Key Findings

- Credit unions are taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. -exempt nonprofit financial institutions that were originally organized to provide lending and saving services to low-income working and rural households.

- The Credit Union Act of 1934 set out the basic rules governing the “field of membership” and the “common bond” that defined credit union membership.

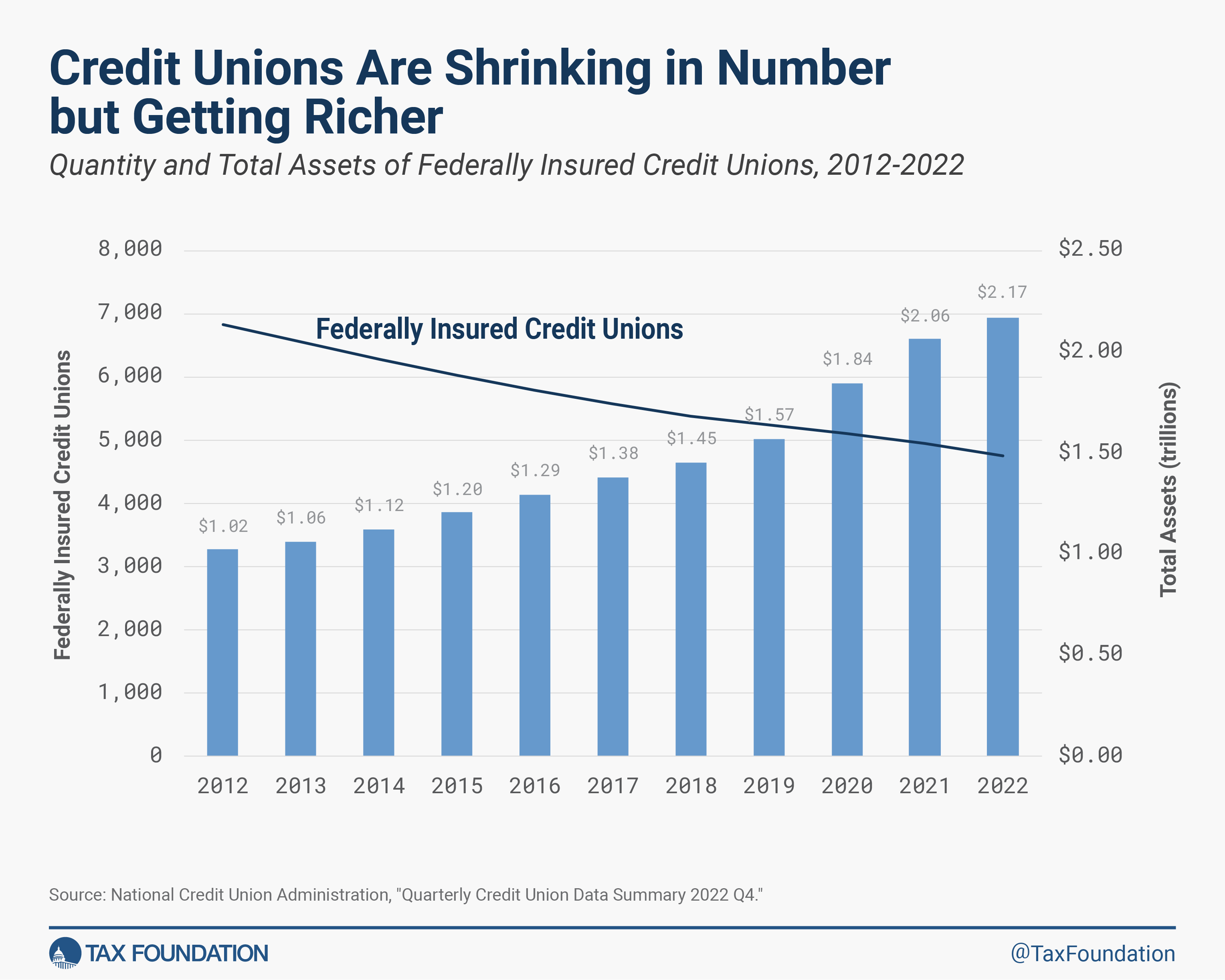

- Over the past decade, the number of credit unions has declined by 30 percent, but the amount of credit union assets has more than doubled, from $1.02 trillion to $2.17 trillion.

- Federal credit unions are a special class of nonprofit organizations that do not have to file a Form 990 tax return, which makes them less transparent and accountable than other nonprofits. State credit unions do have to file a Form 990 tax return.

- Credit unions benefit from both a tax subsidy and a nonprofit subsidy. The tax subsidy is roughly $3 billion annually, but studies find the combined subsidy is many times the tax subsidy, as much as $21 billion annually.

- Although credit unions are supposed to focus on people who are “underserved” and of “modest means,” they are not required to collect data or report on their progress in meeting this mission. Studies show that credit unions increasingly serve upper-income families and serve a smaller share of low-income customers than banks.

- The twin recessions during the early 1980s showed the vulnerability of the credit union business model. Since then, lawmakers have repeatedly relaxed membership rules and expanded the types of financial services credit unions can offer, so much so that credit unions look and act more like banks.

- Credit unions are now competing so successfully against banks that they are actually buying banks to further expand their membership and services.

- Mobile and online banking have made the rules governing the field of membership and common bond anachronisms. Some credit unions have no membership rules—anyone can become a member.

- Fairness and equity demand that credit unions be put on the same tax footing as the banks they compete with. In an era of $2 trillion deficits, subsidizing credit unions is a luxury taxpayers can no longer afford.

Introduction

When President Franklin Roosevelt signed into law the Credit Union Act of 1934,[1] it is unlikely the bill’s sponsors imagined that these “baby banks,” as Rep. Wright Patman (D-TX) called them during the floor debate,[2] would someday grow up to be profitable enough to buy commercial banks, sponsor sports stadiums, and cater to affluent customers. But 90 years later, that is what credit unions have become thanks to their privileged status as tax-exempt nonprofit financial institutions.

In an era of $2 trillion deficits, taxpayers can no longer afford to subsidize these successful financial institutions.

American credit unions were modeled on the “self-help financial cooperatives”[3] started in Germany during the 1850s when poor and rural people had little access to banking or lending. The idea was for people in a community—who have a “common bond”—to combine their resources into a lending pool accessible to those in need.

As Rep. Henry B. Steagall (D-AL) said in the minutes before the final vote on the bill, credit unions represent “an effort to help citizens solve their own economic problems and meet their own conditions of distress out of their own resources and by their own efforts. The system loans on character, a thing greatly to be desired.”[4]

Steagall and other supporters were motivated by the belief that expanding credit unions would undercut the “loan sharks” and “shot-gun loan offices” that charged excessive rates on loans to the poor and working class during the Great Depression.

That idealized image of credit unions did not shield them from criticism. By the 1950s, just 20 years after the enactment of the Credit Union Act of 1934, experts began asking, “Do Federal credit unions serve any useful purpose in the present-day American economy? Haven’t Federal credit unions expanded their services beyond the area visualized for them by the founders of the credit union movement? Shouldn’t the size of Federal credit unions be limited because some have grown beyond the point where they can continue to be a credit union as defined by the early philosophers of the movement?”[5]

Credit unions may have survived those early challenges by lawmakers and business groups—who claimed that the credit unions’ tax exemptionA tax exemption excludes certain income, revenue, or even taxpayers from tax altogether. For example, nonprofits that fulfill certain requirements are granted tax-exempt status by the Internal Revenue Service (IRS), preventing them from having to pay income tax. allowed them to unfairly compete with commercial banks—but the issues have not changed with time.

As we will see, the competitive gap between credit unions and banks has widened in the years since. Studies now show that credit unions enjoy a taxpayer subsidy much larger than the roughly $3 billion in forgone tax revenues estimated each year. The credit unions’ own association puts the total tax and nonprofit subsidy at some $21 billion annually. And despite their mandate to serve people of “small means,” credit unions are increasingly serving upper-income families, in part because that is where the profits are, but also because the number of Americans who are unbanked or underserved has nearly disappeared.

Indeed, many credit unions have no membership requirements—anyone can join. It stands to reason that if anyone in America can be a member of a credit union simply by opening an account online, then there are no more “underserved” in America; anyone with an internet connection or a phone can become “banked.”

In recent years, regulators and lawmakers have relaxed the rules governing credit unions’ “field of membership” and common bonds to such a degree as to make the terms meaningless. The unspoken motivation behind these relaxed rules is that the traditional credit union business model is no longer viable.

The twin recessions of the early 1980s showed that pinning credit union membership to a specific employer, profession, or community was a recipe for extinction because employers go bankrupt, professions become obsolete, and communities hollow out. The strategy lawmakers used to ensure the survival of vulnerable financial institutions was to relax their membership rules and allow them to expand the financial services they offer. In other words, allow credit unions to become more and more like banks.

Now that regulators and lawmakers permit credit unions to behave like banks, equity, fairness, and public finance require that they be taxed like the modern financial institutions they have become.

Credit Unions: Shrinking in Number but Growing in Size

As of December 2022, the most recent full-year data, there were 4,760 federally insured credit unions; 2,980 were federal credit unions and 1,780 were federally insured state credit unions. As Figure 1 illustrates, the number of credit unions has declined by 30 percent since 2012, but the amount of credit union assets has more than doubled, from $1.02 trillion to $2.17 trillion.[6]

While the number of credit unions declined during that period, the number of members grew. In 2012, credit unions had roughly 94 million members. By 2022, that number had grown to more than 135 million, a 44 percent increase.

As a result of consolidation and their expansion through relaxed common bonds, credit unions have become increasingly bigger. The typical credit union in 2012 had $150 million in assets. In 2022, the typical credit union had $455 million in assets, three times larger than the typical credit union a decade earlier.

Credit Unions Are a Special Class of Nonprofit Organizations

The original 1934 Act called for exempting credit unions from taxation, but that provision was removed due to objections from some lawmakers before final passage. Credit union sponsors were able to pass an amendment in 1937 reinstating the provision exempting all state and federally chartered credit unions from paying either federal or state income taxes. Credit unions were not exempted from paying local property taxes or payroll taxes.

In 1998, Congress used the Credit Union Membership Access Act to reinforce the notion that credit unions are exempt from federal income taxes “because they are member-owned, democratically operated, not-for-profit organizations generally managed by volunteer boards of directors and because they have the specified mission of meeting the credit and savings needs of consumers, especially persons of modest means.”[7]

Typically, nonprofit organizations are required to file a special Form 990 federal tax return each year to report on their finances, operations, and executive compensation. Form 990 tax returns are publicly available so donors, members, and stakeholders can hold nonprofits accountable, especially since most nonprofits are charities.

However, thanks to their special charter, federal credit unions may be the only fully private, non-religious organizations in America not required to file a tax return. Federal credit unions are considered to be “instrumentalities” of the federal government and are tax-exempt under 501(c)(1) of the Internal Revenue Code. This designation is reserved for organizations created or chartered by an act of Congress, such as the Corporation for Public Broadcasting and regional Federal Reserve banks.

And because federal credit unions are exempt from filing Form 990 tax returns, they lack the kind of transparency and accountability that members and taxpayers deserve. There is no independent way of determining if federal credit unions are meeting their mandated missions.

Moreover, federal credit unions are exempt from unrelated business income tax (UBIT) rules that require nonprofits to pay tax on income derived from commercial activities unrelated to the organization’s mission. Admittedly, UBIT rules have a lot of loopholes—for example, they allow college sports associations to collect millions of dollars in TV revenues tax-free—but exempting federal credit unions from UBIT gives them even more freedom to expand into businesses unrelated to serving underserved customers.

State credit unions are treated differently than federal credit unions. They are tax-exempt under 501(c)(14) of the IRS code and must file annual Form 990 tax returns. They are not exempt from UBIT. While tax returns don’t require information on the composition of a credit union’s membership or outreach to the underserved, they do provide members and the public with transparent information about the organization’s finances and operations.

In 2006, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) published a report highly critical of credit unions’ lack of transparency. The report highlighted credit unions’ failure to document which constituencies they serve and the compensation arrangements they have with their senior managers.

GAO warned, “Executive compensation for federal credit unions is not transparent, because credit unions are not required to file publicly available reports such as the IRS Form 990 that disclose executive compensation data.”[8] And state credit unions often file tax returns as a group, which allows them to avoid documenting executive compensation.

GAO recommended that the National Credit Union Administration (NCUA) develop the means to systematically track the performance of credit unions in serving underserved populations and provide transparency about executive compensation.

NCUA has not satisfactorily addressed either of the recommendations during the past 17 years.

Credit Unions Benefit from Explicit and Implicit Subsidies

Credit unions are both tax-exempt and nonprofit which, as we explore, provides them with both explicit and implicit subsidies. The most commonly understood explicit subsidy is the “tax expenditureTax expenditures are departures from a “normal” tax code that lower the tax burden of individuals or businesses through an exemption, deduction, credit, or preferential rate. However, defining which tax expenditures grant special benefits to certain groups of people or types of economic activity is not always straightforward. ” estimated annually by economists at Congress’s Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) and the U.S. Treasury. JCT’s estimate assumes that if all credit unions lost their tax exemption and were required to pay the 21 percent corporate tax rate on their net profits, they would owe $2.8 billion in corporate income taxA corporate income tax (CIT) is levied by federal and state governments on business profits. Many companies are not subject to the CIT because they are taxed as pass-through businesses, with income reportable under the individual income tax. in 2024 and $15.2 billion over five years. Using a slightly different methodology, Treasury economists estimate the credit union tax exemption results in forgone tax revenues of $34.7 billion over 10 years.

These estimates are rough calculations of what credit unions would pay in income tax on net profits if they were corporate entities. For example, according to NCUA data, in pre-COVID 2019, all federally insured credit unions (both federal and state-chartered) enjoyed collective net income—i.e., profits—of $14 billion,[9] which would have meant a $2.9 billion tax liability. In 2022, all federally insured credit unions enjoyed a collective net income of $18.8 billion,[10] which would translate to a tax liability of $3.9 billion.

An example of this tax subsidy at work can be found in a 2010 study published in the Southern Business Review comparing the return on investment (ROI) of credit unions versus the ROI of banks in Georgia. The study found that banks were generally more profitable than credit unions, “but, due to the credit unions tax exempt status, banks wind up earning less income as a percentage of assets.”[11]

However, a serious limitation of tax expenditure estimates is that they are a narrow attempt to approximate the corporate income taxes a credit union would pay on book profits, but don’t account for the implicit subsidies afforded tax-exempt organizations because of their nonprofit status. For example, federal credit unions save significant administrative costs by not having to file state and federal income tax returns. Nor do credit unions have to comply with other regulatory burdens commercial banks must account for, such as the Community Reinvestment Act. These exemptions should be considered implicit subsidies. Credit unions also may benefit from a perceived “good will” because of their nonprofit status.

More broadly, nonprofits enjoy numerous untaxed income streams outside of the bounds of UBIT, including investment and endowment income, certain rent and royalty income, and income from ticket sales and tuition, to mention a few examples. All of these income streams are taxable for corporate entities but not for nonprofits. Thus, they are ignored in the official calculation of tax expenditures.

To be sure, the nonprofit subsidy is more difficult to estimate. But as a 2021 study by economists Jordan van Rijn, Shuwei Zeng, and Paul Hellman demonstrates, it is many times larger than the simple tax expenditure estimate.[12] The researchers compared car loan rates charged by credit unions versus banks and found that the aggregate difference between them was 163 percent larger than the estimated value of the credit union tax exemption over an 18-year period. This suggests that even in the absence of the tax exemption, credit unions could still offer lower auto loan rates than banks due to their nonprofit status.

There is a larger macroeconomic implication of the implicit subsidy for nonprofits. As economist Don Fuller observed in a study on nonprofit museums, the “taxes levied on the rest of the economy serve to raise the cost of other activities relative to the cost of [nonprofit] activities. In this sense, we can say that there is an ‘implicit subsidy.’ With limited economic resources to go around, a tax system that discourages certain uses of resources necessarily encourages other untaxed uses of resources.”[13] In other words, the tax exemption encourages more nonprofit activities over profit-making (and tax-paying) activities than would otherwise be the case.

Subsidies Allow Credit Unions to Be Less “Profit Efficient” than Banks

In a 2022 study, economists Robert DeYoung, John Goddard, Donal G. McKillop, and John O.S. Wilson (DeYoung et al.) measured the “profit inefficiency” gaps of credit unions and comparably sized banks.[14] In other words, they looked at how far below profit maximization each financial institution was. Not surprisingly, credit unions were found to be more “inefficient” (meaning they maximized profits less) because of their tax-exempt and nonprofit status.

The profit inefficiency gap between credit unions and commercial banks was found to be 75 basis points per dollar of assets. The first question DeYoung et al. sought to answer was what was the cause of the gap? Was it due to the tax subsidy, the nonprofit subsidy, or something else?

Next, the study’s authors wanted to determine how credit unions use the profit inefficiency gap. Do they spend more on staffing, overhead, or executive salaries than banks? Do they provide depositors with higher interest rates on savings? Do they charge less on loans and credit cards? Or some combination of all three?

DeYoung et al. found that credit unions benefit from both the tax and nonprofit subsidies, although the tax subsidy was slightly more powerful than the nonprofit subsidy, leading to more than half (55 percent) of the benefits to credit union members.

Their model also indicated that the two subsidies largely flowed to depositors through higher rates on savings vehicles such as certificates of deposit, individual retirement accounts, and personal savings accounts. They did not find that the subsidies benefited borrowers or credit card users to any sizable degree. Credit unions were found to employ more personnel than banks but did not have excessive overhead costs compared to banks.

“Hence, we [DeYoung et al.] conclude that most of the tax and non-profit subsidies enjoyed by credit unions are simply redistributions, passed through from taxpayers to credit union depositors in the form of higher interest payments.”

The Congressional Record suggests that lawmakers’ purpose in granting credit unions a tax exemption was an acknowledgment of their self-help structure, not as a means of redistributing income from taxpayers to depositors.

The Cost of the Taxpayer Subsidy Is Larger than the Tax Expenditure

Now that we know that both the tax subsidy and the nonprofit subsidy explain the “profit inefficiency gap” between credit unions and banks, what is that gap worth? As it turns out, it is much more than the amount of forgone tax revenues estimated in the tax expenditure tables.

The Credit Union National Association (CUNA)—the credit unions’ lobby—publishes a regular report on benefits to members that provides a more complete measure of the size of the combined tax and nonprofit subsidy.

The CUNA report[15] compares the average interest rates credit unions offer on savings vehicles and the interest rates they charge on lending (auto loans, mortgages, and credit cards) with the averages provided by commercial banks. As DeYoung et al. showed in their study, the profit gap between credit unions and banks is more than just the tax subsidy; it also includes the nonprofit subsidy. Measuring the total dollar value of the difference between the rates offered by credit unions and banks should give us a truer measure of the combined tax-exempt and nonprofit subsidy.

As Table 1 illustrates, as of September 2023, credit unions charged interest rates 0.62 percentage points less on new auto loans and 4.70 percentage points less on credit cards than what commercial banks typically charged. Credit unions offered better rates on most other loan products as well. As a result, CUNA estimates that based on the combined loan balances of credit unions, the rate differentials totaled nearly $9.5 billion in financial benefits to members as of September 2023.

Table 1. Estimated Credit Union Financial Benefits September 2023

| Average Balance at Credit Unions (billions) | Percentage Point Rate Difference vs. Banks (%) | Total Financial Benefits to Members (billions) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

Loans | |||

| New car loans | $172.93 | -0.62 | $1.067 |

| Used car loans | $317.17 | -0.69 | $2.192 |

| Personal unsecured loans | $64.79 | 0.69 | ($0.450) |

| 5-year adjustable rate 1st mortgage | $162.54 | -0.92 | $1.492 |

| 15-year fixed rate 1st mortgage | $101.16 | -0.09 | $0.090 |

| 30-year fixed rate 1st mortgage | $298.34 | -0.19 | $0.564 |

| Home equity / 2nd mortgage loans | $113.79 | -0.78 | $0.890 |

| Credit cards | $746.57 | -4.7 | $3.611 |

| Interest rebates | $0.024 | ||

Total CU member benefit arising from lower interest rates on loan products: | $9.947 | ||

Savings | |||

| Regular shares | $638.45 | 0.01 | $0.045 |

| Share draft checking | $386.59 | 0.25 | $0.947 |

| Money market accounts | $380.02 | 0.42 | $1.577 |

| Certificate accounts | $353.67 | 1.96 | $6.918 |

| Retirement (IRA) accounts | $841.53 | 1.19 | $0.998 |

| Bonus dividends in period | $0.000 | ||

Total CU member benefit arising from higher interest rates on saving products: | $10.484 | ||

Fee Income | |||

Total CU member benefit arising from fewer/lower fees: | $1.500 | ||

Total CU member benefit arising from interest rates on loan and savings products and lower fees: | $21.464 |

Credit unions also offered better rates on savings products. For example, credit unions paid 1.19 percentage points more on individual retirement accounts and 0.42 percentage points more on money market accounts than banks. Across all the various savings products, the rate differentials added up to nearly $10.5 billion in financial benefits to members.

In addition, CUNA estimates the benefits to members of the lower fees charged by credit unions totaled $1.5 billion.

Combined, CUNA estimates the total financial benefits to members at more than $21 billion annually. The benefits are said to equal $156 per member and $328 per household.

However, what CUNA touts as the financial benefits members receive is actually a good approximation of the combined tax and nonprofit subsidies enjoyed by credit unions. Thus, the true taxpayer subsidy to credit unions totals more than $21 billion per year.

Although CUNA’s figures differ slightly from the figures of DeYoung et al.—for example, CUNA estimates that the benefits of lower loan rates are larger than the benefits from the higher savings rates—the figures nonetheless illustrate that the true taxpayer subsidy to credit unions is many times larger than the forgone tax revenues estimated by JCT.

The combined subsidies will continue to grow as credit unions get bigger over time.

Credit Unions Subsidies Drive down Bank Rates—and Profits

Studies also show that competition from credit unions causes banks to reduce their interest rates and fees. As the authors of a study commissioned by the National Association of Federally-Insured Credit Unions (NAFCU) explain, “Consistent with basic microeconomic theory, increasing the number of firms in a market tends to lower prices offered by sellers; similarly, the increased availability of substitute goods provides competitive pressure.”[16] Thus, “the presence of credit unions not only helps members get better rates, but also serves as a check on the interest rates banks offer customers.”

The NAFCU study determined that the competition from credit unions caused banks to offer lower rates on loans and higher rates on deposits. From 2011 to 2020, the authors estimated the benefits of the rate differentials to bank customers totaled roughly $81 billion.[17]

This is, of course, one-column accounting, focusing on the benefits while ignoring the liabilities. What NAFCU calls benefits to customers are the revenues lost to banks. In other words, the taxpayer subsidies to credit unions cost banks more than $80 billion in reduced profits over a decade. Fewer profits mean less staffing, fewer services, and less tax revenues for the government.

Taxpayer Subsidies for Credit Unions Don’t Benefit Low-Income Customers

The Credit Union Membership Access Act reiterated that credit unions were granted their tax-exempt status “because they have the specified mission of meeting the credit and savings needs of consumers, especially those with modest means.”

No doubt this would be a noble mission, but as the Government Accountability Office has frequently lamented, there is no established definition of “modest means” nor has there been any sustained effort to measure how well credit unions are serving low- and modest-income customers.[18] GAO points out that none of the common-bond criteria to federally chartered credit unions refers to the economic status of their current or prospective members. Indeed, almost by default, the members of credit unions affiliated with large companies, universities, professional organizations, and even Congress tend to have above-average incomes.

NCUA produces no publicly available data on the economic standing of credit union members, so the job of estimating the reach of credit unions to low-income customers has been left to GAO, academics, and various surveys.

In a recent academic study, professors Pankaj K. Maskara and Florence Neymotin found that “unbanked” or “underbanked” households were less likely to be members of credit unions. Indeed, they found that credit union members are more likely to be “employed, high-education, and dual-income individuals.”[19]

To Maskara and Neymotin, the data suggests that “credit unions are not actually serving the needs of the underserved sector of society.” They surmise that the credit union sector “has grown to the size that it is simply incapable of serving the ‘underserved’ as the majority of its members.”

In a separate study, the same authors found that credit unions did little to provide consumers in troubled states liquidity in the form of home equity lines of credit during the financial crisis of 2008, contrary to their image as a lender for those in need.[20]

In an analysis of data from the 2019 Survey of Consumer Finance, Filene’s Center for Consumer Financial Lives in Transition found that credit union members tended to be more educated and older than bank customers and the general population.[21] Among credit union households, 66 percent had some college or a bachelor’s degree or higher compared to 24 percent of households overall.

Noting that the unbanked are most likely to have lower educational attainment than the banked population, the survey found that “credit unions serve a smaller share of members with no high school degree (6%) when compared to the overall population and bank households (11% each).”

On average, the survey found that bank primary households had a median income of $81,449, while credit union primary households had a median income of $74,801. However, a smaller share of credit union members were self-employed (9 percent) compared to bank customers (12 percent). The report noted that “[s]elf-employed individuals seem to prefer banks.”

In their analysis of the Survey of Consumer Finance, van Rijn et al. also found that bank customers had higher incomes and higher net worths than credit union customers. However, credit unions served more middle-income customers than banks, while banks served a greater share of customers at the lower end and upper end of the income scale.[22]

Prior studies by GAO found that the percentage of upper-income members of credit unions had been growing and that fewer credit union members were of “modest means” or low-income than bank customers. Using data from the 2004 Survey of Consumer Finance, GAO found that 14 percent of credit union customers were low-income compared to 24 percent for banks. Similarly, 31 percent of credit union members were of “modest-means” compared to 41 percent of bank customers. By contrast, nearly half (49 percent) of credit union customers were upper-income compared to 41 percent for banks.[23]

Credit Unions’ Continued Failure to Measure Service to the Underserved

As GAO reported in 2005, “While credit union fields of membership have expanded, the extent to which they serve people or communities of low or moderate incomes is not definitively known.”[24] Nothing has changed in the nearly two decades since GAO’s study because credit unions are still not required to collect and report this information.

More than 20 years ago, NCUA launched the Low-Income Credit Union (LICU) program to allow credit unions to expand their field of membership beyond what is limited by their common bond into “underserved” areas. For example, GAO discovered that a Maryland-based credit union was allowed to expand its service area to an “underserved” neighborhood in nearby Washington, D.C.

Today, more than half of all credit unions (2,585 out of 4,686) have been designated as “low-income” institutions, according to NCUA data.

This designation appears to be little more than a signaling device to allow credit unions (and NCUA) to claim they are serving underserved populations without having to provide any documentation to back it up. The NCUA website provides no data to prove that credit unions are in fact reaching the underserved.

A good example is the Congressional Federal Credit Union (CFCU), which was granted low-income status in 2022. Since 1953, CFCU’s membership has catered to members of Congress and their staff—hardly low-income customers.[25]

With its new low-income designation, CFCU’s service region[26] now spans a gerrymandered swath of Washington, D.C., from poor neighborhoods in the East and Southeast parts of the city to the campus of George Washington University (just a few blocks from the White House) and the White House itself. Yet, despite its service area containing low-income neighborhoods, CFCU does not operate any branches in poor areas.

The State Department Federal Credit Union (SDFCU) has also been designated as a low-income institution even though it primarily serves foreign service officers abroad.[27] There are, however, dozens of “Select Employee Groups” (SEGs) whose members can join the State Department credit union even though they seem to have no common bond with State Department employees.[28] This includes the employees of Alexandria Animal Hospital, the Broadcasting Board of Governors, the Greater Baltimore Board of Realtors, the Motley Fool, and the International Republican Institute, to mention a few.

Low-Income Designation Is a Boon to Credit Unions at the Expense of Banks

Economists Stefan Gissler, Rodney Ramcharan, and Edison Yu (Gissler et al.) studied how the low-income designation for credit unions impacted the credit market in the affected service areas.[29] The effects were bad for some banks, good for others, and mixed for consumers.

The study found that banks within a 5- or 10-mile radius of an increased number of low-income credit unions saw a “mirror decline in lending and deposit taking.” Bank failure rates increased in such areas, especially in states with higher taxes. This illustrates the role the tax exemption plays in allowing credit unions to out-compete local banks.

However, the competition in consumer lending from credit unions ironically made some banks more profitable as they shifted their business model away from consumer to business lending. But this also illustrates how the tax exemption allowed credit unions to encroach into the consumer lending market and take market share away from banks.

Gissler et al. did find that competition between credit unions and non-bank lenders drove each of them to increase the number of new loans they extended to borrowers in the “bottom half of the risk distribution.” Not surprisingly, however, their study also found that “this reallocation in automotive credit to riskier borrowers on account of increased competition is associated with a significant increase in non-performing loans.”[30]

It would be a mistake, however, to attribute the negative effects to competition per se because the “competition” is driven by distortion: taxpayer-subsidized credit unions pushing the lending market into riskier practices.

Credit Unions’ Vulnerable Business Model Necessitated the Relaxation of Common Bonds

Sponsors of the Credit Union Act of 1934 boasted that no credit unions failed following the financial crash of 1929, unlike hundreds of commercial banks. Whatever the reason for their survival then, the same could not be said for the fate of many credit unions during the double-dip recessions in the early 1980s. The economic downturns of the ‘80s exposed the vulnerability of the credit union business model to its narrow customer base.

In a law review article charting the legal battles between banks and credit unions, “Banks v. Credit Unions: The Turf Struggle for Consumers,” Kelly Culp reports that the narrow rules governing the common bond of credit unions almost became the industry’s undoing.[31]

According to Culp, the law required that federal credit union membership “be limited to groups having a common bond of occupation or association, or to groups within a well-defined neighborhood, community, or rural district.” For years, regulators interpreted the requirement narrowly to mean, for example, employees of a single company or soldiers at a particular military base.

As a result, Culp reports that by the 1980s, some 80 percent of credit unions were linked to specific employers, hundreds of which went bankrupt during the twin recessions. In 1981, 222 credit unions failed, which put a tremendous strain on the insurance fund supporting the industry.

Recognizing the vulnerability and uncertain viability of the credit union business model, the NCUA began to relax the common bond standards that tethered them to narrow customer bases.

In the years since, NCUA and Congress have relaxed the standards even further and allowed credit unions to create multiple common bonds that seemingly have no logic other than to permit credit unions to expand their customer base.

Credit Unions Are Using Taxpayer Subsidies to Buy Banks

Nothing illustrates more how credit unions have ditched their mission of serving the underserved than the growing efforts by credit unions to buy commercial banks. This trend also speaks to the cash credit unions can accumulate by being tax-exempt nonprofits and that not all of their profits accrue to the benefit of members.

Over the past decade, credit unions have purchased more than 80 banks, and a sizeable number of credit unions have purchased multiple banks.[32] Admittedly, 80 is not a large number of acquisitions compared to the hundreds of mergers between credit unions, or an even larger number of bank mergers during the period, but it still signals the ambitions of credit union managers to expand their membership, geographic footprint, and business lines. Some credit unions have purchased banks as a defensive measure to keep a rival from expanding into their geographic area.[33]

The trend toward bank purchases by credit unions also signals the limitations of the credit union business model. MarketWatch reports that the idea for the first credit union purchase of a bank in 2012 came out of a conversation between deal lawyer Michael M. Bell and one of his clients about the challenges of organic growth. “You have to scale,” he told MarketWatch. “It’s a fact of our economy [and] that’s happening in this industry. The small are disappearing and the big are getting bigger.”[34] The way credit unions are being encouraged to get bigger is by purchasing banks.

A recent example is the Michigan-based Dearborn Federal Credit Union (DFCU), which was approved by NCUA to purchase two Florida bank branches from MidWestOne Bank of Iowa City, Iowa. According to the Credit Union Times, DFCU “now has five branches in the Tampa area and one in St. Petersburg following its purchase of the Tampa-based First Citrus Bank in January.”[35] Nearly 25 percent of the Michigan-based DFCU’s branches are now in Florida.[36]

Another example is Lake Michigan Federal Credit Union, which has been expanding its reach into Florida since it opened a mortgage office in Bonita Springs in 2015.[37] Bonita Springs happens to be one of the wealthiest areas in Florida, with a median income of nearly $85,000 according to the U.S. Census Bureau. More than 80 percent of the community’s residents are White, and it has a very low poverty rate.

Since its 2015 expansion, Lake Michigan Federal Credit Union has purchased a number of commercial banks, including a 2021 purchase of Pilot Bancshares’ Pilot Bank and National Aircraft Finance Co., which specializes in financing aircraft.[38] Financing aircraft is quite a departure from the mission of serving underserved Michigan residents.

Credit unions are ideal buyers, say experts, because they tend to be all-cash buyers, whereas commercial buyers prefer to use stock or equity for the deal. Since many community banks are family-owned or have a modest number of shareholders, they prefer the cash deal. And credit unions tend to offer a higher price for the purchase because they don’t have to worry about the tax implications.

But states and the federal government should worry about the tax implications. The transactions are unique in that the credit unions are purchasing the assets of the bank, but not the charter. Thus the assets become part of the nonprofit credit union while what is left of the taxpaying bank is effectively dissolved. While the revenue losses might not be large for state and federal treasuries, they are still a troubling consequence of allowing such deals.

Even within the credit union industry, complaints arise that the terms of the deals are rarely made public and that members are not informed why their capital is being used to purchase a bank rather than returned to members. Frank J. Diekmann, co-founder of CUToday.info, also says members ought to know if CEOs—whose contracts often tie their compensation to asset size—are getting raises out of the deals. “Members have a right to know about that,” he writes, “especially since—again—it’s their money being used to goose the comp.”[39]

Diekmann reminds readers that commercial bank buyers would have to report such information to shareholders, so why are there different standards for credit unions?

Is There Still a Need for Credit Unions?

When President Roosevelt signed the Credit Union Act of 1934, only about 40 percent of U.S. households had a telephone. Phones were considered a luxury. Today, nearly half (48.8 percent) of underbanked households use mobile banking as their primary method of accessing their bank account. According to the 2021 FDIC National Survey of Unbanked and Underbanked Households, the rate of mobile banking for the underbanked is greater than among fully banked households (42.5 percent).[40]

More than telephone access has changed since credit unions were thought to be a salvation for the poor and working class. Nearly every American has access to banking today thanks to technology and financial innovation.

The FDIC survey reports that the percentage of unbanked households has declined considerably since 2009, the first year of the study. In 2021, the unbanked rate stood at 4.5 percent of households (approximately 5.9 million), the lowest rate since 2009 and a 3.7 percentage point drop since 2011—the last peak. This corresponds to an increase of 5 million banked households over a decade and means that more than 95 percent of households are now banked.

That said, the rates of the unbanked tend to be higher among lower-income, less-educated, Black, and Hispanic households, according to FDIC. Interestingly, entrepreneurs are stepping up to reach underserved minority markets, which is another sign that credit unions have failed to meet the needs of these groups.

For example, MoCaFi.com is a Black-owned online bank focused on the Black community. Majority.com offers all-in-one mobile banking for migrants. The mobile app “en.Comun.app” is focused on serving the Latino community. Finally, myTotem.app is an app aimed at serving the Native American community.

Online and mobile banking—which most banks and credit unions now offer—completely removes the need for a common bond or location-specific membership requirements. Indeed, the notions of “field of membership” and “common bond” are anachronistic in today’s digital economy.

No one who has a computer or cellphone can be considered “underserved.” PenFed, the nation’s third-largest credit union, has a rare “open charter,” which means there are no restrictions on its membership. As a result, PenFed can draw customers from a national market. Thus, it is fair to say that there are no “underserved” markets in the U.S., except for those people who can’t access PenFed’s website.

To be sure, there will always be people who are “unbanked” because—as the FDIC survey indicates—they “don’t trust banks,” are unemployed, are undocumented workers, or don’t think they have enough money to meet the minimum requirements for an account. But thanks to technology and modern innovations in financial services, it is safe to say that nearly every American now has access to banking services, thus fulfilling the original impetus for creating credit unions in 1934.

Conclusion

Credit unions’ privileged status as tax-exempt nonprofit organizations may have filled a market need during the Great Depression, but 90 years later, there is no longer a justification to subsidize these institutions. Credit unions no longer serve the underserved. Their true taxpayer subsidy is many times the estimated forgone tax revenues. And their relaxed common bonds and expanded product offerings are a telling indication that their original business model is not viable and that they must be more like banks to survive.

This is not the first time that lawmakers have had to address unfair competition in financial markets. In 1951, lawmakers repealed the tax exemption for mutual savings banks and savings and loan associations, which were created to help low-income working customers, “in order to establish parity between competing financial institutions.”

The Senate report accompanying the Revenue Act of 1951 highlighted how mutual savings banks actively competed with “commercial banks and life insurance companies for the public savings, and they compete[d] with many types of taxable institutions in the security and real estate markets.”[41] Their tax-exempt status gave these institutions “the advantage of being able to finance growth out of untaxed retained earnings,” unlike competing commercial banks who must pay tax on their retained income. Thus, the report concluded, continuing the “tax-free treatment now accorded mutual savings banks would be discriminatory.”

What was true for mutual savings banks in 1951 is true for credit unions today. Fairness, equity, and public finance demand that credit unions be put on the same tax footing as the commercial banks they compete with. Considering the country’s $34 trillion national debt, subsidizing credit unions is a luxury taxpayers can no longer afford.

[1] John T. Croteau, “The Federal Credit Union System: A Legislative History,” Social Security Bulletin 19:5 (May 1956): 10. https://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/ssb/v19n5/v19n5p10.pdf.

[2] 73 Cong. Rec. H12225 (1934), https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/GPO-CRECB-1934-pt11-v78/pdf/GPO-CRECB-1934-pt11-v78-3-2.pdf.

[3] Erdis W. Smith, “Federal Credit Unions,” Social Security Bulletin 11:10 (October 1948): 4, https://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/ssb/v11n10/v11n10p13.pdf#nameddest=article.

[4] 73 Cong. Rec. H12223 (1934).

[5] Erdis W. Smith, “Federal Credit Unions: Origin and Development,” Social Security Bulletin 18:11 (November 1955): 3, https://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/ssb/v18n11/v18n11p3.pdf.

[6] National Credit Union Administration, “Quarterly Data Summary Reports,” December 2022, https://ncua.gov/files/publications/analysis/quarterly-data-summary-2022-Q4.pdf.

[7] Credit Union Membership Access Act, Pub. L. No. 105-219 (1998), https://www.congress.gov/bill/105th-congress/house-bill/1151/text.

[8] U.S. Government Accountability Office, “Credit Unions: Greater Transparency Needed on Who Credit Unions Serve and on Senior Executive Compensation Arrangements,” GAO-07-29, Nov. 30, 2006, https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-07-29.

[9] NCUA, “5300 Call Report Aggregate Financial Performance Reports (FPRs),” December 2019, https://ncua.gov/files/publications/analysis/financial-performance-aggregate-report-dec-2019.zip.

[10] NCUA, “5300 Call Report Aggregate Financial Performance Reports (FPRs),” December 2022, https://ncua.gov/files/publications/analysis/financial-performance-aggregate-report-dec-2022.zip.

[11] Thomas G. Noland and Edward H. Sibbald, “100 Years of Credit Unions: Impact of Tax Exempt Status The Case for Georgia,” Southern Business Review 35:1 (January 2010): 1-14, https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1117&context=sbr.

[12] Jordan van Rijn, Shuwei Zeng, and Paul Hellman, “Financial Institution Objectives & Auto Loan Pricing: Evidence from the Survey of Consumer Finance,” https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3520630.

[13] Don Fullerton, “Tax Policy Toward Art Museums,” National Bureau of Economic Research, June 1990, https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w3379/w3379.pdf; see also: https://intranet.americansforthearts.org/by-program/reports-and-data/legislation-policy/naappd/tax-policy-toward-art-museums.

[14] Robert DeYoung, John Goddard, Donal G. McKillop, John O.S. Wilson, “Who Consumes Credit Unions Subsidies?,” QMS Research Paper, May 10, 2022, https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/271258/1/qms-rp2022-03.pdf.

[15] Credit Union National Association, “U.S. Membership Benefits Report Mid-Year 2023,” https://www.cuna.org/content/dam/cuna/advocacy/cu-economics-and-data/credit-union-snapshot/National-MemberBenefits.pdf

[16] Robert M. Feinberg and Douglas Meade, “Economic Benefits of the Credit Union Tax Exemption to Consumers, Businesses, and the U.S. Economy,” National Association of Federally-Insured Credit Unions,” September 2021, https://www.nafcu.org/system/files/files/NAFCU%202021%20CU%20Tax%20Study-FULL-Web.pdf.

[17] Id.

[18] GAO, “Credit Unions: Greater Transparency Needed.”

[19] Pankaj K. Maskara and Florence Neymotin, “Do Credit Unions Serve the Underserved,” Eastern Economic Journal 47:4 (January 2021): 184-205, https://link.springer.com/article/10.1057/s41302-020-00183-3.

[20] Pankaj K. Maskara and Florence Neymotin, “Credit Unions During the Crisis: Did They Provide Liquidity?,” Applied Economic Letters 26:3 (May 2019): 174-179, https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3353559.

[21] Salma Mohammad Ali, “Who Uses Credit Unions? Fifth Edition,” Center for Consumer Financial Lives in Transition, Mar. 31, 2021, https://www.filene.org/reports/who-uses-credit-unions-fifth-edition.

[22] Jordan van Rijn et al., “Financial Institution Objectives & Auto Loan Pricing.”

[23] GAO, “Credit Unions: Greater Transparency Needed.”

[24] Government Accountability Office, “Financial Institutions: Issues Regarding the Tax-Exempt Status of Credit Unions,” GAO-06-220T, Nov. 3, 2005, https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-06-220t.

[25] Congressional Federal Credit Union, https://www.congressionalfcu.org/.

[26] CFCU Service Region Map, https://www.congressionalfcu.org/images/default-source/default-album/mapfb4bf3ecffa460b09f66ff3800d28eef.jpg.

[27] State Department Federal Credit Union, https://www.sdfcu.org/.

[28] SDFCU.org, “Organizational, Association, Company and Group Affiliations (Select Employee Groups),” https://www.congressionalfcu.org/images/default-source/default-album/mapfb4bf3ecffa460b09f66ff3800d28eef.jpg.

[29] Stefan Gissler, Rodney Ramcharan & Edison Yu, “The Effects of Competition in Consumer Credit Market,” National Bureau of Economic Research, August 2019, https://www.nber.org/papers/w26183.

[30] Gissler et al., “The Effects of Competition in Consumer Credit Market.”

[31] Kelly Culp, “Banks v. Credit Unions: The Turf Struggle for Consumers,” The Business Lawyer 53:1 (November 1997): 193-216, https://www.jstor.org/stable/40687781.

[32] Lauren Seay and Ronamil Portes, “Credit unions launch bank buying spree with 5 deals in 1 week,” S&P Global Market Intelligence, Sep. 5, 2023, https://www.spglobal.com/marketintelligence/en/news-insights/latest-news-headlines/credit-unions-launch-bank-buying-spree-with-5-deals-in-1-week-77281711.

[33] Wilary Winn, “Credit Unions Purchasing Community Banks,” https://wilwinn.com/resource/credit-unions-purchasing-community-banks/.

[34] Steve Gelsi, “Credit Unions buying banks? Yes indeed, says this deal lawyer,” MarketWatch, Aug. 12, 2022, https://www.marketwatch.com/story/credit-unions-buying-banks-yes-indeed-says-this-deal-lawyer-11660304804.

[35] Jim DuPlessis, “Detroit Credit Union Motors South,” Credit Union Times, Mar. 17, 2023, https://www.cutimes.com/2023/03/17/detroit-credit-union-motors-south/.

[36] Jim DuPlessis, “Michigan CU Bank Buy Deal Would Place Nearly 25% of Its Branches in Florida,” Credit Union Times, Sep. 27, 2023, https://www.cutimes.com/2023/09/27/michigan-cu-bank-buy-deal-would-place-nearly-25-of-its-branches-in-florida/.

[37] Mark Sanchez, “Lake Michigan Credit Union continues Florida expansion with planned acquisition,” Crain’s Grand Rapids Business, Jun. 16, 2021. https://www.crainsgrandrapids.com/news/banking-finance/lake-michigan-credit-union-continues-florida-expansion-with-planned-acquisition/.

[38] Ibid.

[39] Frank J. Diekmann, “Why NCUA Should Require CUs to Disclose What They’re Paying for Banks,” CUToday.info, Sep. 20, 2023, https://www.cutoday.info/THE-tude/Why-NCUA-Should-Require-CUs-to-Disclose-What-They-re-Paying-for-Banks.

[40] FDIC, “2021 FDIC National Survey of Unbanked and Underbanked Households,” Jul. 24, 2023, https://www.fdic.gov/analysis/household-survey/index.html.

[41] United States Senate, “The Revenue Act of 1951: Report of the Committee on Finance to Accompany H.R. 4473 a Bill to Provide Revenue, and for Other Purposes,” Sep. 18, 1951, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/SERIALSET-11489_00_00-137-0781-0000/pdf/SERIALSET-11489_00_00-137-0781-0000.pdf.

Share this article