[16] Over the five-year period from 2018 to 2022, the JCT estimates they will cost $95.5 billion.

Deductions

The tax code provides one permanent and one temporary deduction related to higher education costs: the Student Loan Interest Deduction and the Tuition and Fees deduction, which at the time of writing had expired.[17] Both are “above-the-line” deductions, which means taxpayers do not have to itemize in order to take the deductions.

The Student Loan Interest Deduction[18] allows taxpayers to deduct up to $2,500 of qualifying interest paid during the year. The deduction phases out for MAGI between $65,000 and $80,000 for single filers and between $135,000 and $165,000 for married filing jointly.

The Tuition and Fees Deduction allowed taxpayers to deduct up to $4,000 of qualified expenses. Taxpayers could not take the deduction if they claimed either of the two higher education tax credits, if the expenses were paid using certain monies,[19] or if MAGI exceeded $80,000 (or $160,000 married filing jointly). Because both tax credits are a permanent part of the code, generally provide a larger benefit, and cannot be used in conjunction with the deduction, most taxpayers utilize the credits rather than the deduction.[20] However, the deduction is beneficial for taxpayers who do not qualify for the credit.

The Tuition and Fees deduction is part of a group of tax provisions which are enacted on a temporary basis, regularly expire, and are then reauthorized on a temporary basis. At the time of writing, this deduction had expired.

| Provision | Annual Limit | Qualifying Expenses | Qualifying Education Level | Income Phaseout |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| * At the time of writing, this deduction had expired. | ||||

| Source: Margot L. Crandall-Hollick, “Higher Education Tax Benefits: Brief Overview and Budgetary Effects,” Congressional Research Service, Aug. 27, 2018. | ||||

| Student Loan Interest Deduction | Up to $2,500 deduction | Tuition and required enrollment fees Course-related books, supplies, and equipment Room and board Other necessary expenses, including transportation | Undergraduate and graduate | $65,000-$80,000 (single) $135,000-$165,000 (married joint) |

| Tuition and Fees Deduction* | Up to $4,000 deduction | Tuition and required enrollment fees | Undergraduate and graduate | $65,000-$80,000 (single) $130,000-$160,000 (married joint) |

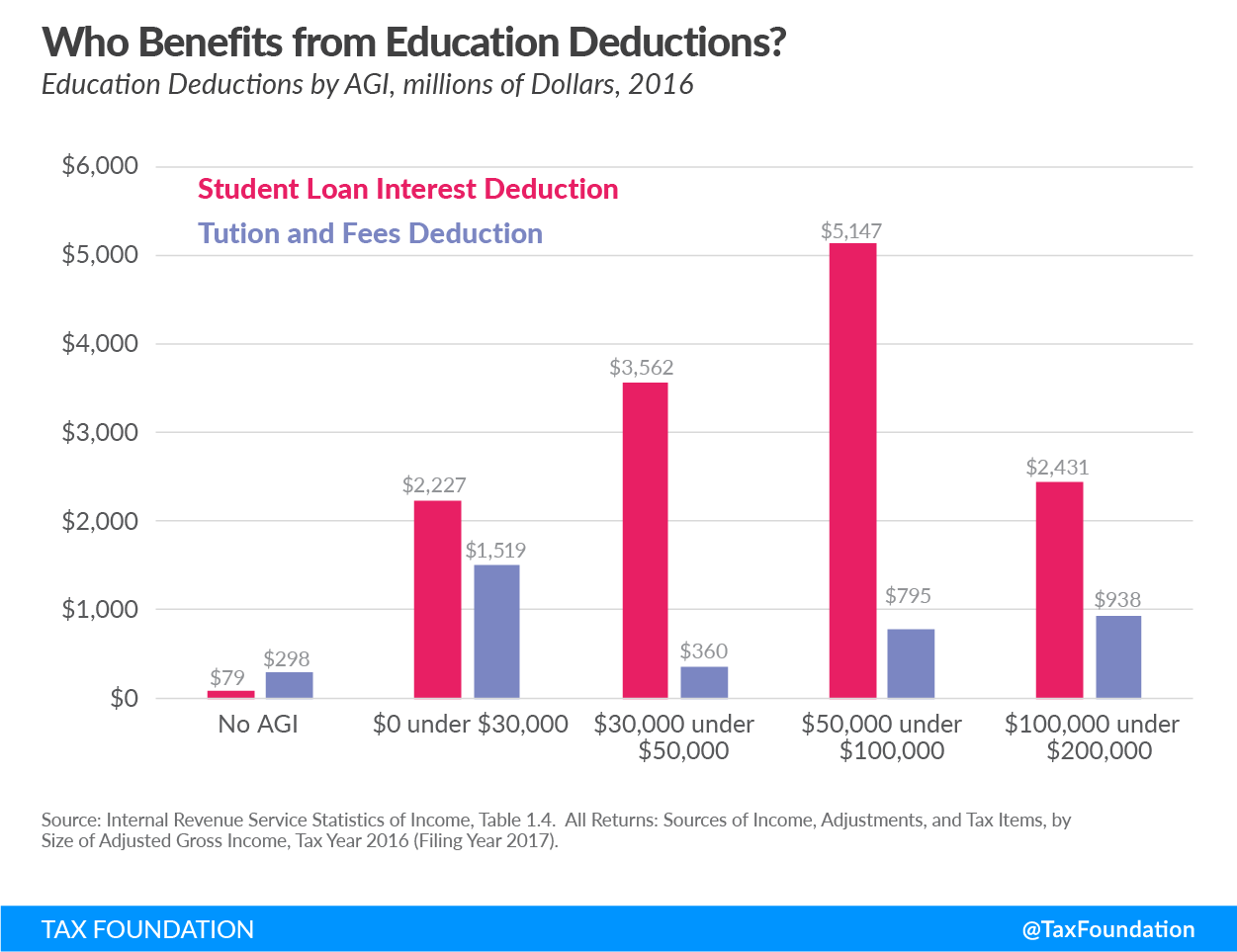

In tax year 2016, 12.4 million returns claimed the student loan interest deduction for a total of $13.4 billion while 1.7 million claimed the tuition and fees deduction for a total of $3.9 billion. In 2016, taxpayers with AGI between $30,000 to $50,000 took an average tuition and fees deduction of $2,207 and an average student loan interest deduction of $1,142 (see Appendix Table 2).

Note that the value of a deduction varies with the marginal tax rate of the taxpayer; for example, deducting $4,000 against a 22 percent tax rate reduces tax liability by $880, while deducting the same $4,000 against a 12 percent tax rate reduces tax liability by $480.[21]

The JCT estimates the student loan interest deduction cost $2.2 billion for 2018 and will cost $11.8 billion for the five-year period from 2018 to 2022.[22] Because the tuition and fees deduction had expired, it is not included in current expenditure reports. However, in a May 2018 report, the JCT estimated the 2017 revenue cost of the deduction for higher education expenses at $0.4 billion.[23]

Exclusions

Several types of education-related income are excluded from taxable income:[24] scholarships, grants, and tuition reductions; certain discharged student loans; and employer-provided education assistance.

- As long as scholarships, grants, and tuition reductions are used to pay for qualifying expenses and are not work-based, there is no limit on the amount that may be excluded from income.

- If students work for a certain period in certain professions, their student loan debt may be canceled, and that cancellation is not included in taxable incomeTaxable income is the amount of income subject to tax, after deductions and exemptions. For both individuals and corporations, taxable income differs from—and is less than—gross income. . Likewise, the cancellation of student debt due to death or permanent disability of a student is nontaxable.

- If an employee receives education assistance from their employer under a qualified program, up to $5,250 may be excluded from the employee’s taxable income.

The JCT estimates that in 2018, the exclusion for scholarship and fellowship income cost $3.0 billion, the exclusion of income attributable to the discharge of certain student loan debt and loan repayments cost $0.2 billion, the exclusion of employer-provided tuition reduction benefits cost $0.3 billion, and the exclusion of employer-provided education assistance benefits cost $1.1 billion.[25] Over the five-year period from 2018 to 2022, these exclusions together are estimated to cost $25.1 billion.

Tax-Neutral Savings Accounts

Lawmakers have also created a variety of college savings vehicles, which allow taxpayers to set aside funds that can grow tax-free.

529 Plans

529 Plans[26] can be established for a designated beneficiary to take tax-free withdrawals to pay for qualifying education expenses, such as tuition, fees, books, supplies, equipment, and room and board at eligible institutions and up to $10,000 of tuition at elementary or secondary schools.[27] While there are no income limits for contributors or beneficiaries of 529s, overall lifetime limits for contributions range from $250,000 to nearly $400,000 per beneficiary. The tax code provides two types of 529 plans.

The first type of account, a 529 “prepaid” plan, allows the contributor to save for a specified number of academic periods, course units, or percentage of tuition costs at current prices. This type of plan essentially purchases education at today’s price to be used in the future. The JCT estimates that this was a negative tax expenditureTax expenditures are a departure from the “normal” tax code that lower the tax burden of individuals or businesses, through an exemption, deduction, credit, or preferential rate. Expenditures can result in significant revenue losses to the government and include provisions such as the earned income tax credit (EITC), child tax credit (CTC), deduction for employer health-care contributions, and tax-advantaged savings plans. of $3 billion in 2018, but over the five-year period from 2018 to 2022 will reduce federal revenues by $0.3 billion.[28]

The second type, a 529 “savings plan,” allows contributors to invest savings that can later be withdrawn tax-free for education purposes. The JCT estimates this will reduce federal revenues by $1.0 billion in 2018, and by $7.2 billion over the five-year period from 2018 to 2022.[29]

Coverdell Education Savings Accounts

Coverdell education savings accounts[30] are tax-neutral accounts which allow taxpayers to save and then make tax-free withdrawals to pay for higher-education, elementary, and secondary school expenses. The JCT estimates that Coverdell accounts will reduce federal revenue by $0.1 billion in 2018 and $0.6 billion between 2018 and 2022.[31]

Contributions are limited to $2,000 a year per beneficiary (usually the taxpayer’s dependent), unless the contributor’s income exceeds $110,000 ($220,000 for married filing jointly), in which case contributions are prohibited. However, contributions may be gifted to an intermediary individual under the income limit and the intermediary may contribute the gift to the Coverdell.

Miscellaneous

In addition to the two categories of savings accounts, the tax code contains other provisions which provide preferential tax treatment for funds used for education.

First, taxpayers may take early distributions from any type of IRA to use for education costs without paying the 10 percent tax on early distributions.[32] Another option is that taxpayers may cash in savings bonds to use for education costs without paying tax on the interest, as long as they make no more than $93,150 ($147,250 married filing jointly).[33] And finally, a direct transfer to an educational institution to pay for tuition on behalf of a minor is not a taxable gift.[34]

Reform Considerations

The structure of the education provisions creates a host of problems and falls short of ideal tax policy, as well as the stated intent of the programs. Specifically, issues arise with regard to neutrality, administrability, simplicity, and efficiency.

Neutrality

When determining the appropriate tax treatment for higher education, Congress should consider that there are both investment and consumption elements to higher education. Research also indicates that at least some education may be a form of signaling to employers, and as such there may be an over-investment in higher education. [35]

Given these elements of educational expenses, it is not straightforward that the tax code should subsidize education.

While theory would suggest that it is neutral to allow a deduction for educational expenditures in that they reflect an investment, it would not be neutral to allow a deduction for, or to subsidize, the consumption and signaling components of educational expenses.

As previous Tax Foundation research suggests, “Overall, the net effect of these conflicting proper tax policies suggests that actually allowing no deductibility and having little subsidization of higher education may be the proper policy.”[36]

Recently, Senators Amy Klobuchar (D-MN) and Ben Sasse (R-NE) introduced Senate Bill 275 which would provide lifelong learning accounts to pay for education expenses including skills training, apprenticeships, and professional development.[37] This raises another neutrality issue: most tax provisions apply to undergraduate or graduate level education, and not other types of education.

Administrability and Simplicity

The mix of credits and deductions under current law creates a complex system of education provisions which taxpayers must navigate.

For example, eligibility for the American Opportunity Credit, the Lifetime Learning Credit, and the tuition and fees deduction can overlap, leaving families to decide which to claim for each student.

In 2009, the Government Accountability Office found that about 14 percent of filers failed to claim a credit or deduction for which they appeared eligible, leaving an average of $466 on the table for a total of $726 million.[38] The report also found that another 275,000 made a suboptimal choice of which credit or deduction to claim, with the result of failing to increase their tax benefit by an average of $284.[39] With a simpler system, filers could more easily find the credits and deduction they qualify for.

These complexities lead to administrative problems as well. Similar to the difficulty taxpayers face in navigating the swath of provisions, the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) is not well suited to be a benefits agency. The IRS lacks many of the resources and competencies required to educate taxpayers about the provisions and undertake enforcement actions necessary to prevent fraud. The Treasury Inspector General for Tax Administration (TIGTA) released a report in 2011 that found billions of dollars of education credits that appeared to be erroneous. Some of the key findings included:[40]

- 7 million taxpayers received $2.6 billion in education credits for students for whom there was no supporting documentation in IRS files that they attended an educational institution.

- 370,924 individuals claimed as students who were not eligible because they did not attend the required amount of time and/or were postgraduate students, resulting in an estimated $550 million in erroneous education credits.

- 63,713 taxpayers erroneously received $88.4 million in education credits for students claimed as a dependent or spouse on another taxpayer’s tax return.

If lawmakers want to provide tax benefits for higher education, they ought to consider consolidation so that the provisions are simpler for taxpayers and administrators to navigate. A simpler system would lead to greater understanding among filers and better administration at the IRS.

Efficiency

Given that lawmakers have decided that the tax code should be used to make higher education more affordable and help more individuals attend college,[41] we can evaluate whether current policies are successfully accomplishing those goals. Evidence suggests that they are not.

Despite the expanding size and scope of federal benefits for higher education, student loan debt is growing, reaching $1.56 trillion in Q3 2018.[42] The Federal Reserve has observed that “federal student loans are the only consumer debt segment with continuous cumulative growth since the Great RecessionA recession is a significant and sustained decline in the economy. Typically, a recession lasts longer than six months, but recovery from a recession can take a few years. ….Student loans have seen almost 157 percent in cumulative growth over the last 11 years.”[43] The growth in debt indicates that current policy is not addressing the fundamental issue of growth in the cost of college.[44]

Further, economic evidence casts doubt on the ability of the programs to even influence decisions of whether to pursue higher education. For example, a 2014 paper examined the federal tax credits and their effect on college outcomes, finding “no or very small causal effects” on attending college and further, that the federal government and society will earn zero return on the tax credits.[45] Another study by the same authors in 2015 found no evidence that the tuition and fees deduction affects attending college at all, attending full-time versus part-time, attending four- versus two-year college, or a number of other factors.[46]

Reform Discussions

These tax provisions fail to address the underlying causes of increasing costs for higher education, lead to complexity and administrability issues for taxpayers and the IRS, and violate principles of sound tax policy, all while not effectively helping the people Congress intended to help. Lawmakers have recently considered ways to consolidate the education provisions; however, a more thorough review is warranted.

Recent Efforts

An early version of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act in the House of Representatives included a subtitle, “Simplification and Reform of Education Incentives.”[47] This proposal would have consolidated the tax credits into a single, expanded American Opportunity Tax CreditA tax credit is a provision that reduces a taxpayer’s final tax bill, dollar-for-dollar. A tax credit differs from deductions and exemptions, which reduce taxable income rather than the taxpayer’s tax bill directly. . It would have consolidated Coverdell education savings accounts into section 529 plans, prohibiting new Coverdell contributions and allowing tax-free rollovers from Coverdell accounts into section 529 plans. It also would have repealed the deductions for interest payments on qualified education loans and tuition and fees and the exclusions for interest on U.S. savings bonds, qualified tuition reductions, and employer-provided education assistance.

Other Solutions

Past proposals range from addressing some overlapping provisions to adding even more options for taxpayers. These proposals have lacked the analysis necessary to be considered true reform. Consolidation of existing provisions should be pursued in conjunction with broader discussions about the effectiveness of tax-related policy tools compared to others that lawmakers could use.

For example, lawmakers could consider solutions that do not use the tax code to effectuate spending priorities and instead pursue policies such as Pell Grants and prepayment plans.[48] Focusing on spending programs like Pell Grants could better target government resources to lower-income students, as opposed to deductions and credits. Likewise, prepayment plans, such as the 529 “prepaid” plans, can help address affordability issues, as families are able to lock in prices and save for college.

Conclusion

The tax code contains several provisions relating to higher education affordability and attainment. Over the past few decades, these provisions have increased in size and scope, but evidence of whether they are accomplishing the stated goals is lacking. Many of the benefits flow to higher-income taxpayers, despite the rhetoric that these provisions are designed to help lower- and middle-income taxpayers. Likewise, research indicates that tax credits and deductions have little to no influence on whether an individual chooses to pursue higher education.

Lawmakers should address questions of administrability, simplicity, neutrality, and efficiency as they relate to the educational provisions. Questions of whether the tax code is the appropriate tool to work toward goals of affordability and attainment should also be explored. Options such as prepaid tuition plans and grants may be a more effective way to help manage the cost of education, while the efficacy of credits, exclusions, and deductions is less clear.

| Nonrefundable Education Credit | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| AGI | Number | Amount | Average |

| Source: IRS Table 3.3 All Returns: Tax Liability, Tax Credits, and Tax Payments, by Size of Adjusted Gross Income, Tax Year 2016 (Filing Year 2017), author’s calculations. | |||

| No AGI | 2,119 | $862,000 | $406.80 |

| $0 under $30,000 | 2555261 | $1,614,258,000 | $631.74 |

| $30,000 under $50,000 | 2,079,000 | $2,192,193,000 | $1,054.45 |

| $50,000 under $100,000 | 2,667,197 | $3,420,327,000 | $1,282.37 |

| $100,000 under $200,000 | 1,694,393 | $2,425,416,000 | $1,431.44 |

|

Refundable American Opportunity Tax Credit |

|||

|

AGI |

Number |

Amount |

Average |

| No AGI | 103,458 | $98,279,000 | $949.94 |

| $0 under $30,000 | 3,706,301 | $3,201,494,000 | $863.80 |

| $30,000 under $50,000 | 1,473,865 | $1,266,405,000 | $859.24 |

| $50,000 under $100,000 | 1,938,030 | $1,816,291,000 | $937.18 |

| $100,000 under $200,000 | 1,541,631 | $1,482,048,000 | $961.35 |

| Tuition and Fees Deduction | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| AGI | Number | Amount | Average |

| Source: IRS Table 1.4. All Returns: Sources of Income, Adjustments, and Tax Items, by Size of Adjusted Gross Income, Tax Year 2016 (Filing Year 2017), author’s calculations. | |||

| No AGI | 82,835 | $297,976,000 | $3,597.22 |

| $0 under $30,000 | 567,468 | $1,518,572,000 | $2,676.05 |

| $30,000 under $50,000 | 163,279 | $360,363,000 | $2,207.04 |

| $50,000 under $100,000 | 384,761 | $795,196,000 | $2,066.73 |

| $100,000 under $200,000 | 488,759 | $938,119,000 | $1,919.39 |

|

Student Loan Interest Deduction |

|||

|

AGI |

Number |

Amount |

Average |

| No AGI | 79,192 | $78,810,000 | $995.18 |

| $0 under $30,000 | 2,424,392 | $2,227,231,000 | $918.68 |

| $30,000 under $50,000 | 3,118,877 | $3,562,222,000 | $1,142.15 |

| $50,000 under $100,000 | 4,496,698 | $5,146,880,000 | $1,144.59 |

| $100,000 under $200,000 | 2,277,021 | $2,431,008,000 | $1,067.63 |

Notes

The author would like to thank Alec Fornwalt for his research contributions.

[1] Scott A. Hodge and Kyle Pomerleau, “Is the Tax Code the Proper Tool for Making Higher Education More Affordable?” Tax Foundation, July 15, 2014, https://taxfoundation.org/tax-code-proper-tool-making-higher-education-more-affordable/.

[2] See generally Michael Schuyler and Stephen J. Entin, “Case Study #8: Education Credits,” Tax Foundation, Aug. 7, 2013, https://taxfoundation.org/case-study-8-education-credits/.

[3] Gerald Prante, “Education Tax “Subsidies” – Justified or Not?” Tax Foundation, May 13, 2008, https://taxfoundation.org/education-tax-subsidies-justified-or-not/.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Michael Schuyler and Stephen J. Entin, “Case Study #8: Education Credits.”

[7] Ibid.

[8] A tax credit directly reduces tax liability. A deduction reduces the amount of income subject to tax. An exclusion excludes certain types or amounts of income from tax.

[9] George B. Bulman and Caroline M. Hoxby, “The Returns to the Federal Tax Credits for Higher Education,” National Bureau of Economics, December 2015, 27-29, https://www.nber.org/chapters/c13465.pdf.

[10] Internal Revenue Service, “American Opportunity Tax Credit,” https://www.irs.gov/credits-deductions/individuals/aotc.

[11] Modified adjusted gross income is the same as adjusted gross income for most tax filers. It is calculated by adding back certain exclusions and deductions to adjusted gross income. These include the foreign earned income exclusion, foreign housing exclusion, foreign housing deduction, and exclusion of income by bona fide residents of American Samoa or Puerto Rico. See Internal Revenue Service, “American Opportunity Tax Credit.”

[12] Internal Revenue Service, “Lifetime Learning Credit,” https://www.irs.gov/credits-deductions/individuals/llc.

[13] Internal Revenue Service, “Education Benefits — No Double Benefits Allowed,” https://www.irs.gov/credits-deductions/individuals/education-benefits-no-double-benefits-allowed.

[14] Meaning, the portion of the education credit the taxpayer used to offset tax liability and not receive as a refund.

[15] Internal Revenue Service Statistics of Income, Table 3.3 All Returns: Tax Liability, Tax Credits, and Tax Payments, by Size of Adjusted Gross Income, Tax Year 2016 (Filing Year 2017)

[16] Joint Committee on Taxation, “Estimates Of Federal Tax Expenditures For Fiscal Years 2018-2022,” Oct. 4, 2018, https://www.jct.gov/publications.html?func=startdown&id=5148.

[17] It is likely that Congress will reauthorize this provision.

[18] Internal Revenue Service, “Publication 970 (2017), Tax Benefits for Education,” https://www.irs.gov/publications/p970.

[19] For example, if expenses were paid using the tax-free portion of a distribution from a Covedell education savings account or qualified tuition program or other tax-free educational assistance.

[20] Joint Committee on Taxation, “Federal Tax Provisions Expired in 2017,” March 9, 2018, 20, https://www.jct.gov/publications.html?func=startdown&id=5062.

[21] Note that the maximum benefit of the tuition and fees deduction in 2018 would be $880, because eligible taxpayers would be in the 22 percent bracket or below.

[22] Joint Committee on Taxation, “Estimates Of Federal Tax Expenditures For Fiscal Years 2018-2022.”

[23] Joint Committee on Taxation, “Estimates Of Federal Tax Expenditures For Fiscal Years 2017 – 2021” May 25, 2018, https://www.jct.gov/publications.html?func=startdown&id=5095.

[24] See Internal Revenue Service, “Publication 970 (2017), Tax Benefits for Education.”

[25] Joint Committee on Taxation, “Estimates Of Federal Tax Expenditures For Fiscal Years 2018-2022.”

[26] Margot L. Crandall-Hollick, “Tax-Preferred College Savings Plans: An Introduction to 529 Plans,” Congressional Research Service, March 5, 2018, https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R42807.pdf.

[27] Internal Revenue Service, “Publication 970 (2018), Tax Benefits for Education,” 83.

[28] Joint Committee on Taxation, “Estimates Of Federal Tax Expenditures For Fiscal Years 2018-2022.”

[29] Ibid.

[30] Margot L. Crandall-Hollick, “Tax-Preferred College Savings Plans: An Introduction to Coverdells,” Congressional Research Service, March 13, 2018, https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R42809.pdf.

[31] Joint Committee on Taxation, “Estimates Of Federal Tax Expenditures For Fiscal Years 2018-2022.”

[32] Internal Revenue Service, “Publication 970 (2017), Tax Benefits for Education.”

[33] Ibid.

[34] 26 U.S. Code § 2503 – “Taxable gifts,” https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/26/2503.

[35] Gerald Prante, “Education Tax “Subsidies” – Justified or Not?”

[36] Ibid.

[37] Senate Bill 275 – “Skills Investment Act of 2019,” 116th Congress, https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/senate-bill/275?q=%7B%22search%22%3A%5B%22S.275%22%5D%7D&s=3&r=1.

[38] Government Accountability Office, “Higher Education: Improved Tax Information Could Help Families Pay for College,” May 2012, 27, https://www.gao.gov/assets/600/590970.pdf.

[39] Ibid.

[40] U.S. Department of the Treasury, “Recovery Act: Billions of Dollars in Education Credits Appear to be Erroneous,” Treasury Inspector General for Tax Administration, Sept. 16, 2011, https://www.treasury.gov/tigta/auditreports/2011reports/201141083fr.html.

[41] George B. Bulman and Caroline M. Hoxby, “The Returns to the Federal Tax Credits for Higher Education.”

[42] The Federal Reserve, “Consumer Credit outstanding (Levels),” Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, https://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/g19/HIST/cc_hist_memo_levels.html.

[43] Riley Griffin, “The Student Loan Debt Crisis Is About to Get Worse,” Bloomberg, Oct. 17, 2018, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2018-10-17/the-student-loan-debt-crisis-is-about-to-get-worse.

[44] Scott A. Hodge and Kyle Pomerleau, “Is the Tax Code the Proper Tool for Making Higher Education More Affordable?”

[45] George B. Bulman and Caroline M. Hoxby, “The Returns to the Federal Tax Credits for Higher Education.”

[46] Caroline M. Hoxby and George B. Bulman, “The Effects of the Tax Deduction for Postsecondary Tuition: Implications for Structuring Tax-Based Aid,” National Bureau of Economic Research, September 2015, https://www.nber.org/papers/w21554.

[47] Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, H.R. 1, As Ordered Reported by the Committee, Section-by-Section Summary, https://republicans-waysandmeansforms.house.gov/uploadedfiles/tax_cuts_and_jobs_act_section_by_section_hr1.pdf.

[48] Scott A. Hodge and Kyle Pomerleau, “Is the Tax Code the Proper Tool for Making Higher Education More Affordable?”

Share this article