Our analysis of the House Republican taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. plan was criticized by Jared Bernstein in The Washington Post last week. I have a couple of concerns with Dr. Bernstein’s thinking that I would like to share here.

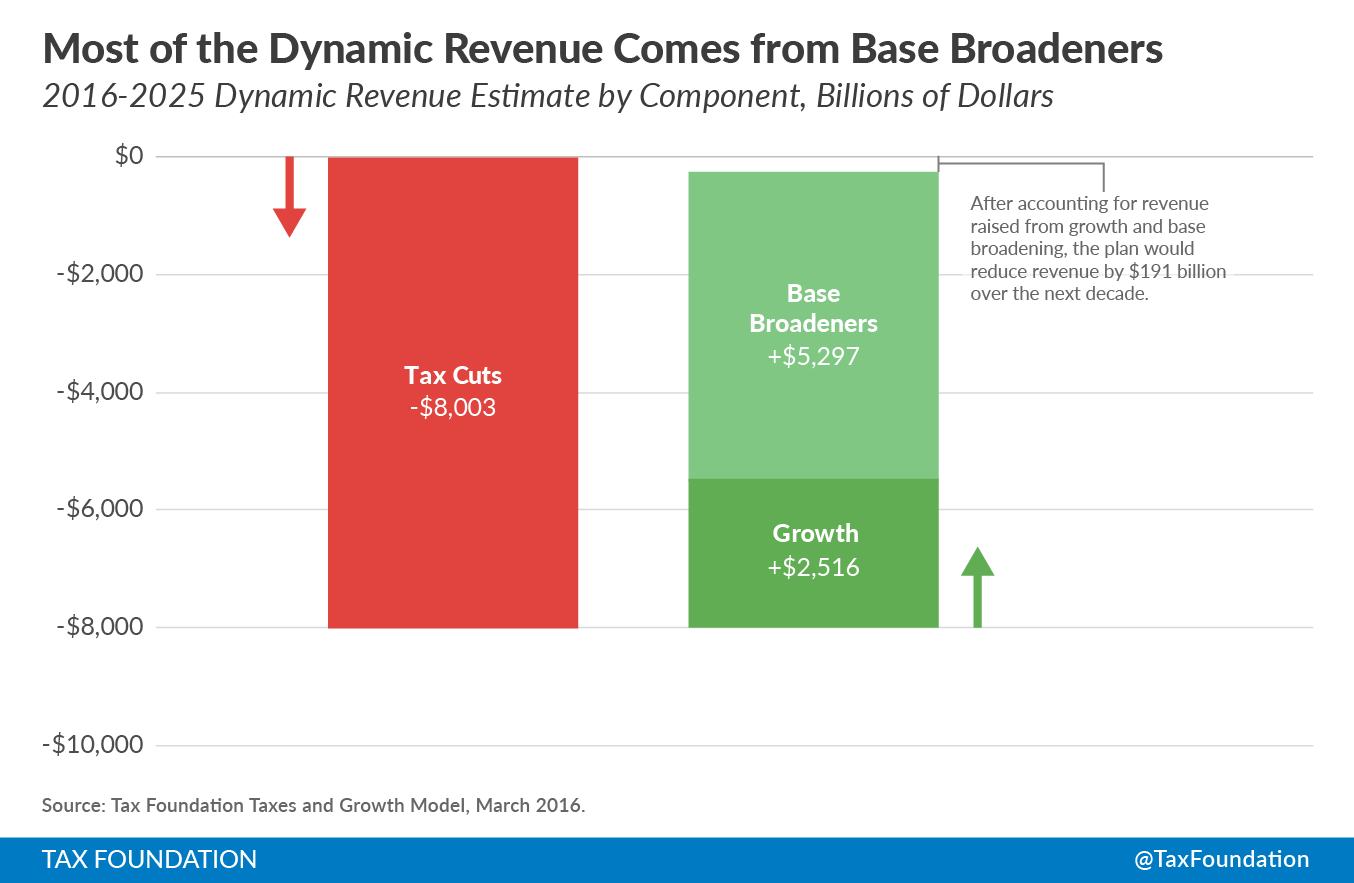

One issue with the thinking is a confusion of gross and net values. Bernstein asks, rhetorically, how a $2.4 trillion tax cut could pay for 92 percent of itself through economic growth. It’s a good question; a simple $2.4 trillion tax cut would not be able to. However, the House plan is not a $2.4 trillion tax cut; rather, it is a combination of about $8 trillion of tax cuts (which pay for about 31 percent of themselves) and more than $5 trillion of revenue from base-broadening provisions, which Bernstein does not mention at any point in his description of the plan. We illustrated the concept here:

The House plan, in other words, follows the conventional tax reform wisdom of broad bases and lower rates, and describing it simply as a tax cut elides important information. If I were a retailer and I chose to open eight stores in profitable locations and simultaneously close down six of my least profitable locations, it would be wrong to describe this as a mere change of two stores.

Another issue is with the consistency of Bernstein’s thinking generally. He asserts that tax cuts, “when they’re not paid for, generate larger budget deficits that crowd out private borrowing, raise interest rates and thus hurt investment.” This is a reversal from Bernstein’s previous position on the subject, where on his personal blog he argued the opposite: “the evidence for lower deficits leading to lower interest rates is surprisingly weak.” At Tax Foundation, we agree with Bernstein's blog post. We’ve explained why, and we can stick to that belief regardless of whose tax plan we’re analyzing. Can Dr. Bernstein?

Share this article