The new Social Security Trustees Report has just been released. As always, it contains a wealth of information about the Social Security retirement and disability programs, and Medicare, and is well worth reading. There are two startling facts in the report.

First, this year for the first time since 1982, the combined retirement and disability parts of Social Security (OASDI) is running a deficit, and it will continue to do so throughout the 75-year projection period. Its outlays now exceed its tax revenue and the interest on its trust funds.

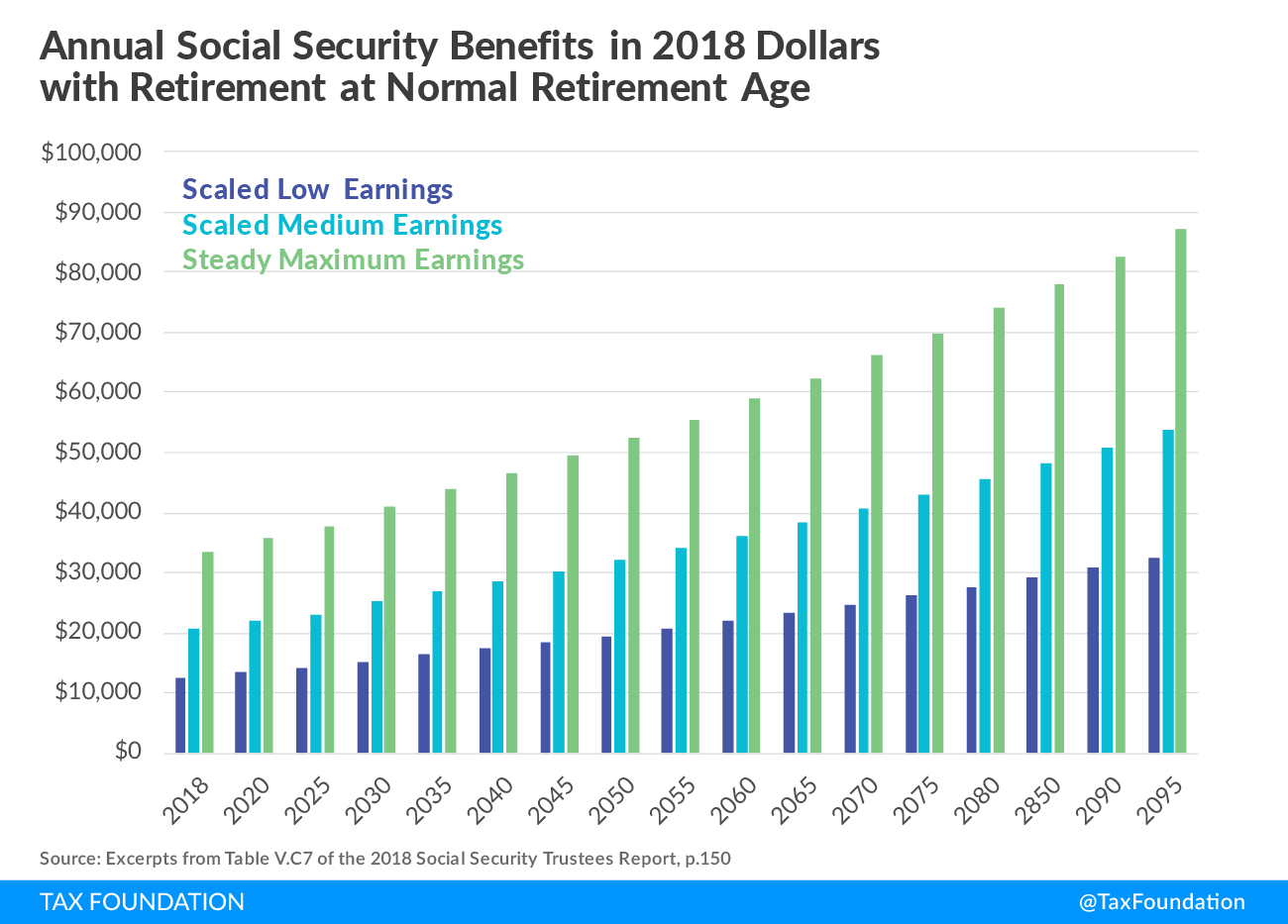

Second, in the face of these impending and growing deficits, the system is promising to raise benefits faster than inflation, promising real benefit increases of over 160 percent over the next 75 years. Upper-income recipients could be getting as much as $87,303 a year, in real 2018 dollars, when they retire in 2095 (and more for married or two-worker couples). These benefits would require more than a four percentage-point hike in the payroll tax for all workers, including lower-paid workers, to balance the system. Instead of remaining a social safety net, focused on keeping the elderly out of poverty, the program is set up to give huge raises to people of all income levels, even as the generations get richer over time. It is threatening to take over the bulk of personal retirement saving and pensions, retarding investment and economic growth, and holding down wages.

The Short-run Financial Issue, and the Sad Truth About the Trust Funds

OASDI is the combined Old Age and Survivors Insurance program, OASI, and the Disability Insurance program, DI. Its current taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. revenue (payroll taxes and income taxation of benefits, plus interest on the trust funds) is now less than its current outlays. The system is still authorized to pay full benefits, up to the OASDI trust fund amounts, so there is no immediate threat to recipients.

The OASI and DI trust funds reflect past surpluses in the system, but those monies were used as they accrued in the past to pay for other government spending. Any outlays currently “covered” by the trust funds require money from other sources. Therefore, using the trust fund authority means that the Treasury will have to borrow or use general revenue to pay a portion of the benefits. Medicare Part A (Hospital insurance or HI) has been running deficits for some time, and has been drawing down its trust fund spending authority for several years. The OASI trust fund spending authority will be used up by 2036, and the DI trust fund by 2032, by which times the Social Security Administration (SSA) will need more spending authority from Congress to continue to pay full benefits. The HI trust fund will be exhausted by 2026, and Medicare will need new funding before then.

An Unrealistic Benefit Formula Drives Perpetual Deficits

Benefits at all levels of income – lower than average, average, and above average or at the maximum covered earnings – are set to grow forever in line with wages. As wages double in real value over time (the actuaries assume this by about 2070), so will promised real benefits. As wages grow by more than 160 percent by the end of the trustees’ planning period in 2095, real benefits will grow by more than 160 percent. For example, single workers earning medium lifetime earnings over their working lives, and who retire today in 2018 at the normal retirement age[i], are projected to receive $20,662 in annual benefits. Medium wage earners retiring in 2095 will receive $53,724 in annual benefits, in 2018 inflationInflation is when the general price of goods and services increases across the economy, reducing the purchasing power of a currency and the value of certain assets. The same paycheck covers less goods, services, and bills. It is sometimes referred to as a “hidden tax,” as it leaves taxpayers less well-off due to higher costs and “bracket creep,” while increasing the government’s spending power. -adjusted dollars, 160 percent more real purchasing power than today’s retiring workers’ benefits, and almost as much as today’s total average family income, just from Social Security. Add 50 percent for a spousal benefit, and double that for a two-worker medium income couple, and it is easy to see why the system’s costs are rising.

Workers who always earned the maximum covered earnings, and who retire this year, are projected to get $33,428 in annual benefits; those who retire in 2095 are projected to receive $87,303, in real 2018 dollars. Add 50 percent for a spousal benefit for a married couple, $130,955, or up to double these numbers for a two-worker household, $174,606. The richest households could receive as much as two or three times the current average household annual income, just from Social Security.

As this is happening, the number of retirees is projected to grow faster than the number of workers, due to demographic changes, unless we significantly boost immigration. The native population fertility rate is well below replacement levels. The replacement rate is an average of 2.1 children per woman over her lifetime. The current fertility rate is under 1.9. The Social Security actuaries are hoping and assuming it rises to 2.0 in their best-guess assumption set, but that may be wishful thinking. The demographics and the promised real benefit increases are why the system is projected to run larger and larger deficits. There are just not enough future workers to pay into the system to maintain that pace of real benefit growth.

Social Security was initially envisioned as one leg of a three-legged stool, the other legs being pensions and personal saving. No one in the 1930s and 1940s envisioned a time when fertility rates would plunge and real incomes would soar. No one worried at that time about Social Security tax rates rising so high as to choke off private saving, nor that the system would take over the bulk of retirement income for a very large portion of the population. It is past time to return the system to its anti-poverty mission, as a true, focused safety net. Let the other two legs of the stool become a ladder that people can climb to a richer retirement by expanding and simplifying tax-friendly retirement accounts, such as Individual Retirement Accounts (IRAs) and 401(k)s.

Fixing the Problem

There is no need for panic, but there is need for action. All that is needed to curb the out-year deficits is to make the real benefits grow more slowly than average wages. To accomplish that, the benefit formula and earnings histories used to set a worker’s benefits when he or she first retires should be prospectively adjusted annually by the growth of prices, instead of wages (or for the lesser of price or wage increases, to be safe), starting a few years hence. This would gradually reduce the “replacement rates” while letting benefits continue to grow in real terms, but at a slower pace. An added year of increase in the normal retirement age to qualify for full benefits would finish the balancing act.[ii] (There are many alternative ways to achieve similar ends, with options to reduce the impact on lower-income workers. See the endnote below.[iii])

Price indexing was recommended to the Senate Finance Committee by the Hsiao Commission in a report to the Committee in 1975.[iv] It warned that wage indexing was unsustainable as slowing birth rates increased the ratio of retirees to workers. President Ford and Congress opted for the more generous wage indexing ahead of the 1976 elections. That decision added over $3 trillion in unfunded future liabilities to the system (now much larger). I presented price indexing to the Greenspan Commission before the 1983 Social Security Amendments, but the Commission focused only on the short run and failed to deal with the distant future. Had price indexing been adopted then, along with the increases in the normal retirement age that were eventually put in place, OASI would now be in balance, and could be maintained that way with one more year’s increase in the normal retirement age going forward.

It is not too late to use these techniques for long-run solvency. They only slow future real benefit growth. They never cut benefits from one cohort to the next (no “notch” issues). They do not punish current retirees. They give ample warning to young people to take advantage of retirement saving plans. They are certainly superior to hitting current retirees with frozen COLAs,[v] or freezing initial benefit growth for new retirees with no warning. However, the gradual changes would take time to bring the system into surplus, and would not cure the deficits projected for the next 30 years or so. The system should be allowed to borrow from the Treasury to deal with these interim deficits, and repay later after the changes begin generating surpluses. That is the price we pay for the 40-year delay in the adoption of the superior indexation mechanisms.

Biting the Bullet Might Be a Tasty Treat

Fixing the system in a manner that encourages more real saving for retirement, and less reliance on an ever-growing tax-transfer system, would do wonders for economic growth and job creation. It would avoid a jobs-destroying payroll taxA payroll tax is a tax paid on the wages and salaries of employees to finance social insurance programs like Social Security, Medicare, and unemployment insurance. Payroll taxes are social insurance taxes that comprise 24.8 percent of combined federal, state, and local government revenue, the second largest source of that combined tax revenue. hike. It would provide additional domestic saving for increasing the U.S. capital stock, which would boost wages, and would increase interest and dividend income for retirees. “Biting the bullet” would be biting a sweet bit of candy.

[i] “Normal retirement age” is defined by law as the age at which one can get full benefits. This was originally 65, but legislation has raised it gradually to 67 for those born after 1959.

[ii] For a more complete analysis of price indexing and the benefit formula, see Stephen J. Entin, “A Simple Change to Restore Social Security Solvency,” Tax Foundation Fiscal Fact No. 478, September 2015, https://files.taxfoundation.org/legacy/docs/TaxFoundation_FF478.pdf.

[iii] There is an infinite variety of ways to reduce the impact of slower growth of benefits on lower-wage workers, if it is desired to give them a raise in relative terms, and make the program focus more on relieving poverty. One method would be to adjust the components of the benefit formula that determines what a retiree gets on first claiming benefits. (This formula for the starting benefit has nothing to do with the annual COLA adjustments of benefits after retirement. Those can be left alone.)

The benefit formula has a set of “bend points” (like brackets in the income tax) with replacement factors (like marginal tax rates, only going down for higher incomes instead of up). To determine benefits, a worker’s monthly earnings are averaged over his or her working life (with past wages adjusted by wage growth to age 60 levels, and by price growth to later years) to get an “average indexed monthly earning,” or AIME. The AIME is then put into the bend point formula to determine the worker’s “primary insurance amount” (PIA). For workers reaching age 62 in 2018, the PIA is 90 percent of the first $895 of monthly earnings, plus 32 percent of additional earnings up to $5,397, and 15 percent of any excess AIME. The sum is then adjusted upwards by inflation to the age the worker retires to produce the first benefit payment the worker gets. (An early retirement penalty, if benefits are taken below normal retirement age, or delayed retirement credit, if one waits beyond normal retirement age, may also apply.) The 2018 formula’s $895 and $5,397 “bend point” boundaries are what are increased each year by increases in average wages, which is why benefits rise in line with wages over time. Price indexing would slow the growth of the bend points, and thereby slow the growth of benefits, as real wage increases in excess of inflation cause the AIME to spill a bit more into the lower replacement factor brackets.

To give a relative raise to the lower-income retirees, Congress could gradually raise the lowest bend point bracket replacement factor of 90 percent to 100 percent, and pay for it by trimming the replacement factors on the second bend point bracket from 32 percent to 30 percent, and the top factor from 15 percent to 12 percent. This could be done over a decade at a fraction of a percent a year.

Alternatively, or additionally, Congress could allow the faster wage growth to continue for a few years, while capping the maximum annual benefit at $35,000 or $40,000 for a single retiree (50 percent for a spouse, and double for a two-worker household), adjusting upwards only for inflation. This would implicitly create a new price-indexed “bend point” with a replacement factor of zero. These levels would not be reached by the highest-income workers for several years, not by the medium-income workers for four decades, and not by lower-income workers until the 2100s. A cap would eventually result in a very flat benefit payout at all income levels. The drawback is that it would make the payroll tax more of a disincentive to work by giving no additional benefits in exchange for the tax on the highest wages.

[iv] See the “Report of the Consultant Panel on Social Security to the Congressional Research Service, Prepared for the Use of the Committee on Finance of the U.S. Senate and the Committee on Ways and Means of the U.S. House of Representatives,” 94th Congress, 2nd Session, August 1976, http://www.socialsecurity.gov/history/reports/hsiao/hsiaoIntro.html.

[v] To see why COLAs are not the issue, see Stephen J. Entin, “Leave the CPI and COLAs Out of the Budget Talks,” Tax Foundation Fiscal Fact No. 345, Dec. 6, 2012, https://files.taxfoundation.org/legacy/docs/ff345.pdf.

Share this article