In 2017—as part of the TaxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA)—Congress limited the mortgage interest deductionThe mortgage interest deduction is an itemized deduction for interest paid on home mortgages. It reduces households’ taxable incomes and, consequently, their total taxes paid. The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) reduced the amount of principal and limited the types of loans that qualify for the deduction. (MID) by reducing what can be deducted to interest paid on the first $750,000 in principal value, down from $1 million. The decision to curtail the deduction’s limit by 25 percent was partly due to budgetary constraints imposed by “reconciliation” in the Senate to conform to tax and spending levels.

Whatever the motivation behind the reform, a smaller deductible amount would increase revenue and reduce the beneficial tax treatment provided for debt-financed owner-occupied housing (while curtailing a tax expenditureTax expenditures are a departure from the “normal” tax code that lower the tax burden of individuals or businesses, through an exemption, deduction, credit, or preferential rate. Expenditures can result in significant revenue losses to the government and include provisions such as the earned income tax credit (EITC), child tax credit (CTC), deduction for employer health-care contributions, and tax-advantaged savings plans. ).

As various versions of the TCJA passed through the House and Senate, certain proponents of maintaining the deduction at $1 million argued that limiting it would harm the mortgage market and hurt the middle class—by creating a less stable housing market, reducing access to homeownership, and thus leading to fewer homeowners.

Yet, by any measure, the deduction—either prior to TCJA or in its aftermath—does not result in more taxpayers becoming homeowners. Instead, it is among the largest tax expenditures in the code, serving as an indirect subsidy to wealthy taxpayers to finance purchasing a larger home.

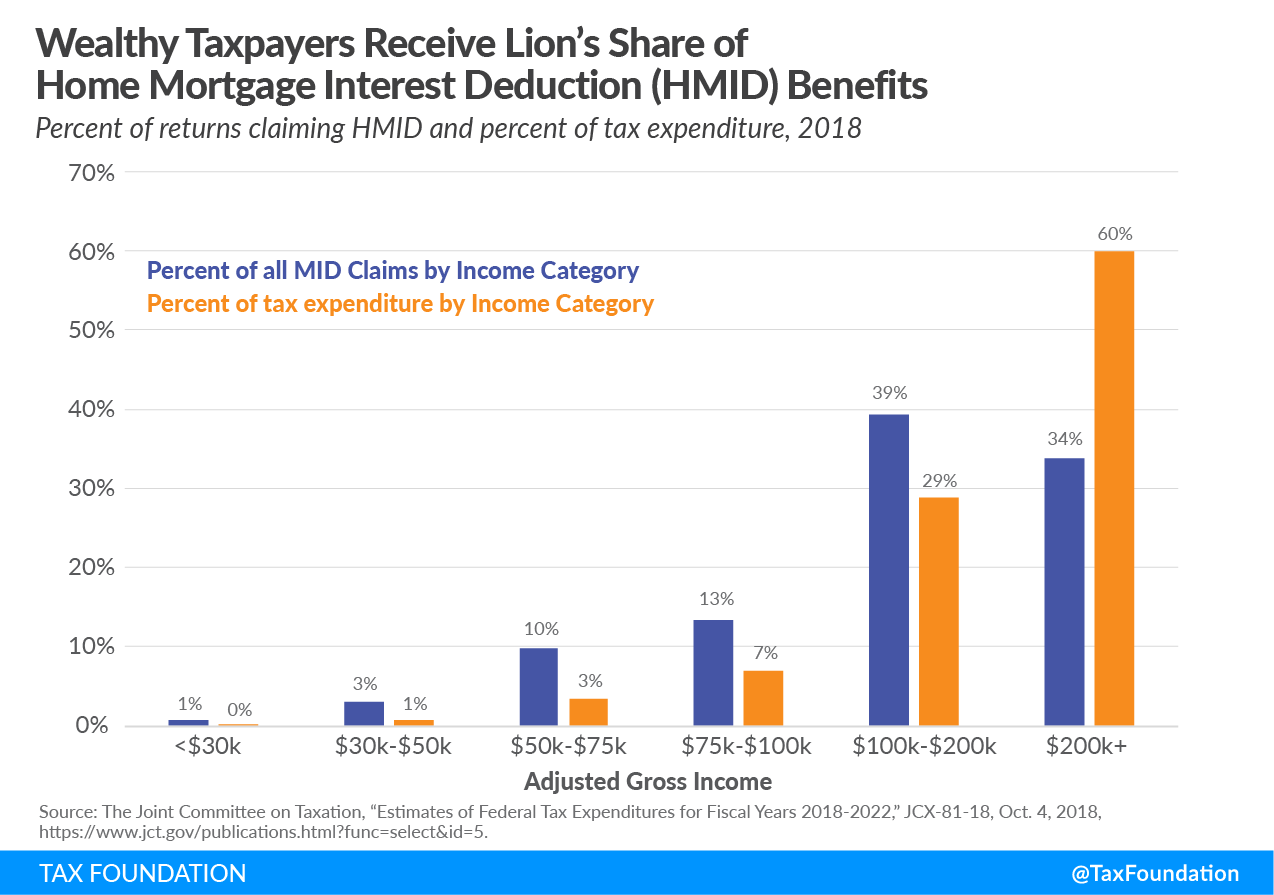

Because the TCJA increased the value of the standard deductionThe standard deduction reduces a taxpayer’s taxable income by a set amount determined by the government. It was nearly doubled for all classes of filers by the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) as an incentive for taxpayers not to itemize deductions when filing their federal income taxes. , fewer filers itemized their deductions, shrinking the eligible pool of taxpayers who could apply for the MID’s benefits. Filers who take the standard deduction—by far the majority of the taxpaying population both before and after the TCJA was passed—cannot claim any part of the mortgage interest deduction. In the first year the TCJA’s changes went into effect, the deduction primarily reduced the cost of debt-financed property for those who make over $100,000 (see Figure 1).

Consider three myths about the deduction, each debunked by the data:

Myth 1: Reducing the deduction would result in less mortgage participation overall

According to the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, since the TCJA was passed in December 2017, Americans have increased their mortgage debt for one-to-four family residences. Despite the tighter limit on principal value eligible for the mortgage interest deduction, total mortgage debt for family dwellings has gone up, not down, as some predicted. This means more Americans are taking out mortgages to finance their homes, likely due in part to historically low interest rates. While we do not have do not have the ability to compare current mortgage participation data (post-TCJA) with what might have been the case had the deduction been retained at its pre-TCJA levels, we can see that mortgage participation has not fallen in the years following the tax change.

Myth 2: Reducing the deduction would hurt the middle class

As part of its policy design, the MID only benefits taxpayers who itemize on their returns—and that tends to be wealthier taxpayers. Prior to the TCJA, about 30 percent of filers itemized, and after the TCJA, about 10 percent itemize. The remaining filers find it more advantageous to take the standard deduction. The majority of tax filers prior to the TCJA did not take the MID and even fewer take it now.

| Number of Returns (Thousands) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Income Category | 2017 | 2018 | Percent Change |

| Less than $10,000 | 178 | 65 | -63.5% |

| $10,000 to $20,000 | 517 | 154 | -70.2% |

| $20,000 to $30,000 | 933 | 237 | -74.6% |

| $30,000 to $40,000 | 1,595 | 410 | -74.3% |

| $40,000 to $50,000 | 2,222 | 635 | -71.4% |

| $50,000 to $75,000 | 6,683 | 2,136 | -68.0% |

| $75,000 to $100,000 | 6,622 | 2,442 | -63.1% |

| $100,000 to $200,000 | 17,959 | 6,513 | -63.7% |

| $200,000 to $500,000 | 8,207 | 4,185 | -49.0% |

| $500,000 to $1,000,000 | 1,089 | 791 | -27.4% |

| $1,000,000 and over | 509 | 444 | -12.8% |

|

Source: The Joint Committee on Taxation, “Tables Related to the Federal Tax System as In Effect 2017 Through 2026”; author’s calculations. |

|||

The benefits of the deduction continue to primarily flow to higher-earning, itemizing taxpayers. In 2018, filers with more than $100,000 in income constituted 73 percent of all MID claims and 89 percent of the MID’s benefits (Figure 1).

Myth 3: Reducing the deduction will reduce the homeownership rate

Many economists and housing policy scholars agree that the deduction has almost no effect on homeownership rate. As my colleague Erica York pointed out in 2017: “The MID primarily benefits upper-income taxpayers, has no discernable positive impact on promoting homeownership, and likely contributes to housing price instability. As the House and Senate conferees begin negotiations, capping the ‘accidental deduction’ should not be a difficult difference to resolve.”

Furthermore, other developed countries, such as Canada, do not include a deduction for mortgage interest in their code, but their homeownership rate remains comparable to the United States.

Reforming MID: More to Be Done

The TCJA’s changes to the mortgage interest deduction increased code neutrality by reducing a major bias toward itemized filers with more expensive homes. Yet, more work remains to be done. Reforming the deduction into a credit—or eliminating it altogether—comes with its own advantages and drawbacks. There are no easy answers that hold all filers harmless. However, in the long run, policymakers should strive to create a tax policy landscape with broad bases (i.e., few exceptions and exclusions) and low rates.

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

Subscribe