Fiscal Forum: Future of the EU Tax Mix with Dr. Christoph Spengel

15 min readBy:In July 2024, I had the opportunity to interview Professor of International Taxation at the University of Mannheim Business School, Dr. Christoph Spengel, about the future of the EU taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. mix. A lightly edited transcript from that interview is below and shows the importance of balancing different types of revenue-raising policies with societal goals.

Sean Bray: How do you perceive the current EU tax mix as it stands today?

Christoph Spengel: I consider the EU tax mix as direct and indirect taxes. One standalone point in the EU is that we have had a harmonized value-added tax (VAT) system since the beginning of the European Economic Union in the 1960s. And all Member States that joined the EU later had to adopt this. The most important direct taxA direct tax is levied on individuals and organizations and is not expected to be passed on to another payer (unlike indirect taxes such as sales and excise taxes), though economic incidence can still fall upon others. Often with a direct tax, such as the individual income tax, tax rates increase as the taxpayer’s ability to pay, or financial resources, increases, resulting in what is called a progressive tax. Article 1, Section 9, of the US Constitution requires direct taxes to be apportioned by state population, though the 16th Amendment establishes that income taxes are not subject to this requirement. is the personal income tax (PIT). So, the corporate income taxA corporate income tax (CIT) is levied by federal and state governments on business profits. Many companies are not subject to the CIT because they are taxed as pass-through businesses, with income reportable under the individual income tax. (CIT) is not that relevant. I think, above all, it is an advantage to have that mix of income taxation and consumption taxation because both the PIT and VAT are the most important taxes in generating tax revenue. In Germany, both contribute to 75 percent of total taxes. And, within the last 25 years, we’ve faced different crises. It started in 2000 with the dot-com crisis. In an economic crisis, employment does not increase, but since there are savings, consumption is an automatic stabilizer of the decrease in the personal income tax. During the financial crisis in 2006 and 2007, the income tax went down, but the consumption taxA consumption tax is typically levied on the purchase of goods or services and is paid directly or indirectly by the consumer in the form of retail sales taxes, excise taxes, tariffs, value-added taxes (VAT), or income taxes where all savings are tax-deductible. was a stabilizer. And it was a bit different in the pandemic because most Member States had a special COVID-19 tax law to stabilize. But still, I find this is a real advantage, and this should hold for all the new Member States.

Sean Bray: How should the EU reform its tax mix in the medium term?

Christoph Spengel: It’s a good question. The answer is hard to find, since unlike the United States, the EU is not a political union, and the European Parliament only has some power but has no budget. So that means above all, taxation belongs to the Member States. Measures of harmonization should be clearly pointed out. We have VAT and PIT outside the scope of the European Commission. That follows the principle of subsidiarity in the Treaty of the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU). And that’s a bit binding.

In the last decades, there have been a lot of efforts and proposals to harmonize the corporate income tax. It started with the common corporate consolidated tax baseThe tax base is the total amount of income, property, assets, consumption, transactions, or other economic activity subject to taxation by a tax authority. A narrow tax base is non-neutral and inefficient. A broad tax base reduces tax administration costs and allows more revenue to be raised at lower rates. , the CCCTB, which would have introduced a harmonized tax base for the corporate income tax and a mechanism to allocate the consolidated income to the Member States where the multinational corporations are active. And that was without thinking of corporate tax rates. I was in favor of harmonizing the tax base because if you harmonize or put a proposal on the table, then you should weigh the pros and cons.

The pro is simplification for both the taxpayers and the companies, because within Europe, they have a single set of accounting standards and that reduces compliance costs for monetary things. It would also be simpler for tax administration. The con is that you hand back the right to set the tax base with tax incentives.

But actually, that’s not true because what was on the table was a set of tax accounting standards which were a good compromise of existing national standards. And of course, if you want to promote investment, you have alternatives like tax credits or something like that, which come after the computation of the tax base. Allocation of a consolidated tax base was complex and difficult. And, because it was not at all clear, what does that mean for the tax revenues of the countries involved?

And now I step 20 years to present the two-pillar project. Pillar One, which is still on the table, wants to allocate part of multinational income to come to market jurisdiction. So, it’s again allocating taxing rights to market jurisdictions. And that’s similar to allocating a consolidated tax base via a formula. And interestingly, we talk about Europe. We have a global minimum tax in the EU, effective beginning in 2024. This is a minimum tax rate, but we forgot to harmonize the tax base, and you cannot have a harmonization with the EU. Taxes are very simple. The tax burden is the product of the tax base multiplied by the tax rate. And if you want to harmonize, you have to consider those things. Because now we have two worlds. We have the global minimum tax within Europe, and we still have our domestic, anti-avoidance measures where we have to compute tax burdens according to a non-harmonized set of tax accounting rules.

And now, if you’re a bit aware, you say, “where should we go?” I think that introducing a binding global minimum tax in the EU is a clear disadvantage for location decisions within the EU because the minimum tax is 15 percent, but it’s very complicated. This minimum tax can be collected by a jurisdiction which has a standard tax below 15 percent. So, there would be a domestic top-up tax. Or if there is no domestic top-up tax, the resident country of the headquarters might tax the difference up to 15 percent. And, to give you an example, this is a clear disadvantage for EU-based multinationals because EU-based multinationals have to pay worldwide in each jurisdiction at least 15 percent, and I don’t think that the US will introduce such a thing. My country, Germany, is an interesting country for the automotive industry. Porsche is there, Audi is there, and the headline tax rate of Hungary is 9 percent. A German multinational investing in Hungary has to pay at least 15 percent, right? And Hungary can collect the top-up tax. Because why should Germany take that? Now, consider a US competitor of Audi sets up a production plant in Hungary. They have to pay 9 percent. And that’s an EU directive that can only be changed unanimously. And others, if they have comparative advantages, why should they pay 9 percent? If the US or China doesn’t enter in the global minimum tax, I think that we are on the wrong way.

In the EU in the last 10 years, we have introduced only anti-tax avoidance measures, which is the Anti-Tax Avoidance Directive (ATAD) with a harmonized CFC rule on interest deduction limitation. We have public country-by-country reporting. We disclose secrets which we were not obliged to disclose before even not in consolidated accounts. And now we have a global minimum tax again. The EU is a bit ring-fencing it, and that’s not good.

Sean Bray: What role should capital taxation play in the tax mix?

Christoph Spengel: I see some interrelated things when you ask for a stable fiscal position and capital taxation. The personal income tax and value-added tax are the most important taxes and it’s good to have that tax mix. We also see that part of the income of very rich individuals is not taxed or is taxed only very low. And have you heard about the proposal of Mr. Zucman and others to tax billionaires? It’s on the table. I always ask, why only billionaires? Why not people having €900 million? So, a problem of capital taxation is that the corporate income tax is a backstop for the personal income tax because the very rich have their investments in business. And they have their holdings and so on.

Why do they only pay little taxes on their economic income? Because you cannot go through a corporation, and now Mr. Zucman says to have a net property taxA property tax is primarily levied on immovable property like land and buildings, as well as on tangible personal property that is movable, like vehicles and equipment. Property taxes are the single largest source of state and local revenue in the U.S. and help fund schools, roads, police, and other services. . But I would like to talk about the inheritance and gift taxA gift tax is a tax on the transfer of property by a living individual, without payment or a valuable exchange in return. The donor, not the recipient of the gift, is typically liable for the tax. . Because how should I collect a property tax? I have almost no information, actually. And that’s not the role of the European Commission. The inheritance and gift tax is in the Member States. But, if you die, that’s the last point in time where you transfer income to the next generation or your last consumption. And here we should think of having a stable inheritance and gift tax and think about not leaving business assets almost untaxed. That relates to capital taxation. If you increase income taxes, that does not increase the tax burden of corporations. Now, if the profits are in a corporation leave them there. It’s not to increase the corporate tax rates because they’re relevant for investment and location decisions, but to have fairer and sustainable capital taxation in the hands of the owners. And the last point in time is the inheritance.

Sean Bray: How should the EU reform the VAT?

Christoph Spengel: The VAT is very vulnerable. The tax system has a mistake in the design. The studies promoted by the European Commission about the EU show a tax gapThe tax gap is the difference between taxes legally owed and taxes collected. The gross tax gap in the U.S. accounts for at least 1 billion in lost revenue each year, according to the latest estimate by the IRS (2011 to 2013), suggesting a voluntary taxpayer compliance rate of 83.6 percent. The net tax gap is calculated by subtracting late tax collections from the gross tax gap: from 2011 to 2013, the average net gap was around 1 billion. , and the estimates are huge. It’s more than €100 billion in lost tax revenue per year. That’s a lot, and the system is vulnerable to tax fraud because the incidence is on the consumer, but we collect it on each chain in the value creation process. If you have a business-to-business transaction that you charge VAT, then the buyer of the goods and services may deduct that as input VAT. So, there is a collection of tax, but not an incident of the tax. However, this system is vulnerable because you may deduct input if you show an invoice, but if you don’t match that or trigger that, the VAT has actually been transferred to the tax authorities, and that must be released. Against tax fraud, you can write what you want in a tax law, but you have to make the system waterproof. It’s only a little change in the system and everything is on the table. The buzzword is reverse charge.

Then with regard to digital business models, if you take electronic marketplaces or you take sports gambling, there’s a lot of tax evasion, and here we have to invest. If you offer an apartment on Airbnb, you’re a direct competitor to a hotel. And why should one pay no VAT? And the market is increasing. We talk about a stable fiscal position, and the VAT has many legal loopholes and is also very vulnerable. And that’s something where the commission and the Member States should put in effort. It’s very important.

Sean Bray: Should the EU focus only on PIT and VAT or are there other taxes to consider reforming?

Christoph Spengel: I would say there are others. As I say, VAT and PIT are the most important taxes regarding the contribution to the tax revenue. I also considered the corporate income tax as relevant, but the next step here should be to reduce compliance costs, and therefore, have more simplification. I talk about the tax base and also allocating profits to Member States or jurisdictions where they are active regarding environmental taxes. We would have carbon certificates EU-wide. That would be nice. Climate change is a global issue. If we reduce carbon emissions by 10 percent, everybody benefits around the world. It’s very controversial in particular in the public. So, if I were in charge, I would like to have the United States, China, and India around the table and say, we live on one planet, right? I think of the generation of my daughter and so on. And, we see climate change, but we should put effort on the global side and take the most relevant countries and say, “okay, we pay” then for Africa and for parts of South America because there are some global costs.

Sean Bray: How should we think about the differences in burden between capital and labor taxation?

Christoph Spengel: I think the most important is personal income tax but that can be difficult, so we talk about labor taxation and capital taxation because labor is income from employment. And I would say agriculture is capital, business is capital, self-employed is labor and capital, rental income is capital and a type of income, which is called capital income, dividends, interest, and capital gains. So, it’s capital, and it’s labeled. I think a uniform or more unified taxation of capital income would simplify the tax system and would avoid arbitrage between different categories of capital income.

To give you an idea, if you rent a house or apartment in Germany, you receive rental income. But the capital gain upon the disposal of real estate is not taxed if it’s long-term. So, if you still dispose more than 10 years after acquisition, it’s not taxable. Whereas if you dispose shares there, the capital gain is taxed. And, again, that would increase the fairness and simplification because why fairness? Because richer households can afford investment in real estate. So, I would like to have that be more uniform and, with the labor taxation, we have other taxes on labor which are sometimes direct. If you talk to Austria, they have payroll taxes. France has payroll taxes. We rather have some difficulties in the capital income, and that’s why I say it’s important to have an equal treatment and also an indirect relation between capital income and labor income. Capital income is also corporate profits. And now I come a bit from economics.

Who bears the corporate income tax? So where is the incidence? You can say, the tax reduces profits as a cost and the incidence is at the shareholder level. However, if you take the tax as a cost, you could say, I transfer the costs in my prices to the consumer market, or I substitute costs. And what we see from some recent studies in Germany, we have also a local trade tax where we have good data. If the corporate tax increases, we have a lower increase in salaries. So that means part of the corporate tax is also on labor. And that’s interesting in a way. I would leave it as it is, simple.

In addition, and that’s also up to the Member States, we are an aging population in Europe. That means for the young, we should increase the ability to accumulate capital for retirement. We should have private savings which would be defined quite broadly as a move to a consumption tax that you can deduct savings from your taxable incomeTaxable income is the amount of income subject to tax, after deductions and exemptions. Taxable income differs from—and is less than—gross income. . That is something which would enable individuals to accumulate more capital for retirement. That’s what I tell my students, that they should plead for more elements of the consumption tax because you can accumulate maybe 15 percent more capital depending on the interest rate.

Sean Bray: What do you think the EU should do going forward with Pillar Two?

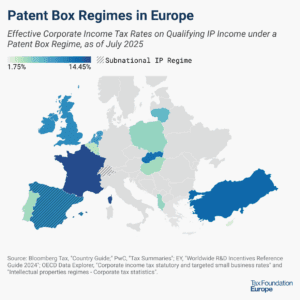

Christoph Spengel: I would abolish the minimum tax. In the middle of the 1990s, 30 years ago, we had a global forum on unfair tax competition. It’s not the multinationals that are tax avoiders. There are jurisdictions that also offer subsidies which can be unfair. And we talked about Belgium coordination centers and Dutch financing company regimes. There was a political decision that we remove the unfair elements in the tax system and not introduce new ones. That lasted 15 years, but then we started with IP patent boxes. So, the same thing, but then politically accusing the tax avoidance, the multinationals, and that’s unfair.

Now you mentioned subsidies. A global minimum tax is not the end of tax competition. There is what we now observe more tax competition in the personal income tax for expatriates and so on. And you can use cash. Look at what Germany is doing by offering €4 billion to Intel to build a factory or €500 million in Saarland to have a chip factory from the US. Tax competition as a whole does not stop, and I would abolish the global minimum tax because in Europe, it’s a clear disadvantage as we have figured out. I would say to the governments that we need a level playing field, but this is hard. I particularly think it is very hard with regard to China. I think most relevant is China. I think the United States has the best evidence-based tax policy, but it’s not Trump who started saying America first. It’s been the American tax policy for five decades, and what I’m telling you is that tax policy is about domestic efficiency. No one talks about global efficiency. What is good for the world? And that’s something, it’s not Europe. It’s global. It’s the same with environmental taxes, that it’s about a global stable tax revenue that is fair. Also, with regard to developing countries, we could talk about a lot of tax topics. I think it’s necessary to broaden the view on the global context.

Sean Bray: What does “tax fairness” mean to you?

Christoph Spengel: Tax fairness is the principle of equity. You can do that on an individual level. Personal tax should be fair, and the tax system should be based on a net principle and a progressive taxA progressive tax is one where the average tax burden increases with income. High-income families pay a disproportionate share of the tax burden, while low- and middle-income taxpayers shoulder a relatively small tax burden. rate. That’s one thing of fairness. Then, the famous couple, Peggy and Richard Musgrave, had international equity, and that’s the fairness between countries. That means that countries should take a fair share of profits which can be attributed to them. That should be something you could try together with the global players to have that fairness between jurisdictions because business models are changing due to digitalization and mobilization. That means that value creation is not necessarily linked to your market. You have one question about the digital economy, and I wouldn’t tax the digital economy differently from traditional business models. We have to understand the digital economy and you could talk about things.

On the corporate income tax, I take the position of Mr. Reuven Avi-Yonah, who said, if I can use transfer pricing in the traditional way, I will do that. But the remainder is a combination. If you create a patent or machine learning, something new appears, and that’s a combination of labor and capital profit. Amount A in Pillar One has the same idea. So, that is one question whether to go in this direction or traditional profits.

In addition, I refer to the tax mix. Say there is income tax and consumption tax. And the income tax belongs to where value is created, and the consumption tax is destination-based. And of course, in market countries where Google has no representations, there are consumers. Therefore, to have stable and sustainable tax revenue, you shouldn’t forget the VAT on electronic services that goes to the destination country.

Sean Bray: Is there anything we missed that you’d like to cover?

Christoph Spengel: I have dealt, not actively, but as a commentator, with tax fraud like Cum-Ex, short sales, and other dividend arbitrage systems, which is criminal at least in Germany. There have been some court decisions and then I see, I also talked about VAT fraud, but regarding financial income, I see that as an international scene. I think within Europe, we should put more effort into closer cooperation with the tax authorities. We already have some directives on administrative cooperation, but I’m talking about tax fraud. We have Europol, but they only deal with indirect taxes. And that should also be based on direct taxes because we lose a lot of money. It’s about €25 billion and that’s especially important right now in Germany because we have difficulties setting up a federal household next year that is compliant with our constitution.