The House Ways and Means Committee tax reform Blueprint contains a number of important provisions that promote growth. Foremost among them is the immediate expensing (first year write-off) of capital investment outlays. Expensing does more to raise GDP, wages, and employment than any other feature of the Blueprint. Better yet, it is one of the very few taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. changes that boost GDP sufficiently to recover its initial revenue losses and raise revenue over time.

Model analysis

We have used the Tax Foundation Taxes and Growth Model (TAG) to estimate the Blueprint’s effect on GDP and the federal budget. The full package is estimated to increase GDP by about 9 percent over the long term. The expensing provision alone would raise GDP by about 5 percent, more than half the total.[i]

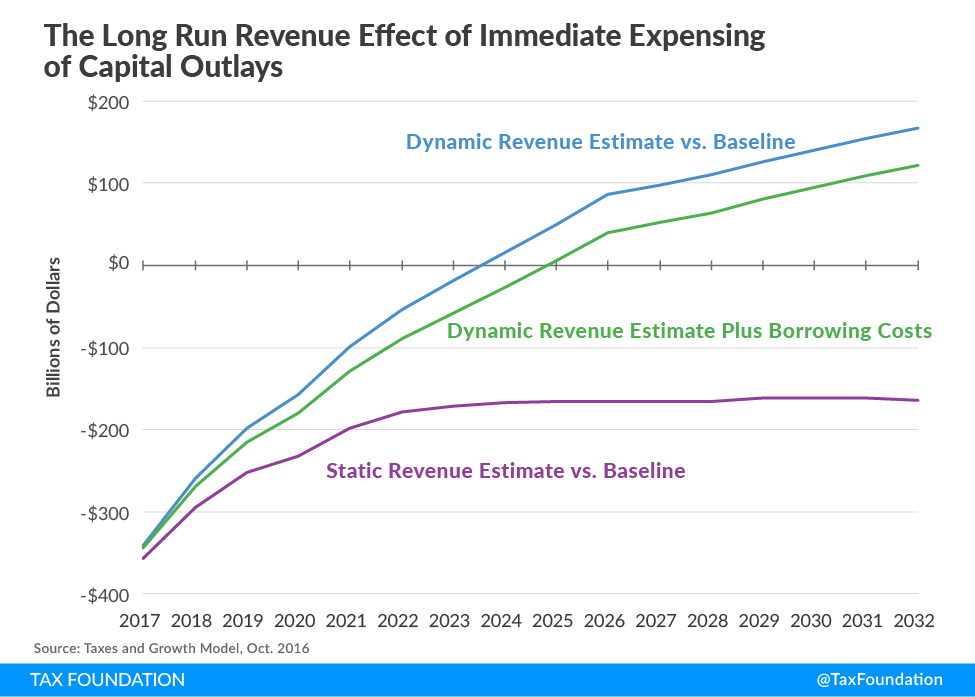

In this blog, we have used the updated October TAG model look at the effect of expensing on a stand-alone basis, without the interactions with the other tax provisions in the Blueprint. (See Chart.)

The TAG model estimates that expensing costs about $2.2 trillion dollars over the ten-year budget window, before accounting for economic growth (static basis). After taking growth into account, the provision costs $1 trillion dollars over the budget window (dynamic basis). The growth of income and employment is projected to increase income and payroll taxes. By year eight, federal revenue rises above the baseline projection of current law. However, in the first eight years, the federal government has higher levels of borrowing. The added debt entails additional annual interest payments. Even after subtracting the projected added interest outlays, by the ninth year, expensing adds enough to the growth of jobs and incomes to raise tax revenue, net of additional borrowing costs, above levels projected under current law. These revenue gains continue to grow beyond the budget window. Over time, the provision results in lower deficits, and a falling ratio of debt to GDP.

Most tax cuts lose revenue, even after accounting for their effects on GDP and job creation.[ii] Expensing is different. It loses tax revenue initially, as new investments are written off in the year they are made, instead of being depreciated over time. However, for each investment project, all the write-off is taken in the first year, with no write-offs taken in later years. Expensing does not increase the total write-off over time for a given amount of investment. In the first few years of expensing, total write-offs exceed those under current law because old investments are still being written off under existing depreciationDepreciation is a measurement of the “useful life” of a business asset, such as machinery or a factory, to determine the multiyear period over which the cost of that asset can be deducted from taxable income. Instead of allowing businesses to deduct the cost of investments immediately (i.e., full expensing), depreciation requires deductions to be taken over time, reducing their value and discouraging investment. rules, in addition to the full expensing of new investments. As the old investments pass through the system, annual write-offs fall back to levels only slightly above those under existing law. From the perspective of the federal budget, expensing is mainly a shift in the timing of write-offs and tax revenue.

Nonetheless, expensing dramatically increases the profitability of capital investment. Business cash flow from each new investment rises sharply in present value, in both the corporate and non-corporate sectors. Write-offs that are delayed for many years lose value due to inflation and the time value of money. Bringing the write-offs closer to the time of the capital outlays, and deferring the associated taxes, lowers the cost of investment and increases the after-tax value of investment projects. It makes profitable many investments that are currently not affordable. The model estimates that expensing increases the nation’s stock of plant, equipment and buildings by nearly $4 trillion, an increase of over 14 percent. The added capital raises worker productivity. Wages are about 4 percent higher, and hours worked about 1 percent higher, representing nearly a million full time equivalent jobs. These income gains from growth generate added federal revenues in the long term.

Conclusion

Expensing is one of the few types of tax changes that can “pay for” itself in higher revenues over time. Of course, the real “pay for” is the significantly higher level of GDP, wages, employment, and household incomes across the country and across the income distribution. The gains to the people’s household budgets far exceed the gains to the federal budget.

[i] See Details and Analysis of the 2016 House Republican Tax Reform Plan available at: http://taxfoundation.orghttps://files.taxfoundation.org/legacy/docs/TaxFoundation_FF516.pdf Numbers cited here may differ slightly due to the stand-alone analysis without the interactions with other provisions of the Blueprint, and to an updating of the model incorporating new GDP forecasts and inflationInflation is when the general price of goods and services increases across the economy, reducing the purchasing power of a currency and the value of certain assets. The same paycheck covers less goods, services, and bills. It is sometimes referred to as a “hidden tax,” as it leaves taxpayers less well-off due to higher costs and “bracket creep,” while increasing the government’s spending power. assumptions.

[ii] Some others come close, such as a corporate rate reduction. A corporate rate cut would recover its revenue loss through growth in other tax payments by the end of the budget window with a small margin to spare. However, other things equal, even a corporate tax rate reduction would have a modest negative budget impact if one includes the effect of the added federal debt accumulated in the first few years, and the associated interest payments. For details, see the forthcoming corporate tax rate blog.

Share this article