As lawmakers return to Washington, D.C. after the midterm elections, one of their tasks will be addressing technical corrections to last year’s taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. reform law. Issues often arise after legislation is enacted, and Congress can pass “technical corrections” to make laws accurately reflect congressional intent or to fix clerical errors. A letter sent to the Treasury Department in August by several Republican members of the Senate Finance Committee explains how enactment of two provisions in the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) doesn’t align with congressional intent: the “retail glitch” and the timing of a change made to the deduction of net operating losses (NOLs).

Retail Glitch

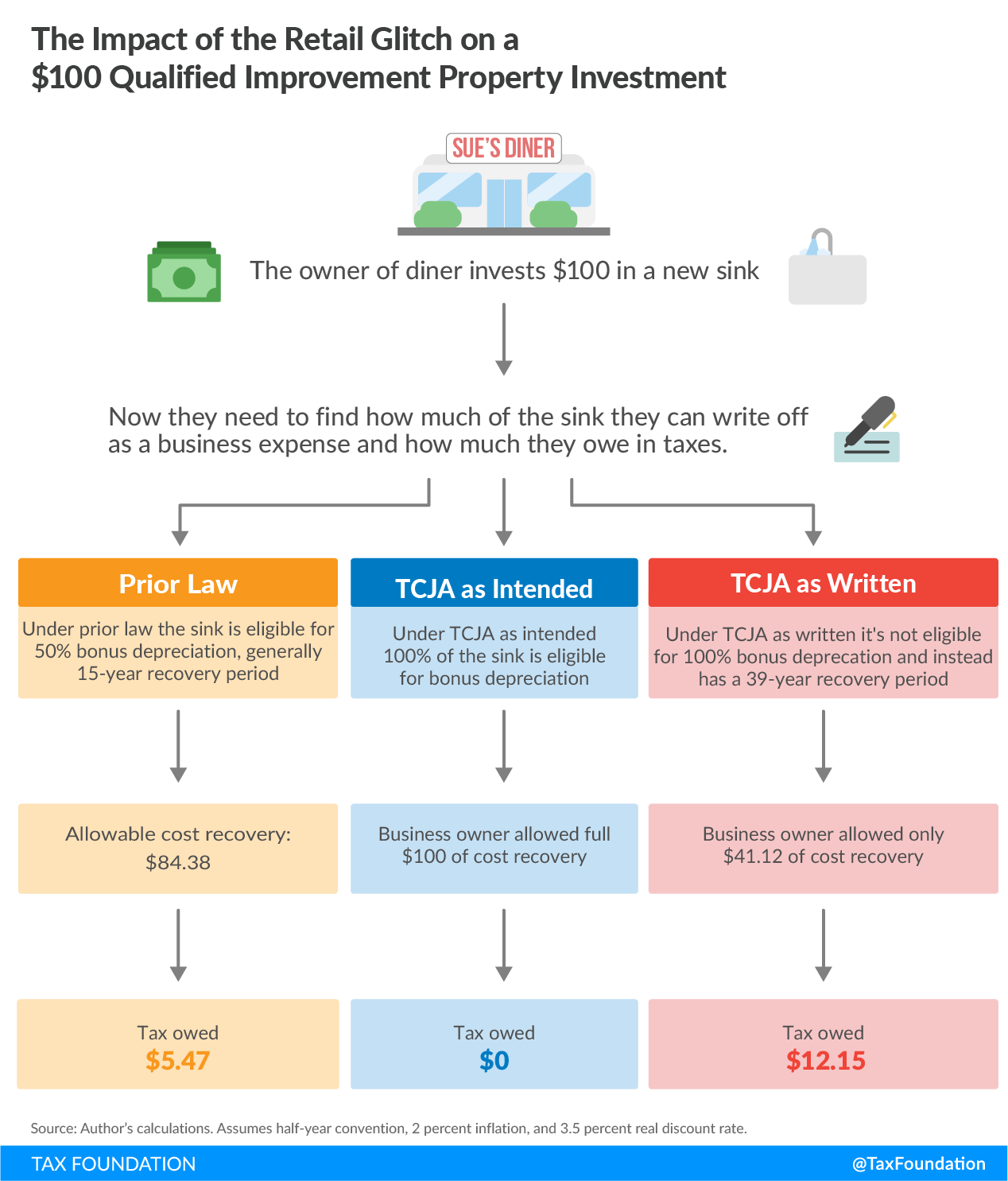

This technical error affects businesses, such as retailers, grocery stores, and restaurants. Due to the error, a certain type of capital investment, called qualified improvement property, receives worse cost recovery treatment than before tax reform, and this is reportedly discouraging business investment and expansion.

Prior to the TCJA, the tax code categorized certain interior building improvements into different classes: qualified leasehold improvement property, qualified restaurant property, and qualified retail improvement property. Assets with lives of 20 years or less were eligible for 50 percent bonus depreciation. While most building improvements are generally depreciable over 39 years, improvements meeting these category definitions were eligible for a 15-year cost recoveryCost recovery refers to how the tax system permits businesses to recover the cost of investments through depreciation or amortization. Depreciation and amortization deductions affect taxable income, effective tax rates, and investment decisions. period and thus eligible for 50 percent bonus depreciation under old law.

The TCJA intended to eliminate the separate definitions in favor of one qualified improvement property definition, designate it as 15-year property, and make it eligible for the new 100 percent bonus depreciationBonus depreciation allows firms to deduct a larger portion of certain “short-lived” investments in new or improved technology, equipment, or buildings in the first year. Allowing businesses to write off more investments partially alleviates a bias in the tax code and incentivizes companies to invest more, which, in the long run, raises worker productivity, boosts wages, and creates more jobs. provision.

Although lawmakers eliminated the separate definitions, the language failed to designate the new definition as 15-year property. By default, it will now receive a 39-year recovery period and thus be ineligible for the new 100 percent bonus depreciationDepreciation is a measurement of the “useful life” of a business asset, such as machinery or a factory, to determine the multiyear period over which the cost of that asset can be deducted from taxable income. Instead of allowing businesses to deduct the cost of investments immediately (i.e., full expensing), depreciation requires deductions to be taken over time, reducing their value and discouraging investment. provision. Additionally, the language contains a typo for a cross reference dealing with the alternative depreciation system.

The glitch increases the cost of capital for investments made by firms. The below graphic illustrates how costly the mistake is.

A fix would mean these businesses no longer face more restrictive cost recovery treatment than before tax reform.

NOL Deduction

This technical error has to do with the timing of new limitations made to deductions for NOLs. The new language states that the TCJA’s limitations apply to NOLs arising in taxable years ending after December 31, 2017; however, congressional intent was that the change would apply to NOLs arising in taxable years beginning after December 31, 2017.

This matters for businesses in which tax years do not align with the calendar year. If a business’s tax year began in mid-2017 and ended in mid-2018, the change would limit its NOLs within that year, instead of the tax year beginning after the change.

NOLs adjust for an asymmetry of corporate income taxes. The corporate income taxA corporate income tax (CIT) is levied by federal and state governments on business profits. Many companies are not subject to the CIT because they are taxed as pass-through businesses, with income reportable under the individual income tax. should tax businesses on their profitability; however, profits can vary widely from year to year. For example, business profitability might be cyclical, meaning in some years the business experiences large gains and in others experiences large losses. The neutrality of the tax code decreases to the extent that it taxes profits in the year they are earned but does not allow for tax benefits when losses occur.

To adjust for this asymmetry, the tax code allows businesses to deduct losses so that businesses are taxed on average profitability. Prior to the TCJA, businesses could “carry back” NOLs up to two years, or “carry over” NOLs up to 20 years to offset their tax liability.

The TCJA disallows NOL deductions to be carried back but allows them to be carried over indefinitely, but it also limits the NOL taken in a tax year. The new limit reduces how much profit NOLs can offset: the lesser of the available NOL carryover or 80 percent of the taxpayer’s pre-NOL deduction taxable income.

Technical corrections bills are common after major legislation, such as the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act. Fixing these drafting errors would make sure provisions accurately reflect congressional intent.

Share this article