As part of its Better Way tax plan, the House GOP has introduced the idea of border adjustment as part of its plan to convert the corporate income taxA corporate income tax (CIT) is levied by federal and state governments on business profits. Many companies are not subject to the CIT because they are taxed as pass-through businesses, with income reportable under the individual income tax. into a destination-based cash flow tax. The border adjustment would eliminate the deduction for imports and exempt the income attributable to exports.

An important aspect of the border adjustment that has been largely ignored is how it would eliminate the type of taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. avoidance that exists under the current corporate income tax. It would also greatly simplify the tax code by eliminating the need for complex anti-avoidance rules that usually accompany territorial tax systemA territorial tax system for corporations, as opposed to a worldwide tax system, excludes profits multinational companies earn in foreign countries from their domestic tax base. As part of the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), the United States shifted from worldwide taxation towards territorial taxation. s.

The problems with the United States’ international system of taxation are well known. The U.S.’s high statutory tax rate encourages companies to relocate profits in foreign jurisdictions to lower their overall tax burdens. In addition, the United States places a residual tax on foreign profits in the United States when those profits are repatriated, which encourages companies to relocate their headquarters (invert) to foreign jurisdictions.

Reforms that would lower the statutory rate and move to a “territorial” tax system would certainly eliminate the incentive to invert and reduce the prevalence of profit shiftingProfit shifting is when multinational companies reduce their tax burden by moving the location of their profits from high-tax countries to low-tax jurisdictions and tax havens. , but U.S. corporate tax baseThe tax base is the total amount of income, property, assets, consumption, transactions, or other economic activity subject to taxation by a tax authority. A narrow tax base is non-neutral and inefficient. A broad tax base reduces tax administration costs and allows more revenue to be raised at lower rates. erosion concerns would still exist

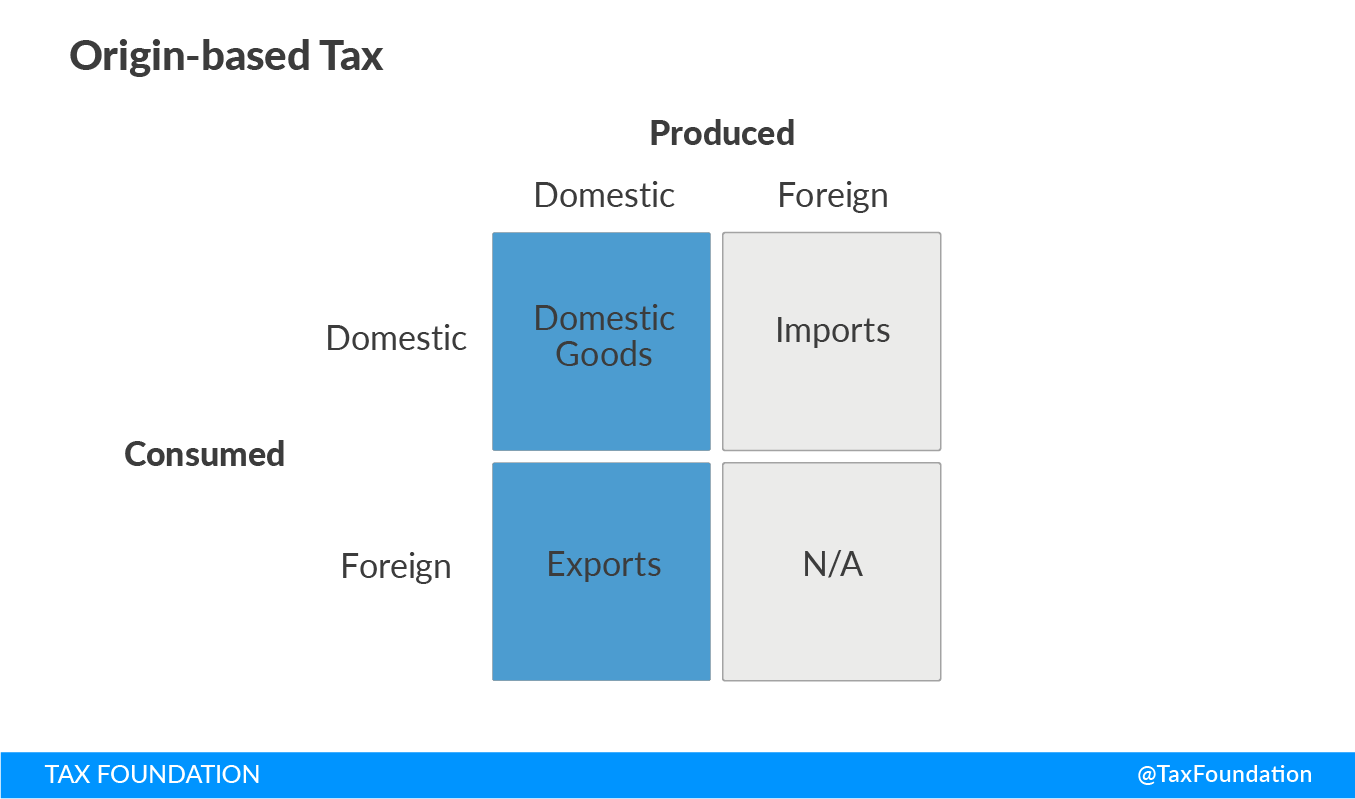

Fundamentally, corporate income taxes are prone to base erosion because they are levied on a base that is extremely hard to measure in today’s globalized world. The corporate income tax can be thought of as a tax on the goods and services produced in an economy regardless of where that good or service is ultimately consumed, or an “origin-based” tax. (In the world of corporate taxation, this type of tax is also referred to as a “source-based” tax).

The location of production can be extremely difficult to figure out. This is because production processes stretch across numerous jurisdictions and include not only physical processes, but also intangible ones that are difficult to price. Take, for example, the production of the movie Star Wars: The Force Awakens. The movie used intellectual property (IP) located in the United States; actors from the United Kingdom and the United States; special effects developed in San Francisco, Singapore, London, and Vancouver; was shot in the UAE, the U.K., Iceland, and Ireland; and tickets for the movie were sold throughout the world.

Companies with multinational production processes take deductions and reporting revenues throughout the world to allocate their profits. As such, it is very hard to determine exactly how much profit should be taxed in a given country.

This ambiguity in the location of productions requires tax jurisdictions to police transactions with strict transfer pricing rules and anti-base erosion regulations to make sure profits are properly allocated. And even with strict rules, sometimes it is just impossible to get it right. Some IP is so unique that there is just no way to know exactly how much royalty payments are supposed to be.

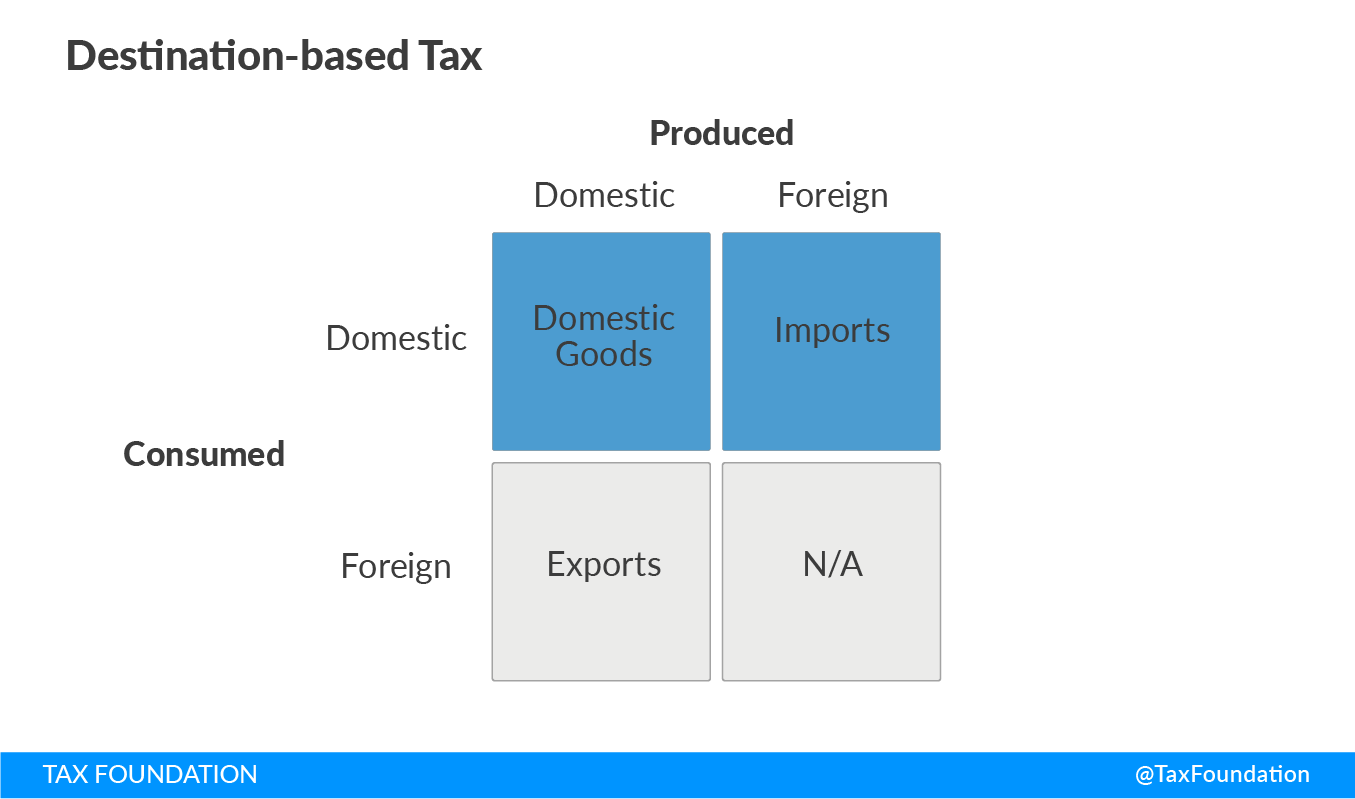

The House GOP Blueprint would move away from an origin- or source-based corporate tax to what is called a “destination-based” tax. A destination-based tax would base the corporate tax on where goods were ultimately sold rather than where they were produced. It would do this by enacting a border adjustment, which would bring imports into the tax base and remove exports.

One of the most attractive features of moving to a destination-based business tax is that its base would be much easier to define than our current corporate tax base. At the end of the day, it is easier to track the single, final transaction between the end consumer and the producer than figure out how much of a good was produced in each tax jurisdiction. In the case of the The Force Awakens, you go from needing to know to what extent a movie, which was made throughout the world, was produced in the United States, to effectively only needing to know how many tickets were sold in the United States.

A consequence of this move to a destination base is that it effectively shuts down the type of base erosion that exists under the current system. Under the current system, companies that produce goods throughout the world have an incentive to artificially shift their production locations by overpricing their deductible production costs in the United States and overstating their taxable revenue in lower tax jurisdictions. Under a destination-based tax, the location of production doesn’t matter, which means that this technique of profit shifting becomes impossible. A destination-based tax ignores the cross-border transactions that make it possible because the cost of imports is no longer deductible and revenue from exports is no longer taxable.

The inability of firms to shift profits also means that a significant portion of the U.S. tax code can be simplified. For one, it would allow for the elimination of transfer pricing regulations on international transactions. Since those transactions no longer matter for domestic tax liability, there is no need to police them. In addition, the elimination of current law profit-shifting techniques also eliminates the need for other complex anti-base erosion provisions such as Subpart F, which prevents companies from using highly mobile income to avoid U.S. taxation.

This doesn’t mean a destination-based tax is immune from complexity and tax avoidance. Sometimes it is challenging to figure out exactly where a customer is located. This is especially true looking at services and digital goods. This is something that the OECD has been working on for many years in the context of destination-based value-added taxes as part of their “BEPS” initiative. Addressing these concerns in the final legislation is important.

However, the challenges and complexities with a destination-based system are arguably much less severe than those in an origin-based system.

By no means is a destination-based tax system the only way to reform the U.S. tax code. The U.S. could move in the direction of the European countries that have enacted “territorial” tax systems over the last decade. But as stated above, origin-based corporate taxes are prone to tax avoidance. That’s why nearly every developed country with a territorial corporate tax has strict anti-base erosion provisions.

Those that would rather see a reform without the border adjustment will need to take seriously ideas such as the Dave Camp tax reform proposal’s “Option C” and former President Obama’s worldwide minimum tax as options to prevent international tax avoidance.

The problems with the United States’ international system of taxation are well known. While moving to a territorial tax system and lowering the rate would mitigate the issue with inversions and income shifting, problems would remain. Fundamentally, the corporate income tax is prone to tax avoidance because it is levied on a hard-to-define base. A move to a destination-based business tax would reduce the scope of tax avoidance because its base, domestic sales, is much easier to track. By no means would a destination-based tax avoid all complexities of a modern tax system and tax avoidance, but it is an improvement over the current system of international taxation.

Share