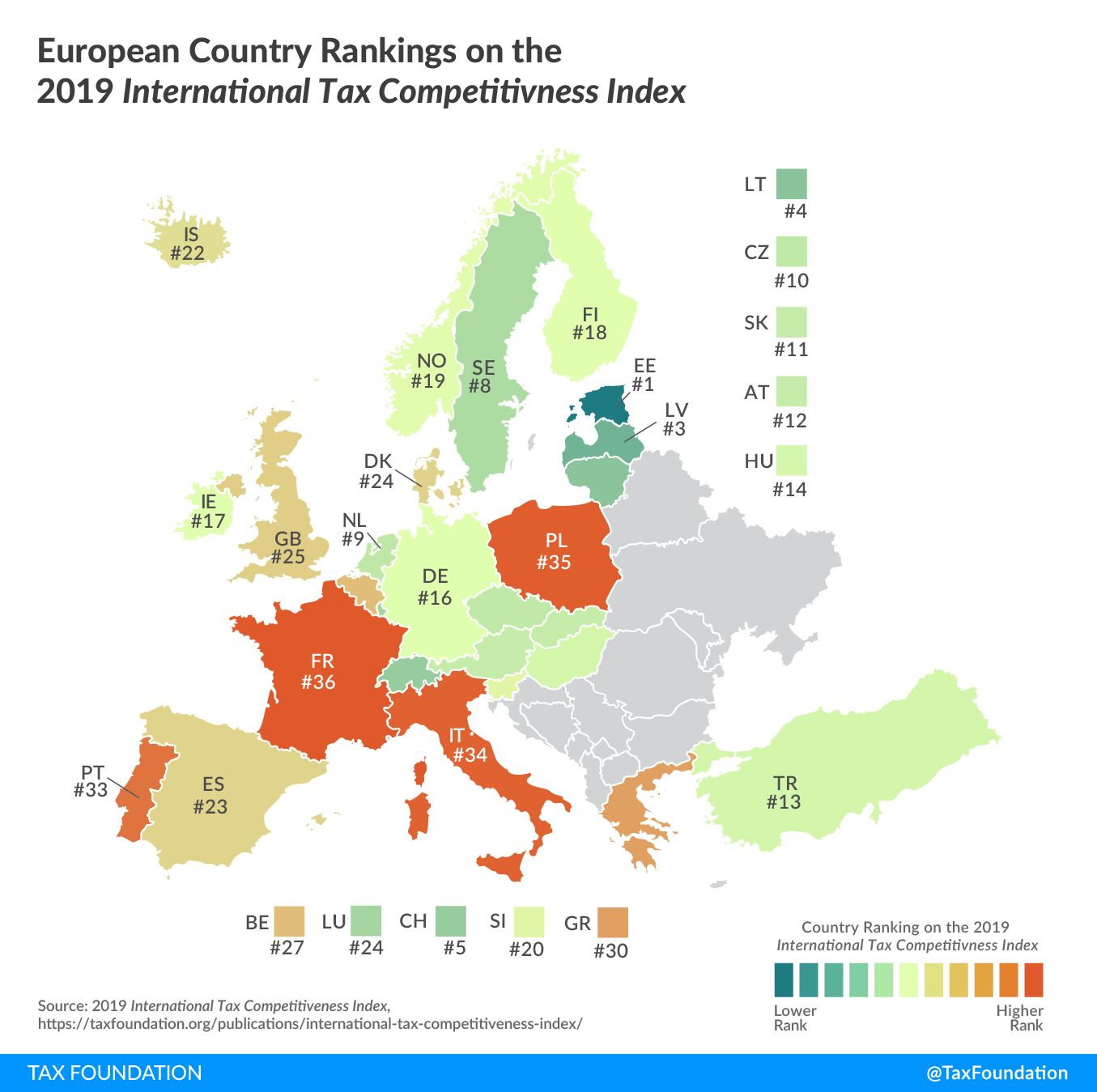

Spain’s Socialist party, led by Prime Minister Pedro Sanchez, and the left-wing Unidas Podemos have formed the first Spanish coalition government since 1930. The main measures agreed by Podemos leader Pablo Iglesias and Sanchez entail higher taxes for businesses and high-income earners, the partial rollback of the last labor market reform, and increases of the minimum wage and retirement pensions. The fiscal reforms that the coalition government is planning to implement will likely harm Spain’s fiscal competitiveness as measured by our International Tax Competitiveness Index (ITCI). In the past two years, Spain improved from 25th to 23rd to position itself behind Iceland and the United States. The reform program would reverse this shift and place Spain at 26th out of the 36 OECD countries.

Tax Hikes

According to the coalition agreement, income taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. will rise by 2 percentage points for those earning more than €130,000 a year, and by 4 percentage points for those who earn more than €300,000. This will push the statutory tax rate to reach 52 percent in regions like Catalonia, Asturias, or La Rioja. Furthermore, tax on capital gains above €140,000 would increase by 4 percentage points to reach 27 percent.

Large corporations will face a new minimum rate of 15 percent, while banks and energy firms will have to pay a minimum of 18 percent. The goal is to prevent companies from using tax deductions and loopholes to pay far less than the current official corporate tax rate of 25 percent. Nevertheless, this measure will make corporations in Spain lose competitiveness relative to their European and international counterparts, creating incentives to shift their activities elsewhere. This would hurt Spain’s ITCI ranking on international tax rules, causing it to fall from 19th to 25th on that measure.

Apart from these tax hikes, the coalition government is looking to introduce a tax that would target stock market transactions and a digital tax similar to the EU recommendations. This is a recurrent issue as a draft bill proposal to implement both policies was published by the Spanish Council of Ministers on October 19, 2019. The unilateral introduction of these taxes by Spain will impact taxpayers and hurt the economy. As for now, Spain is better off postponing the introduction of these taxes until and if an agreement on international digital taxation and transaction tax at the OECD or EU is reached.

Minimum Wage Changes and Regional Differences

Sanchez and Unidas Podemos agreed to raise the minimum wage from 45 to 60 percent of the average national wage by the end of the government’s four-year term.

In fact, for 2020, a 5.5 percent increase in the minimum wage has just been agreed upon, although by late 2018, Sanchez had approved an unprecedented 22 percent hike.

The rise in minimum wage, far from solving the inequality problem for which it was designed, might just exacerbate it. The statutory wage hikes might have an impact especially on the most vulnerable people in the economy: the unemployed and the low-skilled workers, by keeping them out of the labor market. With an unemployment rate of 14.2 percent, Spain has one of the worst unemployment data in the EU, only ahead of Greece[i].

The economic literature shows that minimum wage increases lead to a decline in the employment of unskilled workers (Jardim, Plotnick, et al., 2017[ii]; Neumark, 2014[iii]). Also, an IMF study[iv] from 2016 advises against implementing a statutory centralized minimum wage due to the specificities of regions and certain sectors. And Spain shows large and persistent differences in unemployment rates from one region to another. The lowest unemployment rate, 8.2 percent, is observed in Navarra, while in Extremadura, it reaches the high figure of 22.5 percent. These differences in unemployment rates are accompanied by differences in sector composition, regional productivity, fiscal competitiveness, and consequently, in total labor costs. These costs range from €2,085 in Extremadura to €3,102 in the Basque Country. Excessively abrupt centralized wage increases might lead to a decline in employment in regions with lower productivity and wages as Andalusia or Extremadura, which are already affected by high unemployment rates and lack of fiscal competitiveness. In 2019 both Andalusia and Extremadura were in the bottom half of the Spanish Regional Tax Competitiveness Index, ranking 13th and 15th respectively out of 19 regions.

Uncertainty Ahead

Last week, the IMF revised downwards its forecast for the Spanish economy, expecting GDP to rise 1.6 percent for 2020 and 2021, a cut of 0.2 percent. This comes after BBVA and the Bank of Spain also reviewed their predictions and warned about the economic implications of the policies to be implemented. Given the economic slowdown, all the fiscal measures planned could lead to an increase in the deficit and a lack of budgetary stability that Spain needs. On the other hand, the implementation of these reforms requires an ample political and social consensus that remains unlikely, given the fragmented and extremely polarized political landscape.

[i] The average unemployment rate in the EU is 6.3 percent, according to Eurostat (online data code: une_rt_m).

[ii] Ekaterina Jardim, Robert Plotnick, et al., “Minimum Wage Increases, Wages, and Low-Wage Employment: Evidence from Seattle,” NBER Working Papers No. 23532 (2017).

[iii] David Neumark, “Employment effects of minimum wages,” IZA World of Labor (2014).

[iv] “Cross-Country Report on Minimum Wages,” International Monetary Fund No. 16/151 (2016).

Share this article