One of the reoccurring themes we will hear from lawmakers as they craft a taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. reform plan is the importance of reducing the tax burden on hard-working American families. As well-intentioned as this goal is, it will be very difficult to achieve because past efforts to help middle-class taxpayers have made the U.S. federal tax system extremely progressive—high-income families pay a disproportionate share of the tax burden, while the poor and middle class shoulder a relatively small tax burden.

If history is any guide, the extreme progressivity of the U.S. tax system will influence the policy options that lawmakers choose in designing their tax reform plan and it will shape the political rhetoric over the direction of tax reform.

For example, both the House GOP tax reform “Blueprint” and President Trump’s tax reform outline propose reducing the number of individual tax bracketA tax bracket is the range of incomes taxed at given rates, which typically differ depending on filing status. In a progressive individual or corporate income tax system, rates rise as income increases. There are seven federal individual income tax brackets; the federal corporate income tax system is flat. s from seven to three, while reducing tax rates. However, because high-income taxpayers bear such a disproportionate share of the tax burden, any attempt to simplify the income tax code and lower tax rates will inevitably be met with political charges that the tax plan favors “tax cuts for the rich.”

In order to avoid the appearance of helping the rich, we are likely to see tax writers expand or increase various tax creditA tax credit is a provision that reduces a taxpayer’s final tax bill, dollar-for-dollar. A tax credit differs from deductions and exemptions, which reduce taxable income, rather than the taxpayer’s tax bill directly. s in order to make their distributional tables seem more balanced. Expanding or creating new tax credits runs contrary to the goal of making the tax code simpler.

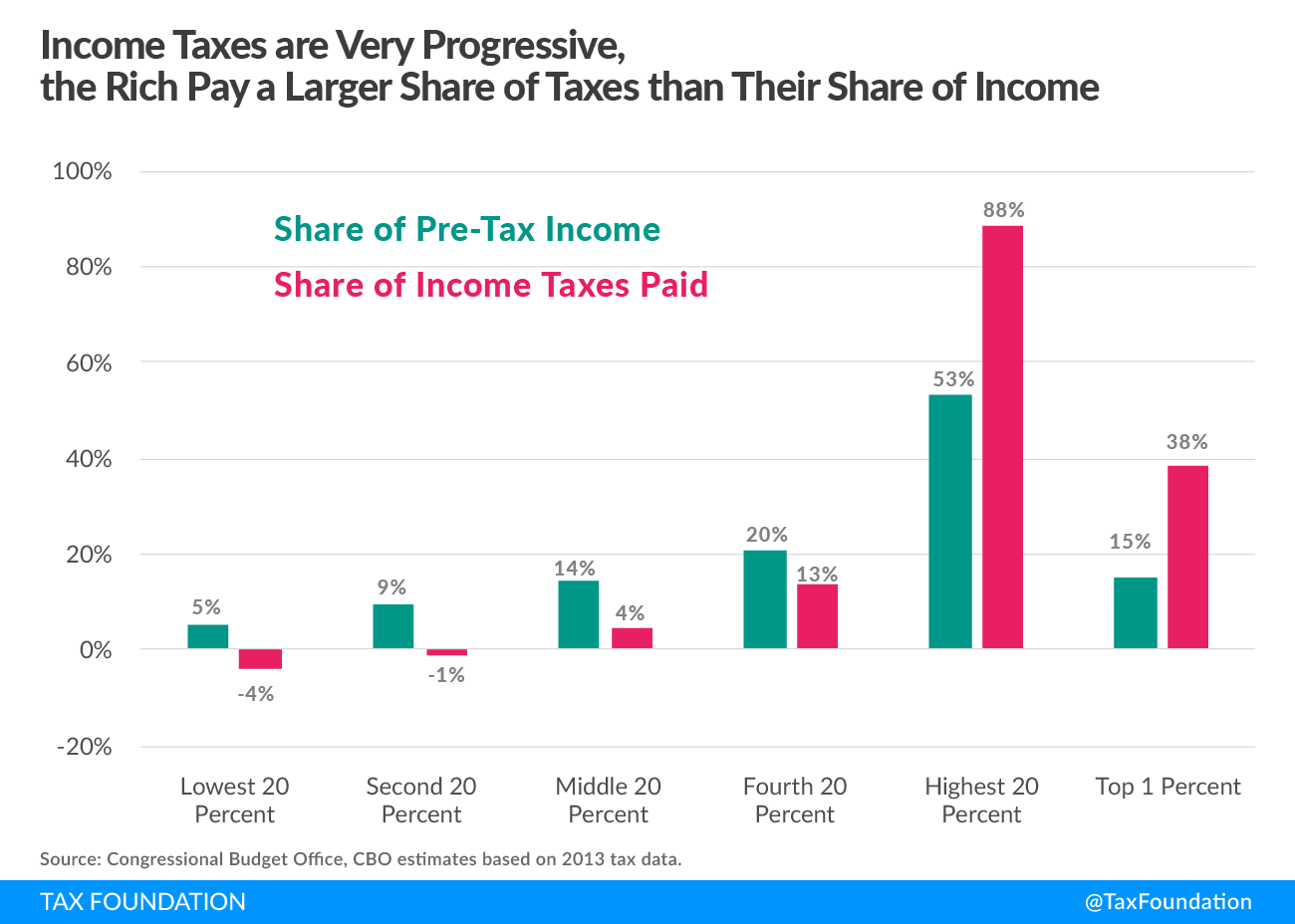

The chart below illustrates how progressive the income tax system is today. The top 20 percent of households—which starts at $117,000 for a two-person household—pay nearly 90 cents of every $1 dollar of federal income taxes. While admittedly these families earn more than 50 percent of the nation’s income, they pay a staggering 88 percent of federal income taxes.

The ratio is even more extreme for the top 1 percent of households. The top 1 percent of households—which starts at $500,000 for a two-person household—earn 15 percent of the nation’s income, but pay 38 percent of federal income taxes. That’s a burden twice their share of income.

By contrast, the bottom 80 percent of households collectively earn 47 percent of national income but pay just 12 percent of federal income taxes. Isolating middle-income households, we can see that they earn 14 percent of the nation’s income but pay just 4 percent of income taxes. The bottom 40 percent of households actually receive more tax credits and refunds from the IRS than they owe in income taxes. Thus, their “income tax burden” is actually negative, as is illustrated in the chart.

Over the past 25 years, distributional concerns and the desire to help working families have led lawmakers to greatly expand the universe of targeted tax credits. Low- and middle-income taxpayers now claim $91.5 billion in nonrefundable tax creditA refundable tax credit can be used to generate a federal tax refund larger than the amount of tax paid throughout the year. In other words, a refundable tax credit creates the possibility of a negative federal tax liability. An example of a refundable tax credit is the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC). s and $90 billion in refundable credits, according to the latest figures from the IRS. The combined $180 billion value of these credits exceeds the amount of money Washington spends on education and transportation combined.

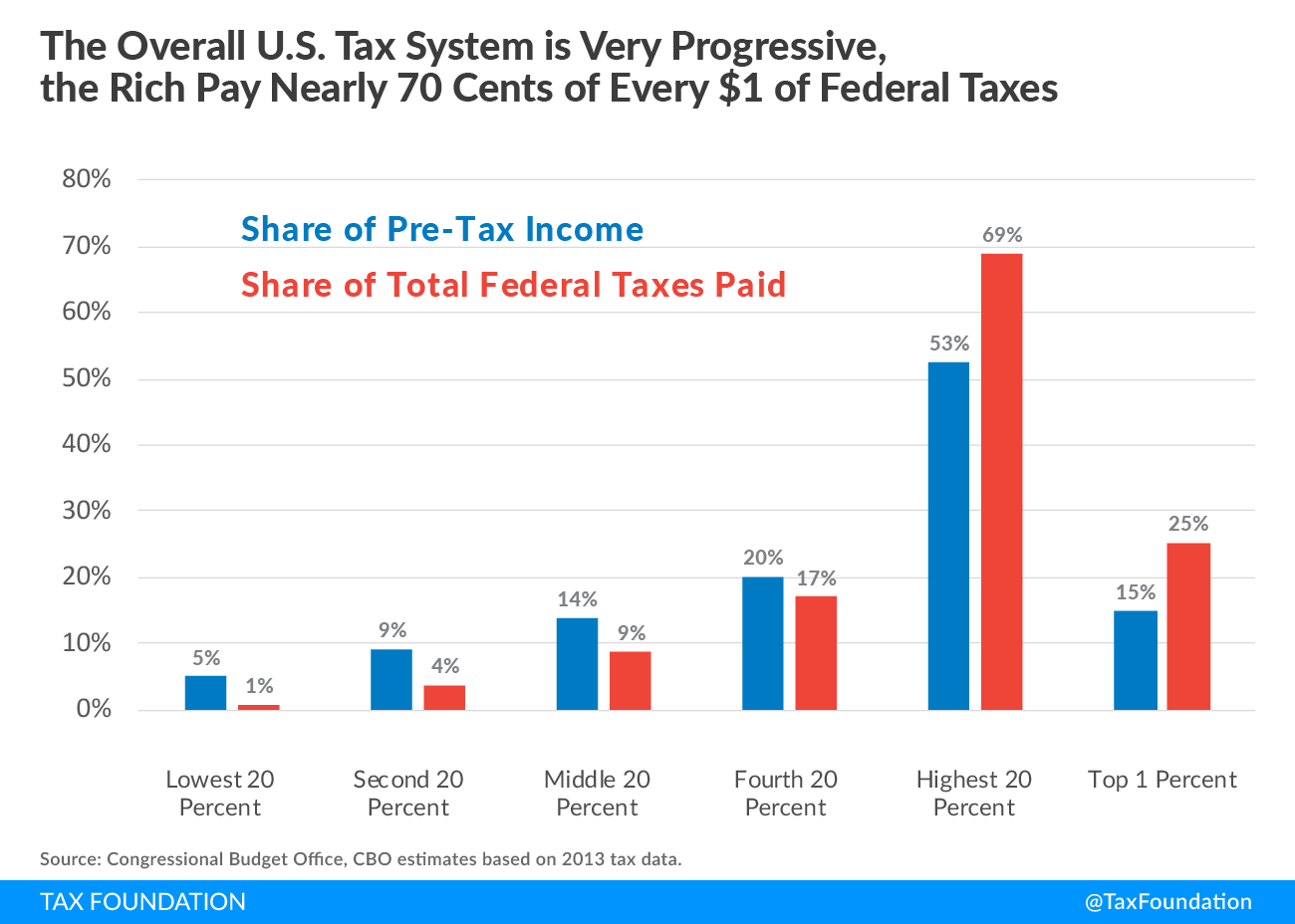

Some argue that while the income tax may be progressive, working families do pay other taxes, such as payroll taxes and excise taxes. However, even if we account for all federal taxes, as the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) did in its recent study “The Distribution of Household Income and Federal Taxes, 2013,” the entire tax system is still highly progressive.

If the tax system were perfectly proportional, each income group would bear a share of the total tax burden equal to its share of the nation’s income. However, the chart shows clearly that even when we account for all federal taxes—even those such as excise and payroll taxA payroll tax is a tax paid on the wages and salaries of employees to finance social insurance programs like Social Security, Medicare, and unemployment insurance. Payroll taxes are social insurance taxes that comprise 24.8 percent of combined federal, state, and local government revenue, the second largest source of that combined tax revenue. es that tend to be more regressive in nature—high-income taxpayers bear a disproportionate share of the total burden.

According to CBO calculations, low-income households earn 5 percent of the nation’s income but pay just 1 percent of all federal taxes. Middle-income households earn 14 percent of national income but shoulder 9 percent of all federal taxes. Even those households in the upper-middle class bear a lower tax burden than their share of national income.

The top 20 percent of households, by contrast, pay nearly 70 cents of every $1 of federal taxes of all kinds—income, payroll, excises, and corporate. As with the income tax, this share is much greater than their share of the nation’s income. The top 1 percent of households, which starts at $500,000 for a two-person household, pay 25 percent of all federal taxes, still significantly more than their 15 percent share of the nation’s income.

Rather than continue to complicate the tax code with more tax credits in order to balance their distributional tables, tax writers would do well to focus their attention on tax policies that will raise real wages and living standards, not just try to lower family tax bills. Many working-class families have not seen a real pay raise in over a decade. An expanded child tax credit may lower their tax bill, but it will not permanently raise their wages or lead to better jobs.

It may seem counter intuitive to many lawmakers, but policies that lower the cost of capital—such as full expensingFull expensing allows businesses to immediately deduct the full cost of certain investments in new or improved technology, equipment, or buildings. It alleviates a bias in the tax code and incentivizes companies to invest more, which, in the long run, raises worker productivity, boosts wages, and creates more jobs. and cutting the corporate tax rate—will do more to boost real wages and living standards than any change in individual tax policy. Targeted tax cuts may play better politically, but pro-growth policies will improve more lives for the long term.

Share