Oregon voters will weigh in on taxation of tobacco and nicotine products next month. If voters pass Measure 108, the Tobacco and E-Cigarette Tax Increase for Health Programs Measure, it would increase taxes on cigarettes and cigars and introduce a new taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. on vapor products beginning January 2021. The measure was passed by the Oregon legislature in July but is subject to voter approval.

The measure would increase the excise taxAn excise tax is a tax imposed on a specific good or activity. Excise taxes are commonly levied on cigarettes, alcoholic beverages, soda, gasoline, insurance premiums, amusement activities, and betting, and typically make up a relatively small and volatile portion of state and local and, to a lesser extent, federal tax collections. on cigarettes by 10 cents per cigarette ($2 per pack), resulting in a new tax rate of $3.33 per pack (not including the federal rate of $1.0066 per pack). According to the Oregon Legislative Revenue Office, this increase will raise $108.7 million for the remainder of this biennium (2019-21), $324.0 million in 2021-23, and $323.1 in 2023-25.

In addition to the increased tax on cigarettes, the measure includes a new tax on vapor products. Vapor products would be taxed at 65 percent (levied on both devices and liquid) of wholesale value, and would raise $6.0 million in 2019-21, $25.1 million in 2021-23, and $26.6. million in 2023-25. Finally, the measure includes an increase to the tax cap on cigars (from 50 cents to $1 per cigar). This increase is forecast to raise $300,000 in this biennium, $1.3 million in 2021-23, and $1.4 million in 2023-25.

Excise taxes on tobacco products are legitimate because these products cause negative externalities. For instance, some health-care costs of smoking are covered by government, and secondhand smoke affects nonsmokers. Levying an excise tax allows a state to recover the costs related to these externalities—thereby internalizing them. However, while these taxes can be legitimate, they should be carefully designed. Unfortunately, Measure 108 contains numerous design flaws.

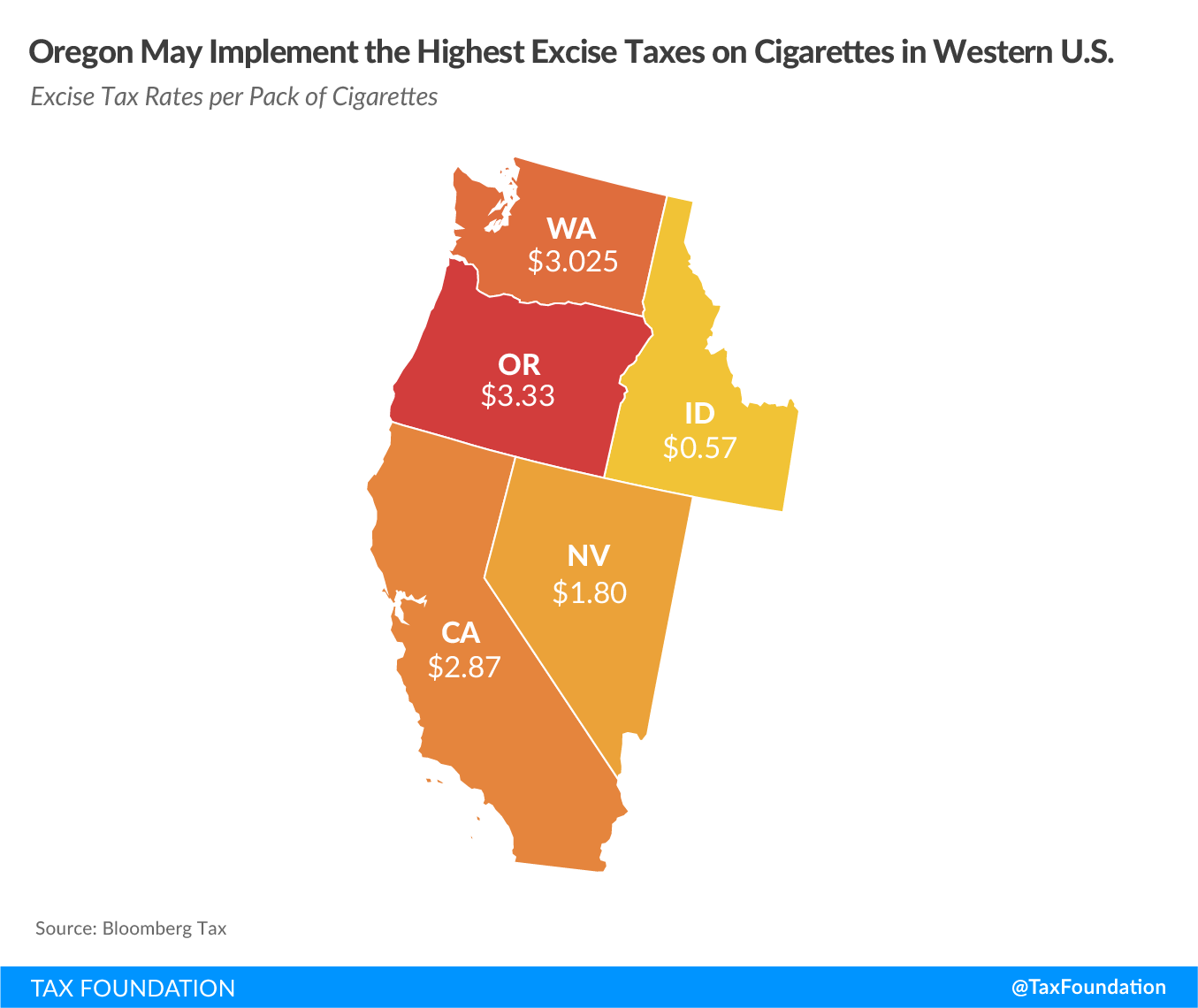

Increasing excise taxes on cigarettes by $2 is a significant, and highly regressive, tax increase on the state’s smokers. In 2019, smokers already paid close to $200 million in excise taxes. The measure introduces a risk of increased tax avoidance and evasion activity as consumers of the products often procure cigarettes from lower tax jurisdictions. At $3.33 per pack, Oregon would have the highest excise tax on cigarettes in the region. Tax avoidance not only harms revenue, it also harms local businesses relying on tobacco consumers. The increased rate would also apply to potentially harm-reducing heated tobacco products due to the tax definition.

Measure 108 would tax vapor products based on price (ad valorem). Vapor products with similar qualities and in similar quantities should have equal tax liability regardless of design or price, a principle ad valorem taxes ignore. Ad valorem taxes also incentivize downtrading, which is when consumers move from premium products to cheaper alternatives. Downtrading effects do not reduce harm and have no relation to any externality the tax is seeking to capture.

A superior design would be a tax based on volume, as volume is a better proxy for the harm associated with consumption (the negative externalityAn externality, in economic terms, is a side effect or consequence of an activity that is not reflected in the cost of that activity, and not primarily borne by those directly involved in said activity. Externalities can be caused by either the production or consumption of a good or service and can be positive or negative. ). In addition to capturing the externality, it is the administratively simplest and most straightforward way for governments to tax a good as it does not require valuation and as such does not require expensive tax administration. For instance, in vertically integrated companies (some vape shops both manufacture and retail vapor liquid), taxable value must be computed to estimate tax liability. Taxing based on quantity rather than value makes it easier for governments to forecast revenue as it is not affected by changes in consumer brand preference or retail prices. Simple taxes lower compliance costs and make it easier for tax authorities to enforce the tax.

In addition to a non-neutral base, Measure 108 includes a rather high rate at 65 percent (fourth highest nationwide). To encourage harm reduction (consumers switching from more harmful cigarettes to less harmful vapor products), the products should be taxed relative to harm. Thus, excise taxes on vapor products should be relatively low compared to those on combustible tobacco products as cigarettes and vapor products are economic substitutes, which means that increased prices on either may encourage consumers to switch to the other.

Measure 108 would levy the tobacco products tax of 65 percent on vapor products rather than creating a separate tax category, which could have allowed for tax differentiation based on harm profile. To further enhance the harm reduction element, Oregon lawmakers could consider including a Modified Risk Tobacco Product (MRTP) provision. Five states already have provisions in their tax code that automatically lower the tax rate for products designated as MRTPs by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

While high cigarette tax rates may increase tax avoidance, there is a provision in the vapor tax proposal that may create avoidance issues of its own. In the definition of vapor products, Measure 108 exempts vapor products intended solely for use with marijuana. The problem arises because the devices capable of vaporizing liquid containing THC are perfectly capable of also vaporizing nicotine. Enforcement of this particular provision will be nearly impossible.

If the measure were enacted, 90 percent of the additional revenue from the increased taxes would be dedicated to the Oregon Health Authority for funding the maintenance and expansion of people eligible for medical assistance, and 10 percent would be dedicated to tribal health providers, Urban Indian Health programs, regional health equity coalitions, culturally specific and community-specific health programs, and state and local public health programs .

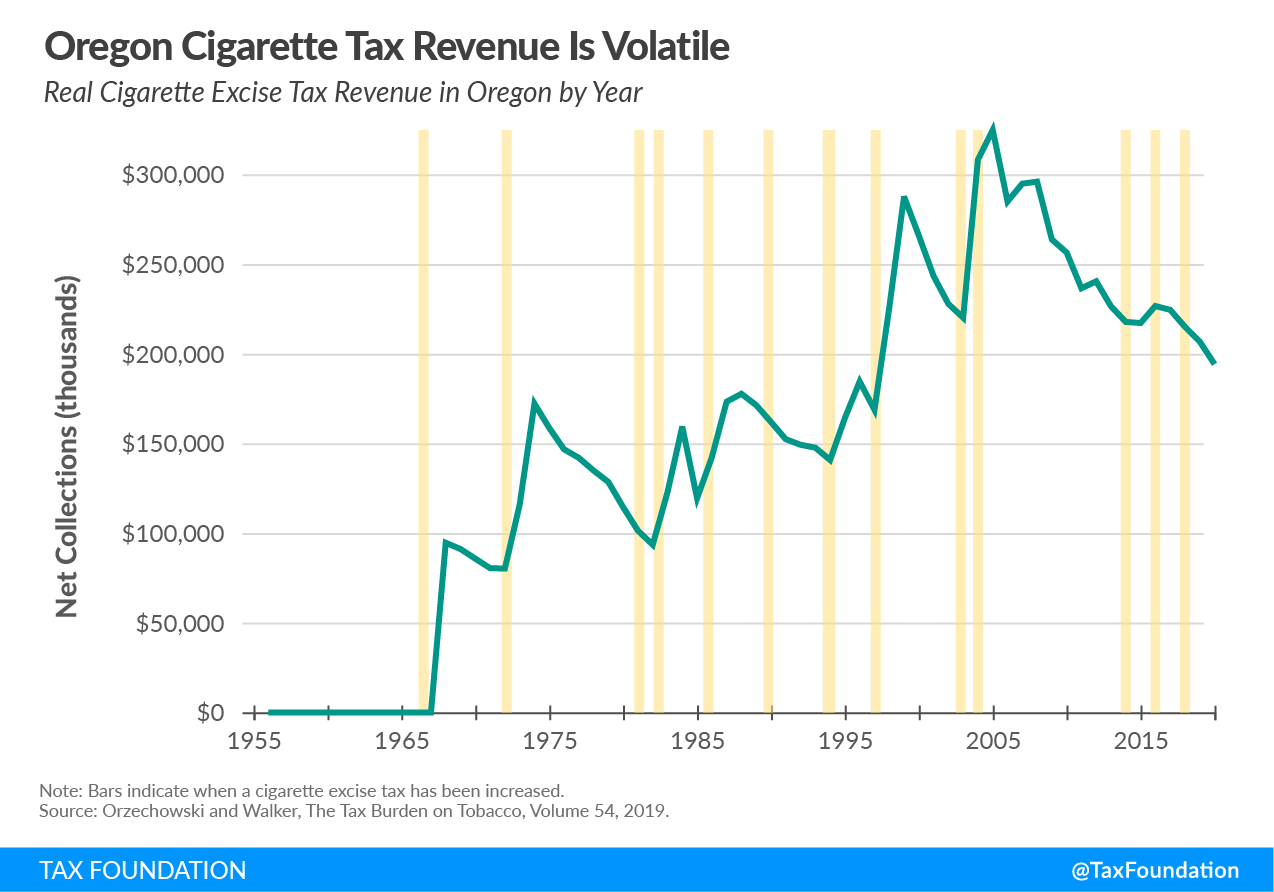

While the appropriations in Measure 108 are, in some ways, related to the externalities associated with tobacco consumption, they are not targeted at smoking-related health concerns. That raises a big issue: health-care costs are likely to increase in the coming years, whereas tobacco consumption and, consequently, tobacco tax revenue is highly likely to decline. Relying on tobacco consumption to cover general health-care spending will eventually prove unsustainable. Given excise taxes’ narrow design and volatility, they are not reliable for recurring unrelated spending priorities. Oregon lawmakers should expect that revenue from the tax increase will, after a short bump, decline over time as fewer people are likely to smoke in the future. Ultimately, Measure 108 contains significant narrow tax increases that do not capture the negative externalities related to consumption but instead increase the risk of downtrading and tax avoidance.

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

Subscribe