If you only read one article today about fringe benefits, make sure it’s “Revisiting the Taxation of Fringe Benefits,” by Jay Soled and Kathleen DeLaney Thomas. The authors shed light on an evolving area of taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. policy that policymakers would do well to pay attention to.

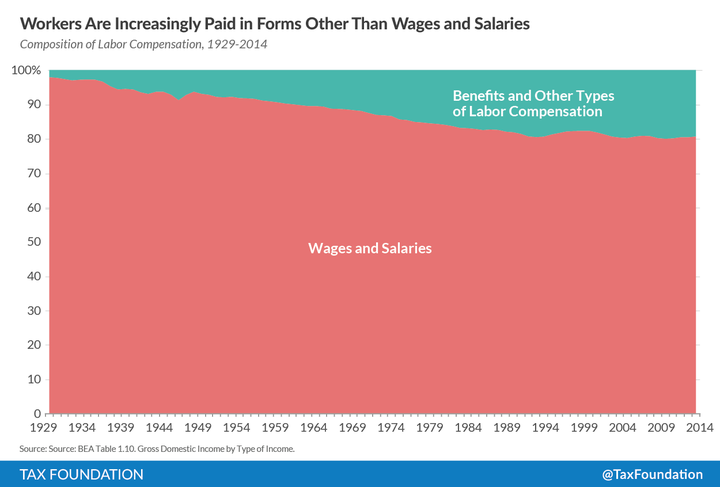

For some background: eighty years ago, it was relatively uncommon to offer workers compensation other than their regular wages and salaries. In 1929, only 1.9 percent of employee pay took the form of fringe benefits. By 2014, fringe benefits had risen to 19.2 percent of worker compensation.

For much of the 20th century, it was unclear which benefits were subject to federal taxes. The Internal Revenue Code of 1954 famously excluded employer-provided health insurance plans from taxation, but when it came to other benefits, it was often up to the IRS to determine whether they would be taxable or not. Finally, in 1984, Congress amended the tax code to formally clarify that fringe benefits were subject to taxation, with a few exceptions. Ever since, individuals have been required to report the value of fringe benefits received from their employers.

However, in recent years, more and more fringe benefits have gone unreported. As Soled and Thomas describe,

A surprising phenomenon has recently occurred. The country is awash in fringe benefits inuring to employees, a sizable portion of which currently goes unreported as taxable incomeTaxable income is the amount of income subject to tax, after deductions and exemptions. For both individuals and corporations, taxable income differs from—and is less than—gross income. . These newly minted fringe benefits generally fall into the scope of one of three categories: (1) “customer loyalty programs” such as frequent-flier miles, rental car usage, hotel frequency stays, and office supply purchases; (2) mixed-use (business/personal) assets such as cellular phones and home Internet service; and (3) workplace lifestyle enhancements such as the receipt of free lunches, massages, and dance classes.

The fringe benefits that Soled and Thomas describe make up an increasing portion of employee compensation. According to the federal tax code, individuals are suppoesed to report these benefits as taxable income. However, in practice, these benefits are often not reported, due to various practical difficulties with valuation and recordkeeping. How are taxpayers supposed to place a value on the frequent flyer miles they’ve accumulated? How are they expected to accurately estimate how often they use work-provided laptops for business purposes? And how can they keep track of all of the company-provided lunches they’ve received?

While valuing and keeping track of fringe benefits may be difficult, Soled and Thomas argue that doing so is vital, because the growing trend of unreported fringe benefits is “inequitable and inefficient.” This claim is spot on. For an illustration, imagine two employees, one of whom makes a salary of $100,000, and one of whom makes a salary of $80,000 and benefits worth $20,000, which largely go unreported. Although both workers receive the same overall compensation, the first employee is subject to a significantly higher tax burden than the second, which seems plainly unfair. Furthermore, this arrangement incentivizes companies to shift more compensation towards benefits, to help employees avoid taxes. This leads to an inefficient allocation of resources, towards services that employers might not have been willing to pay for in the absence of tax incentives.

After establishing the necessity of taxing fringe benefits and the difficulties of doing so, Soled and Thomas offer several concrete proposals for making sure that fringe benefits are reported properly:

- For benefits in the form of “customer loyalty points,” such as airline miles for personal travel, Soled and Thomas suggest that Congress set a fixed rate at which such points should be valued as income. For instance, lawmakers could decide that each airline mile provided by an employer should count as 1 cent of personal income. This would provide a simple way for taxpayers to determine how much these benefits are worth, making valuation much easier.

- For “mixed-use assets,” such as employer-provided cell phones, Soled and Thomas suggest that a fixed percentage of the cost of the asset be counted as a personal benefit for the employee. For instance, Congress could establish that, by default, an employer-provided cell phone is used for business 50 percent of the time and for personal use 50 percent of the time. Employees would then be required to report 50 percent of the cost of the cell phone as personal income. This would make it unnecessary for employees to calculate how often they used employer-provided assets for personal purposes, making recordkeeping much easier.

- For “workplace lifestyle enhancements,” such as free meals provided by the office, Soled and Thomas conclude that it is probably impossible for individual employees to keep track of all of the workplace perks their employees have paid for. However, these fringe benefits can still be taxed – by denying employers the ability to deduct these expenses from their tax returns. Essentially, Soled and Thomas propose shifting taxes on workplace lifestyle enhancements from the individual income returns of employees to the corporate or pass-through income returns of employers, making it more likely that these benefits would be reported.

Ultimately, Soled and Thomas conclude, a tax system in which fringe benefits are given a free pass is not sustainable. If many fringe benefits continue to go unreported, more and more employers will offer benefits instead of salaries, federal tax revenues will decline, and the IRS will lose credibility as a fair tax enforcer. Lawmakers should take this problem seriously and begin to craft policy solutions that move towards a neutral treatment of all compensation.

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

Subscribe