Full expensingFull expensing allows businesses to immediately deduct the full cost of certain investments in new or improved technology, equipment, or buildings. It alleviates a bias in the tax code and incentivizes companies to invest more, which, in the long run, raises worker productivity, boosts wages, and creates more jobs. of capital investments is probably the single most significant taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. change lawmakers could make to encourage economic growth. By removing nearly all barriers to investment from the business tax code, full expensing could grow the long-run size of the U.S. economy by 4.2 percent, which would lead to 3.6 percent higher wages and 808,000 full-time jobs. In fact, we find that moving to full expensing for corporations would have twice the impact on the U.S. economy as a simple corporate tax rate cut.

However, the biggest challenge for proponents of full expensing is the “sticker shock” of the policy: the federal revenue loss that would accompany a move to full expensing. For instance, last June, the Tax Foundation estimated that moving to full expensing would reduce federal revenue by $2.2 trillion over ten years, on a static basis. That’s a big number, and it naturally gives lawmakers pause.

That said, the ten-year revenue score for full expensing likely overstates the true cost of the policy. There are a few reasons why the ultimate cost of full expensing is much less than $2.2 trillion:

- Full expensing is often proposed in the context of tax reform plans that would lower marginal tax rates on U.S. businesses. Importantly, the lower marginal tax rates on businesses are, the less that full expensing will reduce federal revenue. For instance, moving to full expensing costs about $700 billion less over ten years under a 20 percent corporate tax rate than under a 35 percent corporate tax rate.

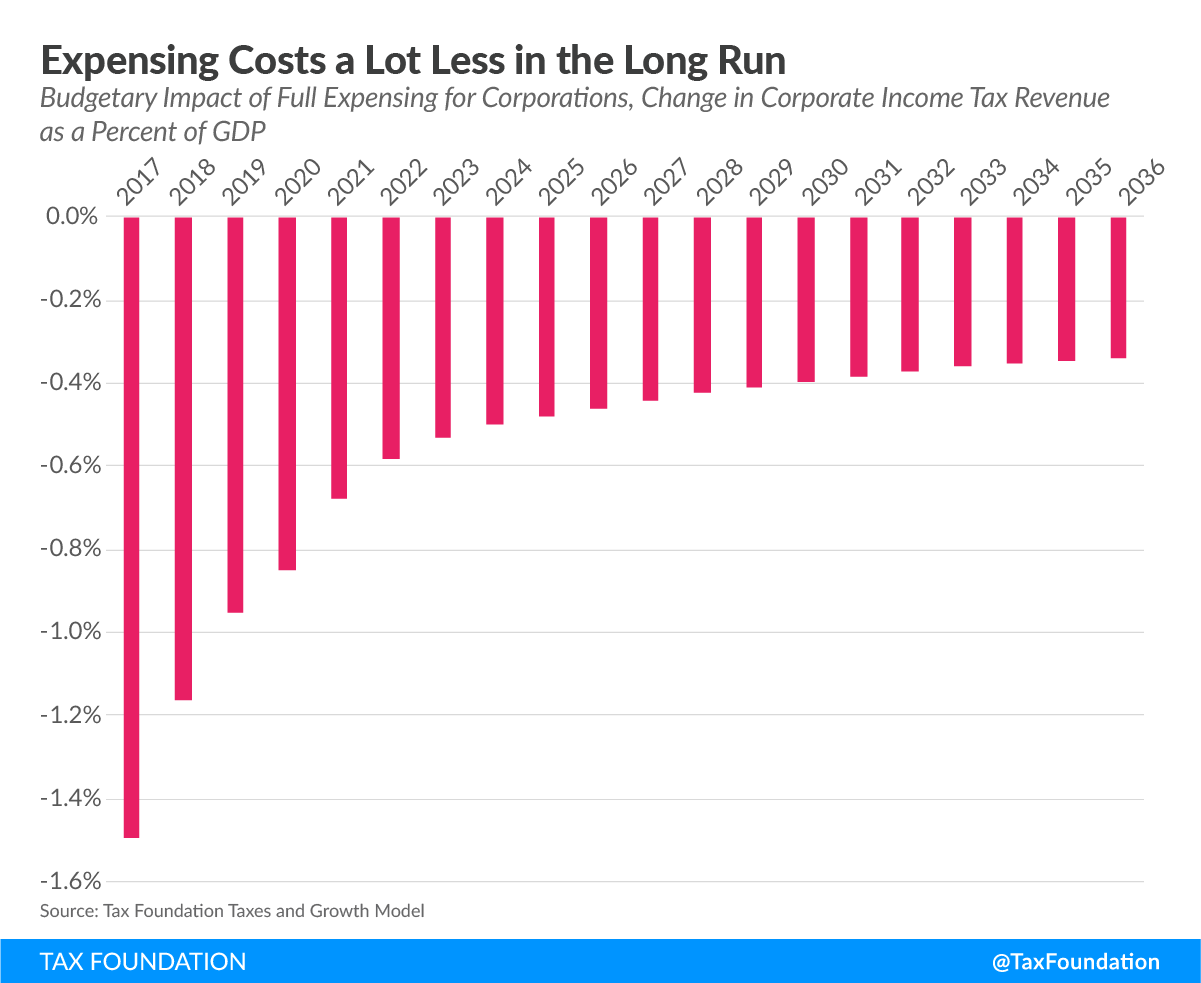

- Much of the ten-year revenue loss from full expensing comes from one-time transition costs. These transition costs nearly disappear by the second decade of the policy. As a result, full expensing costs much less in the long run than the short run. One illustration of this: full expensing for corporations would reduce static federal revenue by 1.5 percent of GDP in the first year of the policy, but only by 0.4 percent of GDP in the tenth year.

- When looking at the cost of full expensing in the long run, the policy is much less costly than one might expect. In fact, moving to full expensing for corporations costs less than cutting the corporate tax rate to 25 percent in the long run, on a static basis.

- It is likely that the Joint Committee on Taxation will have a lower static score for the cost of full expensing than the Tax Foundation’s. Given that the JCT is Congress’s official scorekeeper for tax policy, this is important to keep in mind.

- Finally, it is likely that moving to full expensing would grow the U.S. economy significantly. The additional growth would increase the size of the individual income and payroll taxA payroll tax is a tax paid on the wages and salaries of employees to finance social insurance programs like Social Security, Medicare, and unemployment insurance. Payroll taxes are social insurance taxes that comprise 24.8 percent of combined federal, state, and local government revenue, the second largest source of that combined tax revenue. bases, recouping a portion of the initial revenue loss.

What is full expensing?

Under the current tax code, when a business makes a capital investment – such as purchasing machinery, equipment, and buildings – it is not allowed to deduct the full cost of that investment immediately. Instead, businesses are required to deduct the cost of their capital expenditures over long periods of time, taking “depreciationDepreciation is a measurement of the “useful life” of a business asset, such as machinery or a factory, to determine the multiyear period over which the cost of that asset can be deducted from taxable income. Instead of allowing businesses to deduct the cost of investments immediately (i.e., full expensing), depreciation requires deductions to be taken over time, reducing their value and discouraging investment. deductions” over schedules ranging from three years to 39 years.

Not only is the current system of tax depreciation quite complicated, but it also serves as a significant barrier to business investment. Because businesses do not value deductions far in the future as much as deductions in the present, requiring a business to deduct the cost of an investment over time means that the business is less likely to undertake the investment in the first place.

As a result, many lawmakers have advocated for full expensing: a system where businesses would be able to deduct the full cost of all their investments in the year they are purchased. Moving to full expensing would remove the bias against investment from the business tax code and would significantly lower the cost of capital, encouraging businesses to invest and create jobs.

The cost of full expensing depends on the business tax rate

Because full expensing would allow businesses to deduct a greater share of their capital investments, a move to full expensing would lead to more deductions taken by businesses overall. This would decrease businesses’ taxable incomeTaxable income is the amount of income subject to tax, after deductions and exemptions. For both individuals and corporations, taxable income differs from—and is less than—gross income. , leading to lower federal tax collections.

When lawmakers enact a policy that increases the amount of deductions taken by businesses, the resulting federal revenue loss will depend on what marginal tax rateThe marginal tax rate is the amount of additional tax paid for every additional dollar earned as income. The average tax rate is the total tax paid divided by total income earned. A 10 percent marginal tax rate means that 10 cents of every next dollar earned would be taken as tax. s businesses face. For instance, under the current 35 percent corporate rate, an additional $100 of deductions taken by a corporation would reduce federal revenue by $35. But if the corporate tax rate were 20 percent, then a corporation’s choice to take $100 more in deductions would only decrease federal revenue by $20.

As a result, the cost of full expensing depends entirely on the tax rates faced by U.S. businesses. For instance, in a world with a 20 percent corporate rate, full expensing would decrease federal revenue by about $700 billion less over ten years than under the current 35 percent corporate rate.

This is important, because full expensing is often proposed in the context of tax plans that would also lower the statutory tax rate on U.S. businesses. For instance, the House GOP tax plan proposes full expensing alongside a 20 percent corporate tax rate and a 25 percent top tax rate on pass-through businessA pass-through business is a sole proprietorship, partnership, or S corporation that is not subject to the corporate income tax; instead, this business reports its income on the individual income tax returns of the owners and is taxed at individual income tax rates. es. Against these rates, full expensing would cost much less than it would under the current tax code.

When the Tax Foundation scored the House GOP tax plan, we had to make a choice about what order to “stack” the provisions in. Because we scored the fiscal cost of full expensing before scoring the cost of a lower corporate rate, our $2.2 trillion score was essentially an estimate of how much it would cost to move to full expensing under current business tax rates.

But it seems that lawmakers are already set on significantly lowering the marginal tax rate on U.S. businesses, and may be considering whether to move to full expensing as well. In this case, it would make more sense to think about the fiscal cost of full expensing under reduced business tax rates – which would be significantly lower.

The long-run cost of full expensing is much less than the initial cost

Moving to full expensing would lower federal revenue in the long run, but it would also create large, one-time, transitional revenue losses. It is important to disentangle these two effects on federal revenue to understand the true fiscal impact of the policy.

Because full expensing would increase the present value of deductions for capital investment, it would permanently reduce business taxable income. This would cause a long-run drop in federal tax collections.

However, there is an additional transitional cost associated with moving from a system of depreciation to full expensing. Proposals for expensing typically allow companies to continue to write off the cost of prior years’ investments according to the previous law’s depreciation schedule. This means that if a company purchased a five-year asset the year before expensing was enacted, it would still be able to deduct the remaining four years as it would have if the law never changed.

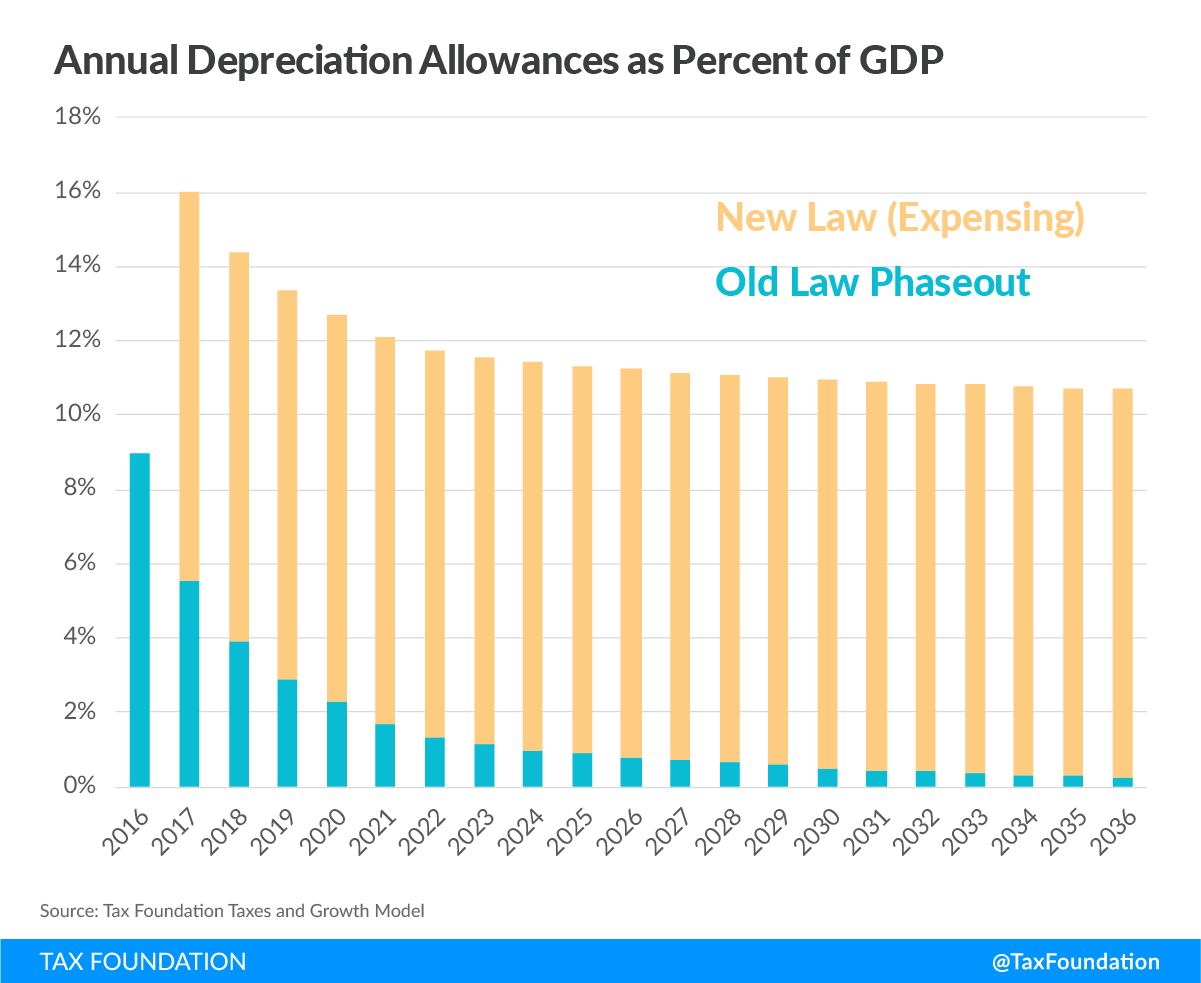

We illustrated this effect for all corporations using the Tax Foundation’s tax model. We imagine a scenario where Congress enacts full expensing in 2017. In the chart below, we show the amount of depreciation deductions that corporations would receive, as a percent of GDP, during a transition to full expensing.

In 2016, before expensing is enacted, corporations’ depreciation deductions under MACRS (the current depreciation system) total about 9 percent of GDP. These deductions are for capital investments companies made in 2016 and from investments made in previous years that continue to get written off.

When expensing is enacted in 2017, corporations are able to deduct the full cost of all their new investments – but also continue to deduct investments they made in prior years, according to each investment’s schedule. This includes short-lived machines that were purchased the previous year, as well as long-lived assets such as buildings that might have been purchased 20 years earlier. In total, in 2017, corporations take deductions equaling 16 percent of GDP –10.4 percent from new investments, and 5.6 percent from old investments.

Over time, the amount companies deduct on an annual basis declines, as old investments are fully written off. From 2018 to 2022, corporate deductions for capital expenses fall quickly, from 14 percent of GDP to just under 12 percent of GDP. By 2036, most of the old investments have been fully written off and deductions fall to about 10.5 percent of GDP.

Overall, corporations see a bulge in deductions in the first few years after the enactment of full expensing, which substantially reduces their taxable income. However, eventually, investments made under the old law are completely written off. At this point, deductions under expensing for corporations settle at around 10 percent GDP, which is slightly larger than they are under current law.

This bulge in investment deductions substantially reduces corporate taxable income and tax revenue in the first years after expensing is enacted. However, just as the number of deductions taken decline over time, so too does the cost of expensing.

Below, we show what annual revenue from the corporate income taxA corporate income tax (CIT) is levied by federal and state governments on business profits. Many companies are not subject to the CIT because they are taxed as pass-through businesses, with income reportable under the individual income tax. would look like from 2017 to 2036 if expensing were enacted. The chart below looks much like the mirror image of the chart above showing corporate deductions. This is because, under full expensing, as corporate deductions increase substantially and then taper off, corporate tax revenue would decline substantially and then rebound.

In the first year after enactment of expensing, corporate revenues fall by 1.5 percent of GDP. But as time goes and the number of deductions taken by corporations declines, the cost of expensing declines. By the tenth year (2026), the annual cost of expensing is a little more than 0.4 percent of GDP, less than 31 percent of the first year’s cost. By the time you get to 2036, the annual cost of expensing is about 0.35 percent of GDP, less than one-quarter of the first-year cost.

This pattern of revenue interacts with the ten-year budget window used by Congress in an interesting way. The most costly years in the transition to full expensing are years 1 through 5. When we show that expensing costs about $2.2 trillion in the first ten years, this includes those first five years, in which expensing greatly reduces federal revenue, but not years 11 through 15, in which expensing has a much lower cost. In a sense, measuring the cost of expensing over the budget window is unideal.

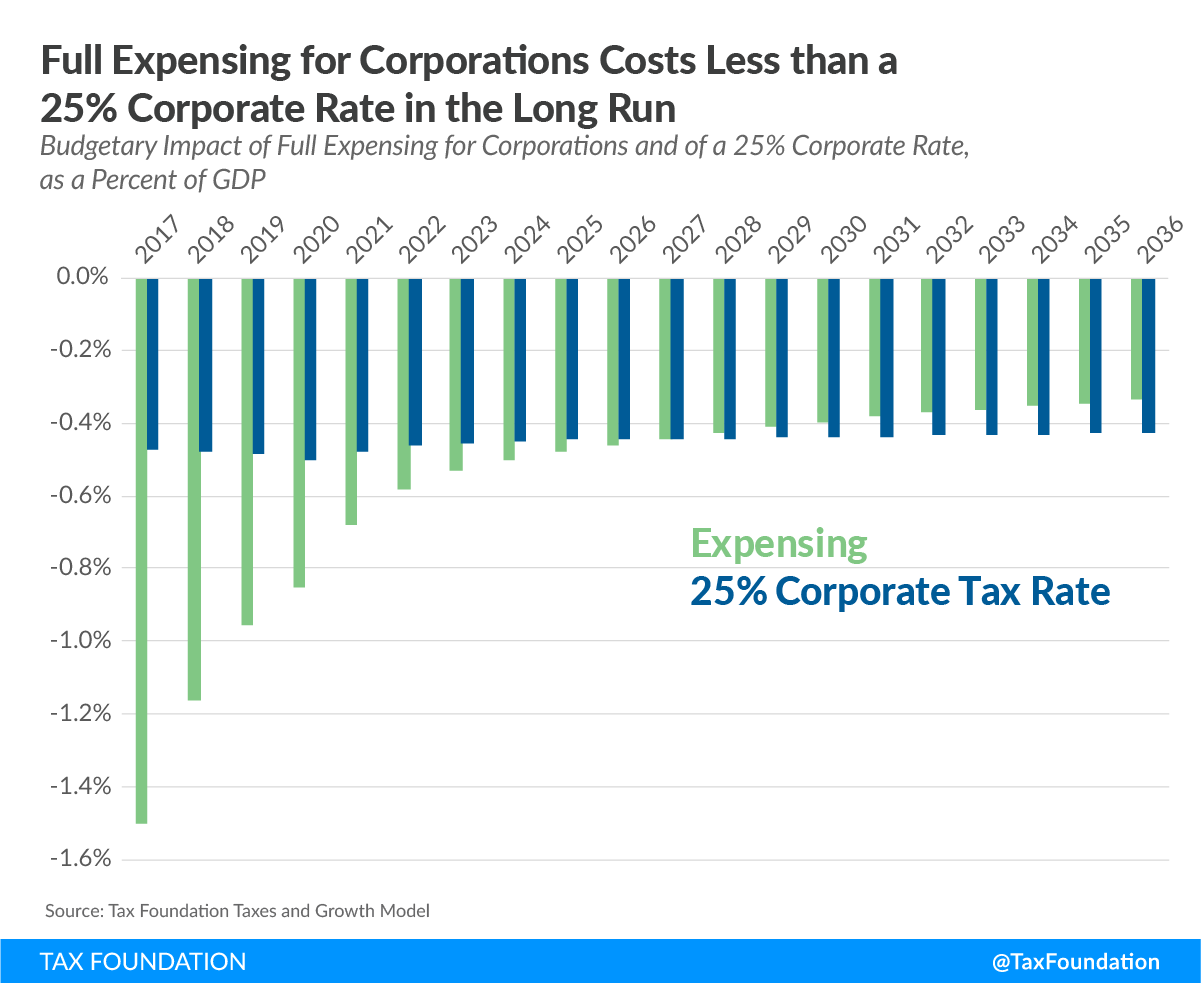

In the long run, full expensing costs less than a 25 percent corporate rate

Something interesting happens when you look at expensing’s cost beyond the budget window. Many tax provisions that look cheaper than expensing actually end up costing more in the long run.

Take, for example, the cost of a 25 percent corporate income tax rate compared to the cost of full expensing for corporations. Expensing has significant upfront costs that a 25 percent corporate rate does not have. As a result, expensing will look like it costs twice as much as a 25 percent corporate rate in the first decade. However, the cost of full expensing declines drastically over time, but the cost of a 25 percent corporate is consistent through time.

As a result, the cost of full expensing for corporations is less than that of a 25 percent corporate tax rate in the long run.

Congressional scorekeepers may have a lower score for the cost of full expensing

To determine how the budgetary cost of full expensing will figure into the tax reform debate on Capitol Hill, it is also instructive to examine how the policy might be analyzed by the official tax scorekeeper for Congress, the Joint Committee on Taxation. There is reason to believe that, if JCT estimated the cost of full expensing, it would find a lower static cost than the Tax Foundation’s score.

In 2015, the JCT analyzed the cost of a similar policy to full expensing, bonus depreciationBonus depreciation allows firms to deduct a larger portion of certain “short-lived” investments in new or improved technology, equipment, or buildings in the first year. Allowing businesses to write off more investments partially alleviates a bias in the tax code and incentivizes companies to invest more, which, in the long run, raises worker productivity, boosts wages, and creates more jobs. . Specifically, the JCT estimated that making bonus depreciation into permanent law would reduce federal revenue $281 billion over ten years, on a static basis. In that same year, the Tax Foundation estimated that the ten-year static cost of permanent bonus depreciation would be $336 billion. Furthermore, the current version of the Tax Foundation model finds a significantly larger cost to permanent bonus depreciation than it did in 2015 (following updates that more accurately accounted for the transitional effects of depreciation changes).

As a result, there is good reason to believe that the JCT’s model may estimate a significantly lower fiscal cost from full expensing than the Tax Foundation’s model does. It is not entirely clear why this is the case; we suspect that it might have something to do with how our respective models treat business net operating losses. Either way, this is an important consideration for lawmakers, given that the JCT serves as the official arbiter of the fiscal impact of tax legislation.

Full expensing would grow the U.S. economy, making up for some of the revenue loss

The final reason why the cost of full expensing would be less than $2.2 trillion is that this figure is a static estimate, which does not account for any effects of the policy on the U.S. economy. In reality, there is good reason to believe that full expensing would encourage business investment, leading to greater production and a larger tax baseThe tax base is the total amount of income, property, assets, consumption, transactions, or other economic activity subject to taxation by a tax authority. A narrow tax base is non-neutral and inefficient. A broad tax base reduces tax administration costs and allows more revenue to be raised at lower rates. . These economic effects would partially offset the static cost of full expensing.

In the context of the House GOP plan, we estimated that moving to full expensing would cost $2.2 trillion on a static basis, but would also increase U.S. GDP by 5.4 percent. A larger U.S. economy would mean growth in the individual income and payroll tax bases, which would help recoup some of the federal revenue loss. In the context of the House GOP plan, we estimated that the dynamic cost of moving to full expensing would be $883 billion over ten years.

Since last June, we’ve updated our model somewhat, and now find a smaller dynamic effect from full expensing. However, the basic story remains the same: full expensing is one of the most pro-growth tax changes, would greatly encourage business investment, and would cost significantly less than $2.2 trillion on a dynamic basis.

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

Subscribe