The Cadillac TaxThe Cadillac Tax is a 40 percent tax on employer-sponsored health care coverage that exceeds a certain value. The aim: to curb health-care cost growth, reduce favorable tax treatment of employer-provided insurance, and help fund the Affordable Care Act (ACA). It was repealed in late 2019 before taking effect. , an excise taxAn excise tax is a tax imposed on a specific good or activity. Excise taxes are commonly levied on cigarettes, alcoholic beverages, soda, gasoline, insurance premiums, amusement activities, and betting, and typically make up a relatively small and volatile portion of state and local and, to a lesser extent, federal tax collections. on high-cost health insurance plans provided by insurers, has been under fire for quite some time. Recently, presidential candidate Hillary Clinton added her voice to the mix.

“Too many Americans are struggling to meet the cost of rising deductibles and drug prices,” Mrs. Clinton said in a statement. “That’s why, among other steps, I encourage Congress to repeal the so-called Cadillac taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. .”

This is significant for several reasons: the first of these is that the tax is actually a fairly substantial one, potentially about $91 billion over the next decade. Furthermore, the tax is part of the Affordable Care Act, the signature legislation of President Obama’s first term. Rolling back aspects of the Affordable Care Act is usually a political priority more associated with Republicans.

It’s also notable because Clinton has linked the Cadillac Tax to a trend of rising deductibles, implying that the plan is working as designed. (While this connection is widely covered by many news outlets, it still seems to have eluded certain journalists.)

While rising deductibles are unpopular, many economists actually think they’re a good idea. And in fact, today a group of 101 prominent tax and health economists wrote a letter to key members of Congress "urging" them not to eliminate the Cadillac Tax without replacing it with some kind of substitute. The group is impressive in its scope; it contains economists from a wide variety of think tanks and universities, including several people who had a role in designing the law in the first place.

Why do economists differ from the general public on this issue? Well, they, like the public, dislike rising health care costs. However, they see that problem as a problem caused by bad tax policy. The letter makes this very clear:

For decades economists and health policy experts of all political persuasions have agreed that the unlimited exclusion of employer-financed health insurance from income and payroll taxes is economically inefficient and regressive. The Affordable Care Act established an excise tax on high-cost health plans (the so-called ‘Cadillac tax’) to address these issues.

The Cadillac tax will help curtail the growth of private health insurance premiums by encouraging employers to limit the costs of plans to the tax-free amount. The excise tax will discourage the provision of insurance that covers such a large proportion of health care spending that consumers have little incentive to insist on cost-effective care and providers have little incentive to provide it. As employers redesign health insurance plans to hold costs within the tax-free amount, cash wages or other fringe benefits will increase.

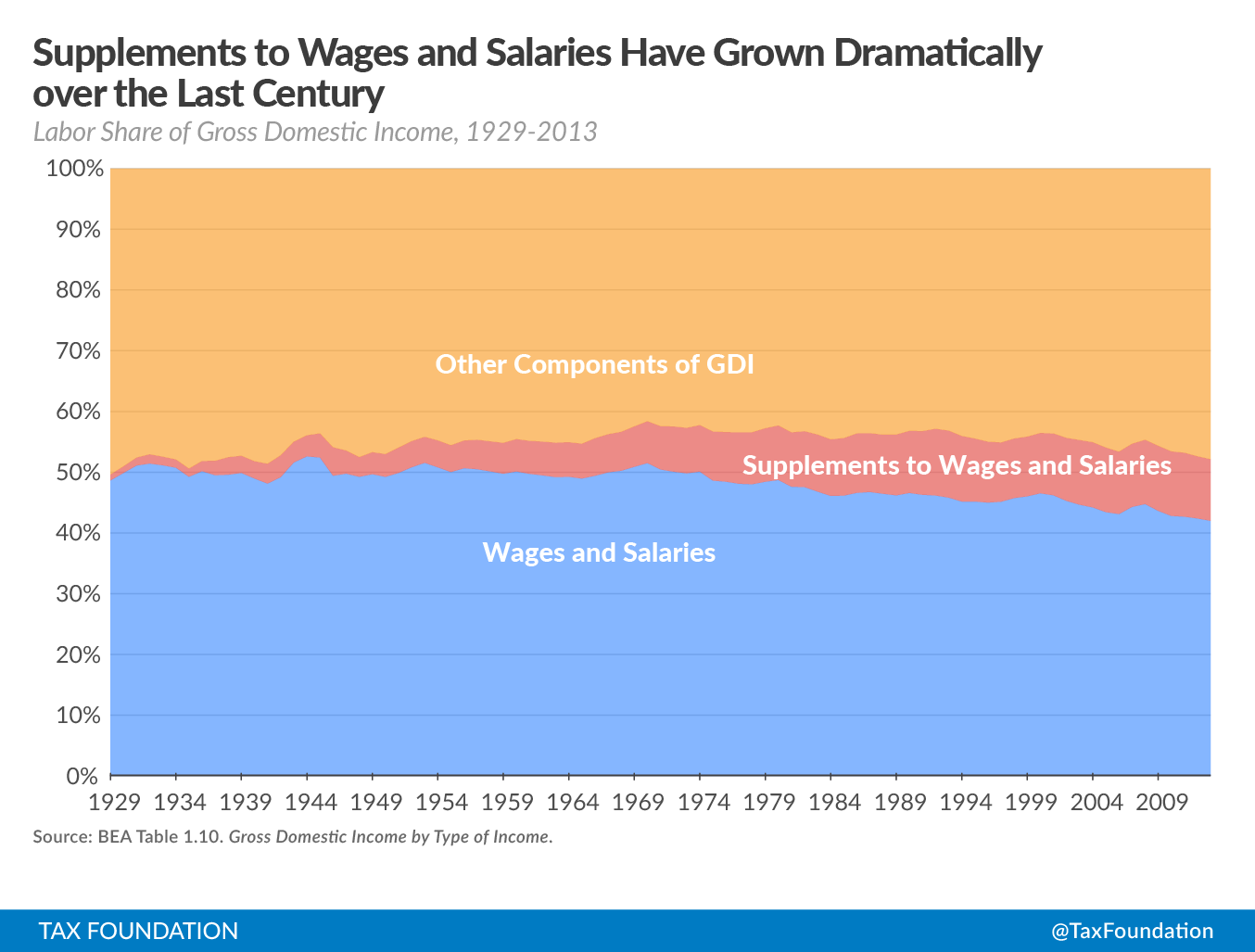

This argument has a lot of parts to it, but all of them are sound. Wages are taxed, while employer-provided health premiums are not. As a result, employers forego some of your wages and send them over to your health plan instead. This is actually a very visible trend in the long-term data for the U.S.; as measured by the BEA, fringe benefits have grown dramatically as a share of national income, crowding out wages and salaries. The BEA refers to employee benefits as a whole as "Supplements to Wages and Salaries."

Because of these generous health plans (and commensurately un-generous wages), we end up spending too much on our health plans and not enough on other things. In part, this is because if you have a deductible, you actually start paying attention to which health providers are offering services in a cost-effective way.

The language used by Hillary Clinton in favor of repeal, compared with the language used by the economists, reveals a sharp contrast: the economists believe the tax curbs rising health care costs, while Clinton’s language implies that the tax contributes to them.

The economists’ argument is stronger; it considers a broader, better measure of health care costs—one that includes the costs paid by the employee, but also includes the costs paid by the employer on the employee’s behalf; it recognizes how the proliferation of high-premium health insurance plans has limited our ability, as a country, to spend money on much-needed other things.

Share this article