A capital gains tax is levied on the profit made from selling an asset and is often in addition to corporate income taxes, frequently resulting in double taxation. These taxes create a bias against saving, leading to a lower level of national income by encouraging present consumption over investment.

Definitions and Rates

Capital assets generally include everything owned and used for personal purposes, pleasure, or investment, including stocks, bonds, homes, cars, jewelry, and art. The purchase price of a capital asset is typically referred to as the asset’s basis. When the asset is sold at a price higher than its basis, it results in a capital gain; when the asset is sold for less than its basis, it results in a capital loss. Although capital gains taxes typically apply to the returns from any capital asset, including housing, U.S. homeowners benefit from a generous exemption for gains resulting from the sale of their primary residence, set at $250,000 for single filers ($500,000 for joint filers).

In the United States, when a person realizes a capital gain, they face a tax on that gain. The tax rates vary depending on two factors: how long the asset was held and the amount of income the taxpayer earns. If an asset was held for less than one year and then sold for a profit, it is classified as a short-term capital gain and taxed as ordinary income. If an asset was held for more than one year and then sold for a profit, it is classified as a long-term capital gain. Table 1 indicates the tax rates for tax year 2025.

2025 Long-Term Capital Gains Tax Brackets

Source: Internal Revenue Service, “Revenue Procedure 2024-40.”

Is Capital Income Tax-Advantaged?

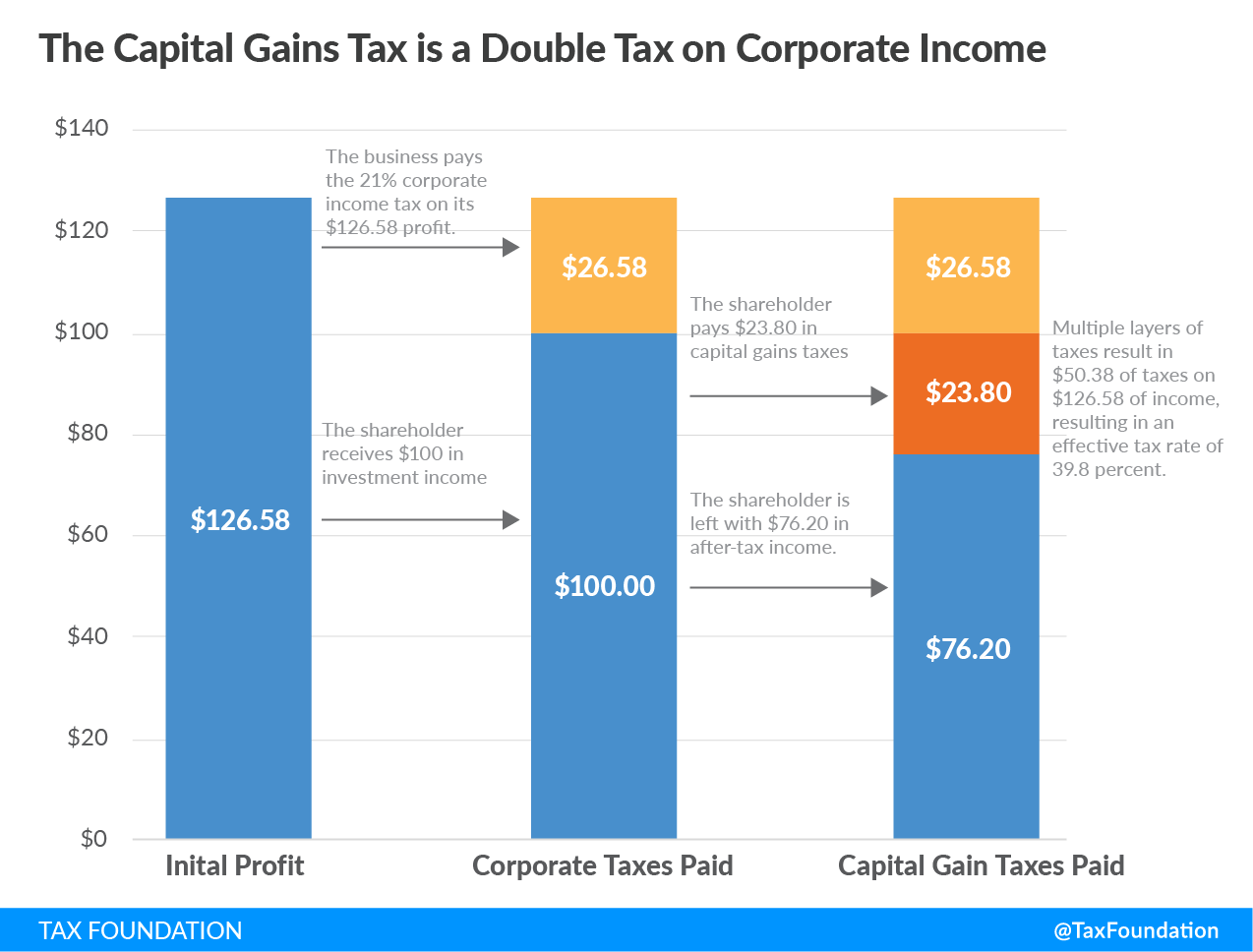

The tax treatment of capital income, such as from capital gains, is often viewed as tax-advantaged. In practice, however, the opposite is true. When capital gains accrue from stock holdings, they represent a second layer of tax, as corporate earnings are already subject to corporate income taxes.

The Impact of a Capital Gains Tax

Capital gains taxes affect more than just shareholders; there are repercussions across the entire economy. When multiple layers of tax apply to the same dollar, reducing the after-tax return to saving, taxpayers are incentivized to consume immediately rather than save. Take the following example from our primer:

Suppose a person makes $1,000 and pays individual income taxes on that income. The person now faces a choice: should I save my after-tax money or should I spend it? Spending it today on a good or service would likely result in paying some state or local sales tax. However, saving it would mean paying an additional layer of tax, such as the capital gains tax, plus the sales tax when the money is eventually used to purchase a good or service. This second layer of tax reduces the potential return that a saver can earn on their savings, thus skewing the decision toward immediate consumption rather than saving. By immediately spending the money, the second layer of tax can be avoided.

The Lock-in or Realization Effect

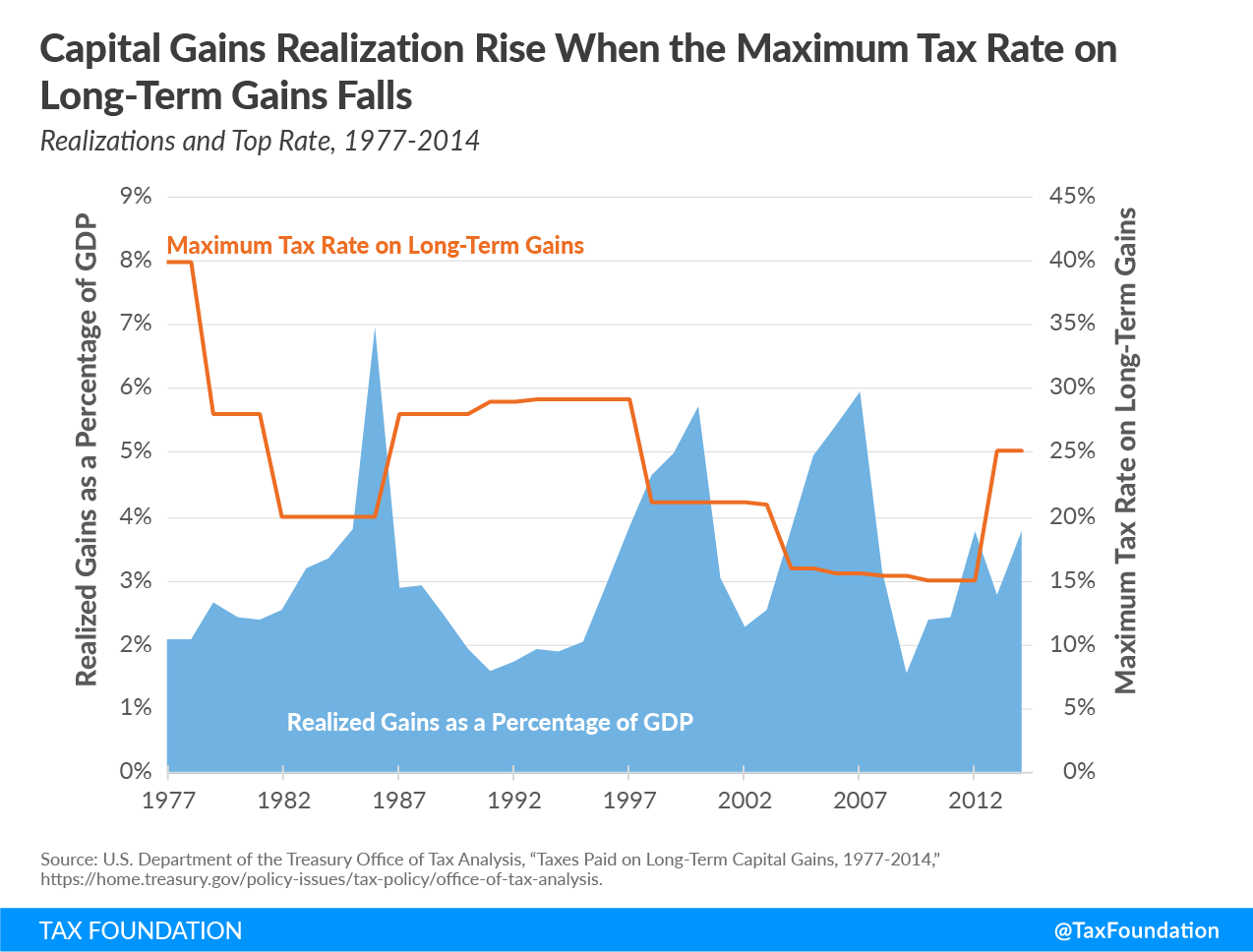

Because capital gains are only taxed when realized, taxpayers can choose when they pay, which makes capital income significantly more responsive to tax changes than other types of income. Higher taxes cause investors to sell their assets less frequently, which leads to less tax being assessed. This is known as the realization or lock-in effect, which is demonstrated in the chart below.

Stay updated on the latest educational resources.

Level-up your tax knowledge with free educational resources—primers, glossary terms, videos, and more—delivered monthly.

Subscribe