Cost recovery is the way the tax code permits firms to recover (or deduct) the cost of making investments. It plays an important role in defining a firm’s taxable income and can impact investment decisions. If the tax code does not have a way for firms to fully recover their investment costs, they may pay more tax than the tax liability associated with the income produced by their investments, increasing the cost of making those investments.

In the United States, business income taxes are calculated using four steps:

- Add up revenues (total income)

- Subtract expenses (deductions)

- Report the difference (taxable income)

- Multiply taxable income by tax rate to calculate total tax

Depreciation falls under Step 2. In general, companies are allowed to deduct most ordinary business costs, such as wages, salaries, maintenance, advertising, etc. However, certain categories of expenses are not allowed to be deducted immediately—companies cannot take an immediate deduction for the cost of their capital expenses. This category of expenses includes any business purchase that is expected to be useful for a long time: machinery, furniture, computers, buildings, etc.

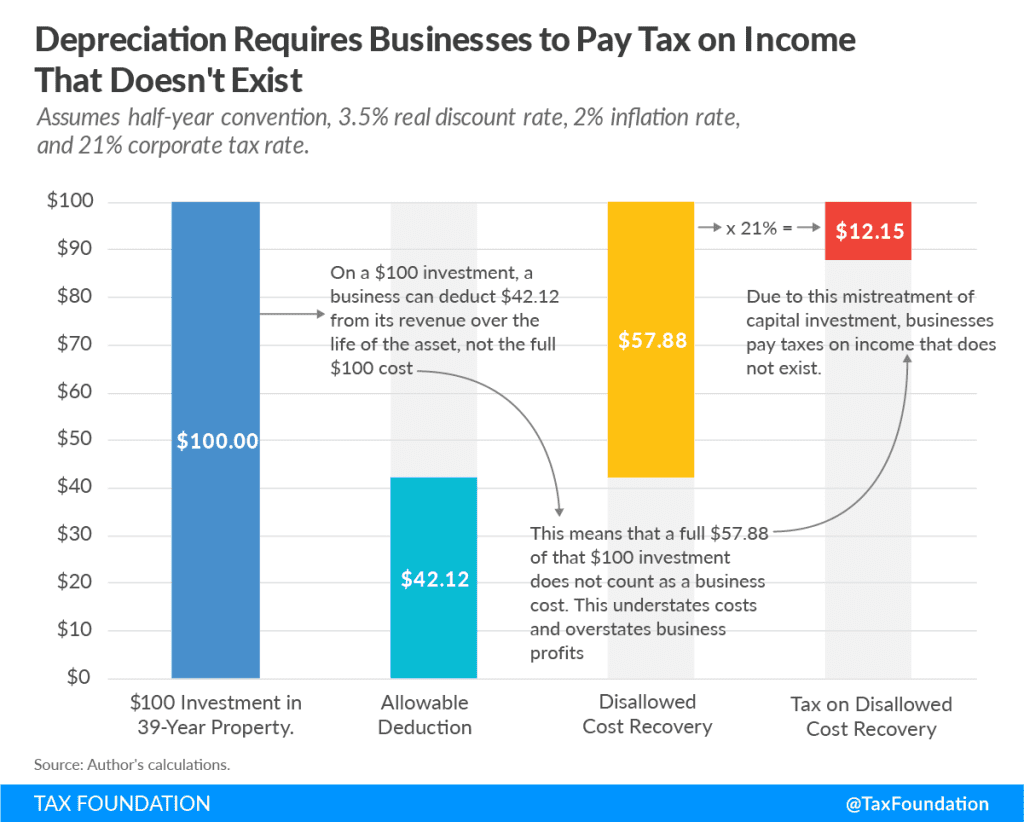

Instead of deducting the cost of capital expenses like regular business costs, the Modified Accelerated Cost Recovery System (MACRS) requires companies to take depreciation deductions over long periods of time. Delaying, rather than immediately subtracting, reduces the value of the deductions to the company below the original cost.

Under current law, companies must deduct investments in structures evenly over the life of the asset. For an investment in a commercial building, they spread their deductions over 39 years. For investment in a residential structure, they spread their deductions over 27.5 years.

Under current law, companies can deduct the full cost of their investment in machinery and equipment immediately, thanks to changes in the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017. However, this change is scheduled to phase out: in 2023, companies can immediately deduct only 80 percent of new investment in machinery and equipment, followed by 60 percent in 2024, 40 percent in 2025, and 20 percent in 2026, after which this provision will expire.

Under current law, companies can deduct the full value of their spending on research and development immediately. However, starting in 2022, companies will have to amortize their R&D spending over five years.

Ideally, the tax code would have full expensing for all investments. Investments should be deducted the year that they’re made, just as other business expenses are. Stopping short of full expensing and spreading out the value of deductions over several years raises the cost of investment, as a dollar in the future is worth less than a dollar now, thanks to the time value of money and inflation. This increase in cost slows economic growth, productivity growth, and wages.

| Gross Domestic Product | 5.1% |

| Capital Stock | 13.0% |

| Wage Rate | 4.3% |

| Full-Time Equivalent Jobs | 1.02 million |

| Source: Tax Foundation General Equilibrium Model, November 2019 | |

A neutral cost recovery system (NCRS) adjusts the deductions a company would normally be allowed to take for an investment in a building or structure in order to maintain their value in real terms. These adjustments prevent depreciation deductions from eroding in value over time due to inflation and the time value of money. Economically, these adjustments provide the same treatment as full expensing, or as if the business could take the full deduction for their investment immediately in the year it was made.

Without an adjustment, delaying depreciation deductions is akin to a company providing an interest-free loan to the government. The goal of neutral cost recovery is to approximate the treatment a company would receive under full expensing, which can only be accomplished if, like the interest charged on a loan, the adjustment accounts for both inflation and the time value of money. That is because depreciation deductions are less valuable to companies over time due to both factors.

This portion of the NCRS adjustment would be fixed at the historical, real marginal after-tax rate of return that physical capital has earned for decades—approximately 3 percent. This rate recognizes the time value of money that companies forgo when they are prevented from immediately deducting their outlays on capital investments, and in combination with an inflation adjustment, allows them to fully recover their capital investment outlays in real terms.

It is ideal to allow the inflation portion of the NCRS adjustment to vary each year, as this means all taxpayers get the same adjustments year to year as inflation rises or falls. If the inflation rate were locked in place when an investment was made, then dramatic movements up or down in the inflation rate—as occurred from the late ’60s through the early ’90s—would distort the real value of the write-offs and lead to radically different treatment of investments made at different times. A variable inflation measure allows the adjustment to track changes in inflation and ensures all taxpayers get the same adjustments year-to-year that reflect actual conditions.

Implementation of a NCRS would be easy with any tax software package and would not require additional work from the firm. Firms commonly use a software package that calculates an asset’s remaining basis after taking yearly write-offs and holds the basis over to become the adjusted basis for the next year. Under a NCRS, this remaining basis would be bumped up by the adjustment factor of inflation plus 3 percent. These year-to-year basis adjustments would be given out by the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) each year, and the firm’s software package would read the adjustment along with all the other tax tables and parameters of the tax system.

Using the Tax Foundation General Equilibrium Model, we estimate that full expensing would reduce federal revenue by about $1.6 trillion on a conventional basis between 2021 and 2030, and by $809 billion dynamically when considering the increase in tax revenue stemming from a larger economy.

A big part of the cost of full expensing is transitory, as investments that were made before enacting full expensing are still being written off in addition to new investments. This combination raises the total cost of expensing in the first 10 years of the policy. As legacy write-offs are completed, the cost of full expensing falls over time.

| 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | 2025 | 2026 | 2027 | 2028 | 2029 | 2030 | 2021-2030 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional (billions) | -$62 | -$130 | -$149 | -$170 | -$191 | -$204 | -$212 | -$191 | -$172 | -$156 | -$1,637 |

| Dynamic (billions) | -$44 | -$102 | -$109 | -$117 | -$124 | -$117 | -$102 | -$60 | -$18 | -$16 | -$809 |

| Source: Tax Foundation General Equilibrium Model, November 2019 | |||||||||||

A NCRS can help reduce the budgetary cost while preserving the full present-value of write-offs firms would receive under full expensing. We estimate that providing neutral cost recovery for structures and full expensing for all other assets would reduce federal revenue by $1.26 trillion between 2021 and 2030, and reduce federal revenue by $386 billion on a dynamic basis.

| 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | 2025 | 2026 | 2027 | 2028 | 2029 | 2030 | 2021-2030 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional Revenue (billions) | -$21 | -$94 | -$111 | -$131 | -$152 | -$165 | -$176 | -$153 | -$133 | -$126 | -$1,261 |

| Dynamic Revenue (billions) | -$3 | -$65 | -$70 | -$77 | -$83 | -$77 | -$63 | -$18 | $25 | $46 | -$386 |

| Source: Tax Foundation General Equilibrium Model, November 2019 | |||||||||||

The cost of an NCRS starts low, but rises over time. This is because firms take larger deductions in later years, which means that the cost in years outside the budget window are higher. We estimate that the long-run annual cost of neutral cost recovery for structures and full expensing for all other assets is $61 billion on a conventional basis (in 2020 dollars).

Full expensing and neutral cost recovery for structures would increase the capital stock and investment across all 50 states, increasing full-time equivalent jobs in state economies. In total, we estimate that the combined effect of both policies would increase the capital stock by 13 percent, or $4.8 trillion, and increase the number of full-time equivalent jobs by 1.02 million in the long run.

Full expensing and neutral cost recovery would increase wages by 4.3 percent in the long run, and long-run gross domestic product (GDP) would increase by 5.1 percent, according to the Tax Foundation General Equilibrium Model.

To illustrate the potential impact that these policy changes could have on job and capital stock growth in each state, explore our interactive map below.

In the long run, improved cost recovery matters for wages because expensing increases investment, which is key to productivity growth. Contrary to some skepticism, the link between productivity and wages remains strong: as a recent paper from Harvard economists Anna Stansbury and Lawrence Summers found, from 1973-2016, a 1 percent increase in productivity has been associated with a .7 to 1 percent increase in median and average compensation.

Existing studies of accelerated depreciation have shown that it helps increase wage growth. A recent paper from economist Eric Ohrn in the Journal of Public Economics examined how manufacturing fared in different states based on whether they adopted accelerated depreciation policies approved at the federal level. The paper found that states that implemented accelerated depreciation in their tax codes led to a 2.5 percent increase in compensation per employee in manufacturing, relative to states that did not.

Reforms like neutral cost recovery are especially helpful for manufacturing and other capital-intensive industries. Not allowing full deductions for capital investment means the tax code favors capital-light companies and disfavors manufacturers.