Key Findings

-

Trade barriers such as tariffs raise prices and reduce available quantities of goods and services for U.S. businesses and consumers, which results in lower income, reduced employment, and lower economic output.

-

Measures of trade flows, such as the trade balance, are accounting identities and should not be misunderstood to be indicators of economic health. Production and exchange – regardless of the balance on the current account – generate wealth.

-

Since the end of World War II, the world has largely moved away from protectionist trade policies toward a rules-based, open trading system. Post-war trade liberalization has led to widespread benefits, including higher income levels, lower prices, and greater consumer choice.

-

Openness to trade and investment has substantially contributed to U.S. growth, but the U.S. still maintains duties against several categories of goods. The highest tariffs are concentrated on agriculture, textiles, and footwear.

-

The Trump administration has enacted tariffs on imported solar panels, washing machines, steel, and aluminum, plans to impose tariffs on Chinese imports, and is investigating further tariffs on Chinese imports and automobile imports.

-

The effects of each tariffTariffs are taxes imposed by one country on goods imported from another country. Tariffs are trade barriers that raise prices, reduce available quantities of goods and services for US businesses and consumers, and create an economic burden on foreign exporters. will be lower GDP, wages, and employment in the long run. The tariffs will also make the U.S. tax code less progressive because the increased taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. burden would fall hardest on lower- and middle-income households.

-

Rather than erect barriers to trade that will have negative economic consequences, policymakers should promote free trade and the economic benefits it brings.

Introduction

Trade barriers, such as tariffs, have been demonstrated to cause more economic harm than benefit; they raise prices and reduce availability of goods and services, thus resulting, on net, in lower income, reduced employment, and lower economic output.

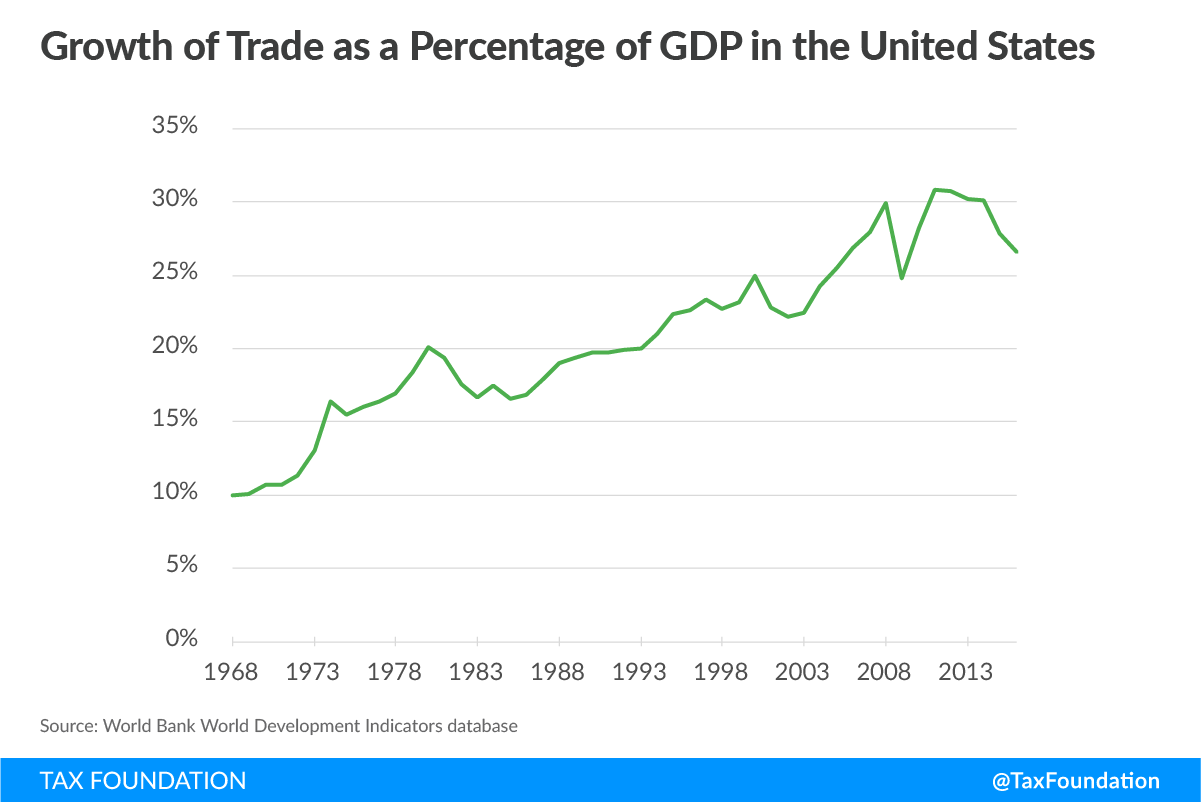

Since the end of World War II, the world has largely moved away from protectionist trade policies toward a rules-based, open trading system. This widespread reduction in trade barriers has contributed to economic prosperity in many ways, including large increases in trade activity and accompanying gains in economic output and income.

Openness to trade and investment has substantially contributed to U.S. growth, but the U.S. still maintains duties against several categories of goods. The overall effective rate of these tariffs appears low, but varies widely across categories of goods. Some of the highest duties apply to clothing, apparel, and footwear; some of the lowest apply to aircrafts, spacecrafts, and live animals.

This paper provides a brief overview of tariffs, the basic economics of trade and barriers to trade, and explains why the trade balance shouldn’t be viewed as an indicator of economic health. Then the paper reviews the current United States Harmonized Tariff Schedule and recent developments in United States tariff policies.

Overview of Tariffs

Tariffs are a type of excise taxAn excise tax is a tax imposed on a specific good or activity. Excise taxes are commonly levied on cigarettes, alcoholic beverages, soda, gasoline, insurance premiums, amusement activities, and betting, and typically make up a relatively small and volatile portion of state and local and, to a lesser extent, federal tax collections. that is levied on goods produced abroad at the time of import. They are intended to increase consumption of goods manufactured at home by increasing the price of foreign-produced goods. [1]

Generally, tariffs result in consumers paying more for goods than they would have otherwise in order to prop up industries at home. Though tariffs may afford some short-term protection for domestic industries that produce the goods subject to tariffs by shielding competition, they do so at the expense of others in the economy, including consumers and other industries.[2]

As consumers spend more on goods on which the duty is imposed, they have less to spend on other goods—so, one industry is propped up to the disadvantage of all others. This results in a less efficient allocation of resources, which can then result in slower economic growth. Tariffs also tend to be regressive in nature, burdening lower-income consumers the most.

Trade and the economy

Trade makes a nation wealthy, and conversely, trade restrictions make a nation poorer.[3]

Trade enables nations to specialize in activities in which they have a comparative advantage; in other words, what they can produce at a relatively lower opportunity cost, and trade for what they would otherwise have to produce at a higher opportunity cost.[4] This means nations produce more goods and services for less and exchange those for goods and services from other countries, resulting in higher levels of consumption than would be possible without trade.

Through this process, productivity increases as resources flow to the economic activities in which a country has a comparative advantage.[5] This leads to employment gains where production is most efficient, though it can also lead to employment losses in sectors where production is comparatively less efficient—an outcome of which policymakers should remain cognizant. On net, though, trade results in higher levels of productivity, income, and output throughout the economy. And over time, increased trade has made the United States more productive and has contributed to large increases in Americans’ standard of living.[6]

Since the end of World War II, growth in annual real global trade has outpaced GDP growth, growing on average 1.5 times faster.[7] Much of this increase in trade can be explained by reductions in barriers to international exchange, such as tariffs and quotas.[8] Post-war trade liberalization has led to widespread benefits, including higher income levels, lower prices, and greater consumer choice.[9]

Estimates of these post-war gains from freer trade range up to $10,000 per household in the United States.[10] The positive, long-term economic effects of trade – increased competition, innovation, productivity, employment, wages, and output – provide benefits that outweigh the short-term transition costs trade can cause.

But what about trade balances?

Trade clearly results in positive economic outcomes, allowing people in different countries to specialize in what they do best, and then exchange physical goods, services, and financial assets across borders. But there are often misperceptions about the measurements that economists and policymakers use to track flows of trade.

The balance-of-payments system consists of the current account, which measures the flow of goods and services, and the capital account, which records the flow of finances.[11] Walking through an example of a business that imports and exports is useful to understand how the balance-of-payments system works.[12]

Suppose an American business loads $100 million worth of goods it produced onto a cargo ship. When the ship leaves the country, it is credited to the current account as an export of $100 million. Now suppose that the business sells the goods to France; after shipping and other costs, the business makes a 20 percent profit selling to French customers.

The business now has $120 million it can use to make purchases in France. Suppose they decide to purchase wine, load it back on the now-empty cargo ship, and return to the United States; the value of the imported wine ($120 million) is debited from the current account. The business now sells the wine to its American customers, making another $10 million in profit. The business has made $20 million from the original sell of the goods in the cargo ship, and another $10 million from selling the imported wine, for a net profit of $30 million.

According to the current accounts, America has exported $100 million to France and imported $120 million from France—resulting in a so-called trade deficit of $20 million. But, we can see that the American business is clearly better off by having made these exchanges, $30 million better off.

Suppose in the next month, the American business sends another cargo ship to France with another $100 million worth of goods. But unfortunately, the entire ship sinks before it reaches France, leaving the business at a total loss. The $100 million export was credited to the current account; because there is no corresponding import, the national accounts show a trade surplus of $100 million. We can agree that no one has been made better off here, even though the accounting identity shows a trade surplus.

The capital account is also involved in these transactions, recording the exchange of financial assets, like currency. When the U.S. business buys wine from France, they give U.S. dollars in exchange for that wine—this is credited to the capital account. Conversely, when the U.S. business sold goods to France in exchange for Euros, this was debited to the capital account. Thus, in the example above, the capital account had a $20 million surplus. This indicates that foreigners have U.S. dollars that, at some point in the future, will be reinvested into the United States. In other words, when we spend dollars on foreign goods, those dollars do not disappear; they will return to the U.S. as a capital inflow at some time in the future.

The balance-of-payments system is simply an accounting identity; the current and capital accounts track flows of goods, services, and financial assets between people, and they move in the opposite direction of one another. A current account (trade) deficit is simply another way of stating that we have a capital account surplus; neither has a causal implication for the health of the economy. Whether a business sells to or buys from domestic or foreign consumers, they do so because the trade is profitable. Production and exchange – regardless of the balance on the current account – generate wealth.

Barriers to trade reduce economic output and incomes

When countries erect barriers to trade, such as tariffs, they raise prices and divert resources away from relatively efficient economic activities towards less efficient economic activities.[13] It is worth noting that in addition to tariffs, many other policy measures can create barriers to trade that have effects like tariffs.[14] As a result of such measures, consumers pay more for goods than they otherwise would have, businesses face higher costs than they otherwise would have, and on net, output and employment fall.

Tariffs in particular can have this effect through a few channels. One possibility is that a tariff may be passed on to producers and consumers in the form of higher prices. Tariffs can raise the cost of intermediate goods such as parts and materials, which then raises the price of goods that use those inputs and reduces private sector output.[15], [16] This would result in lower incomes for both workers and the owners of capital. Similarly, higher consumer prices due to tariffs would reduce the after-tax value of both labor and capital income. Because these higher prices would reduce the return to labor and capital, they would incentivize Americans to work and invest less, leading to lower output.[17]

Alternatively, the U.S. dollar may appreciate in response to tariffs, offsetting the potential price increase on U.S. consumers.[18] However, the more valuable dollar would make it more difficult for exporters to sell their goods on the global market, resulting in lower revenues for exporters. This would also result in lower U.S. output and incomes for both workers and owners of capital, reducing incentives for work and investment, and leading to a smaller economy.

Academic studies have quantified the costs of tariffs and shown that tariffs often fail to achieve their objectives.[19] A comprehensive study of tariffs in place in 1990 found that the annual consumer costs per American job “saved” range from $100,000 to over $1 million, with an average of $170,000.[20] More recently, a study analyzing the 2002 steel tariffs imposed by the George W. Bush administration found that the first year the tariffs were in effect, more American workers lost their jobs due to higher steel prices (200,000) than the total number employed by the steel industry itself at the time (187,500).[21]

These results aren’t unique to the 2002 steel tariffs. A Congressional Budget Office report from 1986 reviewed the effects of protectionist policies covering textiles and apparel, steel, footwear, and automobiles. The policies did effectively increase costs, which resulted in slightly higher profits for the firms. However, the report finds, “In none of the cases studied was protection sufficient to revitalize the affected industry.”[22]

The outcomes of past protectionist policies indicate that protectionism simply does not work. Any potential short-term benefits of using protectionist policies to shield domestic industries from foreign competition come at the expense of others in the economy; the consequences are higher prices, less efficient resource allocation, and job losses throughout other sectors, and in the long run, failure to help the intended beneficiaries.

The United States Maintains a Wide Variety of Tariffs

While global trade restrictions have dramatically fallen over the past several decades, the United States still maintains many tariffs on a wide variety of goods. The United States International Trade Commission (USITC) publishes the Harmonized Tariff Schedule, which contains 99 chapters describing various tariffs that apply to different categories of goods.[23] The USITC also maintains a tariff database, reporting statistics that include the value of imports appraised by the U.S. Customs Service as well as estimates of the calculated duties by commodity.

A superficial glance at the database might convey the idea that tariffs are relatively small. For example, in 2017, the total value of imports was $2.3 trillion and the total estimated duties were $33.1 billion, implying an overall average tariff of about 1.42 percent.[24] Though the average U.S. tariff looks small, some individual categories of goods are subject to much higher import barriers.

In 2017, for example, the United States imported $109.5 billion worth of textiles and textile articles, and paid $12.6 billion in tariffs on these imports, or an average applied tariff of 11.5 percent.[25] Within this category of imported goods, some subcategories faced even higher tax burdens. The rate on knitted or crocheted apparel and clothing accessories was above 14 percent in 2017.[26]

Browsing the Harmonized Tariff Schedule shows that in some cases, even higher rates may apply. The maximum rate of duty that applies to “Men’s or boy’s overcoats, carcoats, capes, cloaks, anoraks (including ski jackets), windbreakers and similar articles, knitted or crocheted – Other” is 72 percent.[27] The most recent World Trade Organization Policy Review of the United States found that:[28]

Tariffs above 25% ad valorem are concentrated in agriculture (notably dairy, tobacco, and vegetable products), footwear, and textiles. An estimated 22 tariff lines corresponding to agricultural products carry import duty rates above 100%.

| Source: United States International Trade Commission, “Interactive Tariff and Trade DataWeb,” https://dataweb.usitc.gov/ | |||

| Section | Customs Value | Calculated Duty | Average Applied Rate |

|---|---|---|---|

|

XI: Textiles and Textile Articles |

$109.5 | $12.6 | 11.53% |

|

VIII: Raw Hides and Skins, Leather, Furskins and Articles Thereof; Saddlery and Harness; Travel Goods, Handbags and Similar Containers; Articles of Animal Gut (Other Than Silkworm Gut) |

13.8 | 1.4 | 10.20% |

|

XII: Footwear, Headgear, Umbrellas, Sun Umbrellas, Walking Sticks, Seatsticks, Whips, Riding-Crops and Parts Thereof; Prepared Feathers and Articles Made Therewith; Artificial Flowers; Articles of Human Hair |

30.7 | 3.1 | 10.09% |

|

All Sections |

2,313.0 | 33.1 | 1.42% |

In addition to causing economic harm for the reasons discussed above, tariffs generally have nonneutral impacts across different goods and different sectors, and this nonneutrality can further reduce welfare. Uneven tax burdens may distort investment decisions, adding complexity that penalizes certain goods worse than others and thus negatively impacting economic growth. Though tariffs generated a relatively small amount of revenue in 2017, $33.1 billion, high rates concentrated on certain categories of imports creates distortions in the economy.

Tariffs and the Trump Administration

Within the first few months of 2018, the Trump administration enacted tariffs on imported solar panels, washing machines, steel, and aluminum.[29] The administration plans to soon impose a 25 percent tariff on $50 billion worth of Chinese imports.[30] In addition to these planned tariffs, pending investigations regarding further tariffs on up to $100 billion more worth of Chinese imports as well as automobile imports mean more tariffs could be imposed going forward.[31]

The rationale for these various tariffs range from national security to misconceptions about trade balances to alleged intellectual property theft by China. Though there is wide agreement that certain trading practices are unfair and call for a response, levying broad tariffs is not likely the approach that will result in the desired policy changes.[32] The effects of each tariff will be lower GDP, wages, and employment in the long run.[33]

For example, according to the Tax Foundation’s Taxes and Growth model, President Trump’s proposal to raise taxes by approximately $37.5 billion annually (by levying a 25 percent tariff on $150 billion worth of Chinese imports) would reduce the long-run level of GDP by 0.1 percent, or about $20 billion.[34] The smaller economy would result in 0.1 percent lower wages and 79,000 fewer full-time equivalent jobs. The tariffs will also make the U.S. tax code less progressive because the increased tax burden would fall hardest on lower- and middle-income households.[35]

| Source: Tax Foundation Taxes and Growth Model, March 2018 | |

| Change in long-run GDP | -0.1% |

| Change in long-run GDP (Billions $2018) | -$20.6 |

| Change in long-run wage rate | -0.1% |

| Change in full-time equivalent jobs | -79,000 |

These estimates do not account for the uneven impact these taxes would have across sectors, nor the costs of retaliatory actions that have already been imposed and may be proposed in the future. These effects would both result in worse economic outcomes.

Conclusion

Since the end of World War II, public policy has shifted to embrace free and open trade, and reduced many trade barriers. This increase in international trading activity has led to increases in productivity, employment, output, and incomes for the countries involved.

Though historically the United States has led the movement toward free and open trade, the U.S. maintains high tariffs on select categories of goods. These sectors of the economy are not open to free trade or the competitive pressures free trade entails, and the related prices are artificially raised because of tariffs and other restrictions. Rather than focus trade policy on reducing these barriers, recent actions by the Trump administration have been to levy new tariffs and threaten further trade restrictions.

History has shown that tariffs fail to achieve their intended objectives, and result in higher prices, lower employment, and slower economic growth in the long run. Rather than erect barriers to trade that will have negative economic consequences, policymakers should promote free trade and the economic benefits it brings.

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

Subscribe

Notes

[1] Jagdish Bhagwati, “Protectionism,” in David R. Henderson, ed., The Concise Encyclopedia of Economics (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund Inc., 2002), www.econlib.org/library/Enc/Protectionism.html.

[2] Adam Smith, “Of Restraints upon the Importation from Foreign Countries of such Goods as can be Produced at Home,” in An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, Book IV, Chapter II, www.econlib.org/library/Smith/smWN13.html#B.IV.

[3] James K. Glassman, “The Blessings of Free Trade,” Cato Institute, May 1, 1998, https://www.cato.org/publications/trade-briefing-paper/blessings-free-trade.

[4] Adam Smith, “That the Division of Labour is Limited by the Extent of the Market,” in An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, Book 1, Chapter III, http://www.econlib.org/library/Smith/smWN1.html#B.I.

[5] Donald J. Boudreaux, “Comparative Advantage,” in David R. Henderson, ed., The Concise Encyclopedia of Economics (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund Inc., 2002), www.econlib.org/library/Enc/ComparativeAdvantage.html.

[6] Council of Economic Advisers, “Chapter 4: The Benefits of Open Trade and Investment Policies,” Economic Report of the President (2009) (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, January 2009), https://georgewbush-whitehouse.archives.gov/cea/ERP_2009_Ch4.pdf.

[7] Cathleen D. Cimino-Isaacs, “U.S. Trade Policy Primer: Frequently Asked Questions,” Congressional Research Service, April 2, 2018.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Scott C. Bradford, Paul L. E. Grieco, and Gary Clyde Hufbauer, “The Payoff to America from Global Integration,” Peterson Institute for International Economics, Jan. 1, 2005, https://piie.com/sites/default/files/publications/chapters_preview/3802/2iie3802.pdf.

[10] Council of Economic Advisers, “Chapter 4: The Benefits of Open Trade and Investment Policies,” 132.

[11] Mack Ott, “International Capital Flows,” in David R. Henderson, ed., The Concise Encyclopedia of Economics (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund Inc., 2002), http://www.econlib.org/library/Enc/InternationalCapitalFlows.html.

[12] The illustration is based on Frederick Bastiat’s Selected Essays on Political Economy: “The Balance of Trade,” www.econlib.org/library/Bastiat/basEss.html?chapter_num=16#book-reader.

[13] Adam Smith, “Of Restraints upon the Importation from Foreign Countries of such Goods as can be Produced at Home,” in An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations.

[14] See Scott Lincicome, “Don’t Blame Free Trade. We Don’t Have it,” Foundation for Economic Education, Nov. 21, 2016, https://fee.org/articles/dont-blame-free-trade-we-dont-have-it/.

[15] Dean Russell, “Tariffs Kills Jobs,” Foundation for Economic Education, Feb. 1, 1962, https://fee.org/articles/tariffs-kills-jobs/.

[16] Chad P. Brown, “The Element of Surprise Is a Bad Strategy for a Trade War,” Peterson Institute for International Economics, April 16, 2018, https://piie.com/commentary/op-eds/element-surprise-bad-strategy-trade-war.

[17] Kyle Pomerleau and Erica York, “Modeling the Impact of President Trump’s Proposed Tariffs,” Tax Foundation, April 12, 2018, https://taxfoundation.org/modeling-impact-president-trumps-proposed-tariffs/.

[18] Alan S. Blinder, “Free Trade,” in David R. Henderson, ed., The Concise Encyclopedia of Economics (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund Inc., 2002), http://www.econlib.org/library/Enc/FreeTrade.html.

[19] Scott Lincicome, “Doomed to Repeat It,” The Cato Institute, August 22, 2017, https://object.cato.org/sites/cato.org/files/pubs/pdf/pa-819-updated.pdf.

[20] Gary Clyde Hufbauer and Kimberly Ann Elliott, “Measuring the Costs of Protection in The United States,” Peterson Institute for International Economics, January 1994, https://piie.com/bookstore/measuring-costs-protection-united-states.

[21] Erica York, “Lessons from the 2002 Bush Steel Tariffs,” Tax Foundation, March 12, 2018, https://taxfoundation.org/lessons-2002-bush-steel-tariffs/.

[22] Congressional Budget Office, “Has Trade Protection Revitalized Domestic Industries?” November 1986, xiii. https://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/cbofiles/ftpdocs/61xx/doc6186/doc25c-entire.pdf.

[23] United States International Trade Commission, “Harmonized Tariff Schedule (2018 HTSA Revision 5),” May 2018, https://hts.usitc.gov/current.

[24] United States International Trade Commission, “Interactive Tariff and Trade DataWeb,” April 2018, https://dataweb.usitc.gov/.

[25] Ibid.

[26] Ibid.

[27] United States International Trade Commission, “Harmonized Tariff Schedule (2018 HTSA Revision 5),” Chapter 61, 61-4.

[28] World Trade Organization, “Trade Policy Review, Report by the Secretariat, United States,” March 28, 2017, file:///C:/Users/rshuster/Downloads/S350R1.pdf.

[29] Erica York, “President Trump Approves Tariffs on Washing Machines and Solar Cells,” Tax Foundation, Jan. 30, 2018, https://taxfoundation.org/trump-tariffs-washing-machines-solar-cells/; and Erica York, “President Trump Announces Two Steep Tariffs on Steel and Aluminum,” Tax Foundation, March 2, 2018, https://taxfoundation.org/trump-steel-tariff-aluminum-tariff/.

[30] Donna Borak and Nathaniel Meyersohn, “White House slaps 25% tariff on $50 billion worth of Chinese goods,” CNNMoney, May 29, 2018, http://money.cnn.com/2018/05/29/news/economy/china-tariffs/index.html.

[31] Erica York, “Potential of Trade War Threatens New Tax Law’s Benefits,” Tax Foundation, April 6, 2018, https://taxfoundation.org/potential-trade-war-threatens-new-tax-laws-benefits/.

[32] Scott Lincicome, “Chinese Intellectual Property Policies Demand a Smart U.S. Trade Policy Response – One President Trump Doesn’t Appear to be Considering,” Cato Institute, Jan. 2, 2018, https://www.cato.org/blog/chinese-intellectual-property-policies-demand-smart-us-trade-policy-response-one-president.

[33] Scott Drenkard, “It’s Tariff Time: What Can Adam Smith Teach Us About Trade Policy Today?,” Tax Foundation, March 2, 2018, https://taxfoundation.org/adam-smith-trump-tariffs/.

[34] Kyle Pomerleau and Erica York, “Modeling the Impact of President Trump’s Proposed Tariffs,” Tax Foundation, April 12, 2018, https://taxfoundation.org/modeling-impact-president-trumps-proposed-tariffs/.

[35] Erica York, “Automobile Tariffs Would Offset Half the TCJA Gains for Low-income Households,” Tax Foundation, June 4, 2018, https://taxfoundation.org/automobile-tariffs-2018/.

Share this article